Those defending discrimination in education received a well-deserved comeuppance last month—from two quarters. The first, a lesson in constitutional law, matches nicely with the second, the creation of expansive opportunities for parents to choose how and where their children learn.

Those defending discrimination in education received a well-deserved comeuppance last month—from two quarters. The first, a lesson in constitutional law, matches nicely with the second, the creation of expansive opportunities for parents to choose how and where their children learn.

This combination will define K-12 education for the next century.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Carson v. Makin was the first blow to prejudice, this time against religious discrimination. The Court ruled in favor of Maine parents who have no assigned public school in their local areas and so chose religious schools for their children—presenting a challenge for special interest groups who oppose school choice.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote, “Maine’s decision to continue excluding religious schools from its tuition-assistance program … promotes stricter separation of church and state than the Federal Constitution requires.” Again, these Maine students did not have assigned traditional schools to attend nearby. So if parents freely choose a certain private religious school, this does not violate the Constitution.

A teacher union’s response to the decision falls flat: “The power and purpose of public schooling is to educate every child, regardless of geography or demography,” wrote the American Federation of Teachers’ president Randi Weingarten.

But this “power and purpose” clearly did not extend to some rural areas of Maine—the very restrictions Weingarten says public schools are designed to overcome. In Carson, it is private schools that overcame the challenges posed by geography and demography.

Weingarten says the decision “discriminates” against “our most vulnerable students,” hoping we will forget that the children in this case had no assigned public school, making them vulnerable to not receiving an education at all—thus being discriminated against for their geography—had religious schools not been an option.

The second strike against education discrimination came in Arizona.

At the very end of the legislative session, state officials expanded the nation’s oldest education savings accounts to include all students in the state. Arizona’s accounts opened in 2011 and served 75 children with special needs. Over the last decade, lawmakers expanded the accounts to include children from different walks of life, including students on tribal lands, adopted children, children in military families, and children assigned to failing public schools, among other student categories.

In this way, the accounts allowed private education providers, including religious schools, to help those Arizona students that traditional schools could not reach due to geography, demography, or another area of discrimination that the “power and purpose” of assigned schools failed to reach: The soft bigotry of low expectations from persistently low-performing public schools.

The accounts inspired lawmakers in nine other states to adopt similar account options serving thousands of children, including more than 17,000 children in Florida.

In recent years, state lawmakers have been creating learning options that break down barriers between children and families from different backgrounds, income levels, and religions. Florida officials combined the state’s accounts and a scholarship program, securing it in the state funding formula.

West Virginia lawmakers will allow nearly every child in the state to apply to access education savings accounts in the fall. Policymakers in Missouri and Kentucky combined tax credit scholarships with education savings accounts, a unique combination of charitable contributions to scholarship organizations that will allow students to customize an education according to his or her needs.

These learning options have appropriately set high expectations for the future. Small steps may not be noticed, nor impactful. Policymakers in Georgia, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas have come close in recent years and supportive lawmakers should receive applause for their intent. But “coming close” only merited mention when nearly all other states could only reach that far.

Now state lawmakers have gone beyond close, beyond pilot programs with temporary funding. Mindful of parent and taxpayers’ new expectations for state lawmakers, Texas Gov. Greg Abbot said recently, “We can fully fund public schools while also giving parents a choice about which school is right for their child.”

He added, “Empowering parents means giving them the choice to send their children to any public school, charter school or private school with state funding following the student.”

Education savings accounts are the norm. Unions are left defending assigned schools’ limited—discriminatory, even—reach. The future will not be defined by “coming close” to creating quality learning options for all children any more.

Michael Bindas, senior attorney for the Institute for Justice, said a former Maine attorney general did not pay close attention to the Supreme Court’s commitment to religious liberty in recent years, which “embroiled the state in five lawsuits spanning three decades and that culminated in the Supreme Court’s ruling against the state,” and that the state’s current attorney general “seems to not have learned any lessons from that experience.”

Editor’s note: This article appeared last week on washingtontimes.com.

Religious schools got what they wanted when the Supreme Court allowed them to participate in a state tuition program. But the state attorney general said the ruling will be for naught unless the schools are willing to abide by the same antidiscrimination law as other private schools that participate in the program.

An attorney for the families criticized the “knee-jerk” comments, and the leader of a religious group predicted further litigation.

The Supreme Court ruled that Maine can’t exclude religious schools from a program that offers tuition for private education in towns that don’t have public schools. But religious schools didn’t have long to savor their victory before learning of a new hurdle.

Attorney General Aaron Frey said both Christian schools involved in the lawsuit have policies that discriminate against students and staff on a basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, preventing their participation in the tuition program despite the hard-fought litigation.

“The education provided by the schools at issue here is inimical to a public education. They promote a single religion to the exclusion of all others, refuse to admit gay and transgender children, and openly discriminate in hiring teachers and staff,” he said in a statement.

There was no immediate comment from two schools, Temple Academy in Waterville or Bangor Christian Schools.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: Good news for Catholic schools comes on the heels of National Catholic Schools Week, with dioceses including the Archdiocese of Miami posting enrollment gains. This article first appeared on catholicnewsagency.com and uses information included in a recent reimaginED post, which you can read here.

Editor’s note: Good news for Catholic schools comes on the heels of National Catholic Schools Week, with dioceses including the Archdiocese of Miami posting enrollment gains. This article first appeared on catholicnewsagency.com and uses information included in a recent reimaginED post, which you can read here.

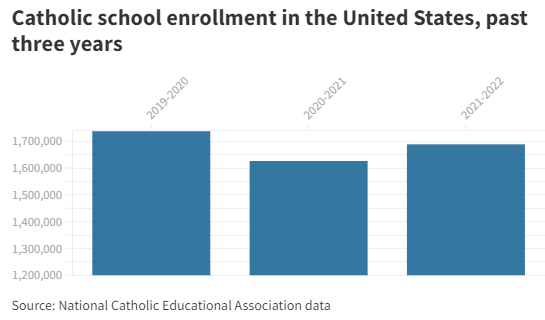

After a difficult 2020-21 year for many Catholic schools, enrollment numbers are rebounding nationwide, according to data from the National Catholic Educational Association.

Overall, enrollment in Catholic schools in the U.S. is up from 1.63 million last year to 1.69 million this year, an increase of more than 3.5%, according to the NCEA. Despite the increase, enrollment numbers do not appear to have yet reached 2019 levels, which saw 1.74 million students enrolled.

Catholic News Agency contacted the 10 largest dioceses in the country by Catholic school enrollment to ask how their enrollment numbers this year compare with last year.

Cincinnati

Cincinnati has a disproportionately large number of Catholic school students for its size. Spokeswoman Jennifer Schack told CNA that the archdiocese has 39,839 students enrolled this year, an increase of 1.5% over the previous year.

However, when looking at the past five years, the number of students is trending down by 2.5%, she said.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Melodie Wyttenbach, executive director of the Roche Center for Catholic Education at Boston College, and Hosffman Ospino, an associate professor of Hispanic ministry and religious education at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry, appeared earlier this week on americamagazine.com. reimaginED is republishing it in honor of National Catholic Schools Week.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Melodie Wyttenbach, executive director of the Roche Center for Catholic Education at Boston College, and Hosffman Ospino, an associate professor of Hispanic ministry and religious education at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry, appeared earlier this week on americamagazine.com. reimaginED is republishing it in honor of National Catholic Schools Week.

Many Hispanic families in the United States make countless sacrifices every year to send their children to Catholic schools. It is not always easy.

It is clear that the rising cost of a Catholic education is a significant barrier to Hispanic enrollment. Less quantifiable is the degree to which Hispanics feel that they are not part of Catholic schools, that they do not see themselves or their cultural traditions reflected in the personnel and curriculum at these institutions.

Major efforts have been made in recent years to address these challenges, including an expansion of bilingual schools, parental choice programs, financial aid scholarships, and madrina/padrina programs, which pair new families with mentor families.

Hispanic teachers and leaders may hold the key to address the third challenge, making Catholic schools more welcoming and embracing educational spaces for Hispanic children and their families. This is one of the major conclusions in the just released Boston College report “Cultivating Talent”, for which we served as the principal investigators.

In 2016, the National Catholic Education Association reported that Hispanics made up 7% of all faculty members in Catholic schools, including full-time and part-time teachers and leaders. That percentage had increased to only 9% in the academic year 2020-21.

There are about 14,600 Hispanic teachers and leaders serving in Catholic schools throughout the country. These numbers are growing steadily and, as they do, so does the impact of these educators upon the life of these schools.

Hispanic educators sustain and expand the mission of Catholic schools in our country in critically distinct and transformative ways. They are gente puente (“bridge builders”), leveraging bilingualism and biculturalism to strengthen schools, faith communities and the larger society. They are anchors within their schools, contributing deeply to the shared cultural, religious and intellectual wisdom that enriches students, families and their colleagues. Through their work within and around Catholic schools, they share in a common desire for justice, inclusion, affirmation and expansion of opportunity for their students.

Inspired by the more than 300 Hispanic educators in Catholic schools who lent their voices to our study, we believe that representation truly matters. We built on research that shows Hispanic students benefit greatly from learning and growing with teachers and leaders who share their cultural and ethnic/racial heritage. That is true of Hispanic students in public, charter, Catholic and other private schools.

A Hispanic teacher shared this anecdote with us:

I remember clearly, when I started as a director, one family came ... a very humble family. And the lady was like, ‘So you’re Hispanic?’ I said yes. She didn’t know how to read or write ... and she was like, ‘You’re the director? ... You speak my language?’ She was pretty much in shock. And then she looked at the little girl and said, ‘One day, you’re going to be like her ...’ I had to hold my tears.

Many other Hispanic educators who participated in this study shared how conscious they are that their presence in Catholic schools means something special for children and families of Hispanic backgrounds. They embody possibility for members of a community that regularly hears negative messages about their culture, traditions and their very identity from various corners of our society.

Hispanic educators in Catholic schools see themselves called to teach all students and to partner with all colleagues to advance the mission of these institutions. Their presence in Catholic schools is a win-win for everyone. They excel as educators and are sources of inspiration for students and colleagues.

Also, about 40% of Hispanic teachers and 27% of Hispanic school leaders in Catholic schools in our study are foreign-born. That means they have the potential to educate all children in our Catholic schools with a distinct international perspective while serving as cultural mediators for immigrant children, families and colleagues.

Another finding from our study is that about two-thirds of Hispanic educators in Catholic schools attended a Catholic school at some point before college, and nearly half of that group told us that their own background influenced their decision to work in a Catholic school.

This corroborates the belief that a firsthand experience in Catholic schooling can significantly influence a commitment to Catholic education. And it is one more reason why we as a Catholic community need to continue to welcome and support Hispanic children in Catholic schools. Doing so is an investment in their future and in the future of our schools.

The Hispanic educators in our national study shared a strong sense of being called to teach in Catholic schools, build a better world and make a difference for others. Practically all (98% of respondents) felt that being an educator in Catholic schools allowed them to contribute to the common good.

There is no doubt that this sense of vocation is grounded in their faith. Indeed, an extraordinary 85% said they attend church regularly. This finding not only reveals a strong sense of Christian discipleship but also shows an enormous potential for engaging these educators in collaborative evangelizing efforts beyond the context of school.

So, there is much to celebrate about the presence of Hispanic educators in Catholic schools. Their numbers are growing, and our study confirms that their presence is a true sign of hope.

As we advanced our research, however, we discovered a trend that should be a red flag for Catholic schools during the pandemic.

The highest number of Hispanic students enrolled in Catholic schools in a given year was reported during the academic year 2017-18, with 319,650 Hispanic students. Yet, there has been a significant decline of 25,000 Hispanic students in Catholic schools since 2018. In general, Catholic schools began recovering enrollment after the pandemic in 2021. Currently, 294,947 school-age Hispanic children attend Catholic schools.

This sets us back to a level of Hispanic student enrollment similar to that of a decade ago. While we agree with those who have noted the pandemic has brought an unprecedented enrollment opportunity for Catholic schools as they have remained open during the most difficult of times, we must ask for whom are these doors open?

Advocacy to support Hispanic teachers in Catholic schools goes hand in hand with advocacy to welcome and support Hispanic children and their families.

Hispanic educators bring powerful, essential, and necessary voices and gifts that are essential to sustain the mission of Catholic schools in the United States. We must support them and create pathways that lead more educators like them to dedicate their lives to these school communities.

During this Catholic Schools Week, let us again embrace diversity in our church as a gift.

Students at North Tampa Christian Academy, the newest school in the Florida Conference of Seventh-day Adventists family, enjoy an immersive on-campus experience that encourages innovation through project-based learning.

“The greatest gift that any educator can give to their students is to serve them by being a foundation for learning rather than a ceiling.” – Frank Runnels

As the organizational body of the Seventh-day Adventist Church for the state of Florida, the Florida Conference of Seventh-day Adventists has a simple but profound mission: to walk together in faith, hope and love. The nonprofit, based in Altamonte Springs, Florida, serves as the administrative body for 280 churches, companies and mission groups, as well as a system of 30 K-12 schools with more than 4,600 students.

Serving as vice president for education and superintendent of schools for the Adventist Florida Conference of Seventh-day Adventists is Frank Runnels, who in his tenure has been a teacher, a boys’ dean, an evangelist, a missionary and a businessman.

reimaginED interviewed Runnels to learn more about how Adventist education differs from other approaches, the value of STEM education, and the role private school scholarships play in supporting students and families.

Q. Tell me a little about the Adventist K-12 system. How many schools do you oversee, and how many students are enrolled?

A. The Adventist K-12 system in Florida is a birth through the 12th-grade program that is part of a larger organization called the North American Division, which oversees about 1,000 elementary and secondary schools and 13 colleges and universities in North America. In addition to overseeing 30 elementary and secondary schools, our Florida Conference Department of Education is responsible for 13 early childhood programs.

Q. What does an Adventist education look like? How is it different from public schools? Are the schools open to non-Adventists, and what is done to make that experience equally relevant to them?

A. Adventist Education focuses on student development aspects that aren't as prevalent or relevant in many other national school programs. Our intentional emphasis on character development through Biblical and social-emotional learning, in addition to academic and extracurricular activities, helps us work toward developing the whole child. We want our students to become outstanding citizens in their communities and be great students in our schools.

Adventist education means enabling students to develop a faith relationship with Christ, supporting their goals and growing their world view. Jesus is a crucial factor in significant learning. From an Adventist perspective, Jesus is the center of all knowledge and wisdom.

Our schools are open and welcome those who are not of our faith. Several of our schools have a higher ratio of children that are not specifically part of our denomination. We believe that every child has the right to reach their God-given potential, and as such, we seek to develop learners that can discover and find value not only in who they are but in who they can become. With all students, our goal is to be intentional in providing a holistic approach to learning.

Q. How important are scholarships to your families? What percentage of students are on a state scholarship, and what is the breakdown? What percentage of these are Florida Tax Credit Scholarships, Family Empowerment Scholarships, or Hope Scholarships?

A. The scholarship program is an essential partner for our families who want a choice in their children's education. We feel so blessed to be in Florida and in partnership with Step Up For Students, which allows students to attend our schools and reap the benefits of private education. About 51% of our students are on some form of scholarship program provided through tax credits.

Q. I see that you have placed a heavy emphasis on STEM education. What have you done regarding STEM lately, and do you have any plans to expand it further?

A. Our innovation and technology initiatives are inspiring and will serve as a pathway and foundation that will strengthen many of our future strategies. While the STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) and design thinking processes inherently push students to use higher order thinking skills, we aim to develop and apply the same strategies and approaches across all subjects and disciplines.

Through our Florida Conference Innovation Lab, many students have been able to patent and produce products that improve many lives. We continue to work toward funding to begin renovations for a new innovation lab to allow for creativity and vision. We are looking to build a teacher training facility designed to help teachers develop their project-based learning applications and innovation thought abilities. This lab will be open to the public and will serve as a sector of influence in the community and our schools in Florida.

Q: What drives your passion for education?

A: My passion stems from my faith, values, and a clear understanding of God’s calling and purpose. I am convinced that God has placed within every child the capacity to learn, grow, and do marvelous things. Our responsibility is to provide opportunities, teaching, guidance, and stimulating environments that challenge our students' thinking and lead them to discover their passion and God’s purpose for their lives.

The greatest gift that any educator can give to their students is to serve them by being a foundation for learning rather than a ceiling. Believing this, we want our students to dream and imagine great possibilities, seize opportunities, succeed through failure, and strive toward their potential and goals. We want to give them the opportunities to expand beyond the confines and norms of traditional education paradigms and learning structures. I believe that this is the learning system that God has always intended and is leading us back to: "Greater than the highest human thought."

Q. What is your vision for the future of Adventist education?

A. I see the Adventist education system fulfilling its purpose in North America when it becomes the desired destination for learning and growth. At this time, we have not arrived fully, as we still have pockets of excellence throughout our systems. However, I confidently look forward to the time, and it's coming very soon, when equal access and learning opportunities create greater possibilities of development for every student. Currently, the Florida Conference Office of Education has begun a journey to systemize those values through a three-tier initiative of innovation, development, and systemic planning.

I see Adventist education better addressing mental health issues and social and emotional learning, which teaches students to manage emotions, set goals, show empathy for others, maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.

Our kids will learn to be advocates through our teaching philosophy, not only for their faith but also for societal issues, justice, and social causes. They are no longer sitting on the sidelines waiting for someone else to lead but working as contributing citizens in corporate America, their churches, and their communities. Our students must be taught and understand their commitment to the Lord and their responsibility to something greater than themselves. With that mindset, students can find joy and fulfillment and will then truly impact the world for good.

Q. According to your website, North Tampa Christian Academy is the latest new school. What are the plans to expand your footprint in Florida?

A. We want to build another school of Innovation in Broward County. We are currently looking for existing properties to accomplish this vision. We see North Tampa Christian Academy as the beginning of what can be, believing that the best is yet to come.

Editor’s note: National Catholic Schools Week, celebrated this year as Celebrate Catholic Schools Week from Jan. 31 to Feb. 6, is an annual celebration of Catholic education in the United States. In today’s post, Michael Barrett, Associate for Education for the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, explains why, in his view, Catholic schools remain an excellent school choice option for families.

Editor’s note: National Catholic Schools Week, celebrated this year as Celebrate Catholic Schools Week from Jan. 31 to Feb. 6, is an annual celebration of Catholic education in the United States. In today’s post, Michael Barrett, Associate for Education for the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, explains why, in his view, Catholic schools remain an excellent school choice option for families.

For years, the Catholic Church has promoted school choice and has advocated for the right of parents to choose the educational option that best suits the needs of their child. Today, Florida is on the cutting edge when it comes to providing families with real educational options. But among these options, what sets Catholic schools apart?

For years, the Catholic Church has promoted school choice and has advocated for the right of parents to choose the educational option that best suits the needs of their child. Today, Florida is on the cutting edge when it comes to providing families with real educational options. But among these options, what sets Catholic schools apart?

I would like to highlight two aspects of Catholic education. The first is community.

One of the most striking aspects of an excellent Catholic education is authentic community – not merely a community of students and teachers effectively receiving and imparting knowledge, but a network of families and individuals who know and care for one another deeply.

While this community begins at school, it is not limited to regular school hours or confined to the school building.

Growing up in Brandon, Florida, I remember experiencing this in my own Catholic grade school. I recall a real sense of sharing life with other families from my school. My friends and I not only attended the same school; we sat next to each other at Sunday mass and we carpooled together to school sporting events. Our moms served lunch in the cafeteria and our dads worked the food and drink tents at the annual school fair.

Our families ate dinner together, attended parties together, and supported one another through various triumphs and tragedies. By attending Catholic school, our families became immersed in a particular Catholic school community.

Both Catholics and non-Catholics alike have encountered and have been enriched by this distinctive experience of Catholic school community. And indeed, this is by design.

As Archbishop J. Michael Miller, secretary for the Vatican’s Congregation for Catholic Education, has stated, Catholic grade schools should “try to create a community school climate that reproduces, as far as possible, the warm and intimate atmosphere of family life … This means that all involved should develop a real willingness to collaborate among themselves. Teachers … together with parents and trustees, should work together as a team for the school’s common good and their right to be involved in its responsibilities.”

Therefore, Catholic schools are called to be communities, not only for students and teachers, but for the entire family.

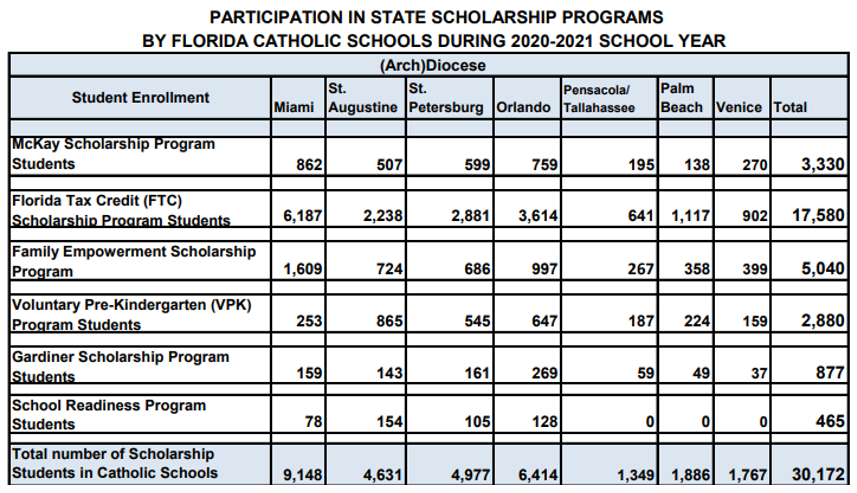

Throughout Florida, 239 Catholic schools serve 79,623 students. Just under 40% of these students participate in one of Florida’s K-12 scholarship programs.

A second aspect of Catholic education is that Catholic school communities are grounded in a particular understanding of human nature and of human love. This understanding of human nature informs and influences the relationships that make up the Catholic school community.

The Catholic Church, and therefore Catholic schools, teach that each and every person has great dignity and worth because he or she is made in the image and likeness of God. Furthermore, Catholic school communities understand love to be a “self-gift,” or charity, best exemplified by Christ’s gift of himself to us on the cross.

This, of course, does not mean that Catholic school communities are perfect. Nor does it mean that every student who walks into a Catholic school must be Catholic. It certainly doesn’t mean that every student must walk out of a Catholic school as a Catholic.

However, it does mean that Catholic schools will be Catholic, and that this particular view of human nature and love will be proposed, taught, and thoughtfully discussed – which, in turn, hopefully will influence and guide the entire school community.

When this is done well, Catholic schools offer distinctive communities and learning environments that exist as a wonderful educational option for Florida’s students and their families.

The critic should not imagine this escapist attitude to be the specialty of the occasional occult and exclusivist faith-based school. Most of us can find it in the mirror.

The American Center for School Choice is committed to the empowerment of all families to choose among schools public and private, secular and religious. As in all programs of government subsidy - food stamps are an example - there will be limits on the product that can be chosen; the school preferred by the parent must meet academic standards and respect civic values. Taxpayers will not subsidize the choice of any curriculum encouraging hatred or violence.

Until the 1950’s public schools could, and did, broadly profess a religious foundation for the good society; and both history and serious contemporary research report the powerful contribution of religious private schools to civic unity. Nevertheless, skeptics of parental school choice for lower-income classes are inclined to worry: are faith-based schools perhaps separatist in their influence simply by teaching - in some transcendental sense - the superiority of believers? The critics’ principal target is an asserted practice of some religious schools to claim a favored access to eternal salvation for their own adherents.

If this allegation is an issue, it is not one for the lawyer; so long as a school teaches children to respect the civil law and their fellow citizens here on earth there could be no concern of the state. It is unimaginable under either the free exercise or establishment clauses of the 1st Amendment (plus the 14th) that government - federal or state - could undertake to censor the content of teaching simply because it includes the idea that the means of eternal salvation are accessible only to some. The State’s domain is this life only, and our governments have so far properly refrained even from asking such an inappropriate question of any school.

The content of religious teaching could become relevant to government concern - and subject to regulation - only insofar as it bore upon matters temporal. Racial distinctions by employers suggest a rough parallel; the school cannot discredit the aptitude of non-believers for strictly earthly vocations or civic participation. It may not teach that Catholics tend to make unsatisfactory mathematicians, or that Jews can’t cook. It may not warn its children to avoid personal relationships with children of non-believers. But note that such a limitation upon temporal stigma is not a restraint unique to religious schools; it is a standard curb on the teaching of the purely secular institution, whether this be Andover or P.S. 97. There is really nothing peculiar here to the faith-based school.

Thus, though the opponent of school choice is correct to worry about schools teaching the temporal inferiority of any group, he is bound in sheer logic to broaden his concern to include educators public as well as private. Just which category of school, by design or choice, most plainly radiates the earthly inferiority of particular groups would be a delicate political issue for the secular critic himself. The obvious candidate for this odious role would be the white suburban public school. (more…)

If one wishes a profound historical-dialectical account of the fate of religion in our governmental schools - all in 200 pages - make Craig S. Engelhardt’s new book, “Education Reform: Confronting the Secular Ideal,” your primer.

If one wishes a profound historical-dialectical account of the fate of religion in our governmental schools - all in 200 pages - make Craig S. Engelhardt’s new book, “Education Reform: Confronting the Secular Ideal,” your primer.

Engelhardt's guiding principle is constant and plain: If society wants schools that nourish moral responsibility, it needs a shared premise concerning the source and ground of that responsibility; and this source must stand outside of, and sovereign to, the individual. Duty is not a personal preference; if it is real, that is because it has been instantiated by an authority external to the person. In contemporary theory, the source of such an authentic personal responsibility is often identified in ways comfortable to the secular mind. There is Kant; there is Rawls.

But in the end, the categorical imperative and the notion of an original human bargain are vaporous. We go on inventing these foundations, but, in moments of moral crisis, such devices do not provide that essential, challenging, universal insight that tells each of us he ought to put justice ahead of his own project. Only a recognition of God’s authority and beneficence can, in the end, ground our grasp of moral responsibility.

This message is repeated at every turn to support the author’s practical and political conviction - that the child cannot mature morally in a pedagogical framework that deliberately evades its own justification. Engelhardt shows in a convincing way that the religious premise was originally at the heart of the public school movement. Americans embraced the government school for a century precisely on the condition that it gave expression to a religious foundation of the good life. When modernism and the Supreme Court gave religion the quietus in public schools, the system serially invented substitutes including “character education,” “progressivism” and “values clarification” – each of which in its way assumed but never identified a grounding source. The result: a drifting and intellectual do-it-yourself moral atmosphere - an invitation to the student to invent his own good. And all too many have accepted.

Engelhardt gives fair treatment to all players in the public school morality game. From the start he provides a generous hearing to the century-and-a-half of well-intending and intelligent minds who paradoxically frustrated their own mission of a religious democracy, first by shortchanging the unpromising Catholic immigrant, then - step by step - pulling the rug from under that transcendental dimension of education which alone could serve their wholesome purpose of training democrats. In this book, every historical player gets to give an accounting of the good he or she intended and the arguments thought to support it; of course, the rebuttals by Engelhardt are potent and even fun to read.

My first and less basic criticism of the book is its slapdash attention to the legal paraphernalia that will be necessary to school choice, if it is to serve the families who now enjoy it the least. (more…)

Editor’s note: Craig S. Engelhardt is a former teacher and school administrator who directs the Waco, Texas-based Society for the Advancement of Christian Education. His new book is “Education Reform: Confronting the Secular Ideal.”

Public education reflects some of America’s highest ideals and is based upon a belief in the value of both the individual and American society. Its existence reflects the belief that all children - regardless of their demographic status - should have the opportunity to grow in and pursue their potential. Its curricula reflect the belief that prosperity, liberty, and peace are rooted in individuals who are knowledgeable, skilled, reasonable, individually reflective, morally responsible, and socially supportive.

I support public education as both an ideal and a “good.” However, I claim public education harbors a systemic flaw that hinders and often prevents our public schools from fulfilling their ideals. Further, I claim this flaw has survived virtually unrecognized and unchallenged for over a century. Is it possible a scientific, astute, experienced, and democratic people could have missed a “flat world” sized flaw in a system so close to their lives and communities? I maintain we have. I have extensively written about it in “Education Reform: Confronting the Secular Ideal.”

In this scholarly book, I attempt to “tease out” the roles religion has played in education from America’s conception to the present. To do this, I start with a functional definition that describes religion as a coherent and foundational set of beliefs and values that provides a framework for reason and a source of motivation for life. Defined functionally, religions are worldviews that may or may not have a deity.

Working from this definition, I discover pre-modern (roughly pre-20th century) public and private education leaders consciously held religion to be central to their efforts. In other words, they believed individuals were shaped by their religious beliefs and the educational nurture of individuals relied upon teaching the foundational beliefs of their communities, extrapolating from pre-existing beliefs, and integrating new facts with those beliefs. The question within 19th century common schools was not whether schools should be religious, but which religious tenets were most integral to and supportive of the American way of life. This educational discernment was not merely due to prejudice or self-centered majoritarian preferences (though these played a role), but to a reasoned, experiential, and historically evident understanding of the roles of religion in society. The exclusive public support of common education seems to have been an attempt to educate non-Protestants toward many of the morals, beliefs, and perspectives considered to be “American” and indebted to the Protestant faith.

So how did secular public education become an “ideal”? First, I note it never was the ideal for the majority of the U.S. population. Even now, given a choice, I believe most parents would likely prefer to send their children to a school reflecting their “religious” views. Secular public education developed in America as a result of the confluence of two mutually supporting public commitments and a national trend - all were philosophically based, but one carried the overwhelming force of law. I believe the complexity of their interplay and the slow pace of change allowed the “flaw” of linking public education with the secular paradigm to survive to our present day with little challenge. (more…)

Editor’s note: This piece is in response to Friday’s guest post from Alex J. Luchenitser of Americans United for Separation of Church and State.

It seems simplest, though scarcely elegant, to reply to attorney Luchenitser’s statements one by one, though I will leave to the lawyers how a school choice tax credit is a state expenditure while tax deductions and tax exemptions are not.

First, it is not true that I assert that states should be forced to fund religious schools; my point is that, if a state chooses to fund private schools through parental school choice, it should not discriminate against those with a religious character. The recent ruling in Duncan v. New Hampshire does precisely that, allowing scholarships derived from tax credits to go to private schools on condition that those schools not be “of any religious sect or denomination,” citing the language of an 1877 amendment to the N.H. Constitution.

By the way, it also does not prevent those scholarships from going to homeschooling families no matter how religious their efforts may be, suggesting religious education is excluded only if you do it with other people. How sensible is that?

I compare this discrimination, in my previous post, with the racial discrimination laws adopted in the South during the same historical period, and I urge that it is similarly unjust and should be challenged by anyone concerned with fairness. Equal treatment is my only claim.

Second, he challenges my conclusion (based on a careful review of the historical evidence detailed in my 24,000-word “expert report”) that the anti-aid (or “Blaine”) provision added to the New Hampshire Constitution in 1877 was the result of anti-Catholic bias. To respond to this I can only offer to provide a copy of my report to anyone who would like to review the evidence with an open mind.

Third, he claims, “the New Hampshire constitution today neither allows anti-Catholic discrimination nor has such an effect.” It is true that today the effect of that particular provision, as applied in the recent ruling, is even-handedly discriminatory against all organized religious groups in favor of groups, no matter how strong their ideological flavor, that claim a secular basis. Is this progress? (more…)