In the classic Krisis at Kamp Krusty episode of “The Simpsons,” Bart discovers that the summer camp he and Lisa attend is a de-facto child slave labor camp, prompting him to lead a rebellion and camp take over. Decades later, your author still laughs uncontrollably when recalling the “Lord of the Flies” reference in this clip from the episode.

In the classic Krisis at Kamp Krusty episode of “The Simpsons,” Bart discovers that the summer camp he and Lisa attend is a de-facto child slave labor camp, prompting him to lead a rebellion and camp take over. Decades later, your author still laughs uncontrollably when recalling the “Lord of the Flies” reference in this clip from the episode.

Far less laughable is the emergence of reports from teachers concerning post-pandemic-return student behavior. A recent survey of public-school teachers conducted by The 74, a nonpartisan education news group, related:

From regular f-bombs and bullying to difficulty finishing assignments, raising hands or buttoning pants, young people across the country are struggling to adjust to classrooms after lengthy pandemic isolation.

One hundred twenty-two teachers from 37 states and Washington, D.C., painted a picture of a generation emotionally anxious, academically confused and addicted to technology, in a survey created by The 74 … Educators from coast to coast noted students had difficulty with common classroom routines — writing down homework, raising their hands to speak, meeting deadlines. And for the youngest learners, underdeveloped motor skills made it difficult to use scissors, color, paint, and print letters.

Kathleen Casey-Kirschling

Kathleen Casey-Kirschling, pictured here, was born at midnight on January 1, 1946, making her the first American Baby Boomer. She worked as a public-school teacher and retired (ahem) 15 years ago. All of America’s massive cohort of Baby Boomers will have reached the age of 65 by 2030.

No problem. We’ll just recruit Millennials to replace them, right? Wrong.

We saw declining success in the effort to replace Kathleen and her cohorts even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

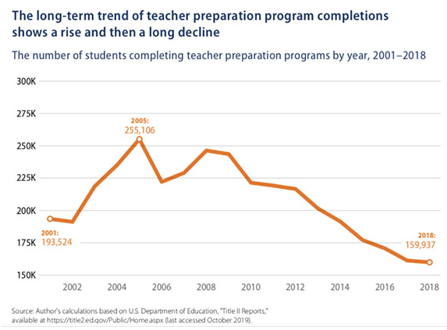

Ante-pandemic, the percentage of college students enrolling in colleges of education began to fall. During and after, the absolute numbers of college students began to fall, so let’s call that a shrinking percentage of a shrinking pool.

Ante-pandemic, the percentage of college students enrolling in colleges of education began to fall. During and after, the absolute numbers of college students began to fall, so let’s call that a shrinking percentage of a shrinking pool.

Lord of the Flies seems likely to simply reinforce the desire of college students to major in something other than education. With this context in mind, your author got a good, long chuckle from the absurd hysterics of Arizona passing a law to allow public schools to pay student teachers.

Said Jacqueline Rodriguez, vice president of research, policy and advocacy at the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education:

“We have now allowed K-12 students to be placed in harm’s way with an unprepared person at the helm of the classroom by putting them in a position where they’re not only set up for failure, but it is very unlikely that they are retained in that same position, because they were not set up with the skills, knowledge, and dispositions to be successful.”

It is a tradition of long-standing to force student teachers to pay thousands of dollars and/or go further into debt while providing free labor to schools. This, however, strikes me as a tradition rather ill-suited to our current circumstances.

If districts could pay student teachers, it just might get more people to teach. Student teachers were going to be in schools whether this bill passed or not, but color me all in favor of not exploiting them.

In the end, such proposals work at the margins. The entire teaching profession must be reimagined to attract the talent necessary to allow teachers to teach and to provide the structure necessary for students to thrive.

Some states are moving forward with this, but for the rest, the beatings will continue until morale improves.

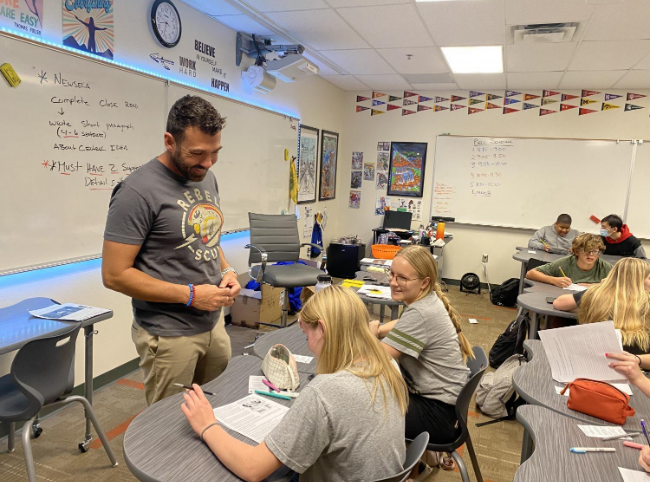

Shaun Reedy, a member of a teaching team at Westwood High School in Mesa, Arizona, says the Next Education Workforce program allows him to collaborate with other teachers, learning from their teaching styles. The model, born at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University, aims to better prepare teachers for the classroom and boost teacher retention.

Editor’s note: Today, reimaginED brings you the first in a three-part series on how the nation’s most innovative teaching colleges are preparing education majors to enter, and more important, stay in the field. We begin with the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University, ranked as the nation’s 12th overall best teachers’ college in U.S. News & World Report’s 2023 survey. The university has 4,833 students, the largest among all universities ranked, and reported $73.5 million in funded education research.

Teachers are expected to assume many roles. In a single day, a teacher must be an expert on content as well as pedagogy – also known as the practice of teaching – a social worker, a bus loop monitor, a role model, a data analyst, a trauma interventionist, and the sole classroom manager for 30 students.

In other words, all things to all students, all the time.

It’s no wonder teachers are retiring early or transitioning to other professions. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 35% fewer college students chose to major in education between 2011 and 2016. A Center for American Progress analysis of data collected by the Department discerned a 28% decline in students completing teacher preparation programs from 2010 through 2018.

Carole Brasile, dean of the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University and co-author of an article about the mounting teacher crisis published in the newsletter of the American Association of School Administrators, has a specific concern.

“More disturbingly,” Brasile wrote, “for some time we have seen that most new teachers leave the profession within three years.”

At the same time, schools continue to produce the same, often disappointing outcomes.

The Next Education Workforce initiative, developed by Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, addresses the challenge of teacher retention by transforming a one-teacher, one-classroom environment into a collaborative and more creative team-based model at locations such as Stevenson Elementary School in Mesa, Arizona.

Leaders of teacher preparation programs at Arizona State believe those two situations are linked. Recruiting more teachers and training them better will not solve the problem, they say. Only a redesign of the profession, the workplace, and how education majors are prepared for both will improve outcomes for students and teachers.

That’s the purpose behind Next Education Workforce, an ASU initiative launched five years ago that aims to craft a better future for educators, many of whom are graduates of ASU, and more personalized learning for students. The models are now in place at 27 of the state’s schools.

“Education, in general, is broken,” said Randy Mahlwein, assistant superintendent for secondary education at Mesa Public Schools and the district’s liaison to Next Generation Workforce, which involves 19 of the district’s schools, many of which are Title 1 eligible based on high numbers of low-income students. “The archaic way we designed education and implemented it over the last hundred years was designed and created for a different workforce than exists today.”

Mahlwein added that putting unrealistic expectations on a teacher and then measuring progress by annual high-stakes testing, where scores are driven by economics, is inherently unfair.

“If they had put a time frame on Thomas Edison to invent the light bulb, and then measured all his failures and discredited him to a point where he would have been washed out of the industry, he would have never invented the light bulb,” he said.

Arizona State’s Next Education Workforce program has replaced the traditional “one-teacher-one-classroom” model in Mesa schools with a teams-based model. While team teaching isn’t new, Mahlwein said, the ASU program’s models are different.

“Those (earlier) teams were working in isolation from students,” he said. “This is more wrapping teams that distribute expertise around teams of students without the limitation of time.”

At Westwood High School, for example, about 900 ninth graders are distributed across six teams. Each team shares about 150 students and is comprised of at least three certified teachers and a lead teacher, who both instructs and manages the classroom.

Other educators join the core depending on students’ needs. Their roles include special educators, teachers of English language learners, teacher candidates who are completing residencies, and paraeducators.

The models, which vary from school to school, entail “collaborative and interdisciplinary work during instructional time, as well as before and after it,” according to Basile and Brent Maddin, the program’s executive director. Planning periods are also collaborative, with daily common planning time that allows teachers to create cross-curricular lessons, discuss student work and design personalized experiences for each learner.

Instruction incorporates project- and inquiry-based learning to allow students to learn more deeply. Teachers are joined by community partners who also serve as team members. Gone is the traditional bell schedule.

Sometimes, large groups of students meet with all four core teachers for instruction, and other times they break out into small project-based groups based on student interest and teacher expertise.

In a project on the United Nations, for example, teachers work with students as they survey the globe brainstorming for ways to improve challenges.

Those challenges could touch on food or clean water, Mahlwein said. The teachers weave the standards of science, history and English into the lessons and present a bell-free three hours of instruction.

“Kids can be seen moving through the doors from classroom to classroom,” he said. “The learning is very much student-based, and everyone’s working at their own pace, with a little bit of voice and choice.”

Yet it’s no free-for-all, Mahlwein said. Teachers work within boundaries, and their students do, too.

Mary Lou Futon Teachers College, headquartered on Arizona State University’s Tempe campus, offers programs on all four of ASU’s campuses, online and in school districts throughout the state. Named for ASU education alumna and businesswoman Mary Lou Fulton, the college has two divisions: teacher preparation and educational leadership and innovation.

While teachers at participating Mesa schools are at various stages of introducing the Next Generation Workforce program, they all are honing their skills in specific areas as determined by leaders at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. Those areas, as studied in order, are:

So, how is this transformational way of training teachers working?

Arizona State leaders say early results from the pilots are showing fewer student referrals, suspensions and failed classes in secondary schools and better reading and math scores and attendance rates at elementary schools. Parents are asking for the new models to be schoolwide, and teachers are asking to be assigned to teams.

Meanwhile, the university is working with its school partners to develop a research agenda to generate evidence-based knowledge about the relationships between the models and outcomes for teachers and students. Leaders have contracted with Johns Hopkins University to serve as an external evaluator and research early implementation and impact of Next Education Workforce models.

“Ultimately, we need to prove we’re right about this,” said Maddin, the program’s executive director. “Are the models we’re building better for learners and teachers? If so, in what ways? How can we make them work better? We think that is a research agenda worth investing in.”

But Mahlwein of Mesa Public Schools already sees evidence of positive outcomes in the smiles on students’ and teachers’ faces and in workforce surveys. A team of teachers at a school in Tempe recently gave the program high marks in a promotional video.

"A job that once felt really isolating to me just does not have that feeling any more," said Mary Brown, a teacher at SPARK School at Kyrene de las Manitas. "When the day is trying, difficult, you have five other people to lean into and bounce ideas off of, and we’re always talking about students; we're always talking about achievement, and we’re always giving each other ideas and feedback on how we can do better."

Zoe Glover, a teacher candidate at Arizona State University who is on Brown's team, said the program benefits teachers and students.

"It's very enjoyable to come to work every day," she said. "And it's such a positive experience to be in the classroom. Not every student is going to connect with every single teacher, but when there're six teachers, there's no students getting lost in the cracks."

Mahlwein said their comments echo what he has observed at the participating schools in district.

“What we’re seeing at the schools that have done this at a pretty good clip are some statistically significant positive results coming from teachers working on teams,” he said. “They are across the board reporting more job satisfaction and more happiness in the workplace.”

Mahlwein added: “For so long in education, we’ve been stuck in a system of trying to do things better. It hasn’t worked for 20 to 50 years. Why would it work now? So, we’ve got to do better things.”