Teacher Cheryl Hernandez makes math fun for her ninth-grade Algebra I class at Mater Academy Preparatory High School. Students pass around a stuffed hedgehog while taking turns answering questions during a square root exercise.

KISSIMMEE, Fla. – When it came time to find an elementary school for her daughter Amanda, Maria Jimenez researched several options in Osceola County before choosing Mater Brighton Lakes Academy, a charter school with a strong academic reputation and a vibe that “felt like home.” A friend with a daughter the same age as Amanda chose a different school. But a year later, when the friend saw Amanda and her classmates surging academically, the friend switched to the charter school, too.

“Parents are talking. Parents are comparing,” said Jimenez, a stay-at-home mom. “Parents are doing whatever’s best for their children.”

Booming Osceola County, just south of Orlando, is the latest hot spot for school choice in Florida.

Fueled by Puerto Rican transplants looking for better jobs and a better life, the population of Osceola has rocketed 70% in the past 10 years and more than doubled in the past 20, to nearly 400,000 people. As fate would have it, that search for economic opportunity coincides with Florida’s expansion of educational opportunity.

“Education is very important to the Puerto Rican community,” said Jimenez, who is of Puerto Rican descent and now has two children – Amanda, in fifth grade, and Jayden, in first – attending Mater Brighton Lakes. “Why are they choosing charter schools? Because they challenge students. You can tell the students are learning in a way that’s going to help them through their entire life.”

Osceola now has the highest rate of students in charter schools among the big urban counties in Florida, recently surpassing Miami-Dade. The 25 charter schools in this corner of Florida, once better known for cowboys than Boricuas, enroll more than 15,000 students. That’s 22% of the county’s public school enrollment, and up 41% from five years ago.

Carmen Cangemi, the principal of Mater Brighton Lakes Academy and Mater Academy Preparatory High School, chats with high school students in the cafeteria before class begins. Students and parents alike give the charter schools high marks for safety, academic rigor and responsiveness. At Mater, one student said, “People listened to what I had to say. My voice mattered.”

The trend lines belie the myths. The primary beneficiaries of choice are Black and Hispanic students from working-class families, like those who left Puerto Rico in the wake of the Great Recession and Hurricane Maria. And if choice is an exclusive tool of the political right, as choice opponents often suggest, somebody forgot to tell their parents. In Osceola, one of Florida’s fastest-growing “blue” counties, Democrats now outnumber Republicans 2-to-1.

Hispanic parents are especially enthusiastic about choice.

Florida’s public-school enrollment is 35% Hispanic. Its charter school enrollment is 44% Hispanic.

Hispanic students in Florida also make up a disproportionate share of students using private school choice scholarships and education savings accounts.

In Osceola last year, more than 3,000 Hispanic students used the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income families. More than 350 others used education savings accounts for students with special needs. Those programs are administered by Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that hosts this blog.

Osceola County School Board Member Jon Arguello is not surprised.

Charter schools have helped the district accommodate growth. And relations between the district and charter schools tend to be good, which is not the case everywhere in Florida.

But parents – especially Hispanic parents, Arguello said – also like what they see in charter schools.

“Charter schools have a more diverse workforce and smaller environments which suit Hispanic families,” said Arguello, who supports choice, including non-district options. “Hispanics, culturally, don’t like to complain about educators or medical professionals, they just quietly leave.”

Fifteen charter schools have opened in Osceola in the past 10 years. All around them, pastures and orange groves continue to sprout homes at a wild pace. The new subdivisions with palm-lined entrances are impossible to miss. So are the new churches with Spanish names, and the restaurants selling mofongo and tres leches cake.

Mater Brighton Lakes and three others in the Mater network are among the new schools.

At 12 of those schools, students of color are 75% or more of total enrollment.

At Mater Brighton Lakes, it’s 92%.

The Mater network decided to expand its Brighton Lakes location three years ago, so the same campus is now also home to Mater Academy Preparatory High School. Together, the schools enroll 1,500 students.

Serviced by the charter school support organization Academica, the Mater network has a long track record of academic accomplishment, and long standing among parents as responsive.

“We are smaller. You can make a better connection. And you can have multiple children all in one school, from elementary school to high school,” said Carmen Cangemi, a former teacher in the Miami-Dade school district who is now principal of the two Mater schools. “Parents love that opportunity.”

Many students attended other schools before coming to Mater.

Blanca Pagan, a 10th grader, described her former school as “disorganized,” with pervasive fighting and bullying. Her parents complained, she said, but nothing changed. At Mater, “I didn’t feel left out, and I became more comfortable,” she said. “Academically, it’s amazing.”

Students at Mater Academy Preparatory High school chat before class begins with principal Carmen Cangemi and assistant principal Tyler Moran. Students and parents alike give the charter school high marks for safety, academic rigor and responsiveness.

Naomy Sepulveda, also a 10th grader, said the unruly behavior of other students at her prior school upset her, but she stayed quiet because she didn’t think speaking out would make a difference. Once she got to Mater, “people listened to what I had to say,” she said. “My voice mattered.”

Mater’s high school might be smaller, but it still offers a broad array of advanced classes, electives, sports and clubs, and perhaps, given its size, even more leadership opportunities. For many parents, it’s a winning combination.

Gwyneth Williams transferred her daughter Andrea to Mater in sixth grade.

A contract negotiator for TECO, Williams said she wanted a school with a tight-knit, family atmosphere and high expectations. Now in 11th grade, Andrea has completed multiple dual enrollment courses and is on track to graduate with both a high school diploma and an associate degree.

“The teachers see the potential and the students are rising to it,” Williams said.

Arguello, the school board member, said charter schools have shown what’s possible with a model that’s more flexible and adaptable.

Going forward, he said, the district and charter sector should be partners in developing options that better serve the community.

“Hopefully the competition gets us there,” he said.

Kendrah Underwood, founding principal at IDEA Victory Vinik Campus, embraces a simple but profound philosophy: The proof of an individual's success is the positive impact he or she can have on the lives of others.

In 2019, when she was teaching at Butler College Prep, a public four-year charter high school in Chicago, Kendrah Underwood earned the reputation as the world’s coolest teacher for filming a video of her students rapping about what they were willing to do to earn a good grade.

The video, which attracted 5 million views in less than a week, looks like a well-rehearsed routine. But Underwood says the idea for it came to her a couple of days before filming.

“I'm a creative, think-outside-of-the box educator,” she told the Daily Mail after the video went viral. “I wanted to change the narrative of what the world continues to hear about Black students when it comes to education and positivity.”

Now, the former forensic science teacher has brought her philosophy to IDEA Public Schools, a network of public charter schools that serve more than 75,000 students at 137 locations. One of the newest is IDEA Victory College Prep in Tampa, Florida, where she is founding principal.

Underwood already is doing things in her own inimitable style.

Always looking for ways to inspire her students, Underwood organized a drum line to greet everyone on her school's opening day.

She filmed a school tour this past summer in which she and her lower-school counterpart danced in their offices. On the first day of the new school year, she arranged for a drum line to welcome students as they stepped out of their cars and onto the new campus. (You can watch the video here.)

Underwood, an Atlanta native, is one of six sisters. She learned from her mother, who was a teacher, that “education was the one thing that can never be taken away from you.” Her mother’s “each one, teach one” approach to child rearing taught her “if one of us knew something or learned something, we had to teach our siblings.”

Though Underwood respected her mother’s profession, she did not want to follow in her footsteps.

“I saw how she worked so hard. Education shifted, and it changed. Before it had a lot more respect and prestige, but then it kind of went away from that. So, I had no aspirations of teaching.”

Growing up, Underwood wanted success, which she defined as a certain amount of money, a big, corner office and “just living the dream.” She considered several careers, among them becoming a lawyer.

She attended public district schools before heading to Agnes Scott College, a private, all-female college in metro-Atlanta. She earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology and anthropology and minored in Africana studies. After graduation, she earned a master’s degree in business administration and another in accounting and finance from American Intercontinental University.

Underwood’s first career job was as a sales manager for Cox Communications. She was a huge success and managed 250 auto dealer accounts in 72 cities. But it didn’t feed her soul.

“I found myself spinning my wheels and not living and working in my passion,” she said.

The experience she considers transformative was a church mission trip to Liberia and Ghana, where her group provided health care and helped train educators. She shared what happened on the trip in a presentation for Toastmasters International at Turner Broadcasting, where she worked as an employment paralegal.

It was during that trip that she found her calling to be a teacher.

“I was able to quiet my mind and listen to the purpose God had for my life,” she said.

In 2014, she joined Teach For America, a national nonprofit organization that works in partnership with 350 urban and rural communities across the country to expand educational opportunity for children. As a corps member, Underwood taught STEM to seventh- and eighth graders in Clayton County, Georgia, a southern metro Atlanta suburb.

In a series of videos for her forensic science students at her former school, Underwood encourages them to "follow the DNA" in a parody of a popular song by rapper Cardi B.

Two years later, she headed for Chicago and Butler College Prep, where students are called leaders and a rigorous curriculum is offered that includes martial arts in addition to academics. She established a forensic science program and started creating motivational videos, including a parody of the Cardi B song “Bodak Yellow,” in which she and her students rapped and danced in white lab coats.

After working in traditional district public schools, Underwood says she prefers the freedom of charters, which are publicly funded but privately managed. Like district schools, they are tuition-free.

“I have worked in both, and (traditional district) schools are just different, and that’s all I’m going to say,” she said.

Two years after joining Butler, she was tapped to become an assistant principal at Success Academy, part of a charter school system that serves 23,000 mostly minority students in New York City who are outperforming students from the most affluent schools in the city and the state. She continued making headlines and using her famous videos as a teaching tool there.

Last year, when IDEA Public Schools announced plans to build two new campuses in Tampa, Underwood was tapped as principal in residence for Victory College Prep a full year before the campus opened in August.

She and Latoya McGhee, principal of IDEA’s Victory Academy, which serves elementary students, worked together to oversee the opening of the new school, one of Florida’s Schools of Hope, incentivized to locate near persistently low-performing district schools as an alternative for families seeking options. The schools promote a culture of “rigor and joy” and cite a 100% college acceptance rate in making their case to parents.

That same year, Underwood turned 40 and received her doctorate in education from Grand Canyon University in Arizona. The degree earned Underwood the nickname her colleagues and students use: “Dr. K.”

Underwood, who is mother to a middle school-aged son, says her experience as a parent has helped her be successful as an administrator because she can relate to families. The fact that she is doing what she feels she was called to do equips her to work long hours and deal with challenges that come up each day.

“If you are in your passion, it’s not work,” said Underwood, who credits her ability to do it all to “Black Woman Magic.”

Underwood might not have the corporate corner office or the big salary that comes with it, but she’s living the dream as Dr. K.

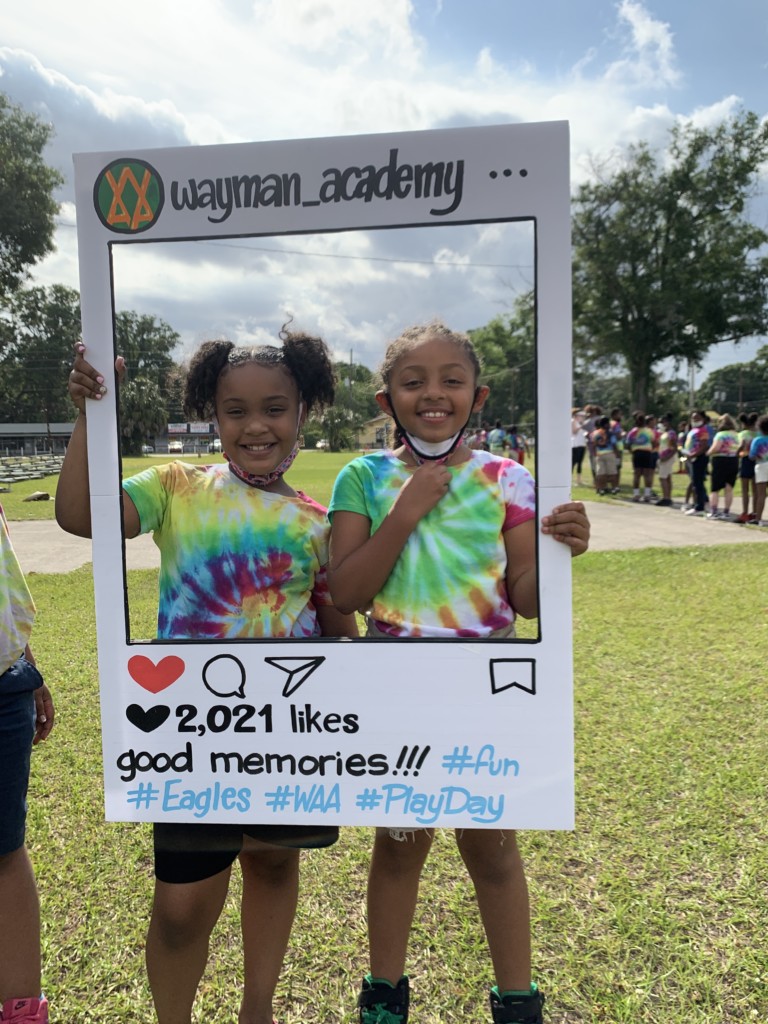

Wayman Academy of the Arts, founded in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1999, was approved as one of Duval County’s first charter schools. The academy’s vision is to provide a learning environment that is innovative, challenging and nurturing through exposure to the fine arts.

Editor’s note: This opinion piece from the Rev. Mark L. Griffin, chairman of the Wayman Academy of the Arts Board of Directors, appeared Sunday on jacksonville.com.

A recent op-ed column lamented that charter schools in Duval County “are proliferating all over town.” The author should ask herself why that is.

It’s because charters are responding to public demand: Families want them for their children.

Charter schools have become Florida’s most popular school choice option, with nearly 700 charter schools serving 341,000 students – enrollment that has increased 3.6% during the pandemic. Fifty percent of their students are from low-income families (they qualify for free or reduced-price lunches); 63% are Hispanic or Black.

They include the charter school I helped found 20 years ago, Wayman Academy of the Arts, one of the first charters in Duval County. The vast majority of our 250 students are Black and from low-income families; about a third live in the former Eureka Garden development nearby. We also attract students from around the Jacksonville area who are drawn to our rigorous academic curriculum and arts programs.

To continue reading, click here.

University High School in Tucson, Arizona, was ranked No. 17 in the nation and No. 2 in the state in the 2021 U.S. News & World Report analysis of the country's high schools.

In an earlier post, I explained why districts don’t tend to replicate or expand high-demand schools. In a word, the reason is politics.

Adults working in low-demand schools, with enrollment well below the design capacity of their buildings, tend to look upon expanding or replicating high-demand district schools in a way not dissimilar from their all-too-common view of charter schools: somewhere on the fear to loathing spectrum.

School district boards are strongly influenced – one might even say easily captured – by incumbent adult interests. When I wrote my previous post, I gave the example of University High School in the Tucson Unified School District. Tucson Unified once was the largest district in Arizona but has shown a consistent trend of shrinking enrollment for decades despite its location in a rapidly growing state.

University High, a magnet school that is housed in the basement of another high school, has been a fantastically high performing-high demand school with a majority-minority student body for many years. The school earned an “A” grade from the state of Arizona and a 10/10 rating from GreatSchools, which in its equity overview stated that disadvantaged students at this school are performing far better than students elsewhere in the state and that the school successfully is closing the achievement gap.

In a reasonable world, we’d figure out how to provide more Tucson kids with the opportunity to attend University High.

Tucson Unified has an abundance of vacant school space, so in a remotely rational world, University High would have its own space, and there would be multiple University High campuses. (Give the people what the waitlists are telling us that they want!) University High, however, does not operate in a rational system, but rather in an urban school district.

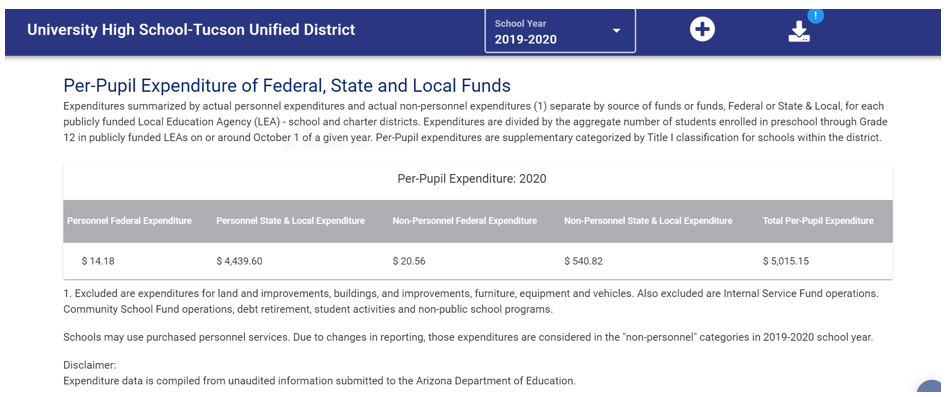

Rather than scaling or replicating University High, the Tucson Unified School District has been systematically starving the school of resources. Tucson Unified spent just under $11,000 per student in 2020 according to the Arizona Auditor General report.

High-schools are more expensive to operate than elementary schools, so we would expect higher spending per pupil in high-schools than elementary and middle schools. Here is the per pupil revenue figure that the TUSD administration reported to the Arizona Department of Education for University High:

So, if you are scoring at home, Tucson Unified has a high demand, high performing school with a waitlist that it keeps in the basement of another school. Self-reported district figures show Tucson Unified provided less than half the per-pupil funding than the district receives on average. It would appear that Tucson Unified is not only keeping University High living under a staircase, it also is keeping it on a financial starvation diet.

Keep this in mind the next time someone attempts to argue that there is “already choice in the district system.” There is some choice in the district system, but organizations don’t often disrupt themselves.

The IDEA Victory campus is one of two state-sanctioned “schools of hope” slated to open this fall in Hillsborough County.

As school board members in one Florida county face state consequences for pushing back on charter school contract renewals, two of the state-sanctioned “schools of hope” are joyously preparing for openings next month in the same region.

IDEA Public Schools is opening its Hope and Victory campuses on Aug. 10 to students in grades K-2 and 6. The schools plan to add grades each year, eventually providing a K-12 education.

“We’re getting ready to welcome our teachers in a couple of weeks,” said Emily Carlisle, one of two founding principals of IDEA Hope, which is opening in a new building at 5050 E. 10th Ave. near Ybor City. “It really feels like school is about to start.”

Carlisle, who heads the Hope college preparatory school, and Latoya McGhee, founding principal of the academy for the lower grades at IDEA Victory-Vinik campus near the intersection of Nebraska and Fowler avenues, have spent months with their respective teams sharing the story and philosophy of IDEA with their communities, where assigned district schools are among 39 countywide the state has classified as “persistently low performing.”

Both principals have partnered with businesses such as ZooTampa at Lowry Park and University Mall as well as the Hilton Embassy Suites to host informational meetings. They also have hosted online giveaways to generate excitement about the school openings.

Carlisle said being the new kid on the block can be challenging, but the IDEA team is willing to do whatever it takes.

“We’ve been organizing and working hard, canvassing door to door,” she said.

Their efforts have paid off, with kindergarten slots filled at the Hope campus. A handful of slots remain for first, second and sixth grades.

“If anyone is looking for an option for their children, we encourage them to check us out,” Carlisle said.

This year marks IDEA’s first foray into Florida. The Texas-based charter network is best known for a program that has resulted in 100% of its students accepted into college. The latest rankings of the most challenging high schools in the nation by the Jay Mathews Challenge Index published in the Washington Post placed all 15 eligible IDEA college preparatory schools in the top 1%.

The company plans to open a school in Jacksonville in 2022 as well as a third campus in Tampa.

Schools of Hope are charter schools that are designated by the state as “high performing schools.” They serve students from “persistently low-performing schools” or within a 5-mile radius of such a school, and students residing in impoverished communities. In addition to IDEA Public Schools, others with the designation include Mater Academy, Democracy Prep Public Schools, Inc., KIPP New Jersey, and Somerset Academy, Inc.

On the Hope campus, homerooms are named after colleges and universities, from Ivy Leagues to historically black colleges and universities and regional colleges to keep the goal front and center for students.

Carlisle describes the experience as full of “rigor and joy” with high expectations set for students from mainly low-income households.

That joy was on full display in a recent Facebook Live “table talk” video done from the Victory-Vinik campus with McGhee, who heads the academy or lower school, and Kendrah Underwood, principal of the college preparatory school.

“I can’t wait til my babies get here!” McGhee said.

The pair shared information on everything from uniforms to after school programs to transportation, which they described as being “like a limo ride to your school.” During a tour of the building, their excitement had them dancing in their offices.

“This building is coming alive,” Underwood said. “Look at the lights, look at the paint, look at the floor. It is smelling and looking and feeling like a brand new, state-of-the-art school.”

A budget adopted last week by lawmakers in Arizona includes two key provisions geared toward expanding access to schools of choice for the state’s K-12 students.

A budget adopted last week by lawmakers in Arizona includes two key provisions geared toward expanding access to schools of choice for the state’s K-12 students.

A $10 million allocation will establish transportation innovation grants that school districts, charter schools, and other community groups can use to help students attend a school that formerly may have been unavailable to them due to a lack of transportation options. In addition to the grants, funding can be used to modernize existing transportation systems.

The budget also makes the school district open enrollment system more transparent.

Both provisions were goals established by education advocates and Arizona Gov. Doug Ducy at the start of the legislative session. As part of his administration’s “Arizona Resilient” policy statements, Ducey urged legislators to remove one of the greatest barriers to accessing school choice, pointing out that “a choice is only a choice if you can get there, and unfortunately, those with the greatest hurdles to getting there are in our low-income neighborhoods.”

The transportation plan earned bipartisan support before it became part of the overall budget package and garnered the attention of parent advocates who testified to the House Ways and Means Committee about challenges they face under the current school transportation system.

In a column that appeared in the Arizona Capitol Times, Querida Walker, a parent of five, noted that her appearance before the committee, rather than serving as an opportunity for her to lead the way to new programs and solutions to help families, resulted in criticism “by individuals and policymakers who are content with maintaining the status quo and keeping kids trapped in failing schools.”

Arizona’s current open enrollment policy, which has existed in Arizona for decades, allows students to attend public schools other than the campus for which they are zoned based on their address. But education choice advocates have charged that some districts discourage the use of open enrollment school choice by shielding information about enrollment windows or by creating opaque paperwork requirements.

Ducey pledged to end what he called exclusionary policies such as unreasonably short enrollment windows that he said cause hardships for parents.

“The way we do open enrollment at school districts across the state is overdue for reform,” Ducey said. “It’s time to make it truly open for all.”

Emily Anne Gullickson, president of Great Leaders, Strong Schools, a group that advocates for increasing students’ access to high-quality schools, praised the measures as a means of ensuring all families will have equitable access to education choice.

“With the passage of this budget, Arizona is making it clear that families choose public schools they wish to attend,” Gullickson said. “Public schools no longer get to pick the students they serve.”

Cameron Frazier will bring his charter school experience to Becoming Academy, scheduled to open this fall in North Florida, which he modeled on the historically Black colleges and universities concept.

Cameron Frazier didn’t attend a historically Black college or university, but the veteran educator recognizes their power, thanks to one of his former bosses.

“During my work in Nashville, my principal was an HBCU graduate, and she was the poster child for HBCUs,” said Frazier a first-generation college graduate who earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of North Florida and a master’s in educational leadership and administration from Lehigh University. “She said they produce the most Black doctors, Black lawyers and the most Black professionals.”

That’s why Frazier is using the HBCU model to prepare the youngest learners in his north Jacksonville, Florida, community for admission to these high-profile colleges, whose graduates include Martin Luther King Jr. and Vice President Kamala Harris.

Becoming Collegiate Academy, which is slated to open this fall, is among the growing number of Black-owned schools opening across the nation as more states adopt education policies that allow greater parental choice.

“My inspiration kept coming back to HBCUs. I knew that was where excellence lies,” he said.

Frazier, 31 joined the Teach for America Corps in 2012 and spent three years teaching English at a district middle school before moving from Jacksonville to Nashville to teach third grade at Rocketship Elementary School, a charter school whose stated vision is to “eliminate the achievement gap in our lifetime.”

From there, he served on the team that brought KIPP charter schools to Nashville and was a founding assistant principal. Those experiences made him want to launch a school of his own aimed at helping to close the achievement gap for students of color. What prompted him to act sooner rather than later was a newspaper story he read about 34 children who had been shot or killed in his Jacksonville community in that one year alone.

“That broke my heart. That brought tears to my eyes,” he said. “That’s when I decided it was time to come home.”

Frazier, who also will serve as the school’s principal, worked with Duval County School District officials to get approval for Becoming Collegiate Academy. He said the authorizers strictly enforced all application rules but were fair as he sought to make his dream a reality.

“They were always very cordial and nice, but they always held the expectations high for me, and they made sure our charter application was exactly what it needed to be,” he said. “They were not going to cut corners, and they shouldn’t. They had high expectations and it was on us to reach them, and ultimately we did, because at the end of the day, we want to make sure we open up great schools for kids.”

Like many other charters, Becoming Collegiate Academy is using a slow-growth model, opening only to kindergarteners this fall, then adding a grade each year until it serves students in kindergarten through fifth grade. Frazier, who expects to start with 54 students, is leasing space at a church in north Jacksonville’s Norwood neighborhood but likely will look for a dedicated building as Becoming Academy expands. He hopes to serve 600 students once all grades are included.

A typical day will start with a personal greeting from staff as students arrive at school. After a schoolwide opening assembly, students will separate into their cohorts, each named in honor of an HBCU, where learning will begin. At both breakfast and lunch, Becoming Academy will participate in the federal school breakfast and lunch program.

Frazier, who is especially concerned with raising state reading scores, will devote twice the amount of time that school districts do, which is usually 90 minutes, to literacy instruction.

A study by 904orward.org, a nonprofit group that promotes diversity in Jacksonville, cited Florida Department of Education figures from the 2018-19 school year showing only 37% of Duval County third-graders passed Florida’s standardized English and language arts test compared with 45% of Hispanic students, 66% of white students and 74% of Asian students.

“An overwhelming number of Black kids are not reading on grade level,” Frazier said, describing the situation as “atrocious.”

Becoming Academy is an independent charter school as opposed to being part of a national network such as IDEA Public Schools or KIPP. Its board of directors include Audrieanna Burgin, a research scientist at Zearn, a nonprofit publisher of math curriculum, as well as an attorney, architect, engineer, and staffer for U.S. Rep. Al Lawson Jr., whose district covers a large swath of north Florida.

Frazier plans to draw on his experience KIPP and other schools to create the best environment to educate and empower children. The key to closing the achievement gap, he said, is to start as early as pre-school and kindergarten, which frequently is overlooked in many schools, where minority children are not expected to perform well – and are not celebrated when they do.

“They think, ‘I don’t feel like I’m smart. I don’t feel like I’m learning. I don’t get the things I need to be successful,’” he said. “I need to immerse them in the experience that is the HBCU culture so our kids can experience that as early as kindergarten and not have to wait until college. Education is the ultimate civil right of our generation.”

Starting with a single charter school in Miami in 1996, the charter school movement has gained momentum in Florida and is now the state's most popular school choice option, with nearly 700 charter schools serving 330,000 students.

Editor’s note: Today’s commentary comes from Nina Rees, president and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, the leading national nonprofit organization committed to advancing the charter school movement.

Nina Rees

In 1991, Amazon and Google didn’t exist. Neither did smart phones. The internet was a fledgling idea, and a small band of teachers and school leaders in Minnesota were about to change America’s education landscape forever.

The state passed the first charter school law in the country, creating a new type of public school independent of the school district, focused on the individual needs and interests of students and propelling them to academic success. With the law’s passage, Minnesota became the model for flexible, student-centered, innovative public education options.

Fast forward 30 years to today, and 44 states have public charter school laws serving 3.3 million students. Nearly 220,000 dedicated teachers deliver education at 7,500 charter schools. Now that’s something to celebrate.

This month, National Charter Schools Week 2021 was a time to reflect on those 30 years of work to close the opportunity gap and deliver an excellent education to every student. The innovation that charter schools bring to education lies within the built-in flexibility and autonomy to design and implement classroom instruction. Simply put, teachers and leaders have the freedom to do whatever it takes. They can meet students where they are and provide the best learning methods for them to gain the knowledge and skills needed to be successful in college, career and life.

That model works. Millions of students and thousands of teachers and schools make up the dynamic charter school community. Some schools focus on college prep, some follow a STEM curriculum, and others integrate the arts into each subject. All are focused on students and their unique learning needs.

Again this year, U.S. News & World Report released the 2021 Best High Schools ranking which included data on nearly 24,000 public high schools. And once again, charter schools outperformed. Charter schools made up 10% of public schools in the ranking, but they made up 24% of the top 100 best high schools.

Charter schools in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, North Carolina and Texas were represented on the top 100.

Charter schools overwhelmingly serve underserved students: urban students and those who are Black, Latino or come from low-income families. And they do it exceptionally well. Students in urban charter schools gained 40 additional days of learning in math and 28 additional days of learning in reading per year as compared to their district school peers. Low-income Hispanic students gained 48 additional days in math and 25 additional days in reading, while low-income Black students gained 44 additional days in reading and 59 additional days in math per year.

And four or more years of enrollment in an urban charter school led to 108 additional days of learning in math and 72 additional days of learning in reading per year.

While it is important to look back at how far charter schools have come in three decades, it is even more important to look ahead. The pandemic has shown us that now more than ever, American families want more high-quality public education options.

Education is not a fixed place, a person, or a system – it is a right. Charter schools are a critical part of public education, and our movement to bring better options to more families who need it is growing. New schools are opening and enrollment is increasing, signaling that parents and communities want and need the educational options that charter schools provide.

Charter schools are born out of a community need for more and better, with passionate educators and parents who are committed to giving more kids the opportunity to have a great education, taking up the mantle and making it a reality. It is common to see charter schools led by former teachers who wanted to take the lessons they learned in the classroom and apply those lessons to an entire school. And that’s the beauty of the chartering model.

Charter schools across the country have the strong support of their local communities and people across the political spectrum. In Florida, the Legislature this year passed a law allowing Florida’s colleges and universities to issue charters, making the process easier, but not less accountable, to start and expand charter schools. This will lead to more education options and learning opportunities for Florida students.

What started with one law and one school in Minnesota has blossomed into a nationwide movement.

Student-centered, tuition-free, and always public, charter schools have changed the American public education landscape for the better. The celebration this month of National Charter Schools Week has been a time for everyone to highlight and celebrate the schools, students, education leaders and advocates that have demonstrated the strength and promise of the charter school movement over the last 30 years.

Orlando Science School in Orlando, one of nearly 700 charter schools in Florida, focuses on science, technology, engineering and mathematics and is ‘home base’ for more than 1,000 Central Florida students representing diverse cultural and economic backgrounds.

The charter school movement in Florida started with a single school in Miami in 1996. Now it’s Florida’s most popular school choice option, with nearly 700 charter schools serving 330,000 students.

At the quarter century mark, Florida’s charter school sector continues to generate new fans among parents, including … me. ????

Here’s 25 reasons why, in no particular order …

1. T. Willard Fair. If movements are judged by the company they keep, then it’s worth noting charter schools are backed by a who’s who of icons. Trail blazing and fiercely independent, Fair, the head of the Urban League of Greater Miami, co-founded that first charter school with …

2. Jeb Bush. Expanding parental choice and learning options, including charter schools, was/is vital to Gov. Bush’s vision. The Republican governor got a little help from …

3. Lawton Chiles, his Democratic predecessor. “Walkin’ Lawton” signed the charter school bill into law in May 1996, after it passed the Legislature with huge bipartisan support.

4. Rosa Parks. No direct Florida tie. But if you find anybody still clinging to “charter schools are a right-wing thing,” please let them know the First Lady of Civil Rights tried to start one.

5. Barack Obama. He liked charter schools so much, he vowed to double federal funding for them.

6. Bill Clinton. A “mistake,” he said in Orlando, for districts to keep fighting charters.

7. Rainbow coalition. Florida charter school students are 50% low-income, 63% Black or Hispanic.

8. Survey says. Parents of color are especially appreciative.

9. National model. Laws governing Florida charters are among the best in America. The best part is Florida charters are especially …

10. Accountable. The pitch from Matt Ladner: Parents don’t play.

11. Healthy competition. The best available evidence shows charters don’t hurt traditional public schools, probably help them, and probably help more as their numbers grow.

12. Let 1,000 flowers bloom. Here, here, here, here, here, here …

13. Black minds matter. Here’s but one good example.

14. Teacher power. Last I checked, Florida charters employed 14,000 teachers, more than nine states have teachers. (Hopefully we’ll have current data soon.) They appreciate the freedom.

15. They’re everywhere. If you’re near this gem of a charter in flyover country, don’t veer off U.S. 98 until you get a soft-shell crab sandwich.

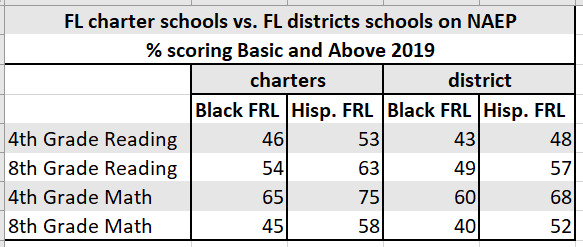

16. Better outcomes. Students in Florida charters typically outperform district students on state and national tests. As but one example, see this chart showing NAEP results for low-income Black and Hispanic students.

17. Better yet. Charter school students in Florida are more likely than their district peers to graduate from high school, persist in college and earn more money.

17. Better yet. Charter school students in Florida are more likely than their district peers to graduate from high school, persist in college and earn more money.

18. Better grades. 74% of Florida charter schools earned As or Bs from the state. 61% of traditional public schools did.

19. Better rankings. Seven of the Top 30 high schools in Florida are charters, according to U.S. News.

20. Academica. Five of those seven are managed by Academica, the best charter org you’ve never heard of (but a key part of the cool story that is choice-rich Miami-Dade.)

21. Science! Charters like this one are killing it.

22. Rigor. Even in the pandemic.

23. Bang for the buck. Florida taxpayers spend 69 cents on the dollar on charter students versus district students. And for those district schools, there’s …

24. No drain. According to fresh research from a charter skeptic.

25. Rising tide. Charters are a big part of the big picture in Florida, which is more choice, better outcomes.

Icing on top …

My kid. My oldest began attending a charter school last fall. He’s thrilled he had options.

So are his parents. ????

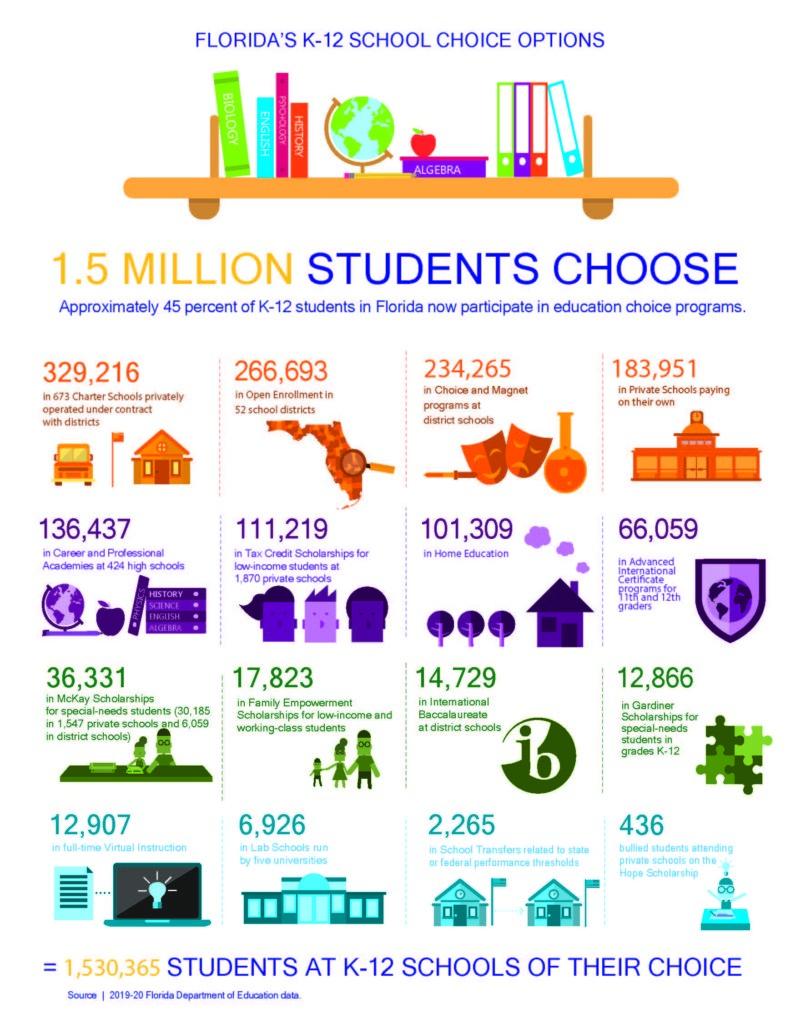

The 11th National School Choice Week celebration kicked off Monday as various organizations, schools, parents and students celebrate educational opportunities in their own unique way. RedefinED celebrates School Choice Week by releasing its 12th annual Florida Changing Landscapes document.

The 11th National School Choice Week celebration kicked off Monday as various organizations, schools, parents and students celebrate educational opportunities in their own unique way. RedefinED celebrates School Choice Week by releasing its 12th annual Florida Changing Landscapes document.

This most recent document, created from Florida Department of Education data, reveals that more than 1.5 million K-12 Florida students participated in school choice during the 2019-20 school year.

This year’s Changing Landscape is a little different than past years. Last year, we saw nearly 1.7 million PK-12 students participating in some form of school choice in the Sunshine State. A detailed breakdown of Florida’s VPK program enrollment, the state’s largest voucher program with around 171,000 students, wasn’t available at the time of publication.

This year, we examined only K-12 school choice programs. Where applicable, such as with private school-private pay or the Gardiner Scholarship, pre-K students have been removed from the count. Likewise, Gardiner Scholarship students who are enrolled in home education programs have been removed from the home education count.

As was the case last year, charter schools dominate the top spot with 329,216 students enrolled. Various public school options, such as magnet schools, career and professional academies and open enrollment continue to dominate the landscape. School choice programs offered by public school districts enrolled more than 717,000 students last year, which means there are more students enrolled in public school choice programs than there are public school students in 24 other states.

Overall, growth in school choice was modest in the 2019-20 school year, adding just 25,000 students for 0.9% growth over the prior year.

The Gardiner Scholarship program, administered by Step Up for Students, the nonprofit that hosts this blog, grew by 17%. Virtual education grew by 15% and Advanced International Certificate of Education programs grew by 14%.

Home education proved to be another popular option, exceeding 101,000 students, a growth of nearly 11% over the prior year.

Career and Professional Academies and Choice and Magnet Programs saw enrollment decline by 6% and 5%, respectively. Private pay students attending private schools shrunk by 3.5%. But thanks in large measure to Florida’s scholarship programs, total K-12 enrollment in Florida’s private schools grew by 5%.

The 2019-20 school year ended amidst a global pandemic that shook public education well into the new year. Nationally, both charter school and private school enrollment grew by 3% while home education grew by 2%.

You can view last year’s Florida Changing Landscapes document here.