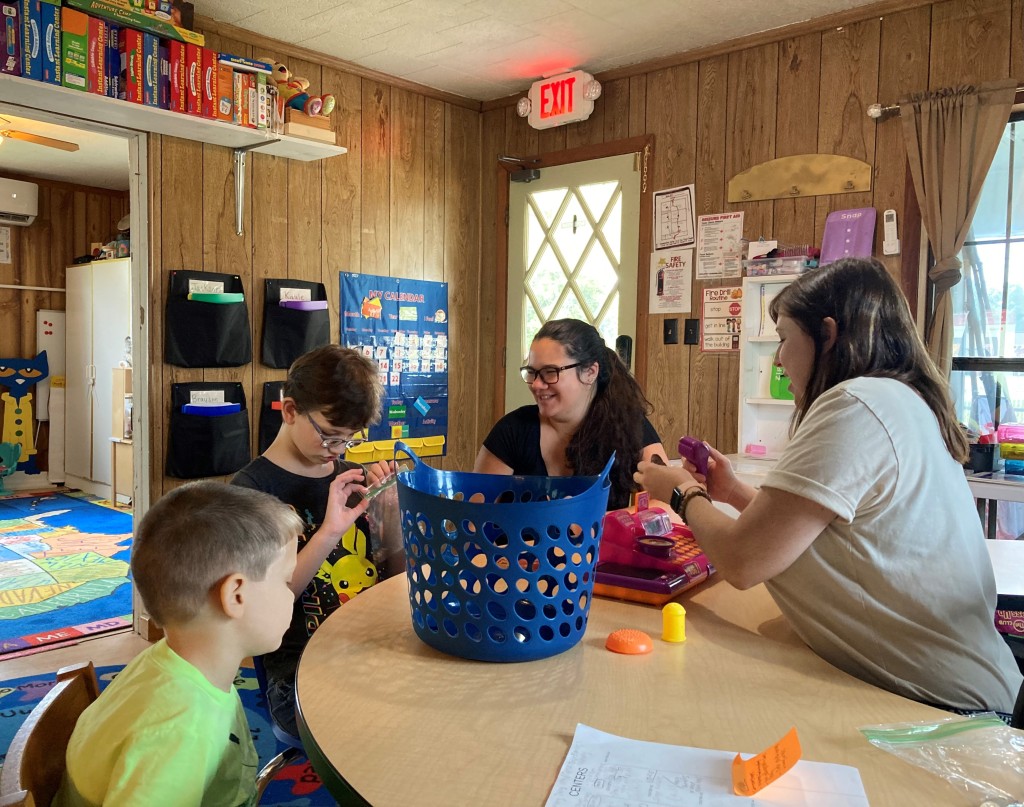

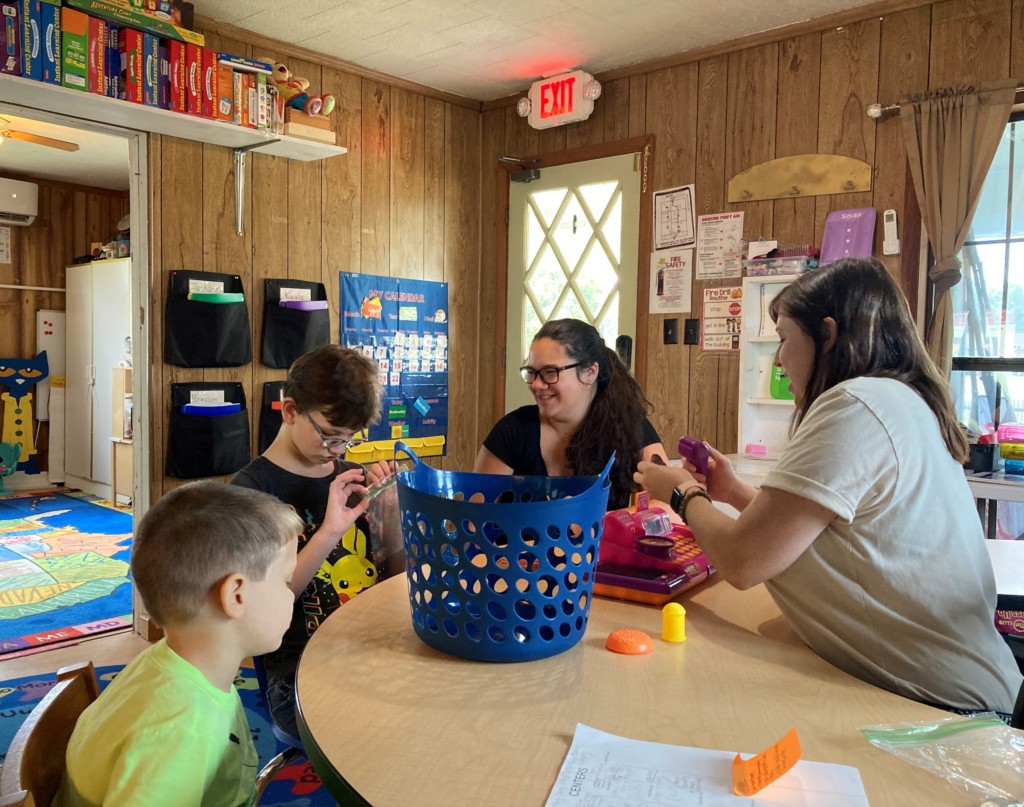

The classroom at Longwings doesn’t look too different from a typical classroom, but much of the the language on the walls is French, and teacher Erica Rimbert (at center) toggles between French and English throughout the day. Rimbert’s daughter, Abilene, sits on her lap.

McALPIN, Fla. – Maybe it stands to reason that in a remote community surrounded by hay fields and pine plantation, students at a new, K-5 microschool would bring baby horses for show-and-tell, and the teacher would secure donations from Tractor Supply to start a garden. But don’t let stereotypes — or tired myths about school choice in rural areas — limit your imagination about the possibilities here.

The academic offerings at Longwings Academy also include coding … and crochet … and French language immersion. As long as the 10 students and their families like it, and they do, the school’s lone teacher can keep doing what she, and they, want.

“To know we don’t have to follow the pacing guide, and the curriculum guide, and do what the district says to do – it’s just liberating,” said Longwings founder Erica Rimbert, another former public school teacher in school-choice-rich Florida who left a classroom to start a school.

Maybe Suwannee County isn’t the first place that comes to mind for education innovation. But another beautiful thing about education choice is it enables resourceful people to launch good ideas, wherever they are.

Suwannee County is Old Florida and Deep South, 20 miles from the Georgia line. It’s best known for the river that shares its name, and it’s so traditional, it didn’t open up to liquor sales (at least legally) until 2011. About 47,000 people call it home, 1,800 of them in unincorporated McAlpin. The latter is big enough for a Dollar General but not a stoplight.

The activities at Longwings reflect the fact that the community it serves has long had strong ties to agriculture. Here, the students pet Trooper, a horse owned by the Rimbert family. Erica Rimbert’s husband, Nick,(right) sometimes rides Trooper to school.

Rimbert and her family moved here last year, wanting a little land to pursue their passion for horses. In southwest Florida, she worked at a district school that served the children of migrant farm workers. Even then, she had fleeting thoughts of starting her own school, but it wasn’t until moving to Suwannee that it became imperative.

The kicker, Rimbert said, was seeing her oldest daughter, then in kindergarten, and her daughter’s peers, not learning basic things their families thought important. In her daughter’s case, it was not having time to fully pick up French, her father’s native language. For some of the other kids, it was not learning more about farming and livestock, even though their families had strong ties to the land.

“That’s what finalized it for me,” Rimbert said. Sometimes with traditional schools, “there are just needs that are unmet.”

Rimbert wasn’t sure families would want what she was offering. Doubts persisted even though a local official told her during the process of securing a school site that “people are going to come out of the woodwork,” and even though 25 families showed up for open house. It wasn’t until the first day of school that she realized this could work.

“People are just looking for something different,” she said.

Even in McAlpin.

Thanks to parent-directed education policies, more can have it. All the students at Longwings use choice scholarships. And in Florida as a whole, 8,558 students in rural counties were using them in 2021-22, according to an analysis we did.

Longwings is a little different from traditional school in some ways, a lot different in others.

It’s in McAlpin’s only strip mall, next to McAlpin Country Diner. Rimbert has the freedom to pivot whenever and however, with instruction and everything else. But her classroom doesn’t look much different from a typical classroom, except for a few signs in French and a French flag that accompanies the American and Florida flags.

Students start the day with the Pledge of Allegiance. They tackle core subjects. They follow Florida state standards. They take formal tests. Most of them take standardized tests, too, though they’re not “high stakes.” (By law, most of the students using choice scholarships in Florida must take a state-approved standardized test every year.)

The French immersion piece is definitely distinctive.

Rimbert toggles between English and French. On Election Day, the students wrote a few sentences that listed, first in English, then in French, what they would do for America if elected president.

The point isn’t just to learn another language, Rimbert said. It’s “to open the door to learning about another world” and yet more worlds beyond that.

“It’s insane. The kids love it,” she said. “They’ve just taken off with the language.”

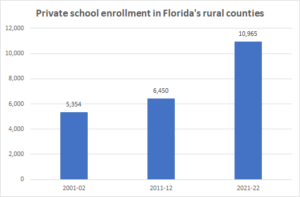

Critics of education choice would have you believe a school like Longwings “can’t work” in rural areas, even though in Florida, they’re increasingly common. In 2000, the year before Florida’s private school choice programs began ramping up, 62 private schools operated in Florida’s 30 rural counties. In 2023, there were 130.

What’s happening in Suwannee represents that bigger picture. On the one hand, a few hundred families over the past decade have migrated to options beyond district schools. On the other, the impact on district enrollment has been modest.

According to state data:

At Longwings, Tracy Walker uses a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities for her 10-year-old son, Jarred. He is classified as gifted and diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. At his prior school, he excelled on standardized tests and earned F’s in some classes.

“He was bored out of his mind,” said Walker, a former Army officer and public school teacher who now breeds horses and sells real estate.

Walker said she was willing to take a chance on Longwings because she could tell Rimbert had the chops to deliver a high-quality program, and to tailor a curriculum that worked for Jarred, who loves math and coding. Rimbert “had so much vision on how to stretch them (her students) further,” Walker said. “I felt like it could be a better fit because it was outside the box.”

At Longwings, Jarred can stand up if he feels fidgety. Rimbert shifts him to more advanced concepts as soon as he shows mastery. He and the other students also apply their skills to real-world scenarios, Walker said, for example, by using what they learned in math to determine the length of fencing and the number of fenceposts they needed for their new garden.

Jarred didn’t like school last year, Walker said. But this year, he’s so excited that “he was disappointed when we were out for the hurricanes.”

Rimbert hopes to switch locations next year to a schoolhouse she’s planning on her family’s property. She wants to stay small but thinks she can grow to 25 students without compromising quality.

Like Walker, she doesn’t think rural families are any less likely than other families to want options. If there’s any doubt, she said, it’s only because they haven’t had as many options to access.

Now, with schools like Longwings, “they’re looking and they’re curious,” Rimbert said. At the end of the day, “everybody wants the best thing for their kid.”

McALPIN, Fla. – Maybe it stands to reason that in a remote community surrounded by hay fields and pine plantation, students at a new, K-5 microschool would bring baby horses for show-and-tell, and the teacher would secure donations from Tractor Supply to start a garden. But don’t let stereotypes — or tired myths about school choice in rural areas — limit your imagination about the possibilities here.

The academic offerings at Longwings Academy also include coding … and crochet … and French language immersion. As long as the 10 students and their families like it, and they do, the school’s lone teacher can keep doing what she, and they, want.

“To know we don’t have to follow the pacing guide, and the curriculum guide, and do what the district says to do – it’s just liberating,” said Longwings founder Erica Rimbert, another former public school teacher in school-choice-rich Florida who left a classroom to start a school.

Maybe Suwannee County isn’t the first place that comes to mind for education innovation. But another beautiful thing about education choice is it enables resourceful people to launch good ideas, wherever they are.

Suwannee County is Old Florida and Deep South, 20 miles from the Georgia line. It’s best known for the river that shares its name, and it’s so traditional, it didn’t open up to liquor sales (at least legally) until 2011. About 47,000 people call it home, 1,800 of them in unincorporated McAlpin. The latter is big enough for a Dollar General but not a stoplight.

Rimbert and her family moved here last year, wanting a little land to pursue their passion for horses. In southwest Florida, she worked at a district school that served the children of migrant farm workers. Even then, she had fleeting thoughts of starting her own school, but it wasn’t until moving to Suwannee that it became imperative.

The kicker, Rimbert said, was seeing her oldest daughter, then in kindergarten, and her daughter’s peers, not learning basic things their families thought important. In her daughter’s case, it was not having time to fully pick up French, her father’s native language. For some of the other kids, it was not learning more about farming and livestock, even though their families had strong ties to the land.

“That’s what finalized it for me,” Rimbert said. Sometimes with traditional schools, “there are just needs that are unmet.”

Rimbert wasn’t sure families would want what she was offering. Doubts persisted even though a local official told her during the process of securing a school site that “people are going to come out of the woodwork,” and even though 25 families showed up for open house. It wasn’t until the first day of school that she realized this could work.

“People are just looking for something different,” she said.

Even in McAlpin.

Thanks to parent-directed education policies, more can have it. All the students at Longwings use choice scholarships. And in Florida as a whole, 8,558 students in rural counties were using them in 2021-22, according to an analysis we did.

Longwings is a little different from traditional school in some ways, a lot different in others.

It’s in McAlpin’s only strip mall, next to McAlpin Country Diner. Rimbert has the freedom to pivot whenever and however, with instruction and everything else. But her classroom doesn’t look much different from a typical classroom, except for a few signs in French and a French flag that accompanies the American and Florida flags.

Students start the day with the Pledge of Allegiance. They tackle core subjects. They follow Florida state standards. They take formal tests. Most of them take standardized tests, too, though they’re not “high stakes.” (By law, most of the students using choice scholarships in Florida must take a state-approved standardized test every year.)

The French immersion piece is definitely distinctive.

Rimbert toggles between English and French. On Election Day, the students wrote a few sentences that listed, first in English, then in French, what they would do for America if elected president.

The point isn’t just to learn another language, Rimbert said. It’s “to open the door to learning about another world” and yet more worlds beyond that.

“It’s insane. The kids love it,” she said. “They’ve just taken off with the language.”

Critics of education choice would have you believe a school like Longwings “can’t work” in rural areas, even though in Florida, they’re increasingly common. In 2000, the year before Florida’s private school choice programs began ramping up, 62 private schools operated in Florida’s 30 rural counties. In 2023, there were 130.

What’s happening in Suwannee represents that bigger picture. On the one hand, a few hundred families over the past decade have migrated to options beyond district schools. On the other, the impact on district enrollment has been modest.

According to state data:

At Longwings, Tracy Walker uses a Family Empowerment Scholarship for Students with Unique Abilities for her 10-year-old son, Jarred. He is classified as gifted and diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. At his prior school, he excelled on standardized tests and earned F’s in some classes.

“He was bored out of his mind,” said Walker, a former Army officer and public school teacher who now breeds horses and sells real estate.

Walker said she was willing to take a chance on Longwings because she could tell Rimbert had the chops to deliver a high-quality program, and to tailor a curriculum that worked for Jarred, who loves math and coding. Rimbert “had so much vision on how to stretch them (her students) further,” Walker said. “I felt like it could be a better fit because it was outside the box.”

At Longwings, Jarred can stand up if he feels fidgety. Rimbert shifts him to more advanced concepts as soon as he shows mastery. He and the other students also apply their skills to real-world scenarios, Walker said, for example, by using what they learned in math to determine the length of fencing and the number of fenceposts they needed for their new garden.

Jarred didn’t like school last year, Walker said. But this year, he’s so excited that “he was disappointed when we were out for the hurricanes.”

Rimbert hopes to switch locations next year to a schoolhouse she’s planning on her family’s property. She wants to stay small but thinks she can grow to 25 students without compromising quality.

Like Walker, she doesn’t think rural families are any less likely than other families to want options. If there’s any doubt, she said, it’s only because they haven’t had as many options to access.

Now, with schools like Longwings, “they’re looking and they’re curious,” Rimbert said. At the end of the day, “everybody wants the best thing for their kid.”

Jason Bedrick and I co-authored a new study for the Heritage Foundation last week in which we test an assertion made by Texas choice opponents: choice will destroy rural education. Opponents bandy this assertion as if it were a self-evident fact, but can the assertion withstand scrutiny?

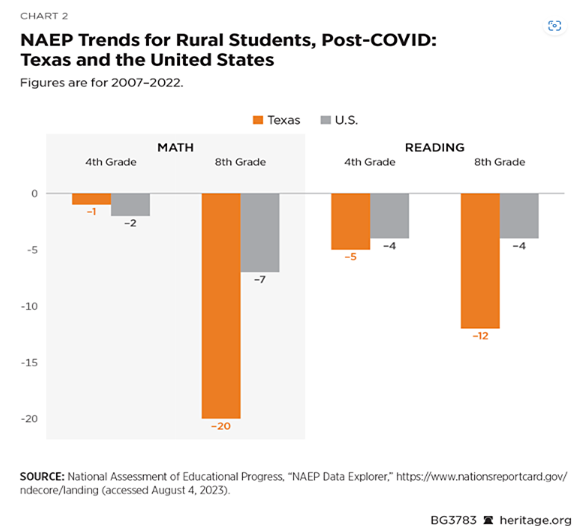

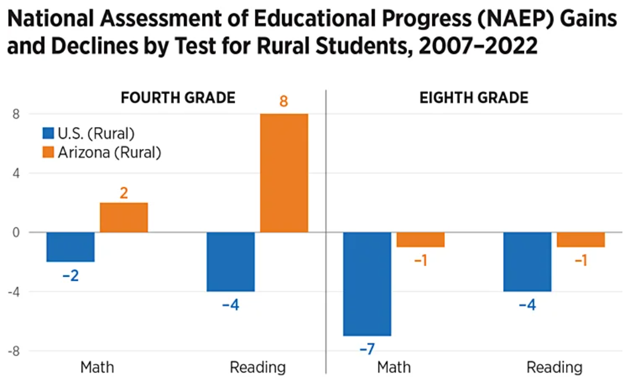

Sadly, we noted that Texas public schools seemed to be doing a rather remarkable job of damaging student learning in the absence of choice. The National Assessment of Educational Progress contains data on rural achievement starting in 2007. It’s not pretty in rural Texas:

On these exams 10 points roughly equals a grade level worth of progress. Unfortunately, this means that Texas eighth graders demonstrated a command of mathematics in 2022 roughly equivalent to what we would have expected out of a group of Texas sixth graders in 2005. COVID-19 does not account for all of this decline. Between 2007 and 2019, eighth grade students saw approximately a grade level decline in math achievement, and the state suffered another grade level drop between 2019 and 2022.

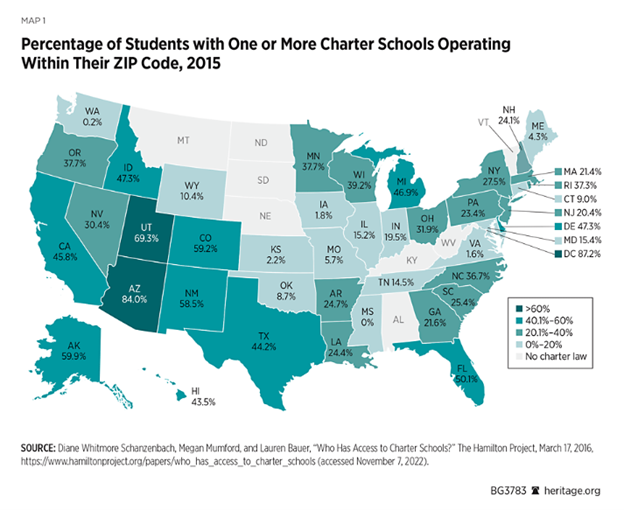

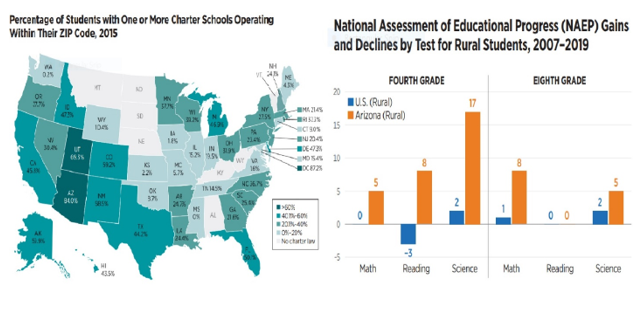

To make the case for choice in rural communities more concrete and less theoretical, we compared academic trends in rural Texas with academic trends in rural Arizona. Arizona has the nation’s largest and most geographically inclusive charter sector (see map above), a very active system of district open enrollment in which nearly all districts participate, tax credit scholarships, ESAs, state funded microschools, homeschooling, and digital learning options.

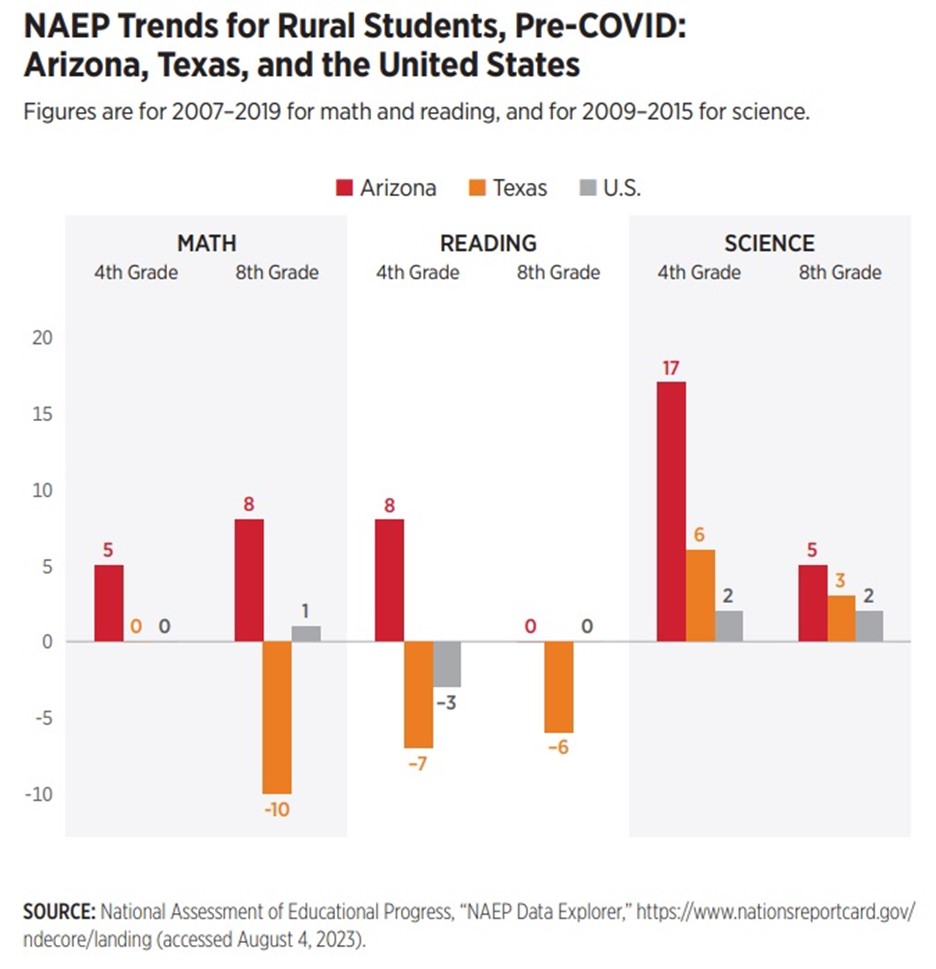

All of these options reach into rural Arizona communities. Has Arizona rural education suffered “destruction?” No. All Arizona school districts that were educating students in 1993 (the year before the advent of choice) are still educating students in 2023. Moreover, unlike Texas, the academic trends for rural Arizona students have been positive:

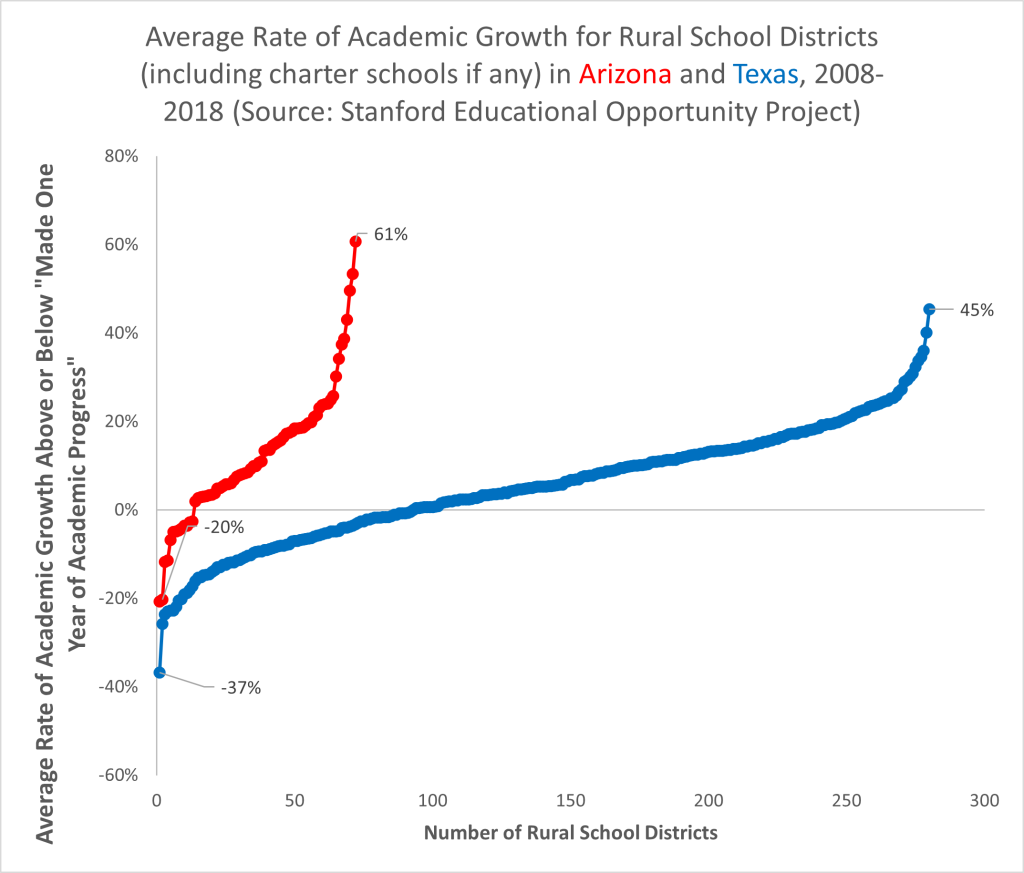

Arizona rural school districts didn’t get the apocalyptic destruction memo. They not only still exist, but their outcomes also improved over time. The Stanford Educational Opportunity project provides a separate source of data showing a similar trend. Stanford scholars linked state testing data in grades 3-8 to enable comparisons across jurisdictions for the 2008-2018 period. Academic growth represents the best measure of school quality, and the project provides growth data for rural school districts (while averaging in charter scores with those of the district in which they reside).

This is my “friendly neighborhood school choice mad scientist makes an excel chart” presentation of that data for rural districts in Arizona and Texas:

And this is the much-improved version of the same data from the data-wizards at Heritage:

The choice-induced death of rural education appears to have been greatly exaggerated. Choice will be rapidly growing in rural areas of many states in the aftermath of the 2023 legislative sessions. Texas families and teachers deserve these freedoms as well. Arizona lawmakers have empowered teachers to create their own schools and families to sort between schools to find the best fits. Rural teachers and students benefit from variety just like everyone else. Rural Texans have nothing to lose and much to gain from choice.

Editor’s note: This is the third video in our series on school choice in rural areas. You can check out the first two here and here. And you can see our paper on the topic, “Rerouting the Myths of Rural Education Choice,” here.

ED Corps High School is a home-grown private school in a part of Florida best known for oysters.

It’s the pearl in the oyster.

Tiny and hidden but incredibly valuable.

A community nonprofit created ED Corps a few years ago to expand opportunities for young people in Franklin County. Franklin County is all of 12,000 people, its biggest towns being Eastpoint (population 2,614), Apalachicola (population 2,341), and Carrabelle (population 2,606).

Life here is woods and water. So ED Corps students spend a good bit of time outdoors, mostly working on conservation projects that help sustain fishing and forestry.

As you’ll see in our new video, they love it.

Right now the school has 11 students, almost all of them using school choice scholarships.

One of the coolest things about school choice is that it allows solutions to come from every direction, whether that’s in a rural community or urban community or any other kind of community.

ED Corps is another beautiful example. The people of Franklin County are so modest, they’d never think to boast about the innovative school they created. So we get to do that.

Enjoy the video.

Jackson Hole Classical Academy in Jackson, Wyoming, one of 37 private schools in the state serving more than 2,700 students, is a private K-12 school in the classical, liberal arts tradition. Its mission is to cultivate wisdom and virtue in students so that they can contribute to a flourishing and free society.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Center for Education Policy, and Matt Ladner, director of the Arizona Center for Student Opportunity at the Arizona Charter School Association and reimaginED executive editor, appeared Monday on The Heritage Foundation’s website.

All children in Wyoming should have access to the highest quality education possible,” declared Gov. Mark Gordon, a Republican, in his recent proclamation declaring January 22-28 School Choice Week.

“Educational variety not only helps diversify our economy, but also enhances the vibrancy of our community.”

The Wyoming Legislature will soon consider a proposal to give families greater freedom to choose learning environments that align with their values and meet their children’s individual learning needs.

Education savings accounts, or ESAs, let families access state funds to pay for private school tuition, tutoring, textbooks, online courses, special needs therapy and numerous other educational expenses.

Ten states have already adopted ESA policies, including five in the last two years. It’s not hard to understand why.

The pandemic—and especially district schools’ response to it—awakened parents to the need for education choice. Unnecessarily long school shutdowns, mask mandates and concerns over the politicization of the classroom have propelled public support for education choice policies, like ESAs, to all-time highs.

In a RealClearPolitics poll last year, more than seven in 10 Americans said they supported education choice. But not everyone is on board. The teachers’ unions and their allies are doing everything they can to block families from accessing alternatives to the district school system.

In an effort to peel away votes from Wyoming legislators representing rural areas, opponents of ESAs are arguing that choice policies either don’t benefit rural areas or are harmful to rural district schools.

For example, the union-funded National Coalition for Public Education claims that education choice policies “don’t provide an actual choice for students living in rural areas” because the nearest private school is far away, therefore “students would often be required to endure long, costly commutes.”

Meanwhile, Carol Corbett Burris, the NCPE’s executive director, frets that education choice policies would supposedly create a “death spiral” for district schools “especially in rural areas” because when “kids leave the system, they leave behind all kinds of stranded costs.”

To continue reading, click here.

Bristol, Florida, population 996, is home to beloved, home-grown Gold Star Private Academy. Every student at Gold Star uses state-funded school choice scholarships.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Monday on iwf.org. To watch a video created by Step Up For Students featuring Gold Star Private Academy, click here.

In Starbuck, Minnesota, parents were devastated to learn that the local school district, a major employer in the area and bedrock of the community, was set to close due to declining enrollment. Instead of attending their local school, students would have to bus over to the next town.

But thanks to Minnesota’s charter school laws, parents, teachers, and community volunteers banded together to open Glacial Hills Elementary, a community-run charter school that serves 91 students, including several students with special needs.

Though operating such a small school is not without its challenges, small class sizes, frequent outdoor activities, and a focus on special education have helped Starbuck children excel academically without leaving their town.

In Questa, New Mexico, population 1,770, the public schools are alive and well, but 50 K-8 students have opted to attend Roots and Wings Community School. Founded by New Mexico educators who spent two years building relationships with local officials and parents before opening their school, Roots and Wings focuses on expeditionary learning and extended outdoor activities in a multigrade classroom setting.

Students at this unique school consistently score higher on state reading and math tests than their public school counterparts and with 76% of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch, the school is also providing high-quality education to economically disadvantaged students.

In Bristol, Florida, a town of only 996, a family of educators opened a special needs private school after years of watching children with autism, Phelan-McDermind syndrome, and other challenges struggle through public school. Today Gold Star Private Academy serves 17 students with a wide spectrum of special needs and allows parents to access the care their children need without moving to a bigger city.

These schools, along with countless other charter and private schools and microschools serving small towns, show that school choice is a boon to every community regardless of size.

To continue reading, click here.

Grace Community School in a rural area of Tyler, Texas, one of 1,819 private schools in the state serving nearly 309,000 students, seeks to create a more inclusive environment so that families who have been traditionally underserved by Christian education can fully share their gifts and talents for the growth and benefit of the body of Christ.

Editor’s note: This analysis appeared Monday on thetexan.news.

A new poll from the University of Houston’s Hobby School of Public Affairs indicates strong support for school choice in the Lone Star State, even among minorities and rural communities with fewer options.

Conducted in January 2023, the survey asked 1,200 respondents from across the state about taxpayer-funded vouchers that could be used to attend private or religious schools and tax credits for individuals and corporate donations that pay for private school scholarships.

According to results released Monday, 61% of Texans support educational vouchers for low-income families and 53% support vouchers for all families regardless of income. Among Black respondents, 78% said they support vouchers for low-income families and 65% support vouchers for all.

Support was high among Latinos as well, with 64% in favor of vouchers for low-income parents and 54% in favor of vouchers for all parents.

Both minority groups also supported tax credits for school choice scholarships for low-income families with 79% of Black and 63% of Latino respondents favoring the proposal.

Although in previous years representatives from rural communities have expressed opposition to legislation allowing parents to use tax dollars for the school of their choice, the survey found 59% of respondents in rural counties favored vouchers and 62% for all families regardless of income.

When parsed by party affiliation, the poll found 57% of all Democrats, 78% of Black Democrats, and 57% of Latino Democrats supported vouchers for low-income families. Only white Democrats expressed opposition.

To continue reading, click here.

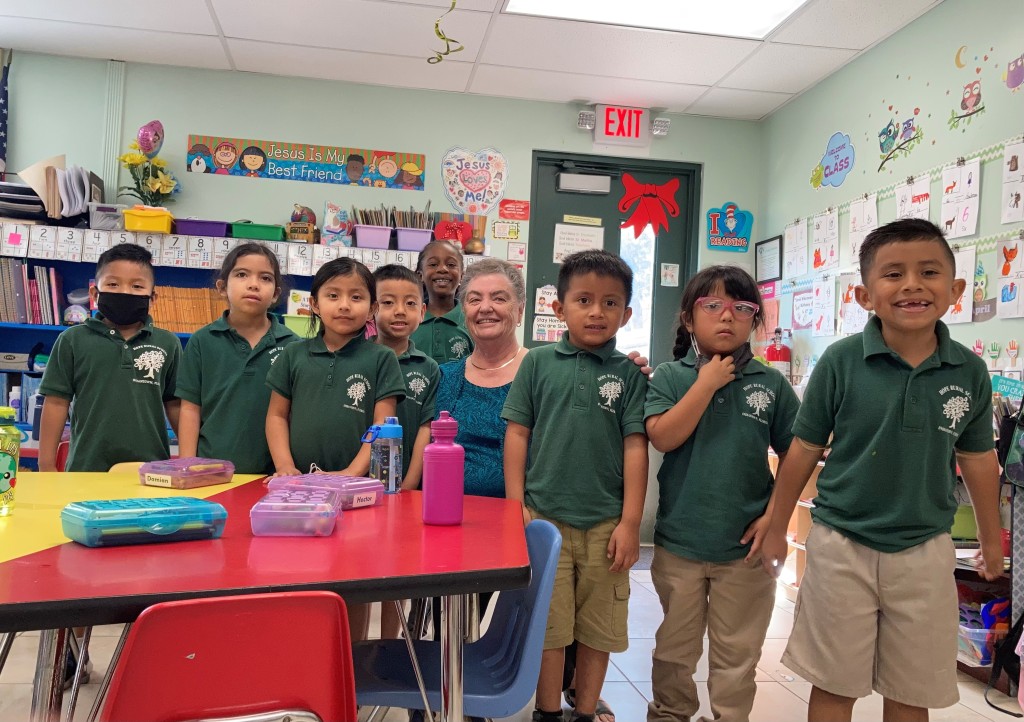

Sister Elizabeth Dunn, center, director of Hope Rural School in the Florida city of Indiantown, population 6,560, believes private schools and public school districts can maintain good relationships. “We don’t compare ourselves,” she says. “We work together. We value what each other is doing.”

The population of rural America has declined by 12.5% since the 2000 Census, but it could be poised for a comeback. Education freedom has a large role to play.

In Rustic Renaissance: Education Choice in Rural America, Jason Bedrick, a research fellow in the Center for Education Policy at The Heritage Foundation, and I explore two mutually exclusive claims made by choice opponents: first, that choice has nothing to offer rural communities because of a lack of choice schools; and second, that school choice programs will destroy rural school districts as families flee to their innumerable other options.

Obviously, these claims cannot both be true, and in fact, both are false. To reverse the decline, rural America desperately needs young families, and a rural education renaissance beckons in the return of the one-room schoolhouse.

Bedrick and I examine the rural claims of school choice opponents by examining the state with the greatest amount of school choice: Arizona. Rural families in Arizona have, by a wide margin, had the greatest access to various choice options for the longest period of time.

In 1994, the Legislature created charter schools and district open enrollment. Arizona now has the nation’s largest charter school sector, and in fact has more rural charter schools than the total number of charter schools in 16 different states with charter school laws: Alabama, Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Washington, and Wyoming.

In 1997, Arizona lawmakers created the nation’s first tuition tax credit program which subsequently has been expanded several times. Then in 2011, Arizona lawmakers created the nation’s first education savings account program.

The graphics on the left show the percentage of students by state with one or more charter schools operating in their zip code as calculated by the Brookings Institute for the 2014-15 school year. Arizona was by far in first place with 84% of students having one or more charter schools in their zip code. This likely underestimates the role of charter schools in Arizona, as many zip codes fall into the “or more” category in the Grand Canyon State.

Did Arizona’s rural school districts wither up and die under the assault of school choice? Hardly. In fact, quite the opposite has occurred. The National Center for Education Statistics listed 224 regular school districts in Arizona in 1993, the year before choice began. In 2019, the same source listed 226 Arizona regular school districts.

The left part of the chart shows NAEP rural trends for all six exams from the earliest date possible (2007 for Math and Reading, 2009 for Science) to the latest point possible before the COVID-19 pandemic (2019 for Math and Reading, 2015 for Science).

The COVID-19 pandemic hit hard in rural Arizona, especially in Native American communities (Arizona has the nation’s second largest Native American student population and many live in rural communities). When 2022 NAEP scores were released, rural Arizona had ground to make up but demonstrated better progress than the nation as a whole, as seen in the chart below.

Microschools hold a special promise for rural America. Population density always has been a deterrent to the growth of large choice schools in rural communities, and the advent of higher borrowing and construction costs will only further the trend.

Microschools, however, often operate out of informal community spaces and homes and thus do not require either high-population density or expensive capital investment. A more pluralistic set of schooling options will help attract and retain young families, who are a large part of rural America’s most urgent need.

As Step Up For Students’ Ron Matus has documented here and here, former public school teachers are flourishing in rural Florida. This speaks to the traditions of rural America, that “spirit of association” that Alexis de Tocqueville noted as the uniquely American method of challenges through voluntary association.

“One size fits all” schools actually fit few in rural America and elsewhere. Academic stagnation and population decline can successfully be combatted by allowing voluntary associations and exchange to flourish in rural American education.

Rural families have nothing to lose and a world to gain by rediscovering the promise of the one-room schoolhouse.

Kaylee Tuck, daughter of Andy Tuck, a member of the Florida Transportation Commission who served as vice chair of the Florida State Board of Education, described herself as “the heartland conservative" and a pro-Trump, pro-gun, pro-life candidate in her successful bid to become a member of the Florida House of Representatives in 2020.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Republican Rep. Kaylee Tuck, who chairs the Florida House Subcommittee on Education Choice and Innovation, appeared Friday on foxnews.com

For years, school choice opponents in states like Iowa and Texas have gotten away with spreading myths about school choice to scare people in rural areas.

They’ve said school choice can’t work in rural areas because there aren’t enough private schools, and that all the money for choice scholarships will go to private schools in the cities. Then, at the same time, they’ve tried to argue that choice will wreck rural public schools and the rural communities that love and depend on them.

In Oklahoma this year, the Democratic candidate for governor even made it a pillar of her losing campaign to say school choice was a "rural school killer."

None of that is true. I know, because I’m a state lawmaker who represents one of the most rural areas in Florida, a state that’s been a school choice leader for 20 years.

School choice helped elevate Florida from being one of the worst education states in America to No. 3 in K-12 achievement. And every year, thousands of rural families experience the life-changing upside of having options.

I am privileged to represent four rural counties in a region called the Florida Heartland. We’re not the Florida they put on postcards. Cattle and citrus are some of our biggest industries, and the tourists we get tend to like racing (at Sebring International Raceway) and bass fishing (on Lake Okeechobee).

The people in my district are resourceful and hard-working, the kind who make rural communities the backbone of America.

They value school choice.

A decade ago, 390 students in my district used state-funded school choice scholarships or state-funded education savings accounts. Last year, more than 1,500 did.

Statewide over that same period, the number of choice scholarship students in Florida’s 30 rural counties grew from 2,547 to about 8,500, according to a new report from Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that administers Florida’s choice scholarships.

That’s a lot of rural families accessing options. But how did they find those options if supposedly there aren’t any private schools in rural areas?

There have always been private schools in rural areas, even if they tend to be fewer and smaller just like the public schools in rural areas. But supply has also grown to meet demand. Since school choice got rolling in Florida, the number of private schools in rural counties has nearly doubled. In my district, they’ve grown from 15 to 25.

Alane Academy in Wauchula, a town of 5,000 people in my district, is one of them. A former school district Teacher of the Year started the school a decade ago because she wanted more flexibility with everything from curriculum to scheduling to assessments.

What she created is top-notch – and a Godsend for families whose children were struggling in traditional schools. Nearly 70% of her students use choice scholarships.

"When you think of private schools coming into small towns, we’re not these big bad people, corporate organizations trying to come in and take over the school system," the founder said. The schools are started by "people just like myself, who grew up in that area, love that area, and just want to provide another choice."

Our community is stronger with schools like Alane Academy. And here’s the kicker: At the same time school choice has been helping thousands of rural families, it has not been undermining rural school districts.

In the past 10 years, the share of rural Florida students enrolled in private schools has risen 2.4 percentage points, to 6.9%. In my district, it’s gone from 4.7% to 7.3%. That’s it, even though more than 70% of Florida families are eligible for choice scholarships.

Across America, next year’s legislative sessions are just around the corner, and school choice opponents know choice has the momentum. They will double down on misinformation in an effort to stem the tide. But the facts on the ground show choice is a plus, including for rural areas.

Rural lawmakers should embrace choice. Rural families and communities will be even stronger when they do.

Gold Star Private Academy in Bristol, Florida, adheres to an educational philosophy that presumes student competence, valuing family as part of its team and focusing on service, compassion, and connection. The school serves students with special needs, all of whom use state-funded school choice scholarships.

Editor's note: In keeping with our year-end tradition, the team at reimaginED reviewed our work over the past 12 months to find stories and commentaries that represent our best content of 2022. This post from Step Up For Students' Ron Matus is the third in our series.

BRISTOL, Fla. – Liberty County is half covered by a national forest. It’s wall-to-wall pine trees. Its only incorporated city has 996 people, and they’re outnumbered by bears.

BRISTOL, Fla. – Liberty County is half covered by a national forest. It’s wall-to-wall pine trees. Its only incorporated city has 996 people, and they’re outnumbered by bears.

Even here, though, school choice has taken root.

Four years ago, a tight-knit family of educators who worked in local public schools for generations opened Gold Star Private Academy.

Gold Star serves students with special needs. All of them use state-funded school choice scholarships. And their parents describe it with terms like “life changing” and “total miracle” and “the greatest school on the face of the Earth.”

Donna Franklin enrolled her son Brayden, who is 15 and has Down syndrome, after four other schools in three counties. At one of them, staff recommended corporal punishment be incorporated into Brayden’s behavioral plan. At another, an aide dragged him down a hallway.

Liberty County in the Florida Panhandle is the Sunshine State’s most rural county, with 9.5 people per square mile. If it were a state, Liberty would be No. 47 in population density, between North Dakota (11.3 people per square mile) and Montana (7.5 people per square mile).

Franklin gave home schooling a shot, but Brayden, she said, needed the social immersion of a full school experience.

So nothing worked – until Gold Star.

“If Gold Star had been here 12 years ago, he’d have had an entirely different childhood experience,” said Franklin, a registered nurse and hospice administrator. “I can’t express enough the need for choice. And the need for schools like this to be everywhere.”

Gold Star Private Academy is another good example of what happens when public education funding follows the child.

Even in a town with one stop light, supply grows to meet demand.

In the last 20 years, the number of private school students in Florida’s 30 rural counties has doubled, from 5,354 to 10,965, according to state data. About 70 percent of them use school choice scholarships.

Meanwhile, the number of private schools in those counties has grown from 69 to 120.

“If you can do this in Bristol,” said another Gold Star parent, Marlene McAllister, “you can do this anywhere.”

***

Gold Star Private Academy was co-founded in 2018 by (from left to right) Johnette Wahlquist, Sally Sims, Jordan Wahlquist, Janna Hill and Kalynn Richardson. They decided to start the school after hearing a friend, a former school district administrator, describe how she started her own private school in another rural county. “We’re educators,” Hill said. “We thought we may as well do it ourselves.”

Gold Star is a family affair.

Sisters Janna Hill (a former district science teacher) and Johnette Wahlquist (a former district nurse) co-founded the school with Wahlquist’s daughter Kalynn Richardson (also a former district nurse); Wahlquist’s daughter-in-law Jordan Wahlquist (a former district speech pathologist); and Jordan’s mother, Sally Sims (another former district science teacher).

Altogether, the family has more than 200 years of combined experience working in local public schools, including three members who were former superintendents.

At one point, the sisters were opponents of school choice.

At one point, Hill led the local teachers union.

But times change.

Gold Star Private Academy was born after a decade of frustration, after family members watched their children and grandchildren struggle in the same schools they worked in.

“I didn’t understand what the parents were going through until I experienced it myself,” Johnette Wahlquist said. “Now I could see the inadequacies and the holes in the system.”

Johnette’s son Christopher, 19, is diagnosed with MPS1, a rare genetic condition that left him with auditory and visual impairments and a tracheostomy to breathe.

Her granddaughter Grey, 10, is diagnosed with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, another rare genetic condition that can cause speech and other developmental delays.

Her grandson Blaine, 11, is on the autism spectrum.

In ways big and small, traditional schools didn’t work for them.

Christopher didn’t get the alternative communication and hearing impaired services he needed. Grey often did not have the fully trained, full-time aide she was required to have. In Blaine’s case, some staff members suggested his mom find another school.

So she did – by helping to create one.

In Florida, this is becoming a common story. A growing number of private schools in Florida – including some in rural counties like this one and this one – are being started by former public school educators.

In the spring of 2018, the Hill and Wahlquist family was at a get-together with friends that included a former district administrator. The administrator had moved to another rural county and, with the help of school choice scholarships, set up a school for students with special needs. (Those scholarships are administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

After another rough year, nobody in the family wanted Grey and Blaine back in the same schools. So when the friend described how she opened her own school, the family members looked at each other and said, “Why can’t we?”

They poured over a chart showing scholarship funding amounts for student with special needs. On average, those scholarships are worth about $10,000 each.

The math added up.

The family found a building they could rent at a reasonable rate. A few months later, they opened Gold Star Private Academy, named in honor of an uncle who died in World War II.

That first year, the school had six students.

Last year, it had 17 – and a waiting list.

This fall, Gold Star is planning to move into another building with three times the space.

The family isn’t sure how big the school should get. They’d like to also serve general education students. The bigger building will give them options.

***

Traditional schools didn’t work for Brayson McAllister, so his mom, Marlene McAllister, enrolled him in Gold Star. Brayson, 7, is autistic and blind and has a brain development condition called septo-optic dysplasia. Brayson can learn and play complicated pieces on the piano after just a couple of listens, but with subjects like math, he needs more time and repetition to stay on track. Enrolling Brayson in Gold Star, Marlene McAllister said, was “the best move I ever made.”

In the meantime, multiple families are grateful Gold Star gave them an option.

Jade Hug said her daughter, Keira, who is 6 years old and on the autism spectrum, couldn’t keep pace with the general education students she was mainstreamed with.

Her family considered moving to Tallahassee, an hour away, so they could enroll Keira in another school that serves special needs students. But it wasn’t a given the other school would be better and the Hugs would have to leave friends and family behind.

Gold Star turned out to be a “game changer,” said Hug, a stay-a-home mom and former nurse – not only because Keira got a school that worked for her, but because the family could stay rooted in their community. “That was one of the best things about it,” she said.

Hug also credited Gold Star staff with constantly updating her about resources and strategies that might help Keira – and communicating in down-to-earth terms that didn’t overwhelm her.

The world of special needs can be “intimidating,” Hug said. “The people at Gold Star say, “We’ll help you. We’ll teach you.’ “

Janna and Johnette said most of the children in their family continue to attend public schools and do well in them. The school and the district, they said, have a good relationship.

One Gold Star student who struggled in public school returned after getting back on track.

Melissa Peddie enrolled her now 16-year-old, Jessie, in Gold Star after growing weary of battling for help with his anxiety disorder. She tried homeschooling but said she didn’t have the time or skill to do it well.

At Gold Star, she said, she could finally breathe again.

“They understood his needs. They were so tender and caring,” said Peddie, a paramedic. “He came home from school happy. He was a different child.”

Now Gold Star wasn’t a perfect fit. Jessie missed students his age. He wanted to play guitar in the school band. He wanted to be in JROTC.

So after two years at Gold Star, Jessie enrolled in the district high school.

This time, with his confidence restored, Jessie’s grades improved. Over the summer, he got an internship with the U.S. Forest Service.

Had Gold Star not been there, Peddie said, Jessie would have dropped out.

“I wish the world had a Ms. Janna and a Ms. Johnette to fight for their child. They were my guardian angels,” she said.

“Because of them, we’re going to make it through.”