A team of driven educators launched Alane Academy in rural Wauchula, Fla., with the philosophy that excellent character and leadership are equally as important as academics.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Robert Pondiscio, a senior visiting fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, appeared last week on the Fordham Institute’s website. You can read a report on rural school choice from Step Up For Students researchers/writers here.

A common observation made by critics of school choice is that it has little to offer families in rural communities where the population isn’t large enough to support multiple schools, and where transportation is already burdensome. I’ve made the point myself, and I’m a school choice proponent.

These days I live in a small town in upstate New York, whose school district pulls in students from eleven townships scattered across well over 100 square miles. Meaningful choice seems unlikely to be a feature of the educational landscape anytime soon, if ever, in my neck of the woods.

A new Heritage Foundation paper from Jason Bedrick and Matthew Ladner challenges that notion. The 14% of Americans who live in rural areas already have more options than commonly assumed, they argue. For starters, seven in ten rural families live within ten miles of a private elementary school. Counterintuitively, they note the share of rural students in private schools is the same as their urban peers, about 10%.

In Arizona, where both authors live, more than eight in 10 students live in the same zip code as at least one charter school. This point is less compelling when you consider that more than two-thirds of Arizona’s population lives in Phoenix. But the Grand Canyon State has one of the nation’s most robust and popular charter sectors, and a political environment that has long been far more congenial for choice than most other states.

Last year, Arizona expanded eligibility for its K–12 education savings account program to every one of its 1.1 million school-aged students, making it “the gold standard for education choice,” in Bedrick and Ladner’s view. ESAs poll well among Arizona parents, presumably creating conditions congenial to a further flowering of private choice options statewide. If the point is that other states might want to look to Arizona as a model, that point is well-taken.

Rural areas in Arizona and elsewhere are seeing the rise of microschools, which the authors describe as “a modern reimagining of the one-room schoolhouse.” The pair also argue that “high-quality virtual schools are available to anyone with a decent Internet connection.”

One surprising piece of data (to me, at least) is that broadband access is not markedly different in rural America: 72% of country-dwellers have a broadband Internet connection at home, compared 77 and 79% of urban and suburban homes, respectively.

That said, the paper is somewhat blithe about the checkered performance of online learning, particularly during the pandemic.

“Virtual leaning might not be the right fit for every child,” they note. “But for some it opens a world of possibilities they otherwise do not have locally—all without having to leave the rural community that they know and love,” they write. Fair enough.

To continue reading, click here.

Julie Taylor launched Alane Academy in rural Wauchula, Fla., with a team of driven educators who align with her philosophy that excellent character and leadership are equally as important as academics.

Editor’s note: This article, which discusses a Step Up For Students brief authored by Ron Matus and Deva Hankerson, appeared Tuesday on ocpathink.org.

In this year’s Oklahoma elections, school-choice opponents repeatedly claimed that allowing education funding to follow students to any provider would destroy rural schools and produce no benefit for most rural students.

Voters ultimately rejected those claims and overwhelmingly supported school-choice candidates. The strongest support for school-choice candidates often came from rural counties.

Now a new study from Florida shows that school-choice programs have benefited rural students in that state without harm to local public schools.

“It’s a myth repeated so often and for so long it’s come to be accepted as fact: School choice won’t work in rural areas. But just like so many other myths about school choice—that it destroys traditional public schools, that it doesn’t lead to better academic outcomes, that it lacks accountability—the myth about school choice not working in rural areas doesn’t stand up to scrutiny,” wrote Ron Matus and Dava Hankerson, both officials with Step Up for Students.

In their report, “Rerouting … the Myths of Rural Education Choice,” Matus and Hankerson reviewed data on school choice participation in Florida’s rural counties. The report defined a rural county as any county having less than 100 people per square mile. Thirty counties in Florida met that definition while in Oklahoma 68 counties fall into that category, according to publicly available data.

Matus and Hankerson found that the number of state-supported private school choice scholarships grew in Florida’s 30 rural counties from 1,706 income-based choice scholarships in the 2011-12 school year to 6,992 in 2021-22. Statewide, more than 70 percent of families are eligible for Florida’s income-based scholarships and the average annual family income for students on scholarship is $37,731.

The report found the share of rural students enrolled in private schools also surged, rising from 6,450 rural students in 2011 to 10,965 in 2021, an increase of 70%.

To continue reading, click here.

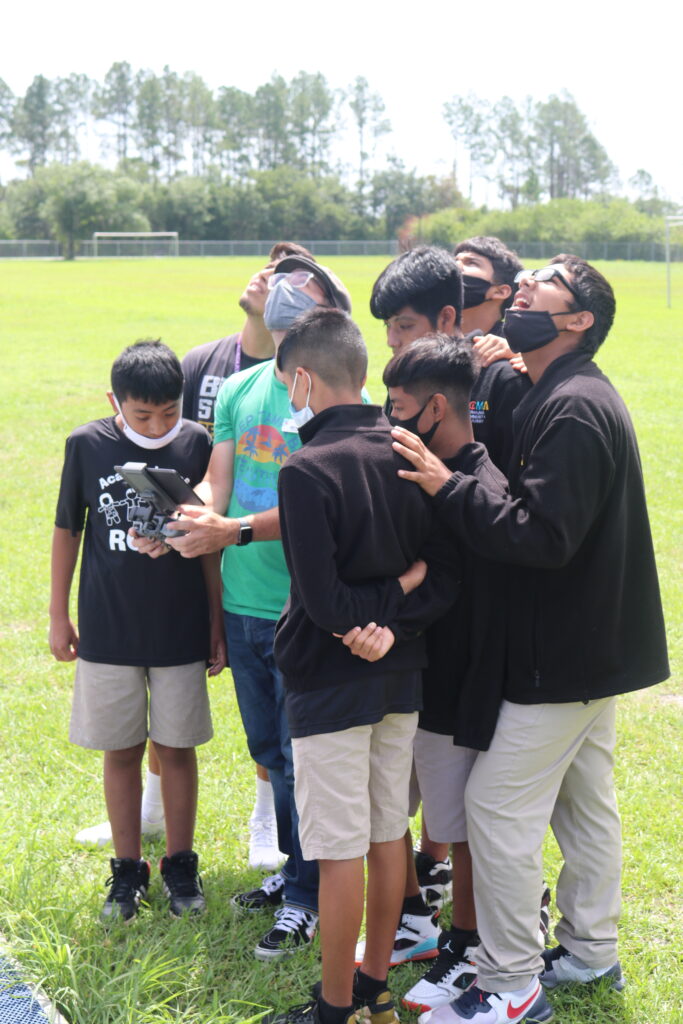

Students at Wimauma Community Academy work with a drone provided by a donor.

The students at Wimauma Community Academy were so determined to win an online math competition that they came to school over the weekend to stay at the top of the leaderboard. At a school where about 95% of the students live below the federal poverty level and don’t have Wi-Fi at home, that was the only way they could compete for the $15,000 prize

Despite their challenges, the students are excelling thanks to Redlands Christian Migrant Association, which established two Florida charter schools in 2000 for children of migrant farmworkers.

“We’re proud that we’re a public charter school and that we are nonprofit,” said Juana Brown, the organization’s director of charter schools. “Some of these babies who started out in our migrant Head Start programs are actually teaching in our schools. It’s a beautiful thing to come full circle.”

The students won the math competition and took home the prize, which school leaders used to build a pavilion on their campus in a rural area southeast of Tampa, Florida. The victory earned them local media attention.

This year, Redlands, which operates the Wimauma school and another charter school in the rural southwest Florida community of Immokalee, has attracted national attention as one of 32 semifinalists for the Yass Prize. Philanthropist Janine Yass founded the awards program in 2021 to reward the innovation in education that resulted from the pandemic with a focus in underserved populations.

Since last year, the awards program, formerly known as the STOP Awards, has broadened its scope to innovation beyond the pandemic. It also included more grants as well as an accelerator to help the entrepreneurs learn from experts and each other.

(John F. Kirtley, founder and chairman of Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog, is part of a blue-ribbon panel of Yass Prize winners from last year and supporters of education choice who are evaluating this year’s entries.)

The 64 quarterfinalists, announced in October, each received a $100,000 award. Those who went on to be named semifinalists received $200,000. The finalists will be announced Dec. 14 and receive $250,000. The overall winner will receive the $1 million Yass Prize. (You can read about last year’s top winner here.)

Wimauma Community Academy serves students in kindergarten through eighth grade whose parents are migrant farmworkers. A sister charter school, Immokalee Community School, serves students in kindergarten through seventh grade.

RCMA Immokalee Academy is one of two charter schools founded by Redlands Christian Migrant Association in 2000. RCMA is one of 32 semifinalists for the $1 million Yass Prize and has received $200,000, which leaders plans to put toward expansion.

RCMA’s mission focuses on improving the quality of life for Florida migrant families through education from “the crib to high school and beyond” and wraparound care that includes training and social services.

The organization operates childcare centers in 21 of Florida’s 67 counties. In addition to providing a safe place for children to learn while their parents are working, the centers also serve as community hubs, linking families to social services such as health care and providing training in such subjects as GED classes, nutrition, parenting, language, and household management.

A group of Mennonites founded the organization in 1965 after seeing young children having to spend all day in unsafe conditions while their parents picked produce in the fields. Kids were being exposed to pesticides and the pests they were targeting. One child died after falling into a drainage ditch.

“Children were sleeping in trucks,” Brown said. “There was no accessible and affordable child care.”

After opening a childcare center to serve the families and seeing few takers, the Mennonites decided to train migrant mothers and employ them to staff the center. After that, the families poured in.

As more families requested expanded education opportunities for their school-aged children, RCMA opened the two elementary schools in 2000.

Ten years later, RCMA added a middle school, RCMA Leadership Academy, to its Wimauma campus. Both Wimauma schools serve a total of 300 students.

Wimauma Academy third graders scored in the top 20 in the state in math. At RCMA Leadership Academy, 29 of the seventh- and eighth-grade scholars entered high school this year with Algebra I credits and nine with Algebra I and geometry. In civics, the seventh graders’ proficiency scores beat the state and county, and eighth graders topped the state and county in science.

Like the school in Wimauma, the Immokalee School received a “B” grade from the state. In May, the Florida Board of Education designated RCMA as an operator in its Schools of Hope program. The designation allows RCMA to open schools in neighborhoods where a traditional public school has been persistently low-performing and/or is within a Florida Opportunity Zone.

The designation makes RCMA eligible for state funds and low-interest loans as the 57-year-old nonprofit organization expands its charter school operations.

“This is the first year our sixth-graders are taking algebra,” Brown said. “We believe our students are extraordinarily talented and gifted and with the right support can be successful.”

In addition to core academic subjects, the schools offer families fresh produce, which ironically is not accessible or affordable to them even though they harvest it.

“Most of them live in food deserts,” Brown said.

So, the students planted their own vegetable gardens to help families with nutritional needs. In Wimauma, the school brought in chickens to help with pest control. Students who cared for the fowl called their group “The Chicken Tenders.”

The organization features alumni success stories on its website. One of its former students, Zulaika Quintero, attended the University of Florida on a full academic scholarship and now is principal at the Immokalee Community Academy.

The Charter School Growth Fund, the largest funder of high performing charter schools in the country, pledges a $1.275 million investment over four years to help RCMA expand its schools.

RCMA plans to open the K-8 Mulberry Community Academy for the 2023-2024 school year, followed by another K-8 school in Immokalee and a K-8 school in Miami-Dade County. But RCMA doesn’t plan to limit its growth to the Sunshine State, Brown said. The nonprofit’s goal is to provide support for those seeking to establish programs in other states to help immigrants.

“I believe our model is one that serves families that are making that transition, and I think we have an educational model that supports the children and the families,” said Brown, who came to the United States from Cuba when she was 7 and knew no English. “We can give you some things we believe can make a big difference.”

Students who are part of the new Hardee Cooperative Learning Center in Wauchula, Florida, participate in an exercise designed by co-op co-founder and director Sandra Shoffner to give them confidence speaking in public while exploring how much they have in common with each other.

WAUCHULA, Fla. – Sandra Shoffner dreamed of starting a homeschool co-op, but she never imagined the reception it would get when it finally happened.

Dozens of parents attended the first open house last month. They enrolled more than 50 kids for the first semester. And so many signed up for the second semester, there’s a waiting list.

“That night, I was just in awe. I’m still in awe,” said Shoffner, a mother of four with degrees in education. “It was surreal and fantastic. I was up there with the mic, literally shaking.”

“The turnout told me the need was insane.”

Home education was on the rise before the pandemic, then skyrocketed because of it. And it’s clear from the new Hardee Cooperative Learning Center in Wauchula, population 4,990, that the movement isn’t limited to cities and suburbs.

Hardee County, 70 miles from Tampa, is a patchwork of citrus groves, cattle ranches and phosphate mines.

A decade ago, it had 118 homeschoolers. Last year, it had 290.

Parents in the co-op say it’s even more important for rural communities to have learning options, because there are so few traditional schools, public or private. The expansion of co-ops, high-quality virtual providers and state-funded education savings accounts (ESAs) – which are more flexible than traditional school choice scholarships – are helping to make home education in rural areas even more viable.

“Bigger communities have a lot of options,” said parent Chelsea Green, who lives in another sprawling rural county next to Hardee. “We don’t.”

Green said she decided to homeschool her children, Tenley, 8, and Railan, 7, after realizing during the pandemic that she could actually do it. Tenley, who has ADHD, chafed under the rigid structure of a neighborhood school.

“It’s more like a rat race,” said Green, a former paraprofessional for district schools. “You have this time to do this, and this time to do that. My daughter isn’t good with a time schedule like that.”

With homeschooling, Tenley is less stressed and more engaged. She no longer needs as much of the ADHD medication that Green has never been comfortable giving her.

Wauchula isn’t an outlier.

Interest in the Hardee Cooperative Learning Center has exceeded expectations of co-founder and director Sandra Shoffner. More than 50 families signed up for the first semester and there’s a waiting list for the second semester.

The number of homeschool students in Florida’s 30 rural counties rose from 6,201 in 2011-12 to 10,207 last year. The sector keeps growing despite an explosion in school choice options, even in rural areas, and without the state support that’s helping those other options.

In raw numbers, homeschooling growth in rural Florida outpaces the growth in charter schools (from 2,673 students to 5,356 students in those counties over that same span) and it’s neck-in-neck with private schools (6,450 to 10,965). As but one manifestation of the trend, it’s easy to find other new co-ops that are thriving off the beaten path, like this one and this one.

Homeschooling would get another boost if Florida’s traditional school choice scholarships offered more flexibility like its ESAs. ESAs can be used for private schools or home schooling, but at present only students with special needs are eligible. In Florida’s rural counties last year, 791 students used them. (The ESAs are officially called the Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities. They’re administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Shoffner’s son Elliott, who is 7 and on the autism spectrum, is one of those ESA students.

Shoffner works part time as executive director of the Hardee County Friends of the Library, and has degrees in elementary education and special education. She began homeschooling almost a decade ago with her two oldest children.

The dream of a co-op followed.

“It’s important for the adults as much as the kids,” Shoffner said. “I wanted that community with other adults with similar interests.”

Shoffner knew homeschool parents could feel a little isolated, especially in a small town. She knew they’d appreciate connecting with other parents while their kids got opportunities to learn from other teachers. So, a few months ago, she and a handful of other DIY homeschool moms decided to give it a go.

The Hardee Cooperative Learning Center is using space in a church. It’s offering 16 classes one day a week for students ages 3 to 19. Seven teachers, all of them parents, are teaching everything from geography and elementary engineering to creative writing and arts and crafts. Shoffner teaches four classes, including Plants 101 and Debate.

One recent Monday, she went over the difference between fact and opinion to the eight teens in her debate class, and explained “red herring” and “ad hominem attack.” She also led an exercise where the students took turns holding a ball of yarn and listing things they liked until another student said, “Me too.” Then they held the thread while tossing the yarn to the other student, who repeated the drill. The point was to 1) practice speaking in public, and 2) to see, as the yarn formed a web, how much everyone had in common.

For homework, Shoffner asked the students to find a partner and choose from one of two topics: The death penalty or legalizing marijuana. She gave them a week to prepare to debate either the pros or cons.

Where the new co-op heads is up to the participating families.

More classes? Different classes? More and/or different days of the week? How about a seasoned math instructor?

The beauty of the co-op is its flexibility and responsiveness.

“What the parents want is absolutely going to shape where this goes,” Shoffner said. “We’re parent led.”

Shoffner said the Hardee Cooperative Learning Center is not faith-based, to distinguish it from other co-ops in the area, although it does offer some Bible-based classes.

It’s also committed to including any family that wants in.

Shoffner said she has been a lifelong advocate for inclusion for persons with special needs, stemming from a sister who is severely intellectually disabled.

“I don’t know how I can fight for inclusion for kids with special needs, then tell someone else I won’t include them,” she said.

Homeschool parents are grateful for the new co-op.

Lisa Dickey said her son, Laremy, 11, was in neighborhood schools through third grade. He struggled academically after several emotional events, including a fire that destroyed the family’s house and led them to move to a different part of the county and a different zoned school.

Dickey is a stay-at-home mom whose husband works for the Mosaic phosphate company. She said she wasn’t sure, at first, if she could homeschool adequately. But Laremy is taking his core academic classes through Florida Virtual School – which he loves – and she found support from other homeschool families.

The co-op is a nice complement, she said. The team building and character building classes are especially good, she said. And the co-op gives Laremy an opportunity to interact and have fun with other students.

“If he had stayed in public school, he would have fallen further behind,” Dickey said. “It’s good to have that choice.”

Especially, Shoffner said, in a rural area.

“We’ve had one option, one way, for so long,” Shoffner said. “Now we have many options. And people want them.”

Kirby Family Farm launched as a homeschool co-op nearly three years ago with 10 students. More than 40 students, most of them elementary and middle school aged, attended during the past school year. More than half came from public schools.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Thursday on chronicleonline.com. You can read a reimaginED post about a homeschool co-op in North Central Florida here.

While students are returning to school this week, not all are going to be in a classroom.

According to the Florida Department of Education, there were 152,109 homeschool students in the state for the 2021-22 academic year and an increase of 69% in the last five years. Numbers rise every year across the country, especially following the school shutdowns during the pandemic.

Parents who choose to homeschool do not have to go through it alone, with online courses, resources, and local groups. The kids are not alone, either, as many join co-ops or other programs.

Sherri Boggess Brice has been leading the Williston Christian Homeschool Group for 19 years. It currently has more than 90 members of all grade levels. The members share information and resources, as well as doing group parties and field trips.

Last year’s excursions included the Endangered Animal Rescue Sanctuary, Hoggetown Medieval Faire, Kanapaha Botanical Gardens and Cedar Key Historical Society, all geared toward older group members. The students also get together to do team sports and holiday parties.

“In my 23 years of homeschool adventures, homeschool kids still go to prom, participate in a graduation ceremony and receive a diploma,” Brice said. “My four daughters entered college straight from my homeschool program. Dual enrollment, college scholarships and Bright Futures all played a part in my children’s education at the upper level.”

“Homeschooling is one of the best alternatives for your child’s education,” she said. “Your child will learn life skills as well as the typical school subjects.”

To continue reading, click here.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id="42" gal_title="Kirby Railroad"]

WILLISTON, Fla. – The Kirby Family Farm isn’t a farm in the usual sense, even if it does produce a few acres of hay and peanuts now and then. It is a farm, though, if you see it like Tracy Kirby sees it.

“Our main crop,” she says, “is kids.”

Ten years ago, Tracy, a former public-school teacher, and her husband, Daryl, bought 110 acres next to this town of 2,700 because, well, Daryl found a century-old train so deep in the woods, squirrels were living in the engine.

The train led to the land. Which led to more trains (nine locomotives and counting). Which led to a mission – helping disadvantaged kids – that the Kirbys have poured their hearts into.

The Kirby operation has 1.3 miles of track, a Ferris wheel, a wooden building that mimics a street front from the Wild West, and a crazy list of other odds and ends that have turned this “farm” into a campy, nothing-else-like-it destination.

The proceeds from Scary Train, Christmas Train, Wild West Weekend and all the other colorful events the Kirbys dream up are plowed into programs for kids – sick kids, foster kids, kids with special needs …

So of course the farm has a home school, too.

Tracy Kirby, left, and Amber Thornton, an assistant teacher at Kirby Family Farm

Tracy Kirby started a homeschool co-op two years ago, wanting to ensure her 6-year-old daughter, Kari, had a community around her. Kari has Marfan syndrome, an inherited disorder that affects connective tissues and can cause heart problems.

The first year, the co-op had 10 students. Then COVID-19 happened. Now it has more than 40, most of them elementary- and middle-school aged, with another 15 on a waiting list. More than half were formerly in public schools.

“I got bombarded,” Kirby said.

Distance learning was especially challenging in remote areas with spotty connectivity, Kirby said. She told the frustrated parents who came to her: “You’re the teacher. But I’ll hold your hand, and you’ll have me in your back pocket.”

Wild as it sounds, this little co-op in a corner of Florida best known for clam farms and cave diving points to the future of public education. It’s teacher empowerment, “learn everywhere” and innovate anywhere all rolled into one.

More teachers like Kirby are finding they have the power to create their own models, especially in states like Florida, where education choice has become mainstream. More parents are seeing the value of options that allow children to learn beyond traditional programs in traditional classrooms.

For icing on the cake, the Kirby co-op chips away at the odd myth that “school choice” can’t work in rural areas. In Florida, there’s plenty of evidence it does. (See here, here, and here.)

To get to the Kirby’s, head west from I-75, halfway between Gainesville and Ocala. Urban sprawl gives way to rolling pasture and log trucks loaded with pines. If you get to a zippy mart with a rooster in the parking lot, you’ve gone too far. But if you see a hearse on the edge of a sorghum field – on the side it says “Scary Train” in pink letters – hey, you’ve made it!

The parents in the co-op represent a cross-section of the community. They’re waitresses and engineers, physical therapists and correctional officers, cashiers and construction company owners. What binds them is this approach to educating kids, and their trust in Tracy Kirby.

Beneath the baseball cap with the Florida logo is a highly skilled educator who knows exactly why so many parents want options.

Kirby was an elementary school teacher for six years. She left the classroom to homeschool when her sons were in middle school. She pulled her oldest, A.J., when he was in eighth grade and having behavior issues. She found out later he was being bullied.

Homeschooling changed everything, fast.

“I saw so much improvement in his confidence and well-being,” she said. “It was eye-opening.”

Garrett’s challenges were academic. With homeschooling, Kirby saw he needed more time with certain subjects, and topics that better held his attention. At one point, the two of them shaped a program of study about birds that included helping with a University of Florida project that required catching, tagging, and tracking them. Garrett loved it.

“I was just able to customize it,” Kirby said. “I had the flexibility.”

Along the way, Kirby attended a convention in Orlando with thousands of other homeschool families. She called it life changing.

“I had 8-year-olds walking up to me, asking me, ‘Can we build an app for Kirby Family Farm?’ I was like, ‘Whaaaaat?!!’ What is this homeschool world?”

Once Kirby began homeschooling, other parents began asking her for help. That led to tutoring. Now Kirby tutors about 15 students in a wide variety of subjects.

Then came the co-op, which has become an umbrella for a wide range of services. Besides classes a few hours once a week, Kirby helps parents design learning programs, find the right curriculum and materials, and prepare the portfolios they need to satisfy home education requirements.

Kirby co-op parent Jennifer MacCord said her 11-year-old son Korbin struggled in a district school, especially during the pandemic. ADHD made it hard for him to stay focused during long stretches of screen time. So about a year ago, she and her husband decided to homeschool him. Now Korbin is excelling, she said, because Kirby helped her create a program that plays to his strengths.

“School and learning should be about catering to the person,” said MacCord, a stay-at-home mom and surgical tech by training. “My son is hands on. He needs hands on.”

Through the co-op, Korbin has built a volcano and dissected owl pellets. He’s worked on public speaking. He’s also overcome his shyness by volunteering to be an actor during the Scary Train production. (Truth be told, Korbin is a very good evil clown.)

“He’s more outgoing,” MacCord said. “He’s found himself.”

Kirby Homeschool Co-op students experience the benefits of technology by removing railroad spikes with a crowbar and then with a battery powered spike puller. The co-op recently received a VELA Education Fund micro-grant to remodel a donated modular office building that will house a computer lab and a “Mommy and Me” space.

At the co-op, the classroom extends into the “farm.” The science lab is in the Wild West building. The kids have learned botany by picking peanuts. They got to literally feel the benefits of technology by removing railroad spikes – first with a crowbar, then with a battery powered spike puller.

When Kirby surveyed co-op parents to ask what they needed the most help with, the majority said science. So, she developed a science lab and shifted the curriculum to include more science.

The lab feels a bit like an open-air barn, with wood beams crossing the ceiling beneath a tin roof. Textbooks are stacked on a table. A periodic table hangs from the walls, along with posters about the water cycle, the human skeleton, the layers of the Earth.

On a recent class day, Kirby kicked off a lesson with a “wonder lab” question: “What do you wonder about … spiders?” The answers:

“I wonder how spiders crawl on the walls.”

“I wonder what the chemical composition of the webs are.”

“I wonder why daddy long legs are arachnids but not spiders.”

In case you’re wondering, the kid who asked the last question is nine years old.

This was also “Takeover Day.” As soon as science ended, a handful of students took over as teachers to show their classmates how to make Halloween crafts. One had picked puppets; another, “spider pops”; another, flying ghosts made from paper cups and crepe streamers. The goal was for students to exercise leadership and communication skills.

And to have fun doing it.

When Kirby asked the kids to give a thumbs up if they’d been working on their creative writing pieces for Halloween, not only did all of them give a thumbs up, some of them jumped up and down.

Kids giddy about writing? In a building that looks like the OK Corral? On a farm full of trains?

What is this homeschool world?

Editor’s note: reimaginED welcomes its newest guest blogger, Garion Frankel, with this post on a viable education choice alternative for rural families.

Editor’s note: reimaginED welcomes its newest guest blogger, Garion Frankel, with this post on a viable education choice alternative for rural families.

The past two years have seen an unprecedented string of victories for parental choice advocates. After the events of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than two dozen states now offer some form of voucher program.

But amid this expansion of school choice, the concerns of rural Americans are often overshadowed. Millions of American students attend a rural school, and many families interpret vouchers of any kind as a threat to their way of life. This resentment often influences policy.

For example, the Texas House of Representatives, based on the support of rural Republicans, added an amendment banning the use of vouchers to the state budget, which will be in effect until 2023.

"The reality is we have plenty of options and choice within our public schools,” said state Rep. Dan Huberty, a Republican who has long opposed voucher-driven school choice.

Rural concerns are valid. Anyone who has ever seen an episode of Friday Night Lights knows what the local public schools can mean to a rural community. Rural schools can employ half a town, and the other half will pack the bleachers for a high school football game.

These are institutions that can’t simply be overlooked. Furthermore, it’s true, at least historically, that rural access to voucher programs has been poor.

But there is now an option that can adequately serve both a single mother from Baltimore and a family with deep roots in rural Wyoming. Education savings accounts can satisfy the needs of all Americans, and arguably strengthen rural schools in the process.

Like traditional vouchers, ESAs enable parents to withdraw from their traditional public school and receive a deposit of public funds into a state-authorized savings account. Families can usually access this account via a debit card, and the money may be used for limited, but varied uses, such as private school tuition and supplemental instruction.

The difference, however, comes in the breadth of ESAs. They are not really vouchers. Instead of being specifically directed towards private schools, ESAs allow families to effectively design an educational program from scratch. In some cases, as with West Virginia’s Hope Scholarship Program, some students can use ESAs to support their public education.

In addition, ESAs can actually increase public school per-student spending. When families elect to participate in an ESA program, they receive only the state-allotted portion of their education. Sure, the public school district wouldn’t receive that portion of their funding, but it would be able to keep the locally sourced revenue that would normally have gone toward serving that student. As such, school districts can increase their per-student spending when ESAs are available.

For rural school districts, this extra spending would be particularly important. Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, rural schools struggled to provide adequate internet services as well as the technology to access them. ESAs could open the door for higher-quality internet or laptops for students to use during class.

On the other hand, those rural families who do want something different would be able to pursue other options without feeling like they are destroying a pillar of their community. Nobody should feel guilty for doing what they think is best for their child’s future, and with ESAs, that choice could ever enhance their community.

There is no time like the present to implement school choice measures, and with ESAs, rural communities could comfortably join the broad, nationwide coalition of parental choice advocates.

There are no more excuses for blocking school choice efforts. Standing against ESAs is neither conservative nor acting in the interest of preserving communities; it is merely selfish and narrow-minded.

Rural communities arguably are the heart and soul of American culture and identity. That should apply to school choice too.

Rural school districts are more likely to be disadvantaged by one-size-fits-all mandates from state legislatures and the Federal government. Yet rural districts, where resources are already spread thin and school are often important employers, are also more likely to be skeptical of school choice programs.

A new policy brief by Dan Fishman in Education Next, argues new schooling options and other education reforms could not only work in rural America but could also help revitalize its communities.

Fishman, a former high school teacher from rural New Mexico, says top-down mandates can stretch the resources of rural schools. While urban districts have the manpower to interpret rules or complete reports, rural districts must rely on a smaller central staff. Although qualified candidates may live in the community, state teaching certification and licensing requirements may leave classrooms unfilled as rural districts struggle to find certified teachers.

According to Fishman, the federal i3 (Investing in Innovation Fund) grant application takes 120 hours at a minimum to complete. Often districts have to pay outside consultants to handle paperwork that may reward the district with about $30 to $90 extra per pupil. Again, rural districts find themselves on the short end of the stick.

So why add more educational options like charter schools, if districts can barely stretch the resources for the existing schools? (more…)