The following bill has been filed for the 2022 Florida legislative session, which begins Jan. 11 and runs through March 11.

BILL NO: SB 1348

TITLE: Educational Choice Scholarships

SPONSOR: Sen. Manny Diaz – Hialeah Gardens

WHAT IT WOULD DO:

For more information, click here.

Kendrah Underwood, founding principal at IDEA Victory Vinik Campus, embraces a simple but profound philosophy: The proof of an individual’s success is the positive impact he or she can have on the lives of others.

Editor's note: reimaginED is proud to reintroduce to our readers our best content of 2021. This post from senior writer Lisa Buie originally published on Sept. 9.

In 2019, when she was teaching at Butler College Prep, a public four-year charter high school in Chicago, Kendrah Underwood earned the reputation as the world’s coolest teacher for filming a video of her students rapping about what they were willing to do to earn a good grade.

In 2019, when she was teaching at Butler College Prep, a public four-year charter high school in Chicago, Kendrah Underwood earned the reputation as the world’s coolest teacher for filming a video of her students rapping about what they were willing to do to earn a good grade.

The video, which attracted 5 million views in less than a week, looks like a well-rehearsed routine. But Underwood says the idea for it came to her a couple of days before filming.

“I’m a creative, think-outside-of-the box educator,” she told the Daily Mail after the video went viral. “I wanted to change the narrative of what the world continues to hear about Black students when it comes to education and positivity.”

Now, the former forensic science teacher has brought her philosophy to IDEA Public Schools, a network of public charter schools that serve more than 75,000 students at 137 locations. One of the newest is IDEA Victory College Prep in Tampa, Florida, where she is founding principal.

Underwood already is doing things in her own inimitable style.

Always looking for ways to inspire her students, Underwood organized a drum line to greet everyone on her school’s opening day.

She filmed a school tour this past summer in which she and her lower-school counterpart danced in their offices. On the first day of the new school year, she arranged for a drum line to welcome students as they stepped out of their cars and onto the new campus. (You can watch the video here.)

Underwood, an Atlanta native, is one of six sisters. She learned from her mother, who was a teacher, that “education was the one thing that can never be taken away from you.” Her mother’s “each one, teach one” approach to child rearing taught her “if one of us knew something or learned something, we had to teach our siblings.”

Though Underwood respected her mother’s profession, she did not want to follow in her footsteps.

“I saw how she worked so hard. Education shifted, and it changed. Before it had a lot more respect and prestige, but then it kind of went away from that. So, I had no aspirations of teaching.”

Growing up, Underwood wanted success, which she defined as a certain amount of money, a big, corner office and “just living the dream.” She considered several careers, among them becoming a lawyer.

She attended public district schools before heading to Agnes Scott College, a private, all-female college in metro-Atlanta. She earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology and anthropology and minored in Africana studies. After graduation, she earned a master’s degree in business administration and another in accounting and finance from American Intercontinental University.

Underwood’s first career job was as a sales manager for Cox Communications. She was a huge success and managed 250 auto dealer accounts in 72 cities. But it didn’t feed her soul.

“I found myself spinning my wheels and not living and working in my passion,” she said.

The experience she considers transformative was a church mission trip to Liberia and Ghana, where her group provided health care and helped train educators. She shared what happened on the trip in a presentation for Toastmasters International at Turner Broadcasting, where she worked as an employment paralegal.

It was during that trip that she found her calling to be a teacher.

“I was able to quiet my mind and listen to the purpose God had for my life,” she said.

In 2014, she joined Teach For America, a national nonprofit organization that works in partnership with 350 urban and rural communities across the country to expand educational opportunity for children. As a corps member, Underwood taught STEM to seventh- and eighth graders in Clayton County, Georgia, a southern metro Atlanta suburb.

In a series of videos for her forensic science students at her former school, Underwood encourages them to “follow the DNA” in a parody of a popular song by rapper Cardi B.

ADD PHOTO

Two years later, she headed for Chicago and Butler College Prep, where students are called leaders and a rigorous curriculum is offered that includes martial arts in addition to academics. She established a forensic science program and started creating motivational videos, including a parody of the Cardi B song “Bodak Yellow,” in which she and her students rapped and danced in white lab coats.

After working in traditional district public schools, Underwood says she prefers the freedom of charters, which are publicly funded but privately managed. Like district schools, they are tuition-free.

“I have worked in both, and (traditional district) schools are just different, and that’s all I’m going to say,” she said.

Two years after joining Butler, she was tapped to become an assistant principal at Success Academy, part of a charter school system that serves 23,000 mostly minority students in New York City who are outperforming students from the most affluent schools in the city and the state. She continued making headlines and using her famous videos as a teaching tool there.

Last year, when IDEA Public Schools announced plans to build two new campuses in Tampa, Underwood was tapped as principal in residence for Victory College Prep a full year before the campus opened in August.

She and Latoya McGhee, principal of IDEA’s Victory Academy, which serves elementary students, worked together to oversee the opening of the new school, one of Florida’s Schools of Hope, incentivized to locate near persistently low-performing district schools as an alternative for families seeking options. The schools promote a culture of “rigor and joy” and cite a 100% college acceptance rate in making their case to parents.

That same year, Underwood turned 40 and received her doctorate in education from Grand Canyon University in Arizona. The degree earned Underwood the nickname her colleagues and students use: “Dr. K.”

Underwood, who is mother to a middle school-aged son, says her experience as a parent has helped her be successful as an administrator because she can relate to families. The fact that she is doing what she feels she was called to do equips her to work long hours and deal with challenges that come up each day.

“If you are in your passion, it’s not work,” said Underwood, who credits her ability to do it all to “Black Woman Magic.”

Underwood might not have the corporate corner office or the big salary that comes with it, but she’s living the dream as Dr. K.

Founded in 1906, St. Mark’s School of Texas in Dallas is a nonsectarian, college-preparatory school for boys in grades 1 through 12. It is among about 900 accredited private schools in the state that serve approximately 250,000 students, according to the Texas Private Schools Association.

Texas, being a passionate, liberty-minded state, should be a national leader in school choice efforts.

Indeed, Gov. Greg Abbott, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, and the Republican Party of Texas all have called for an expansion of private school choice in recent years. Additionally, four Texas Democrats were listed as “School Choice Champions” by the American Federation for Children (AFC) in 2020.

But not only is Texas not a leader in parental choice efforts, it lags. This year, seven states created new school choice programs, while another 11 expanded existing programs. Several more are primed to join them.

Texas is not among them.

For more than a decade, an odd coalition of rural Republicans and urban Democrats, led by Republican state Rep. Dan Huberty, has stymied efforts to expand private school choice. Many of these opponents are homeschool advocates who fear government regulation or are rural public-school supporters who see anything beyond charter schools (and sometimes even charter schools) as a threat to community integrity.

Indeed, Texas deserves praise for its high-quality charter school network, but that network is no longer sufficient. Thousands of children are on wait lists, and Texas families are hungry for more and better choices they can access now.

Adding to that problem is the fact that many legislators have been squeamish for far too long, insistent on prioritizing the needs of school districts over the needs of students. Furthermore, there is no reason that school choice would suddenly limit what homeschooling parents can teach their children. There is no better time to expand school choice in Texas than the present.

Private school choice is incredibly popular with Texas voters. In 2019, long before COVID-19 was a consideration, an AFC poll found that 74% of Texas voters favored education savings accounts, while 64% supported tax-credit scholarships. With the pandemic’s chaos and learning loss now in clear view, one can only imagine what the support levels are now.

But there is a broader philosophical argument at play. Texas’ political culture is both individualistic and traditional. We care deeply for our families, traditions, and culture (don’t mess with Texas y’all), and education is fundamental in cultivating the virtues that make Texas, well … Texas. Love us or hate us, those qualities matter.

There is nothing more traditional or liberty-minded than putting parents in control of their children’s education. The presumption that governments and bureaucrats are better suited than parents to serve the needs of children is both absurd and un-Texan. Texas families deserve the same level of choice that families in states like Florida, New Hampshire, and West Virginia have.

The regular legislative session (and all its tendrils) may be over, but opportunities remain, a vital lifeline for families who are unable to wait for the next regular session in 2023. A growing number of legislators are clamoring for a special session to statutorily ban vaccine mandates. Under Texas law, the governor has the sole authority to call a special session and also is the arbiter of what will and will not be included in said session. Were Abbott to call another special session, he easily could include school choice measures as a topic of discussion.

Regardless of how change takes shape, Texas families need it now. They deserve the same breadth of options that children and families in other states have. One may call me naive for hand-waving the politics of the last 20 years away, but anyone paying attention can see where the winds are blowing. The parental choice movement is winning, both morally and politically.

It’s time for Texas to join the fight and expand school choice.

High on a throne of royal state …

Satan exalted sat, by merit raised

To that bad eminence …

-- Milton, Paradise Lost

I like the Garter; there is no damned merit in it.

-- Wm. Lamb, On the Order of the Garter

The English language – my native tongue – has its share of ambiguities. This comment focused upon the specific word “merit,” and only as it is deployed in the world of schooling. I claim no expertise beyond that of ordinary parent and lawyer who has, by chance, since 1962, been cast as critic of America’s “public” schools.

In my experience, most Americans express pride in being citizens of a “meritocracy.” Interpreting that term in a particular way (and with historical support) they have reason to do so; but, having lived so long in fickle times (b. 1929), I have come to fear that the term “merit” – as used in our schools – is not only ambiguous but often so in a subtle and potentially hurtful manner. Happily, this second, dangerous meaning can be identified and tamed.

Webster describes merit thus:

[S]omething that deserves praise or reward; commendable quality or act …

Note that Webster avoids any substantive meaning for the term. Merit is “something”; but just what makes it “deserved” is left unspecified.

The problem with our valuing “meritocracy” is a common tendency to equate merit with the use of brains and natural talent simply to achieve success at some legitimate career. Those among us who become billionaires, intellectuals, statesmen, star singers, scientists or the like get labeled “meritorious” because of some talent-based accomplishment in his or her brief moment on this planet.

Merit is something each has gained in the efficient use of natural smarts, beauty or talent – not necessarily in kindness and simple goodness.

In reality, of course, each can exist with or without the other. We fairly credit Colin Powell with both; but then there is the “meritorious” Nobel winner who corrupts teenagers.

Our tendency to deploy this word to label earthly success obscures and cheapens its mission to identify the “true” merit that is earned in obscure roles such as friend, parent or Good Samaritan to the stranger.

Allow me one more quote, this from Coleridge:

It sounds like stories from the land of spirits

If any man obtain that which he merits

Or any merit that which he obtains

-- The Good, Great Man

Coleridge may have overstated the problem. As a Boy Scout, I think I morally deserved at least some of my “merit badges.” But my later fascinating, mind-building assignment in the Army came by sheer luck and, in their classifications of curricula, assignment of individuals, and even the naming of schools.

Only promising, higher-performing students are admitted to programs dubbed “merit.” Particular schools even specify their basic admission criteria as “merit-based.”

Be clear; the substance of these policies and programs is not my concern here – only their labels. What does “merit” tell those who are rejected by that elite school or program? Is there a tag less dispiriting to the losers – child and parent?

Is it Pollyanna-ish to hope for labels less belittling, and perhaps more ambiguous? Would adjectives such as “experience-based” be such? What of the terms “skill,” “ready,” or “apt”? I concede the difficulty.

The problem with dethroning the “merit” words resides in the designing of parental subsidies for private school tuition (vouchers, etc.). Stephen Sugarman and I have designed specific model programs which would require participating private schools both to advertise widely their availability and reserve some fraction (say, a quarter), of all admissions for a lottery among “loser” applicants.

We have hoped, also, that “merit” and/or its cousins, such as “gifted” and “talented,” can be avoided in the entire admissions process. In any case, I would urge a continued effort to separate true human worth (and equality) from the halo of our natural and accidental gifts.

Empowered Minds Academy is an in-home microschool in Maricopa, Arizona, based on the Prenda model of 5-10 students led by mentors, or guides, who engage children in collaborative activities and creative projects.

Editor’s note: This post from Mike McShane, director of national research at EdChoice and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared Thursday on forbes.com.

The Roman philosopher Seneca is quoted as saying that “luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.”

When the coronavirus hit Arizona and parents were looking for options outside of their closed traditional public schools, they were lucky to find a proliferating network of microschools. But that lucky moment was years, if not decades, in the making.

In a new paper for the Manhattan Institute, I examine the phenomenon of microschooling in Arizona.

After hearing from several parents who found microschools to be a godsend after they grew frustrated watching their school boards and administrators dither and prevaricate on COVID policies, I wanted to answer a basic question: Why here?

To answer that question, we have to look back more than two decades into Arizona education policy.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Arizona pushed for greater school choice, with the legislature passing a charter school law and an open enrollment law, followed just a few years later by one of the nation’s first tax-credit scholarship laws. Over the intervening years, the state has created four more private school choice programs, including a nation-leading education savings account in 2011.

To continue reading, click here.

This opinion piece from Garris Landon Stroud, a Greenville, Ky., teacher and a Kentucky State Teacher Fellow, appeared recently on Education Post.

This opinion piece from Garris Landon Stroud, a Greenville, Ky., teacher and a Kentucky State Teacher Fellow, appeared recently on Education Post.

If I had a nickel for every time a school official uttered the phrase “unprecedented times” in the past year and a half, our schools wouldn’t need the American Rescue Plan.

But you know what isn’t unprecedented? Animosity towards those school officials and the systems they represent. And it’s heating up again, just in time for the holidays.

This time, the debate isn’t even over a specific critique of public education; it’s about who should be able to point out the shortcomings of school systems at all.

Does someone really have to be an educator to have an opinion on education? Because if you ask some of the teachers who chimed in, they’ll tell you that it’s classroom experience or bust. “This world has too many armchair quarterbacks,” one teacher argued. “Why not come get your hands dirty before you criticize?” another educator questioned.

And as fallout from this debate continues to occupy my timeline, I’m calling for a ceasefire.

The act of educating young people is a symbiosis between families and schools—a delicate and sometimes complicated dance. At the end of the day, schools are tasked with providing a service for students and families, which makes their satisfaction the ultimate charge. No school leader wants to deal with criticism, obviously, but this arrangement means that dissent should be fair game whenever it does arise.

In other words, if education is a public service, then the public should get a say.

To continue reading, click here.

Arizona Autism Charter Schools in Phoenix received a $2 million grant from A is for Arizona to improve student attendance and student retention, increase the number of families who have access to the program, and reduce transit burdens on families.

Parents increasingly are looking for more options for their child’s education beyond their local district school, a trend spurred by flagging test scores and politically divisive curricula. As a result, many are pulling their kids out of the traditional school system. Yet despite this enthusiasm for greater choice, logistical difficulties are preventing parents from improving their child’s education.

Parents, public policy scholars, and politicians in favor of school choice frequently have focused on legal regulations, resulting in much positive change. But even as districts have loosened restrictions, many parents still are practically unable to send their children to the school of their choice because they lack quality public transportation.

A new report from A for Arizona shows that lack of transportation is one of the driving factors keeping parents tethered to the local district. The “yellow school bus” system is strikingly outdated, serving fewer households than ever. Nevertheless, the school transportation system is massive, larger than any other mass transit system in the country.

Parents who lack the resources to drive their children to school must rely on this old-fashioned system, which poses an obvious problem: Local school buses travel only to the nearby school, effectively locking low-income parents into the local public school. This has significant ramifications for school choice.

Activists either can choose to focus on creating even more schools, or they can work to modernize transportation and extend the range of accessible options for parents.

School choice activists, who convincingly have advocated for the right to establish a greater diversity of schools, must not overlook school accessibility. One easy way local government can make schools more available to children of all socioeconomic backgrounds is to get out of the way.

Regulations on school vehicles, like whether charters must use a yellow school bus to drive kids to school, are stifling innovations; eliminating these rules would be uncontroversial and productive.

There is a role for local governments to play in the solution. Modernizing the logistical system would help parents and lead to more educational equity. Luckily, recent government initiatives show how state and local governments can give communities the practical resources to improve educational outcomes. One such example is Denver’s new “shuttle system”, which has attracted praise.

Arizona has also taken positive steps in this regard. Gov. Doug Ducey approved a $20 million grant program as a pilot to incentivize district and charter schools to propose solutions to the transportation challenge. Grant awardees for Arizona Transportation Modernization Grants recently were announced, and the proposals offer exciting and feasible solutions to local issues.

One grant was given to an Arizona rural district that gained many students through open enrollment. Their local public-school transportation “system” consisted of only one dilapidated bus, which made accommodating the influx of additional children difficult. The grant will support a school bus with Wi-Fi and other technological amenities so that these rural school children have internet access while completing the long rural bus route.

Other charter schools and local districts are using funds to authorize school vans, rather than buses, to increase the number of vehicles that can pick up kids.

These targeted policies that increase access to nearby schools are not trivial but genuine advancements for schoolchildren. The “micro-transit solution” proposed in Arizona could help many urban communities, and the idea is easily portable to districts across the country.

It is said that states are laboratories of democracy. This is a noble calling, and local governments should be willing to take chances to holistically improve their school systems.

School choice helps those financially and socially disadvantaged receive a high-quality education. Unfortunately, the poorest in society are the ones most affected by the government’s inability to provide adequate school buses. As parent Alysia Garcia told lawmakers:

“What is the point of having a great open enrollment policy if families aren’t able to utilize it? I’m fortunate to have a vehicle to transport my kids. What about the kids who don’t have vehicles?”

Transportation is not a glamorous issue. However, it is deeply important for the day-to-day lives of families. School transportation is a burden that will only worsen unless districts take active measures to change course. Longstanding problems have been left unaddressed, and many issues have been exacerbated by the recent bus driver shortage.

Local governments should work with school choice supporters to get serious about improving the transportation infrastructure around schooling. Focusing on improving access to reliable infrastructure will prevent students from being trapped in their local district school.

The desire for school choice has never been greater. Transportation limitations should not be the reason why a child’s education stalls.

Central Christian School opened in September 1965 as the fourth Christian school ministry in the state of Georgia. The school participates in the GOAL Scholarship Program, which extends educational opportunities to thousands of children through the state.

Editor’s note: This first-person essay from Georgia mother Desiree Williams was adapted from the American Federation for Children’s Voices for Choice website.

Desiree Williams and her son, Kyle

My name is Desiree Williams, and I am the parent of a 16-year-old named Kyle.

My son has been attending Central Christian School in Sharpsburg, Ga., since sixth grade. I learned about the school from a friend whose son was attending. She told me about Central Christian because she knew I was looking for a smaller environment for my son because I knew he would learn better that way.

I believe it is so important for parents to be able to choose where their children attend school, because all children learn differently. They have different needs, so a parent’s ability to have a say in their teaching environment is crucial to how and what they learn.

At Central Christian School, my son gets the attention he needs while following the basic class curriculum for his grade level while having the opportunity to participate in a college-bound program. Every student at Central Christian has the chance to take advanced classes to prepare for higher learning after high school.

Central Christian also offers a structured environment that teaches basic Bible reading and the word of God, which I feel is important, as it means students are less likely to avoid troublesome situations and make better life choices.

There are so many things that I love about Central Christian School. One aspect I particularly appreciate is the staff. The principal, the vice principal, and all the teachers are amazing. I can tell that this is not just a job for them, it is their calling. They are very passionate, God-fearing individuals that love each child. They go out of their way to make sure every child gets all the help they need to succeed.

Central Christian has an open-door policy that encourages parents to reach out at any time to talk about our children. The staff is very quick to answer any and all questions and address any concerns we may have. And volunteering is recommended, encouraged, and welcomed at Central Christian.

When I leave my child at Central Christian, I am comfortable knowing he is in a good environment. Knowing your child is learning and thriving, and exceeding expectations, is the best feeling in the world for a parent. It’s something every parent deserves, regardless of background and income level.

As a single mom, I have endured many struggles, physically and financially, to keep my son in attendance at Central Christian. School administrators have been a huge help, and I will be eternally grateful for their support.

The argument in Carson v. Makin is over Maine’s tuition assistance program, which pays for students in towns without a public school to attend another one of their choice — public or private — as long as it’s not religious.

This letter to the editor from Kirby Thomas West, a lawyer for the Institute for Justice who lives in Alexandria, Va., appeared Monday on washingtonpost.com. For additional context on Carson v. Makin, read reimaginED senior writer Lisa Buie’s post here.

In her Dec. 7 opinion essay, “Taxpayers should not fund religious education,” Rachel Laser claimed that the issue before the Supreme Court in Carson v. Makin is whether taxpayers can be forced to fund religion.

Instead, the issue is whether, if a state creates a school-choice program, it can bar parents from choosing religious schools for their children. Notably, no one in the case is arguing that states have to create school-choice programs — only that if they do, they must not discriminate against religion.

In 2002, the Supreme Court recognized that school-choice programs, because they rely on parental choice and are neutral toward religion, do not violate the establishment clause. Curiously, Ms. Laser failed to mention this well-established principle of constitutional law.

(Or that school choice programs, including religious options, have been the norm for decades, including in D.C., with none of the “religious coercion” parade of horribles she warns about.)

Instead, Ms. Laser suggested that Carson could have a negative impact on state anti-discrimination laws that protect LGBTQ individuals. But such laws aren’t at issue in the case, which is evidenced by the fact that even if a school welcomes LGBTQ students, Maine says it need not apply to the program if it provides a religious education. The only discrimination at issue in Carson is religious discrimination.

Ms. Laser apparently wants the court to perpetuate this discrimination. For the sake of parents seeking better educational opportunities for their children, let’s hope she’s wrong.

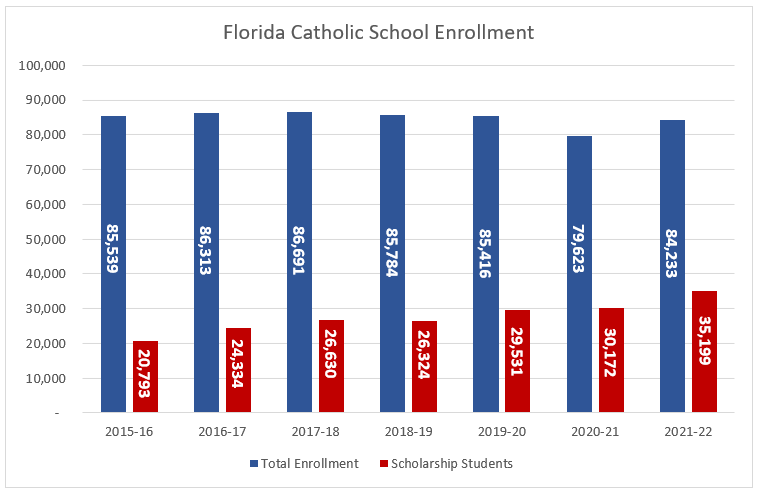

Catholic school enrollment in Florida rebounded this year following a nearly 7% decline at the start of the COVID pandemic.

Catholic school enrollment in Florida rebounded this year following a nearly 7% decline at the start of the COVID pandemic.

According to newly released data from the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, enrollment grew by 4,610 students, or nearly 6%, during the 2021-22 school year.

“Even though we experienced a drop in enrollment in the first full year of the pandemic, we maintained relationships with our students and families,” said Christopher Pastura, Superintendent of the Diocese of St. Petersburg. “When people felt safe again, it was natural for them to return.”

This year, there were 84,233 students attending Catholic schools in the Sunshine State, including 9,236 pre-kindergarten, or younger, children.

Except for a pandemic-induced dip in 2020-21, which rocked private school enrollment statewide, Catholic schools have remained relatively stable since 2015. Meanwhile, choice scholarship student enrollment steadily grew over the same time.

Except for a pandemic-induced dip in 2020-21, which rocked private school enrollment statewide, Catholic schools have remained relatively stable since 2015. Meanwhile, choice scholarship student enrollment steadily grew over the same time.

Scholarship students made up just 24% of Catholic school enrollment in 2015 but make up 47% of enrollment today. More than 75% of scholarship students (26,747) were on an income-based scholarship, while 13.4% of students (4,731) utilized a scholarship for children with special needs.

Florida is home to 237 private Catholic schools, with 222 enrolling students on scholarship. These Catholic schools employ more than 7,000 educators.

The Diocese of Miami is home to the largest concentration of Catholic schools and students with 63 schools and 32,412 students. Pensacola/Tallahassee is the smallest with 14 schools and 3,539 students.

According to the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops, 9.1% of students are Black and 44% are Hispanic. Eighty-two percent of students identify as Catholic, while 18% identify as non-Catholic.