Wondrous the stone of these ancient walls, shattered by fate.

The districts of the city have crumbled.

The work of giants of old lies decayed. —The Ruin

During the eighth or ninth century, an unknown author is thought to have surveyed the Roman ruins in Bath, England. The author composed an elegy in Old English, starting with the above lines. Today we know the poem as The Ruin. In the future, 2022 will be remembered as the year where we learned the ruinous academic consequences of the COVID-19 shutdowns on American schoolchildren.

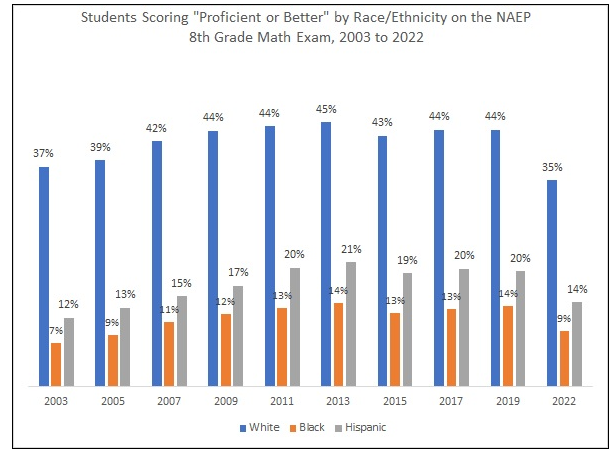

Since the publication of the A Nation at Risk, Americans have been furiously buying various ACME legislative products in the hope of both improving the quality of K-12 education overall and of closing the achievement gap between White and Black students. The NAEP exam results released this year reveal we have little to show in aggregate for our efforts:

The above numbers should be put into context. Equating studies between international exams and NAEP had about half of students in high-performing nations and states like Japan and Massachusetts respectively scoring at the “proficient or better” level on NAEP. Given that Japanese students attend after school “cram schools” and Massachusetts is a demographically advantaged state with a reputation for effective schools, I’m inclined to view any expectation of 100% NAEP proficiency as unrealistic.

I’m more interested in how progress and fate (more our own ineptitude) began crumbling progress approximately a decade ago, as you can see in the above chart. Students of all three race/ethnicities peaked on either the 2011 or 2013 exam, but results have been sliding since. There is not much Japan or golden-age era Massachusetts to be found in the 2022 results.

These mere numbers speak to great human tragedy, unrealized potential, a poorer future. The public education system, like the structures in Bath, won’t be going away, but our progress and the futures of a great many young people have been ruined. Awash in unspent federal money, school districts continue struggling to perform tasks as straightforward as running mere bus routes.

More complex tasks, such imparting literacy, numeracy, and civic knowledge, have also been going poorly and have worsened over time. American parents and grandparents should make their plans accordingly.

I recently published a white paper on K-12 funding equity in Arizona. The news was not great.

I recently published a white paper on K-12 funding equity in Arizona. The news was not great.

Back in 1980, Arizona lawmakers were concerned about a Serrano vs. Priest-style lawsuit from California (won by education choice icons Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman, by the way!). The lawmakers went and did what the plain language of the Arizona Constitution requires, equalizing public school funding.

It didn’t stick, so today, 61 of Arizona’s 207 school districts spend twice as much or more per-pupil education as the lowest-funded district. Charters receive less on average than district students per pupil, and students are not funded equitably across schools in the same district.

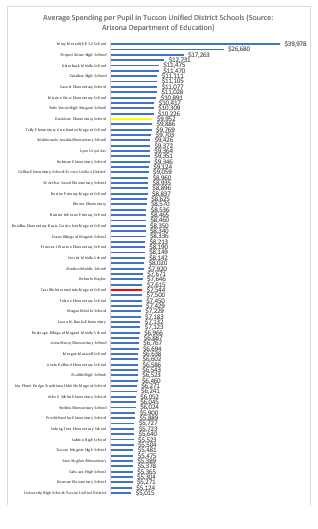

For example, Tucson Unified:

Don’t focus on the top of the chart (the top two lines are unusual), but rather, at the bottom. Every Tucson Unified school above the red line received 50% or more funding per pupil as the lowest funded school, and every school above the yellow line received twice or more per pupil funding than the lowest funded school.

Don’t focus on the top of the chart (the top two lines are unusual), but rather, at the bottom. Every Tucson Unified school above the red line received 50% or more funding per pupil as the lowest funded school, and every school above the yellow line received twice or more per pupil funding than the lowest funded school.

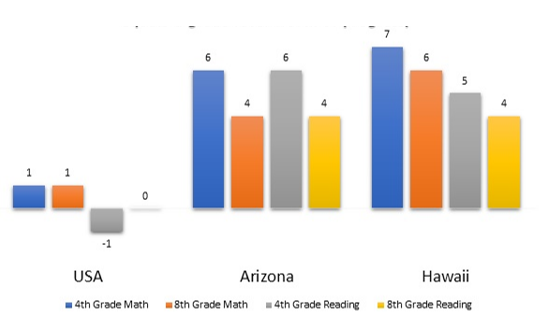

Hawaii funds schools in such a way that would make these sorts of inequities impossible. Lawmakers implemented weighted student funding during the 2006-07 school year. Between 2007 and 2019, Hawaii doubled or tripled the national average for progress on the four main NAEP examinations (fourth and eighth grade Reading and Mathematics).

While it is impossible to prove that weighted student funding was the sole, or even primary, cause of this level of improvement, a general trend toward decentralization seems to have served the state well. As shown below, Hawaii’s improvement on NAEP approximately equals that of Arizona during the 2007-2019 period.

In defying a general trend of malaise in achievement seen nationally, both Arizona and Hawaii seem to be doing something right. Interestingly, they seem to be doing different things right.

NAEP GAINS by subject, 2007-2019 for USA, Arizona and Hawaii

Hawaii’s academic gains could be of particular interest to Arizonans, because if they were induced by policy change, it is a possible source of improvement that Arizona has yet to adopt.

The state of Hawaii operates as a single school district, and also has a relatively modest charter school sector. While Hawaii ranked last in a 2020 study among states for K-12 parental choice, Arizona ranked first. State rankings in this study had a positive impact on academic gains. States with greater options for parents had statistically significant gains relative to states without it, all else being equal after controlling for other factors.

In Hawaii, however, it seems that all else was not equal. Hawaii has achieved respectable academic gains in a fashion different from Arizona. Yet Hawaii’s reform strategy is not mutually exclusive from Arizona’s. In other words, Hawaii could open more charter schools and pass private choice programs and Arizona could adopt weighted student funding.

Florida, by the way, also has a law on the books called the Equity in School Level Funding Act that prevents the sort of funding inequities seen in Tucson Unified. The law requires districts to allocate 90% of their funds to campuses as a whole, the “central office” thus employing up to 10% of funds, but no more. It also requires that no individual school receive less than 80% of their formulaic share.

Additionally, it Includes local rather than solely state funding, a crucial element in many districts heavily funded by local property taxes, such as those in Florida and Arizona. Such a provision in Arizona statute would make it illegal for the district cited above to fund a school at a $5,015 per student level, setting a floor for a minimum level of funding per campus.

The act also allows school principals to carry over funds year to year at the campus level without having them revert back to the district. This provision encourages school leaders to consider opportunity costs and avoids a “use it or lose it” perverse incentive, which creates a powerful incentive for administrators to spend money on almost anything rather than lose it entirely. But with carry overs, school administrators have the incentive to engage in longer-term planning.

A quick perusal of funding per pupil between campuses in Florida reveals that this act either has some sort of loophole or it is being routinely ignored. Perhaps Florida should say “Aloha” to funding equity as well.

A bill that would create education savings accounts that participating families could use for private school tuition, homeschooling or other educational expenses passed Georgia’s House Education committee Thursday.

A bill that would create education savings accounts that participating families could use for private school tuition, homeschooling or other educational expenses passed Georgia’s House Education committee Thursday.

House Bill 60 resembles legislation from previous sessions, most notably a school voucher bill introduced by Republican state Rep. Wes Cantrell. Cantrell and others have argued that such legislation would provide options to families whose children are not being served well at their district school.

“What this is about is helping the kids who are less fortunate,” Cantrell said last week. “They’re trapped in a cycle of poverty and an education strategy that’s not working for them for whatever reason, and it’s giving them a simple opportunity to have an option.”

Students from families making less than 200% of the federal poverty level – about $53,000 for a family of four – would be the first to receive eligibility, along with military families, students with disabilities and children in foster care. Next in line would be students in school districts that do not have an option for 100% in-person learning for at least a semester.

The bill proposes an eligibility cap of .25% of the state’s public school students for the first year, adding another quarter percent each year with a cap of 2.5%, or about 43,000 students based on current enrollment. A previous version of the bill allowed twice as many students.

Republican state Rep. Ed Setzler observed that school districts where students take advantage of an education savings account would see more money overall, and that while state money would go to the private school, the share of funding from local taxes would remain in the district.

“If students in your district use this program, this program actually lines the pockets of your district,” he said. “This program actually increases the per-pupil funding of the kids in your district who do not take this program.”

The bill needs approval by the full House to move forward.

![]() The performance of American public schools was in decline before the pandemic struck; based on the latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress released Wednesday by the National Center for Education Statistics, things are likely to only get worse from here.

The performance of American public schools was in decline before the pandemic struck; based on the latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress released Wednesday by the National Center for Education Statistics, things are likely to only get worse from here.

The data show the average reading score for the nation’s 12th-graders declined between 2015 and 2019. Meanwhile, there was no statistically significant change in 12th-graders’ average mathematics score for the same time period.

Bottom line: considerably more money per pupil was spent to get the same not-so-great results.

The tests upon which the data is based were given in spring 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. The indications are now worse: Inflation-adjusted spending per pupil is up, childhood poverty is down, and scores are down rather than flat.

The earliest 12th-grade reading score in this series comes from 1992. The Class of 1992 benefited from a nationwide average of $105,560 in 2018 constant dollars spent on their K-12 education. The Class of 2017, the cohort from which we have the most recently available data, had a nationwide average of $158,431 in constant dollars spent on their education – approximately 50% more. The figure for the Class of 2019 will be even higher.

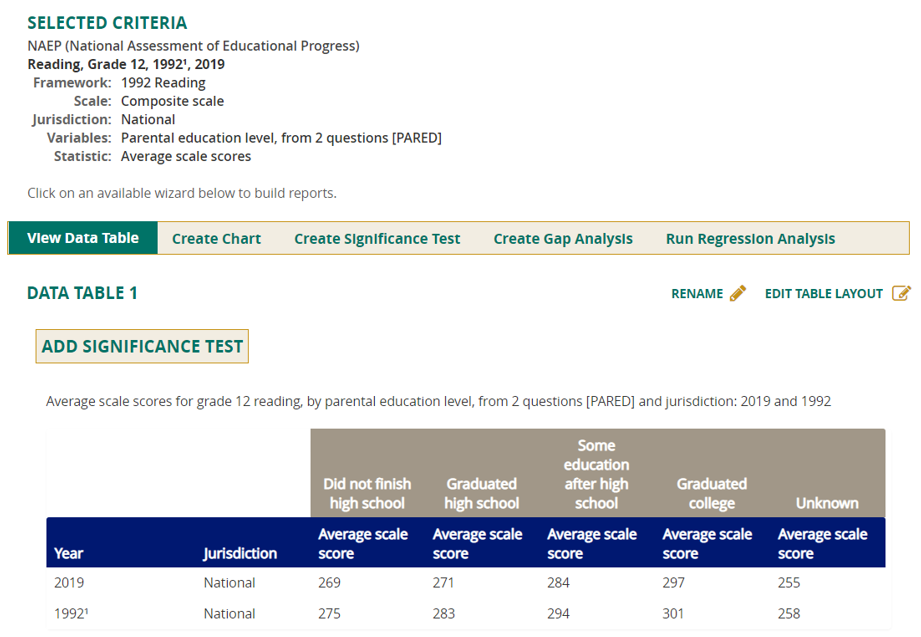

Which class, 1992 or 2017, demonstrated better reading ability? Let’s break down the results by parental education.

Regardless of the level of a parent’s education, reading scores were lower for the Class of 2019 than the Class of 1992. All of the above differences are statistically significant.

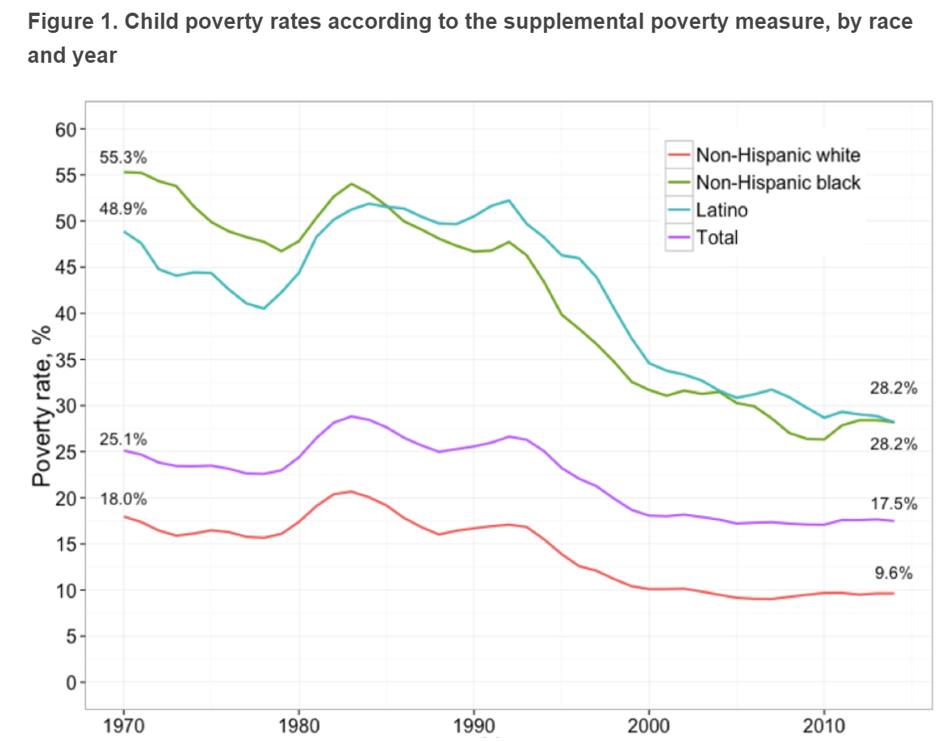

Now take a look at the chart below, provided by Michael J. Petrilli from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, showing the decline in childhood poverty rates from the 1980s and 1990s.

What the chart shows: higher spending, less poverty and lower national achievement.

Mind you, this was the trend before the current massive decline in instruction time due to the pandemic. I’ll dare to predict that if the NCES manages to conduct the scheduled 2021 NAEP, exams scores will decline across the board and achievement gaps will grow. K-3 kids who are in their literacy acquisition windows, for instance, in districts like Los Angeles Unified, Clark County Nevada and New York have been receiving less than half the amount of instruction time delivered during a normal school year.

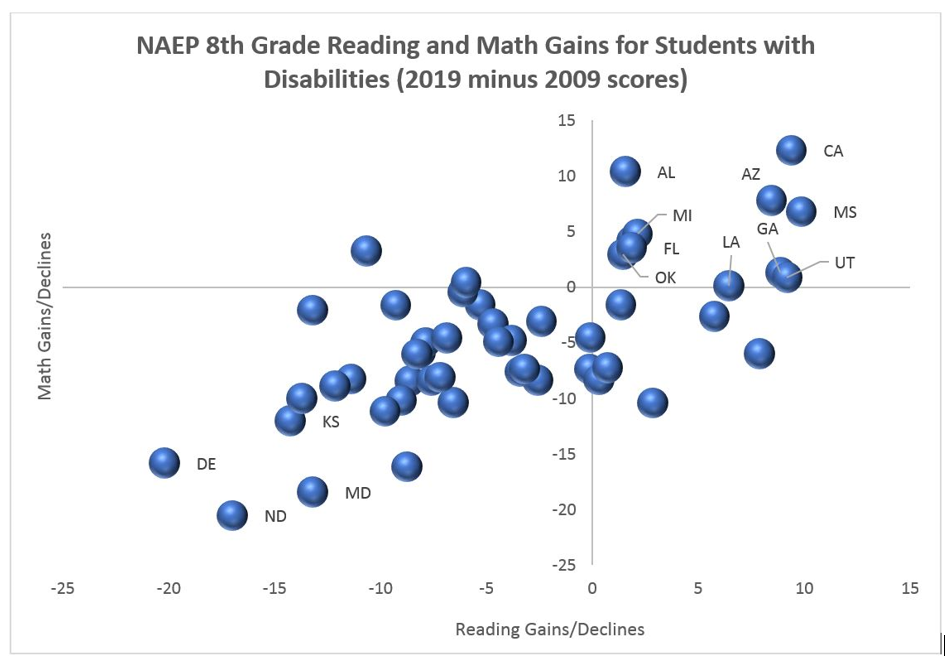

And finally, special education trends were a disaster in many states before the pandemic, as detailed in this chart.

It’s difficult to imagine that this already dismal chart won’t look even worse with 2021 data, coming in the aftermath of generally reduced instruction time and special education being attempted using the Zoom platform. We are not out of the pandemic yet, but the academic damage seems likely to greatly outlive the virus.

These most recent data came among favorable conditions of declining poverty and increased spending. Very soon, we’ll be forced to face what happens when you reverse these favorable trends and we end up with a large percentage of students with huge academic deficits.

Buckle up.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwalbach, a research assistant at The Heritage Foundation, first published on The Daily Signal.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jude Schwalbach, a research assistant at The Heritage Foundation, first published on The Daily Signal.

When COVID-19 brought the school year to an abrupt halt early this year, few anticipated that the global pandemic would be the impetus for private school choice reforms across the nation.

As is the case with so many other sectors, many private schools struggled after losing tuition and other funding resources due to the strains of COVID-19.

In fact, the Cato Institute reported that as of this month, 115 private schools had announced permanent closures.

That means that more than 15,400 children lost their schools. The estimated transfer cost of these students to public schools is more than $278.3 million.

Recognizing what the loss of education options would mean for families, policymakers in six states proposed emergency private school scholarships in response to the crisis. Four of those states—Florida, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Carolina—used emergency federal funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to expand private school choice options.

The CARES Act, signed into law by Donald Trump in June, authorized $3 billion for the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund, or GEER, a flexible grant that governors can use for education-related programs.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, used a portion of his state’s GEER funds to craft “Stay in School” scholarships, providing $10 million to cover tuition at Oklahoma’s 150 private schools for children from low-income families whose incomes have been affected by the coronavirus pandemic. More than 1,500 Oklahoma children could receive a scholarship worth $6,500 each.

That covers all or most of the average annual cost of private school tuition in Oklahoma, which is about $5,000 for elementary students and about $7,000 for secondary students. The scholarship amount, however, is still less than the average per-pupil amount, $8,778, spent annually by Oklahoma public schools.

Oklahoma students also will have access to the $8 million Bridge the Gap Digital Wallet education savings account-style funding, which is funded by GEER and will provide more than 5,000 children living in poverty with $1,500 grants to “purchase curriculum content, tutoring services and/or technology.”

In the era of pandemic pods, this is critical policy.

Likewise, South Carolina used its GEER funds to create a private school scholarship program for children from low- and middle-income families. Children living at or below 300% of the federal poverty line could be awarded a scholarship of about $6,500.

Other states used these funds to bolster existing private school choice programs such as tax credit scholarships.

New Hampshire under Gov. Chris Sununu, a Republican, boosted funding for the state’s tax credit scholarship by $1.5 million. The state’s tax credit scholarship allows individuals and businesses to receive tax credits for donating to nonprofits that fund private school scholarships.

Since 2015, New Hampshire’s tax credit scholarship has allocated $3.8 million to help 1,377 children attend private schools of their choice. The additional emergency funds will help 800 children receive scholarships valued at $1,875 each. That amount covers more than 22% of the average cost of tuition at a private elementary school in the state.

Like New Hampshire, Florida used $30 million of its GEER funds to stabilize its tax credit scholarship. At the same time, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, also put $15 million toward the Private School Stabilization Grant Fund. Private schools are eligible for this grant if they were hard hit by the pandemic and if more than 50% of the student body uses school choice scholarships.

Never missing a beat, special interest groups have alleged that efforts in those states to use GEER funds to support families accessing education options of choice will hurt public schools. Yet, public schools in Florida, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and South Carolina received a combined $1.1 billion from the CARES Act. Of that, the total governors’ discretionary funds accessible to children enrolled in private schools in the respective states totaled $96.5 million.

Taxpayers and state policymakers are right to balk at the new federal education funding. The $13.5 billion CARES Act, along with the $3 billion in GEER funding, is significant new federal spending, representing more than 25% of what the federal government spends yearly on K-12 education through the Department of Education’s discretionary budget.

But as The Heritage Foundation’s Jonathan Butcher wrote: “If the funds already are appropriated for education, as it is with CARES spending, then there is no more effective purpose than to give every child a chance at the American dream with more learning options.”

Moving forward, state policymakers should make sure that the emergency private school scholarships become permanent, funding them through changes to state policy. Rethinking how education funding is delivered, through more nimble models such as education savings accounts, should remain a permanent feature of the education policy landscape.

Moves in these states are steps in the right direction.

Editor’s note: Today, we offer Part 2 of a two-part post from redefinED executive editor Matt Ladner. You can read Part 1 here. Ladner’s commentary ends our series commemorating the 20th anniversary of the K-12 reforms launched by Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, collectively known as the A+ accountability plan.

One challenge to several of the A+ reforms is that they lack a natural constituency, which makes them politically vulnerable. The photo above is a good example of a natural constituency.

Not all policies, even worthy ones, necessarily animate people to appear at a state capitol in vast throngs. Bill de Blasio’s new administration, for instance, cast productive school grading and third-grade literacy policies aside without breaking a sweat and (lamentably) nary a murmur of protest. You can see what resulted when the mayor (who by his own confession “hates” charter schools) took them on here.

The most basic rule of politics is that organized beats unorganized every day of the week and twice on Sunday. Sadly, the folks who oppose most K-12 solutions – other than “hurl more money at the system and hope for the best” – have a high degree of political organization and engagement. They tend to have sympathetic allies working in bureaucratic agencies and commissions.

State law can attempt to compel them to do things but has a hard time compelling them to do something effectively. The families who have benefitted from state literacy policies or school grades largely are unaware of that fact, and thus do not constitute an effective constituency to defend or extend such policies.

The Florida Reading Scholarship, a recent program providing families with struggling readers funds to purchase services for them, might suggest a way forward. This program is relatively new and provides only a small subsidy -- $500 -- to students with a large problem (poor literacy skills). A primitive prototype version of this policy failed in an entirely predictable fashion when the No Child Left Behind Act funded the program through district budgets and left them in charge of program administration. You don’t need a Ph.D. in game theory to guess how that worked out.

You have to admit our technologies are getting better all the time. Now we can envision a supplemental services program that can interact with parents directly. Despite the many challenges that lay ahead in making the Florida Reading Scholarship program a success, a lack of a natural constituency would not be one of them. Onward.

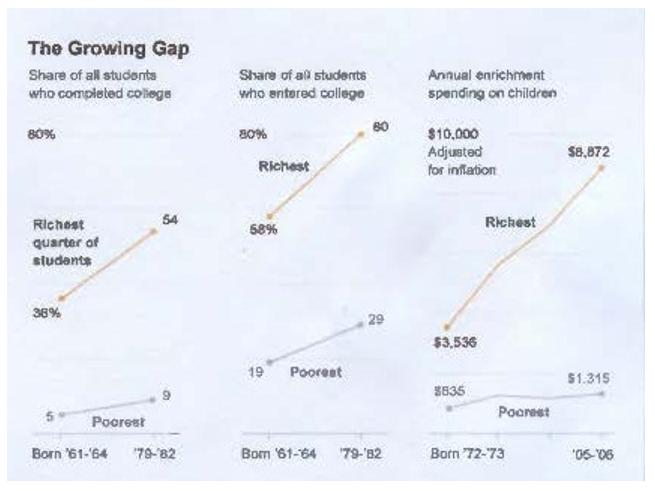

Upper income families have engaged in multi-vendor education out of their own pocketbooks with a growing frequency (see trend on the far right, below). This also seems to be working out relatively well on the outcomes side of things (see two charts on the left).

A $500-per-year scholarship for struggling readers is only a small step in attempts to address the glaring equity issue in the chart above. But the first step is the most important step, and once again, Florida is taking that first step.

Right about now, we don’t even know how much of the differences seen in education outcomes are the result of school effectiveness, or lack thereof, and how much is due to what we see going on in the right side of the chart. Put me down for some of both, but hopefully future research will give guidance.

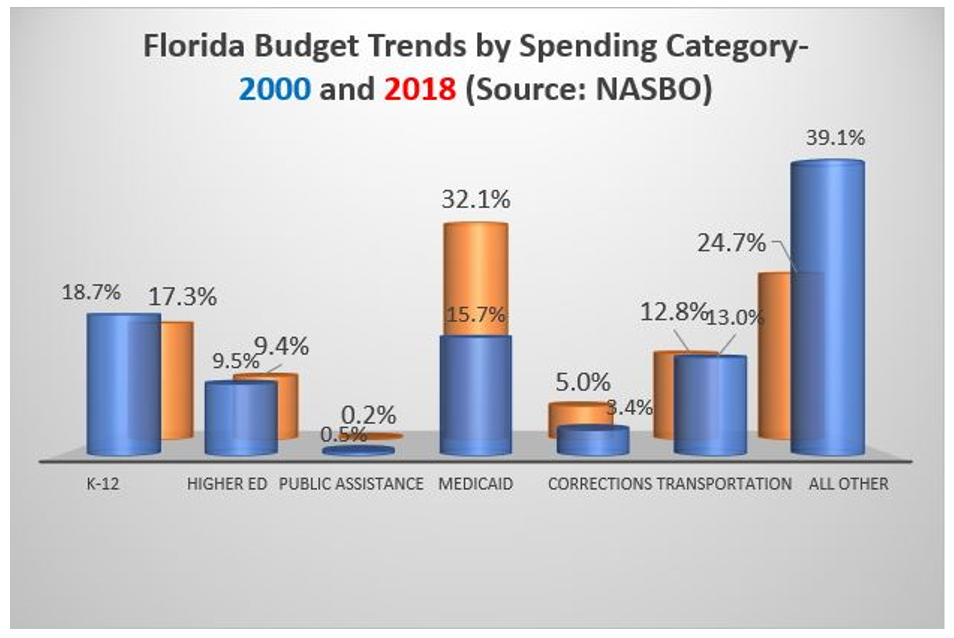

If you lived in normal times, you might think about working out the kinks to the Florida Reading Scholarship and going big with it if the results seemed promising. Just as a reminder however, the budget math looks unforgiving:

Grandma and Grampa Boomer already have called dibs on a great deal of expected revenue growth in the form of health spending; the middle of the chart indicates it’s already started. This means you’ll have to rely upon increases in the productivity of spending in the years ahead. Usually, this means adopting technologies to increase the productivity of labor, but this is easier said than done in the public sector.

Don’t feel overly daunted. Florida’s A+ plan increased the productivity of K-12 spending in a variety of ways after all. The young Florida adults in the early stages of their careers were far better educated than older generations. Florida’s public pensions are in relatively good shape. If you were, say, New York, none of this would be true, and you would have been spending approximately twice as much on per-pupil K-12 results and would not have gotten results as good as the ones you actually achieved.

So you need only increase the productivity of public spending in a politically sustainable fashion while the country struggles to cope with large imbalances in entitlement programs. Your ancestors had to stare down nuclear annihilation after defeating global fascism, which came right after the biggest global economic depression in human history.

See? It really is getting better all the time.

Don’t know much about history

Don’t know much about history

Don’t know much biology

Don’t know much about science books

Don’t know much about the French I took

“Don’t Know Much” by Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil and Tom Snow

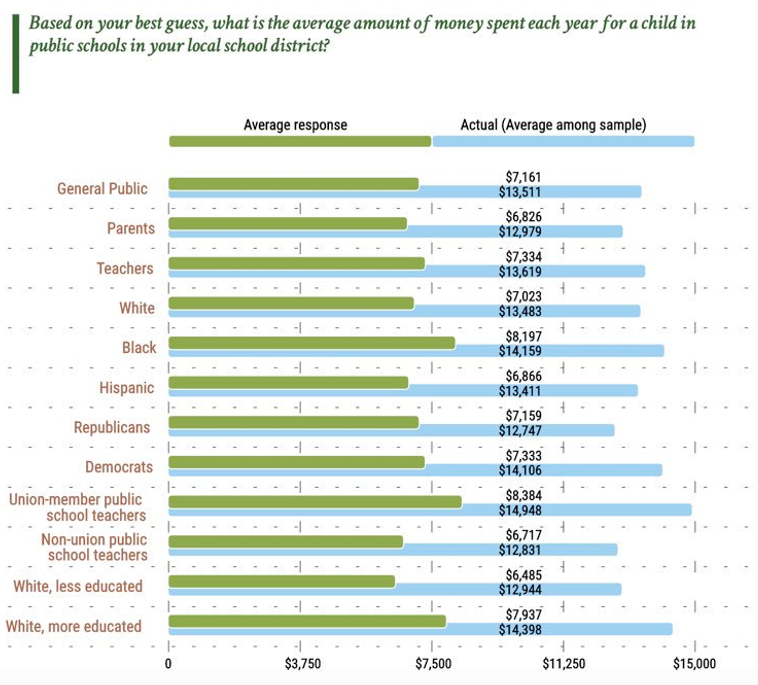

Education Next recently released its annual poll full of interesting information, including this graphic that shows Americans consistently underestimate the amount of money spent on public education in their state.

The upshot

The public is providing almost twice as much money per pupil as the average respondent estimates.

Why this is important

Results like these don’t mean we should spend less on public education. In fact, there are plenty of people who, when confronted with actual spending information, still want to spend more on K-12 education.

The results, should, however, compel us to take a moment to sympathize with the plight of the state lawmaker.

States don’t have a money printing press and generally deal with state constitutions that require expenditures to match revenues. The demand for expenditures always exceeds the supply of revenues, and the public’s demands are not, alas, consistently well informed.

Interestingly, the low-ball estimates for public school spending would be far more accurate if they were a guess as to state per-pupil spending on charter school students. These estimates would be higher than the average per-pupil funding received by students in private choice programs.

Where we should go from here

Pollsters frequently will produce polls that find “X percent of the public support increased funding for Y policy priority.” That’s all well and good, but if you are a lawmaker charged with the responsibility of passing a budget, you have no choice but to establish relative priorities – health care vs. higher education vs. transportation vs. K-12 education – and lots of other things within the context of available revenue.

So, the next time you talk to a state lawmaker, try thanking him or her for doing a difficult job before you complain about how he or she is doing it.

Johns Hopkins University’s School of Education on Wednesday released a 93-page report of the Providence, Rhode Island, Public School District that provides a useful cautionary tale on how not to structure a K-12 system, reminding us that big spending and strong unions fail to produce learning for kids.

Johns Hopkins University’s School of Education on Wednesday released a 93-page report of the Providence, Rhode Island, Public School District that provides a useful cautionary tale on how not to structure a K-12 system, reminding us that big spending and strong unions fail to produce learning for kids.

Among the report’s highlights:

· The great majority of students are not learning on, or even near, grade level.

· With rare exception, teachers are demoralized and feel unsupported.

· Most parents feel shut out of their children’s education.

· Principals find it very difficult to demonstrate leadership.

· Many school buildings are deteriorating across the city, and some are even dangerous to students’ and teachers’ wellbeing.

You can view local television coverage of the “devastating” report here and here.

Meanwhile, the Digest of Education Statistics shows that Rhode Island spent a total of $16,496 per pupil in the 2014-15 school year compared to Florida’s per-pupil expenditure of $9,962.

The John Hopkins researchers visited multiple Providence classrooms and found reading classes where no one was reading and French classes where no one was speaking French. They did, however, observe kindergarten students punching each other in the face, students staring at their phones during class, and students communicating over Facetime during class. One can only shudder to think what might be going on when university researchers aren’t touring the school.

Twenty-five kids in a Providence classroom will generate a bit over $400,000 in revenue. That money gets spent on something, but alas, there isn’t much learning happening.

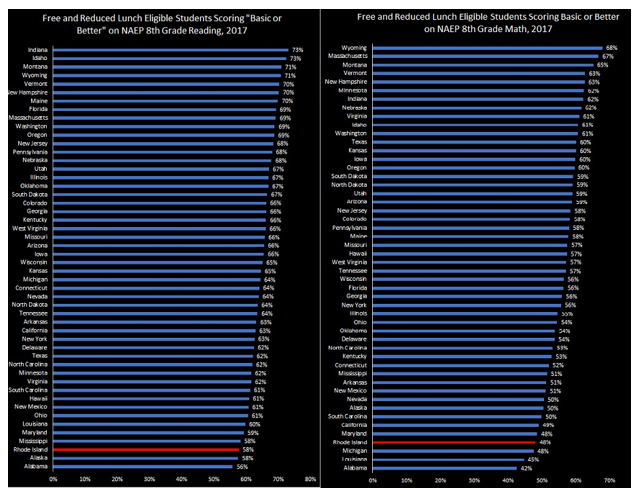

Now at this point in the conversation, some of our friends with reactionary traditionalist K-12 preferences often trot out the litany of poverty in the district. We can’t expect kids to avoid Face-timing in class overcome the burdens of poverty until X, Y or Z is done. Well, all states have low-income kids, so how does the academic performance of low-income students in Rhode Island compare to those in other states?

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores strongly reinforce the findings of the Johns Hopkins researchers. For those of you squinting at your iPhone, that is Reading on the left, Math on the right. The percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch who scored “basic or better” is shown on both charts.

These results are nothing less than sickening for Rhode Island, given the gigantic taxpayer investment in the system. Mississippi beats Rhode Island on both tests, and Rhode Island’s poor children score much closer to poor children in Alabama than they do to poor children in neighboring Massachusetts.

Florida is the only state with a majority minority student population to crack the Top 10 in either Reading or Math in 2017. It is unfortunate that a vocal minority in Florida seems desperate to kill the policies leading to that improvement, and hell-bent on adopting a policy mix closer to that of Rhode Island.

Those of us who are career educators know the veracity of the old saying, “Every education decision is a political decision.” This is especially evident in how school districts and their elected school boards distribute resources. In most school districts, affluent families with political influence have access to more and better resources than lower-income families with less political influential.

Those of us who are career educators know the veracity of the old saying, “Every education decision is a political decision.” This is especially evident in how school districts and their elected school boards distribute resources. In most school districts, affluent families with political influence have access to more and better resources than lower-income families with less political influential.

Teaching, for example, is the most valuable asset school districts distribute. Research shows that Inexperienced first-year teachers are much more likely to teach in high-poverty schools than in schools serving affluent families.

This disparity in political influence and resource allocation undermines public education’s mission of providing every child with an equal opportunity to succeed. This inequity is highlighted in a recent report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce called “Born to Win, Schooled to Lose.”

The Georgetown researchers examined the relationship between student potential, academic achievement, and family affluence and found that family affluence (i.e., income and social capital) has a greater impact on student achievement than student potential. Instead of promoting social mobility, these researchers found that our K-12 education system perpetuates class and racial inequalities.

The authors summarized their key findings as follows.

· “Our existing systems distribute opportunity based on income, class status, race, and ethnicity rather than hard work and talent.”

· “Among children who show similar academic potential in kindergarten, the test scores of economically disadvantaged students are more likely to decline and stay low during elementary, middle, and high school than the test scores of their high-SES peers.”

· “Family class plays a greater role than high school test scores in college attainment.”

· “Only by amending the inequities in our education system will we achieve anything close to equitable economic and social outcomes in society.”

These findings are not surprising. Public education has never been able to provide every child with an equal opportunity to succeed. And it’s not because people aren’t trying. The problem is systemic. Our current public education system isn’t capable of delivering excellence and equity no matter how hard our educators, parents, and students try, or how much money we spend.

We need a better system.

The education choice movement’s strategy for improving public education starts with giving low-income families more power. First, by giving them more control over their child’s public education funds, and second, by giving them more information about which education choices will most benefit their child.

The Georgetown report identifies unequal access to out-of-school learning opportunities as a huge source of inequality. The education choice movement concurs and advocates giving lower-income families Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) to help pay for some of the same afterschool and summer education programs that more affluent families enjoy.

We can’t reduce the achievement disparities in public education without first reducing the political inequalities that have their basis in race and class. The empowerment strategies being advocated by today’s education choice movement are a good place to start.

Doug Tuthill is president of Step Up For Students, which helps administer the nation's largest private school choice program (and co-hosts this blog).

The term “for-profit” has been weaponized in public education by teachers unions and their tribal allies.

They wield it against education improvement initiatives they oppose, especially education choice programs not covered by collective bargaining agreements. (Choice programs not operating under collective bargaining, such as Florida’s Voluntary PreK program, are not targets of for-profit attacks.)

For-profit corporations are forbidden to operate charter schools in Florida and California. Yet these schools are constantly being attacked for profiting off students. The overwhelming majority of Florida private schools serving tax credit scholarship and voucher students are non-profit, but newspaper editorial boards regularly criticize them for making profits.

These critics seem unfazed by the reality that district schools could not function without the products and services purchased from for-profit corporations. School buses, desks, instructional software, hardware, interactive whiteboards, books, pencils, pens, copy machines and paper are all purchased from for-profit companies. School buildings are constructed by for-profit companies using materials purchased from for-profit corporations. A proposed law requiring school districts to purchase products and services only from nonprofit organizations would be fiercely opposed by school districts, who would correctly see this as an attempt to destroy public schools.

Despite their for-profit criticisms, teachers unions rely on the profits they make from for-profit businesses to help pay their bills. During my tenure as a Florida teachers union leader, we sold insurance and financial services to teachers through various for-profit businesses. I still use a National Education Association credit card through a for-profit venture involving the NEA, MasterCard, and Bank of America.

The NEA’s for-profit businesses are not illegal. Nonprofits can own for-profit businesses provided the profits from those businesses are used for nonprofit purposes. My hometown paper, the Tampa Bay Times, is a for-profit company that is owned by the Poynter Institute, a nonprofit which provides professional development opportunities for journalists.

While teachers unions’ criticisms of for-profit businesses in public education may be disingenuous, ensuring taxpayers get the best possible value from education products and services purchased with public funds is important. But requiring that services teachers unions don’t like, such as charter schools, be purchased only from nonprofit organizations is not the best way to serve the public good. The best way is through effective contracting and oversight by government agencies.

When state government or a local school board purchases services, they should focus on maximizing the public’s benefits, not on the characteristics of the providers. As a taxpayer, I don’t care if a provider is gay or straight, male or female, black or white, for-profit or nonprofit. I want children to receive great services for a fair price. Focusing only on quality and price may not further the political agendas of certain advocacy groups, but it does serve taxpayers and the people receiving these services.

Determining what constitutes the best services for the best price is often challenging in public education. An afterschool tutoring program, a neighborhood district school, or a Montessori charter school may work well for some students, but not others.

The legendary management consultant, W. Edwards Deming, defined quality as customer satisfaction and not goodness, because what is good for one person may not be good for another. This is why parental empowerment and education choice are essential for helping determine what constitutes quality in public education. Empowering parents and educators to customize each child’s education is the best way to maximize the public’s return on its public education spending.

Given the proliferation and necessity of for-profit organizations in public education, attacking those that aren’t covered by teachers union collective bargaining agreements would seem a flawed political strategy. But it works with people and organizations who are part of the same political tribe as teachers unions, most notably many daily newspapers, Democratic politicians, and liberal advocacy groups.

As more low-income, minority, and working-class families participate in education choice programs, I hope teachers unions and their political allies will become more open to seeking common ground with these families. Many of these families are struggling to break the cycle of generational poverty. Hypocritical attacks on for-profit organizations providing services to school districts and state governments are not serving the greater good. We need to focus our collective energy on how to efficiently deliver educational excellence and equity to every child.