Autism Inspired Academy is an education-based nonprofit in Clearwater, Florida, that applies character education and social-skill development as the foundation of student growth. The school’s mission is to empower children with autism to have lives of meaning, purpose and joy.

CLEARWATER, Florida – Inside the walls of a sky-blue building surrounded with shade trees dwells a story of hope and inspiration and the shared dream of two women determined to help a special population of children.

For Liz Russell and Cher Harris, co-founders of Autism Inspired Academy, the school offers an opportunity to pour out their passionate commitment to helping children cope, grow, and one day make their way in the world. For their students, it’s a chance to face daily challenges and make slow yet measurable progress.

“When we were thinking of a name for the school, we started with Austism Aspiration, and then we changed it to Special Needs for Life,” Russell said. “But as we were going through the process, it dawned on me – the name needed to be Autism Inspired Academy because we are inspired by these kids every single day.”

Principal Cher Harris

The story of how she and Harris teamed up is as unique as the school they've created.

Harris, who serves as principal, had always loved working with kids and eventually found her calling in the area of exceptional student education at a Tampa Bay area elementary school.

“My first year I worked as one-on-one assistant to a child with many medical needs, but it wasn’t what I was looking for,” she said. “So, my supervisors came to me and said, ‘Why don’t you try working in a classroom for kids with autism?’ I really knew nothing about autism at the time. But after a few weeks in class, I was like, ‘I love this. I need to learn everything and know everything there is about it.’”

Harris delved into this new world, researching and reading books about autism, driven by a desire to become a teacher. She earned a bachelor’s degree at St. Petersburg College, which led to her first full-time teaching job. She quickly developed a natural gift for communicating with children for whom communication can be difficult.

In 2017, the local Council of Exceptional Children named her exceptional student education teacher of the year. She went on to become ESE teacher of the year for the state of Florida. By that time, she had earned a master’s degree in special education with a focus in autism from the University of South Florida.

When she started thinking of opening her own school for children with autism, she went back to college and completed a master’s degree in administrative leadership to learn how to run a school.

“I knew the behavior part and the autism part, but I wanted to learn the budget, the finance and business side of things,” Harris said.

Meanwhile, Russell’s journey was taking shape some 2,500 miles away. After earning a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Nevada Las Vegas, she completed a master’s degree in elementary education and another in counseling. She taught writing to eighth graders for five years, then went to work for a national faucet manufacturer, eventually becoming national sales manager.

During that time, her son, Gavin, was diagnosed with autism, and Russell, then a single mom, became his advocate. She attended conferences to learn all she could about the latest therapies and made sure Gavin’s school met his needs, visiting regularly with the principal and teachers.

“He was my ‘why,’” she said.

About a decade ago, Russell relocated to the west coast of Florida, and while searching for the best learning environment for Gavin, heard about an amazing teacher working wonders with children with autism – Cher Harris. Russell attended a few conferences where Harris was leading parent trainings and decided to enroll Gavin at the school where Harris worked.

“My gift is in finding excellence in people and then getting out of the way,” Russell said. “And I saw that excellence in Cher.”

Russell suggested they meet to talk about their shared love for children with autism. The seeds for Autism Inspired Academy were about to be planted.

***

Harris talked about her grand vision for a school at their first meeting, but Russell, drawing on her business acumen, suggested an interim step – a camp that would empower children with autism and provide summers filled with fun and purpose.

They agreed it was a sensible way to start, and Russell proceeded to visit youth centers throughout the area to find a site. The plan changed when a local youth center official suggested they look at the expansive, kid-friendly acreage of the Florida Sheriff’s Youth Ranch in the city of Safety Harbor, about 20 miles west of Tampa.

Many meetings later, the camp became a reality, with six children attending the first year. Three years later, with support from community partners, that number grew to 25.

“We learned early on that we had complimentary skills,” Harris said. “Liz brings the business and sales knowledge and I have the educational experience. And we are both passionate about helping children with autism.”

Autism Inspired Academy’s low teacher-student ratios allow for small group and individualized instruction, along with focused learning opportunities.

As their venture flourished, the idea for a starting a school continued to percolate. Russell had remarried after moving to Florida, and both she and her husband, an attorney, were committed to providing the resources needed to get the project off the ground. They scouted possible locations, fell in love with a property in nearby Clearwater that housed a pre-school and after-care program, and bought the place.

They knew it would take time and effort to transform the buildings into a fully functioning school. Fortunately for Russell and Harris, they crossed paths with the chief executive officer of a private school program specializing in serving the needs of children with various challenges, including autism.

He believed in what Russell and Harris were trying to do and told them about the Drexel Fund, a nonprofit venture philanthropy group based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that seeds new school models, scales up existing schools, and works to create the market conditions necessary for new private schools serving low-income students to thrive.

Russell and Harris applied for a grant and were awarded $100,000. The money was a godsend, allowing Harris to leave her job and begin planning the new school with Russell full time. It also allowed Harris to visit schools across the country for children with autism to learn what worked well for them.

Construction of Autism Inspired Academy began in 2019. While the work was under way, the CEO who had told Russell and Harris about the Drexel Fund invited them to bring a group of 11 students to his school for a pilot program, so Harris began driving the students and a teacher there every day in a van, two hours roundtrip. Then the pandemic hit in March 2020 and construction came to a screeching halt. The students had to transition to online instruction like students all over the country.

“Basically, in two weeks, Cher developed a program for the kids and involved all their parents,” Russell said. “And two of our teachers, Toni Salvatore and Chloe Hoffman, implemented it beautifully. I was in awe.”

The new school was halfway completed by January 2021 and opened to 29 students as construction continued on the other half. In August, 55 students in kindergarten through eighth grade embarked on a bold new learning experience.

***

One month into the new school year, Autism Inspired Academy is filled with students, about 40% of whom are from lower-income families. All of those students attend on state scholarships for children with unique abilities administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog. Meanwhile, occupational and language therapists and committed teachers and staff support the mission of the co-founders: to help autistic children lead lives of meaning, purpose and joy.

That’s a formidable task considering autism covers a wide array of issues, which, according to the Centers for Disease Control, affect 1 in 54 children in the United States. Autism impacts social skills, verbal and non-verbal communication and behavior, with functioning ranging from highly skilled to extremely challenged.

The academy customizes instruction and support to meet each child’s needs. Students work on reading, do sensory exercises, and learn to stay in control of their emotions and reactions. Color-coded “zones of regulation” are marked with red and green tape to help students learn how to regulate their actions. Behavior that lands a child in a red zone is addressed so he or she can return to a green zone. Students are taught there are no “bad” zones, just learning opportunities for better choices.

Muted lighting, alternative seating options and limited visual distractions are just a few ways Autism Inspired Academy maintains a flexible space where students feel comfortable and safe so they can focus on learning.

Classrooms feature muted lighting and soothing music. Some areas are sectioned off to allow students to work quietly, reinforcing their ability to work independently. Behavior specialists, hired from among a half-dozen companies that support the school, accompany some students. In one middle school class, a fluffy Bernedoodle support dog named Frankly – a cross between a Bernese mountain dog and a poodle – engages with students. After the children complete their assignments, they are entitled to 15-minute “brain breaks” to give them a chance to play with other kids or by themselves.

A common thread that runs through each day is an emphasis on encouraging social interaction.

“Social skills are taught in every class and at every level,” Harris said. “That’s one of the big things – how to focus, share with a friend, stay seated in a chair.”

Among the children who are finding success at the academy is Jacki Craig’s son, Noah, who was a student of Harris’ at her former school. Craig credits Harris as being the best teacher her son ever had. She and her husband had relocated to Georgia for a job opportunity, but when they heard about Harris’ new school, they decided to move back to Florida.

“We came back so Noah could be here, and he’s thriving,” Craig said. “That’s how much Ms. Harris means to us and so many parents and students.”

It’s all part of the magic that Harris and Russell have created at their growing academy, inspiring students who, in turn, inspire them.

Compass Academy in Conway, Arkansas, is a private, non-profit school for children with developmental disabilities or those with difficulty adjusting to a public school setting. It provides full-time, year-round education for students age 5 and up and participates in the state’s Succeed Scholarship Program.

Like many parents of a child with special needs, Erica Boucher was frustrated at the lack of educational options available for her son Hayden. Diagnosed with autism, Hayden was labeled a “bad child” by school administrators who concluded that his difficulty in the classroom stemmed from Boucher not disciplining him enough.

The former preschool teacher and mother of five was thrilled to learn that her home state of Arkansas participates in the Succeed Scholarship Program, which opens the door for students with learning disabilities to attend state-approved private schools. Boucher reports that Hayden’s behavior has improved at his new school, Compass Academy, and that he has begun to move forward academically.

Says Boucher:

At Compass, they know how to help students with autism and learning disabilities cope with their conditions. They don’t punish Hayden — they help him. When he has a stimming episode, they know how to help him calm down and then let him return to his desk. They understand when he has a hard day with autism and don’t hold it against him later. Every day is a new day.

Boucher recently told her story to Project Forever Free. You can read it here.

The longer students remain on Florida’s Gardiner Scholarship program, the more likely their parents are to spend money on curriculum, tutoring and specialized services, a new working paper finds.

The study, “Distribution of Education Savings Accounts Usage Among Families,” by Michelle Lofton of the University of Georgia and Martin Lueken of EdChoice, examines the spending patterns of families on the scholarship program over multiple years. It is the largest of its kind to date.

The Gardiner Scholarship, created in 2014 and named after State Sen. Andy Gardiner’s family, provides parents of students with special needs with a scholarship worth an average of around $10,000. It is set up as an education savings account (ESA) where parents can use the funds on more than just school tuition and fees. They also can purchase textbooks, school supplies, curriculum, tutoring, therapies and more.

The scholarship is currently limited to students with specific needs such as autism, Down syndrome and spina bifida. Last year, 17,508 students received a Gardiner Scholarship, with more than 9,000 enrolling in one of 1,870 private schools.

According to the researchers, family spending patterns change the longer they remain on the program. As families become more familiar with the program, they begin to spend more money on expenses other than tuition and fees, representing a desire to further customize their child’s education.

The study also finds rural families are more likely to spend the scholarship on curriculum and instruction than on private school tuition.

“These findings imply that families enrolled in ESAs are learning from prior usage and are able to customize education to areas beyond tuition over the course of their child’s educational life cycle,” the researchers wrote.

Since 2015, families have averaged 21 purchases, spending $8,373 a year. Usage increased from 60% of funds in 2015 to 88% by 2019.

Expenditures on tuition increased by 11%, or $550 over that time. But expenditures on instructional materials, specialized services, and college tuition savings plans increased considerably more -- instructional materials by 400%, or $1,375, and specialized services by 200%, or $450.

The number of purchases increased over time as well. In 2015 families averaged just nine purchases, but by 2019 families were averaging 30 purchases a year.

Spending varied by race and income as well.

Parents of Black and Hispanic students spent more of their scholarship, on average, than white students. They were also 7 to 9% more likely to spend the scholarship on school tuition than white students.

Parents in the top-quartile income areas spent more money on fewer items but spent less on tuition and more on tutoring and specialized services than families in bottom-quartile income areas.

The Gardiner Scholarship will become part of the Family Empowerment Scholarship for the 2021-22 school year, though the ESA component of the program will remain exclusive to children with special needs. Florida’s McKay Scholarship, a voucher program for students with special needs, will also merge with the Family Empowerment Scholarship in 2022.

Parents or guardians may apply for the scholarship here.

President Harry Truman famously opined that incoming president Dwight Eisenhower, a former five-star general, would have a rough go of things.

President Harry Truman famously opined that incoming president Dwight Eisenhower, a former five-star general, would have a rough go of things.

Observed Truman: “He’ll sit here, and he’ll say, ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen. Poor Ike—it won’t be a bit like the Army. He’ll find it very frustrating.”

State lawmakers attempting to boss around a vast sprawling field of public schools in their state bring this remark to mind.

I thought we had hit peak utopianism with No Child Left Behind legislation’s goal of 100% student proficiency by 2014, but then the Common Core project came along and instructed otherwise. Neither project ended well, and since 2009, American academic achievement has been in decline.

If lawmakers are on their A-game, they can create incentives and constituencies for improvement, but apparently the failings of the central planning strategy must be continually relearned. State lawmakers have a hard time commanding public school staffs to do things they aren’t keen on doing. Enforcement mechanisms are in short supply, and in the end, the door to the classroom closes and the teachers decide how to spend class time.

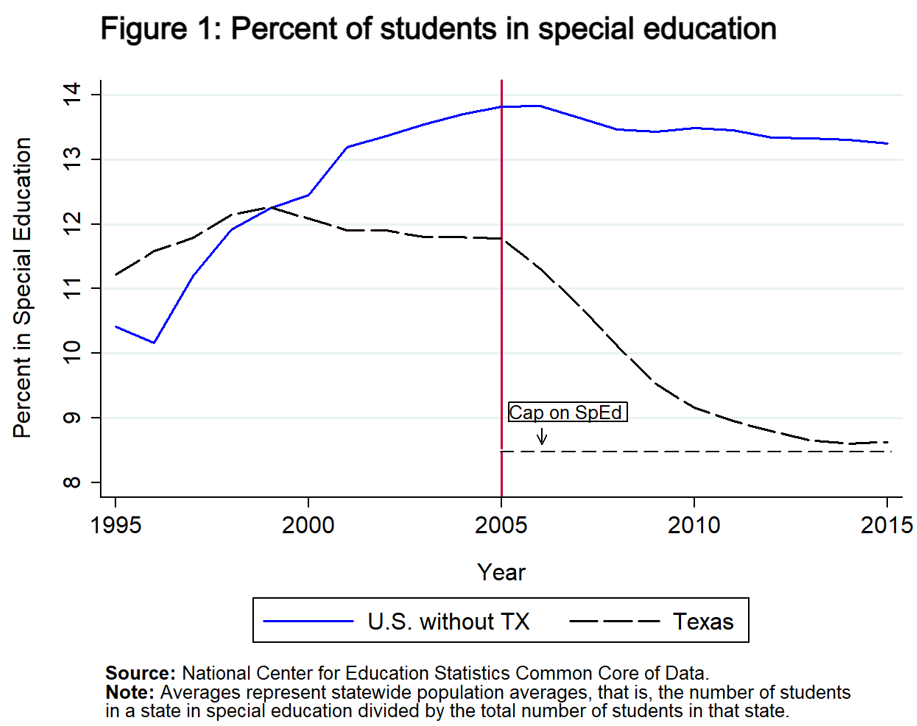

Things might be different, however, if officials in the capitol attempt to compel school personnel to do things they were kind of inclined to do, like when the Texas Education Agency covertly created incentives for public schools to provide fewer special education services. You can’t find evidence of creative or passive resistance evident in this new chart on the Texas cap from the Brookings Institute. Instead, we see rapid compliance:

Brookings has a new study on the Texas special education cap that features this chart. Without public hearings or legal authority, the Texas Education Agency created an entirely arbitrary cap of 8.5% of students in local education agencies (districts or charters) who should receive special education services. If your Local Education Agency served more than 8.5% of students (both the national and the Texas averages were much higher) the Texas Education Agency would audit and otherwise harass you to move you into compliance.

The agency separately created a covert standard on disportionality in special education rates between White and Black/Hispanic students.

Two things are horrible about the above chart. First off is the fact that this misbegotten policy ever existed in the first place, but second is how quickly compliance occurred.

While it is worth noting that some Texas local education agencies did provide more than 8.5% of students special education services, the statewide average for all public schools moved exactly to 8.5% before the Houston Chronicle wrote an expose exposing the practice in 2016.

The Brookings scholars tracked long term outcomes across student groups.

We find that, for students already in SE before the policy went into effect, the likelihood of SE (editor note: special education) removal increased by 13% as a result of capping overall SE enrollment. These reductions in SE access generated significant declines in educational attainment for previously classified SE students, who were 2.7% less likely to complete high school and 3.6% less likely to enroll in college. Lower-income students experienced even larger decreases in high school completion and college enrollment.

Texas schools stopped providing special education services to students at an accelerated rate, they then dropped out of school at a higher rate, and enrolled in college at a lower rate. Now for an entirely different type of horror, consider the second major finding of the study:

Black SE students more intensely affected by the Black disproportionality cap, we find increases in the likelihood of completing high school by 2% and enrolling in college by 4.6%.

Texas kicked Black students out of special education only to observe their high school graduation and college enrollment rates improve. If we are going to go with Occam’s Razor, it seems very likely that a great many of those students never should have been labelled in the first place. Which doesn’t speak well of our system of identifying students for special education services.

I would like to thank Florida’s former Sen. John McKay for pioneering the concept of a choice program for students with disabilities. The latest edition of the American Federation for Children’s guidebook listed 21 states with choice programs for children with disabilities, and new legislation passed this year.

Students in these states have not been entirely left to the tender loving care of a bureaucracy. Parents have options outside the public school system to see to the needs of their children. This is a fundamentally humane policy, and it should be employed everywhere – Texas more than anywhere else.

The central concept of federal special education law is to provide an “Individual Education Plan” for students with disabilities. This is, however, often hollow, and in the case of Texas, authorities charged with carrying out this charge instead covertly executed a plan to deny services.

The best Individual Education Plan is one in which you get to decide who provides services to your child. The worst sort of plans depend entirely upon what a bureaucratic system decides to give you.

Long-time education choice advocate Karla Phillips-Krivickas and her daughter, Vanessa

For 25 years, Arizona’s open enrollment law has allowed families to send their children to any public school they choose, even those outside their local school district. Yet open enrollment has remained out of reach for many students with disabilities.

That’s because while the state’s open enrollment law allows districts to establish and implement necessary policies, many of which guide efforts to determine capacity, these policies and capacity determinations are frustratingly limiting and opaque for the families of students with special needs.

Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey acknowledged this shortcoming in his 2021 Policy Book, saying, “The way we do open enrollment at school districts across the state is overdue for reform. It’s time to make it truly open for all.”

Lawmakers responded this year by introducing comprehensive legislation to remove obstacles families can face when seeking open enrollment and improving transparency in how districts determine capacity and approve applications.

The bill also specifically prohibits schools from limiting admission based on ethnicity or race, national origin, sex, income level, disability, English language proficiency or athletic ability. Correspondingly, schools will be prohibited from requiring the submission of any documentation other than that which demonstrates a pupil's age and residency. This includes any special education documentation.

Parents can — and will — select the best school for their child

Opponents of the bill argue that districts should be able to determine the services a student with a disability would need prior to admission. They claim the districts’ inability to preview all special education documentation is somehow a disservice to the child and family.

Unfortunately, evidence shows the disclosure of these materials has led to high rates of rejection for students with disabilities. It also furthers the idea that only the school administrators will know if a school is a good fit for a child, not the parents who requested enrollment at the school in the first place.

This idea presumes parent incompetence, something I personally find a bit insulting.

Parents know their children best. And since parents of students with disabilities have spent years advocating for their kids (often since birth), we are quite adept at researching and locating the services our students need. Moreover, the law is very clear that it is not the school that determines a student’s needs but rather an Individualized Education Program Team—which includes the parents.

The bill still allows school districts to establish a timeline for their open enrollment process with deadlines that allow sufficient time to determine all incoming student needs.

The bill’s opponents have voiced concerns of already diminished resources and shortages of critical personnel, but these problems are statewide, indeed nationwide, and the movement of students doesn’t change that. In fact, if a student moves into a district, the same dilemma exists, regardless of the student’s needs or how much advance notice the schools are given.

While there are shortages of many critical positions in education, it’s not — quite honestly — a family's problem to solve; nor is it specific to special education. And the parents of students with disabilities shouldn’t be the only ones asked to shoulder that burden.

Prioritize students, not programs

The bill specifies that enrollment capacity should be determined primarily by grade level. Though districts can calculate capacity for “specialized programs,” the legislation clarifies that these do not include special education programs.

This is important because districts are using “program” enrollment caps to reject the enrollment of special education students even when those students’ parents are requesting enrollment in a regular classroom and not a special program. The word “program” has never been questioned until now.

The “quality specialized special education programs” that experience limited capacity are segregated, self-contained classrooms. But most special education students spend the majority of their day in general education classrooms.

At the core of federal special education law is the priority of “least restrictive environment.” Under this policy, school districts are required to educate students with disabilities in regular classrooms with their nondisabled peers in the school they would attend if not disabled, to the maximum extent appropriate. Consequently, it is discriminatory for any school to presume placement in any type of program simply by a disability diagnosis.

And, at the risk of going too far into the weeds, I must point out that in special education, the term “program” commonly refers to the Individualized Education Program, not district-created, aggregated programs. As a result, it is impossible to determine capacity outside of anything but grade level.

All families deserve choice

Federal law is clear that special education is a service, not a place, and that programs are to be individualized. If Arizona is going to offer public school open enrollment, then it must be a real option for all students.

All we are asking for is equal opportunity under the law for our children.

Editor's note: Materials related to the study are posted to a landing page accessible at https://ceresinstitute.org/choices-and-challenges/.

Editor's note: Materials related to the study are posted to a landing page accessible at https://ceresinstitute.org/choices-and-challenges/.

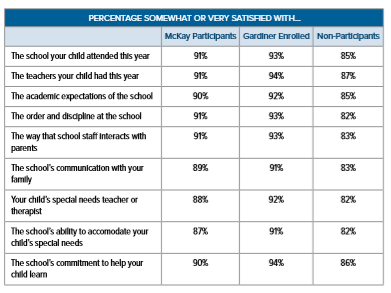

Nearly all Florida parents participating in two state scholarship programs for children with special needs are somewhat or very satisfied with their child’s educational experience according to a new study released today from researchers at Boston University.

The study from the Community-Engaged Research and Evaluation Sciences Institute for Children and Youth at the university’s Wheelock College of Education & Human Development reveals that more than 90% of families whose children receive the Gardiner Scholarship and the McKay Scholarship for Students with Disabilities cite transformative changes and benefits they perceive for themselves and their children.

Additionally, findings reveal, participating parents overwhelmingly recommend that the scholarship programs continue with modifications that would reduce barriers to accessing or fully benefiting from the scholarships.

The institute worked in partnership with the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas to answer two questions:

How do families who receive Gardiner and McKay scholarships navigate school choice and supplemental supports for their children?

How satisfied are parents with the scholarship schools they have chosen and the supports their children have received?

The mixed-methods research study, which entailed interviews with nearly 100 parents and included more than 4,000 survey responses, was conducted between fall 2020 and spring 2021.

Nine specific areas of parent satisfaction were measured, including academic expectations of the school, order and discipline at the school, and the way school staff interact with parents. For all measures, and for both scholarship programs, parent satisfaction was between 87% and 94%.

Based on the findings, the report’s authors recommend five considerations for statewide action to ensure that the existing scholarship programs are more widely accessible and more definitively equitable:

· Provide user-friendly, robust resources that equip parents to make informed choices, making the process for selecting and enrolling in a scholarship school simpler and more transparent

· Focus on creating more equitable access to information and services, addressing inequities in access to information as well as gaps between the cost of services and the amount of scholarship support

· Examine transitions between school levels, especially to and from middle school

· Continue to focus on improving accountability

· Give all parents of eligible students a real voice in the policies and practices that govern the scholarships

The authors note the Florida Legislature’s commitment this year of an additional $200 million to the state’s school choice program to expand eligibility and to merge the McKay and Gardiner programs into the Family Empowerment Scholarship Program effective July 1.

As that date approaches, the authors state, their report demonstrates the urgent need to provide eligible families with easy-to-access, consistent, high-quality information as well as a “supporting ecosystem” of other parents, educators, school leaders and scholarship-granting organizations to help families make the best choices for their children.

Nick and Keely Cogan are pictured at their Tallahassee home with their children, four of whom participate in the Gardiner Scholarship Program.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Nick Cogan of Tallahassee first appeared in the Tallahassee Democrat.

I’m a math professor at Florida State University. My wife Keely and I have seven children – three biological and four with special needs we adopted from China. Two have cerebral palsy, and two have Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita, a rare joint and limb condition.

All four are on the state’s Gardiner Scholarship, a flexible savings account that allows parents to spend their education dollars on the services such as school tuition, tutors, technology and curriculum that match their children’s unique needs. I don’t know where we would be without the scholarship. It has been a life-changer.

I believe all parents deserve the same opportunity.

Fortunately, a bill in the Florida Legislature would turn all the state’s school choice scholarships into flexible spending accounts like Gardiner. I hope it passes so more families can control their education dollars as they see fit.

We’ve used Gardiner for almost everything it’s been designed for. When we adopted our oldest son, Kai, he was an 11-year-old working on a first-grade level. It was hard to mainstream him. The public school district wanted to put him in fifth grade. Thankfully, we found a private school that was willing to put him with younger kids in a more academically appropriate environment. The Gardiner scholarship helped pay that private school tuition.

Later we decided to take Kai out of private school and homeschool him with his other siblings — Kade, Kassi and Karwen — who also attended a private school at one time or another. We rely on Gardiner to pay for books, curriculum, equipment and other educational supplies for all four kids.

Gardiner has made it possible for our children to receive the various physical and emotional therapies they require to develop. For instance, my daughter Kassi has made a lot of progress with her speech therapy. My health insurance covered only a limited amount of that therapy. Gardiner has ensured she gets the therapies that she needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been highly disruptive to education, and my homeschooled family has not been spared its effects. We typically participate in homeschool co-ops with other families, but those sessions have been suspended during the pandemic.

The Gardiner program gave us the means and the ability to swiftly respond to the crisis and direct our children’s education dollars into effective alternatives.

We bought pre-built curricula so we could have a consistent set of tools at home. These included some online resources and “workbook”-type resources. These have features for languages and math that offer dynamic feedback for students. We started a Duolingo classroom for the kids to learn Ukrainian (we are in the last stages of adopting two children from the Ukraine). The classroom option does a good job of tracking progress for us. We bought ours from a family-run business, which just shows the diversity of resources out there.

I am a strong supporter of public schools, but because of their special needs, our kids would not fit there. Gardiner gives us options that otherwise wouldn’t be available to us. That applies to other families as well, as each child has unique learning requirements. It's important to be able to customize education for each child.

That’s why I urge lawmakers to pass the bill that converts state scholarships to flexible spending accounts. The pandemic has showed that, now more than ever, families need as many options as possible.

Long-time education choice advocate Karla Phillips-Krivickas and her daughter, Vanessa.

In the two decades that I have been involved in the school choice movement, I’ve seen how choice policies can empower parents to select the school that best fits their child’s needs. But as the mother of a middle school daughter with a disability, I’ve also experienced the difficulty in finding a school that is the right fit. It’s even harder when you’re asked to make the decision sight unseen.

School policies v. FERPA

When deciding where to enroll my daughter for middle school last year, I was surprised when two schools said they did not allow parents of prospective or enrolled students to observe special education classes due to the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

This didn’t sound quite right. So, I called my state department of education and learned that the schools were, in fact, wrong. FERPA does not prohibit parents from observing their child in any classroom setting. FERPA guidance clarifies that the act "does not protect the confidentiality of information in general; rather, FERPA applies to the disclosure of tangible records and of information derived from tangible records."

But this reality doesn’t change the fact that some schools are denying parents the chance to observe classrooms.

Informed decisions

If prospective parents can’t observe classes, how will they know if the school’s programs are right for their child? Both schools told me that I should feel comfortable relying on their reputation and school letter grade since they are high performing schools. But that is so inadequate.

While discussing the unique challenges parents of students with disabilities face in school choice, researcher Lanya McKittrick appropriately noted: “ … the information that’s freely available might not adequately describe whether a school will be the right fit [for my child]—the only way for me to check out a school’s acoustics and lighting is to show up in person.”

Acoustics and lighting might seem inconsequential for some, but McKittrick’s youngest child is deaf-blind, and these details will make all the difference in her child’s educational experience.

Contrary to some schools’ policies, federal law and all related guidance encourage parent involvement, especially for parents of students with disabilities. If parents of enrolled students can’t observe, how can they meaningfully contribute to their child’s education and be full partners in the development of their child’s Individual Education Program (IEP)?

Not all parents are experts about special education, but no one knows their children better than they do.

State policy needed

I believe the solution to this problem is simple: States should require that every district and charter school adopt a policy, with parent input, for all tours, visits and observations that includes all classrooms or students.

Schools will, of course, need to find the best way to minimize distractions. Some situations may even call for observations via camera, windows, or other options. But all classrooms should be observable. Period.

Certain classrooms, of course, are specifically designed for students with significant emotional and behavioral disabilities, and some will argue that any observation would be simply too disruptive. To this I would respond with two simple questions.

First, if a parent is requesting to observe that classroom as a potential placement, isn’t it even more critical that they understand how the classroom functions—and how their student would fit in—before agreeing to the placement?

Additionally, we must consider that these students are often our most vulnerable since they typically have significant disabilities and may be non-verbal. Why wouldn’t we encourage frequent observations to ensure students are receiving an appropriate education?

Most schools value parents as equal partners in their child’s education, but some schools may need a push to enact valuable policies that allow observations and will, ultimately, benefit ALL educators, parents, and students. And it’s up to education leaders and policymakers to ensure this happens.

Because of the pandemic, parents have been able to observe and support their child’s’ virtual classes. The insights gained from these observations have only increased parent engagement and appreciation for educators. Let’s not sever that connection now when students return to in-person school. Let’s cultivate it!

Because no parent should be told—like I was—that they would have to decide sight unseen, trusting only the school’s reputation or past performance. These are our students. We know them, and we need to be able to make fully informed decisions to select the right education for them.

No Limits Academy in Melbourne welcomed 30 of its 44 students back to in-person learning last week. All No Limits students receive state scholarships, including about 70% who participate in the Gardiner Scholarship program.

After COVID-19 forced schools to shutter in March, many parents of students with special needs worried the shift to distance learning had shortchanged their children and caused them to lose ground.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention echoed those concerns in its recommendation for a return to in-person education. The American Academy of Pediatrics stressed the need for children with disabilities to have access to services that were challenging to deliver online. And in late July, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis held a roundtable at a school for special needs in Clearwater where parents expressed a desire for their children to return to brick-and-mortar education.

As school re-opening drew closer, parents continued to wrestle with the decision to send their special needs children back to school and risk their health or keep them home and risk academic regression.

No Limits Academy is maintaining its focus on academics for its students with unique abilities.

“Most of these kids were left behind,” said Laura Joslin, founder and CEO of No Limits Academy in Melbourne. The private, nonprofit school, located on Florida’s Space Coast, opened in 2008 and specializes in special education for students with unique abilities.

Joslin, the mother of two sons who have cerebral palsy, said she opened No Limits because district schools were unable to meet her sons’ needs. She also operates a rehabilitation center that provides onsite therapies for special needs students.

This year, Joslin offered her families a choice: Return to campus or learn at home using her specially developed virtual program. Most families chose in-person learning. Joslin and her team welcomed 30 of No Limit’s 44 students back to campus when school reopened last week.

All No Limits students receive state scholarships, including about 70% who participate in the Gardiner Scholarship program administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

Students eager to return greeted their teachers with smiles. “They were really excited to be at school,” Joslin said. “Life looks normal again.”

No Limits Academy is adhering to social distancing despite the challenge of making room for wheelchairs.

Not that the re-opening didn’t require major changes to promote safety. Teachers and staff are required to wear masks. Teacher, staff and student temperatures are taken upon entry to the building and throughout the day. No parents or visitors are allowed inside the building.

It’s not possible to require that students wear masks, Joslin explained, because many have respiratory difficulties or medical conditions. But other safety measures are in place.

Classes are self-contained with students staying with the same teachers and aides all day. There is a lot of handwashing and cleaning with medical-grade wipes. Students are socially distanced between each other as much as possible.

That presents a special challenge, Joslin said. “Wheelchairs take up a lot of space.”

There are other challenges. Many No Limits students need help with their most basic needs such as feeding, toileting and in some cases, diapering.

“I told the health department that if I have a child who needs to be changed, that’s not going to be 6 feet of distance,” Joslin said. “I’m trying to do the best I can with situation that I have.”

Despite the extra care required, Joslin stressed that education remains the primary focus at No Limits Academy.

The school maintains a routine that allows plenty of time for lessons. Students who are non-verbal communicate through devices attached to their wheelchairs. Students with vision challenges stay close to oversized message boards.

There are no grade levels at No Limits, only cognitive levels, and students advance as they master skills. They all have individualized education plans that specify their educational goals and necessary accommodations. Achievements, no matter how small, are celebrated.

“There’s no babysitting going on,” Joslin said. “What I want is brain stimulation.”

Although many parents insist on face-to-face education for their special needs children, Joslin says her virtual program is an equally valid choice. After translating her curriculum to an online platform in the spring to make a smooth transition for her families, schools in New York and New Jersey started contacting her for guidance.

Gavin McEver, 8, a student at No Limits Academy.

Tonya McEver said her 8-year-old son, Gavin, who has a chronic lung condition and cerebral palsy, is doing well with No Limit’s virtual program.

“I’ve heard about kids with special needs getting left behind,” she said. “That’s not happening here.”

Just two days into the new school year, McEver said, Gavin already had experienced a math, reading and vocabulary lesson, attending two sessions of classes in the mornings and one-on-one teacher sessions in the afternoons.

“We are blessed to be able to keep him home right now,” McEver said of Gavin, who spent six months in a neonatal unit after being born four months premature and weighing less than 2 pounds.

McEver turned to No Limits after Gavin came home from his previous school with bruises on his legs. The staff had restrained him in his wheelchair because he liked to be active while he learned.

She’s thrilled with the progress Gavin has made in just two years at No Limits.

“We see him engaging more in curriculum,” McEver said, adding that he has started communicating thorough a tablet.

“He was able to tell his teacher that his stomach hurt, and could he call his mom,” she said. “I was crying all the way to pick him up.”

This time around, they were tears of joy.

Karla Phillips, a long-time advocate for both school choice and inclusion, realizes she may need to change her personal and policy focus as she begins researching the best middle school for her daughter, Vanessa.

Editor's note: Today's post was written expressly for redefinED by education policy veteran and choice advocate Karla Phillips of Phoenix.

I love seeing new posts on the National Catholic Board on Full Inclusion Facebook page. It’s so encouraging to see the increasing number of schools welcoming students of all abilities.

But when I find myself daydreaming about my daughter perhaps becoming the first girl with Down syndrome to attend an elite school in our area, like Phoenix Christian or Xavier Prep, I have to stop and wonder—am I ready to be a pioneer?

Parents of students with disabilities take incredible leaps of faith when they enroll their children as the “first” in a school. Some make the choice because they are pursuing a faith-based education. Others may be driven to the decision because nothing else has worked for their child.

Regardless of the reason, these parents and their children are forgoing more traditional territory – district schools with formal programs, therapies, etc. – to become pioneers of inclusion and school choice. And that’s not an easy decision.

I have spent a fair share of my career fighting for school choice and supporting the efforts of state leaders to create as many opportunities as possible for students, especially those with disabilities. But now I am the parent and my daughter is the student. And we are faced with the decision of where to enroll for middle school.

When I was looking for my daughter’s first school six years ago, prospects were grim. More often than not, I was “counseled out” of the schools we were considering. We eventually found a wonderful school, but it wasn’t an easy task.

This time around, I’ve noticed a change.

More schools are willing to discuss the possibility of Vanessa enrolling. And while they would enjoy having Vanessa as a student, they’re not sure they’re prepared. A common refrain has been, “We have never had a child with Down syndrome.”

I often joke: “Neither have I.”

Despite their kindness, a message rings loud and clear: Many schools feel neither prepared nor equipped to welcome students with disabilities.

A new report from the Center for Reinventing Public Education examined how parents of children with disabilities choose their school. These parents reported similar experiences to mine. One parent explained that, “the lack of expertise is an urgent barrier for successful inclusion.”

In fact, CRPE’s new research uncovered a surprising truth:

“Having more choices without quality special education programming feels worse to families with children with disabilities than no choice at all, even if having more options makes the community as a whole better off.”

We’re told we have choices, but we feel like we don’t because schools aren’t ready to serve our kids. This isn’t what we have fought for.

I have spoken with some of the pioneers – parents of students with disabilities who have taken the leap into school choice – and their stories are often the same. The parents are either directly or indirectly finding the needed resources or services for their children.

The researchers at CRPE also found that “some parents had used their insurance or out-of-pocket funding to support their child, a potential barrier to educational access for some families.”

I have proudly pronounced myself an advocate for both school choice and inclusion, but I am realizing that I might need to change my personal and policy focus.

States are increasingly offering parents more school choice options. But for these choices to be truly viable options for all students, we need to identify ways to empower and equip schools and educators who will both welcome our children and help them reach their full potential.

Karla Phillips is senior director of policy for KnowledgeWorks, and with more than 20 years' experience, she is a seasoned veteran of education policy. As the mother of a daughter with Down syndrome, her passionate advocacy for all students has carried over into special education and disability policy. She is a graduate of Indiana University and received a master’s degree in public administration from Arizona State University. She lives in Phoenix with her husband and children.