Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt endorsed a bill sponsored by Sen. Greg Treat to establish an empowerment scholarship program that would make every family in the state eligible for an education savings account based on its share of public school spending.

School choice opponents like the National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers often argue that vouchers, education savings accounts, and other parent-centered reforms would “drain resources” from public schools. This reasoning forces lawmakers to choose between siding with public schools (and the powerful interest groups they serve) or parents and students who want better options.

In 2022, this canard should finally be put to bed.

Data from the Department of Education shows that states have $154 billion in unspent Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds provided by Congress during the pandemic. Nationally, states had spent only $30 billion of the $184 billion in ESSER funds awarded since March 2020, approximately 17 percent, as of the end of December. This doesn’t include the $350 billion in federal funds that state and local governments will receive through the 2021 American Rescue Plan that can also be used for K-12 education.

In other words, state governments and public school districts are currently sitting on more K-12 education funding than they know what to do with.

The argument that school choice programs drain resources from public schools has always been suspect. The latest national data shows that average per-pupil spending in public schools was more than $14,000 in 2018. By contrast, education choice programs typically award children just a fraction of per-child public school spending.

This means that the government actually spends less per child when children use choice programs to transfer out of public schools. A recent fiscal analysis by EdChoice’s Martin Lueken found that school choice programs save taxpayers between $3,300 and $7,500 per participating child.

But in 2022, state lawmakers no longer need to rely on economists to determine whether public schools will have enough resources if a new school choice plan becomes law. They simply can check their state’s emergency relief funding on the Department of Education’s online dashboard tracking emergency education fund expenditures.

Consider Georgia, where lawmakers have been debating bipartisan legislation to give parents $6,000 in a “promise scholarship account” for school tuition or other instructional costs if their children transfer out of public schools. The state education agency has $5 billion in unspent federal ESSER relief funds.

In Oklahoma, Governor Kevin Stitt recently endorsed a bill sponsored by Sen. Greg Treat to establish an empowerment scholarship program. Under the plan, every Oklahoma family would be eligible for an education savings account based on its share of public school spending. The Oklahoma Department of Education currently has more than $1.7 billion in unspent ESSER funds.

In Virginia, where lawmakers are considering eight different school choice bills, the Virginia Department of Education has spent only 10% of its ESSER funds and nearly $3 billion remains available.

It’s become a cliche to say that the pandemic has changed everything. But it certainly applies to K-12 education. After two years of disrupted schooling, widespread learning losses, and a mental health crisis among a generation of children, parents and the public in many communities have a new perspective about public schooling. More people now recognize that school districts often do not act in children’s best interests.

State lawmakers across the country are actively considering legislation to fund students rather than school systems. Teacher unions and other opponents of school choice reforms have lost one of their oldest arguments against giving parents control of their child’s education funding.

With more than $150 billion in emergency K-12 education funds still unspent, it no longer makes sense to question whether we can afford to give parents the power to decide where and how their children learn. In 2022, the real question is whether we can afford not to.

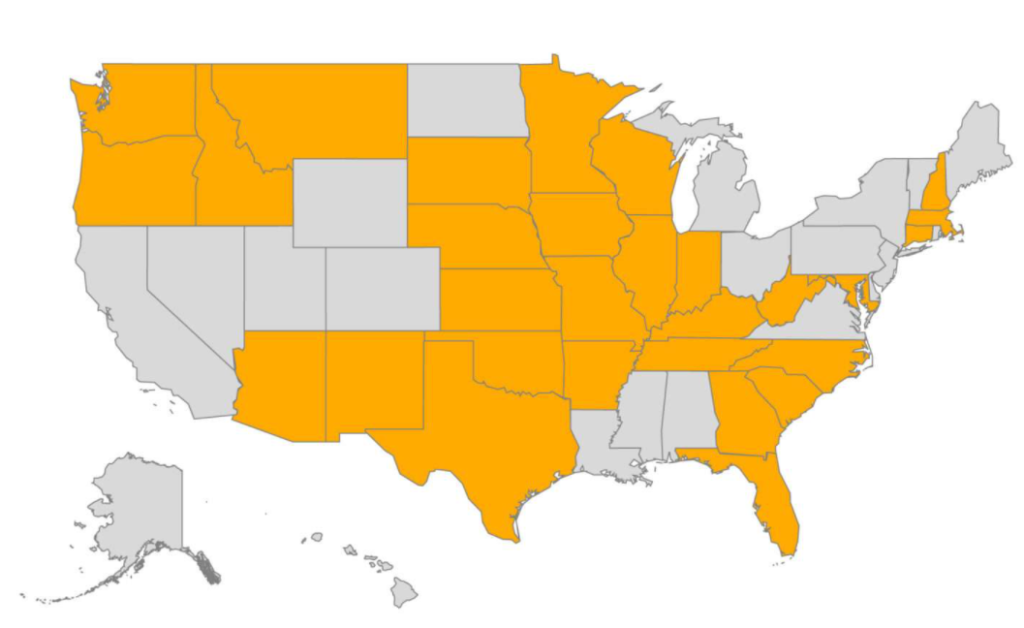

As of March 23, legislators in 29 states have introduced bills to create or expand educational choice this year.

Editor’s note: This commentary by Jayme Metzgar, a homeschool parent who is founder and president of Romania Reborn, appeared Thursday on The Federalist, where she is a senior contributor.

In February 2018, public school teachers brought West Virginia to its knees. Seeking pay raises and better health plans, unions had declared a “work stoppage” in all 55 counties, shuttering every public school in the state.

The “stoppage” — which was in fact an unlawful strike — dragged on for nine school days, costing children nearly two weeks of instruction. Under pressure, the Republican legislature rushed through a pay raise to pacify the unions.

The victorious teachers of West Virginia quickly became the darlings of the socialist left. Jacobin magazine, which had extensively covered the strike, ran a victory-lap interview entitled “What the Teachers Won.” News coverage touched off copycat strikes, beginning in Arizona and spreading to other states. The “Red for Ed” movement was born, uniting unions, socialists, and other far-left radicals in dreams of an American labor renaissance.

Flush with victory, West Virginia teachers’ unions got bolder. The next year, they went on strike again, taking aim at broader education policy. The Republican Senate had passed a bill granting teachers their second pay raise in two years, but they tied it to something for parents: school choice.

It wasn’t much—open enrollment, education savings accounts for special-needs students, and permission for three charter schools statewide. But West Virginia was one of the last remaining states without school choice, and “Red for Ed” wasn’t letting that go without a fight.

The 2019 strike lasted only two days. The West Virginia House of Delegates quickly caved, scuttling school choice and passing a “clean” pay raise for teachers.

But 18 Republicans in the state Senate stood firm. No school choice, no second pay raise, they said. Their stand forced the governor’s hand. A special session in June resulted in the passage of modest school choice measures. Open enrollment survived; so did the three charter schools. ESAs did not.

For Republicans, it seemed a small win in exchange for two costly, bruising strikes. Unions were confident that the vast majority of West Virginians were on their side.

“Educators across the state are livid at these developments and dead-set against school privatization,” wrote the Trotskyist World Socialist Web Site. “In this, they are joined by virtually all of the state’s workers and youth … 88% of West Virginians support their public schools and oppose charters.”

Leftists vowed a reckoning in the 2020 election for those 18 villainous Senate Republicans.

That was then; this is now. Last week, with very little noise or fanfare, the West Virginia legislature passed the most expansive education savings account program in America. While ESAs in most states are only open to a small percentage of children, the new West Virginia Hope Scholarship will be available to 90% of schoolchildren in the state. Every child currently enrolled in public school is eligible, plus those newly aging in.

“It’s a game-changer,” says Garrett Ballengee of the Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy, a conservative think tank and proponent of the bill. “If you add up every single ESA utilizer in the rest of the country, there are only about 20,000 of them. The Hope Scholarship will automatically open it up to ten times that many children in West Virginia alone.”

Applicants for the Hope Scholarship will receive 100% of their state education dollars — $4,600 annually — in lieu of public schooling. (County and federal funds will remain in the system.) The scholarship is usable for private school tuition, homeschool curriculum, or other education expenses. Gov. Jim Justice, a vocal opponent of ESAs as recently as 2019, has signaled he’s likely to sign.

For a state that couldn’t pass a far more modest measure just two years ago, it’s a breathtaking turnaround. What changed?

State Sen. Patricia Rucker, the Republican chair of the Senate Education Committee and chief architect of the ESA effort, has a few theories about what made the difference. First, she believes the majority of West Virginians never opposed school choice in the first place; they were simply afraid to say so.

“During the strikes, I saved a folder of all the people who wrote to me in support of the education reform. I kept all of their emails,” Rucker told me in an interview. “The vast majority of them said something like, ‘Please don’t use my name. Don’t tell anyone I wrote to you.’ They were so scared and intimidated by the teachers’ unions.”

In 2019, I wrote about the climate of union intimidation that was silencing the state’s parents and teachers. When Justice commissioned a “listening tour” to gauge public opinion, the West Virginia Department of Education co-opted the effort and manipulated its findings. This led to the much-repeated assertion that 88% of West Virginians opposed charter schools. But when the 2020 elections came around, voters finally spoke for themselves.

“I knocked on thousands of doors during my 2020 reelection campaign,” Rucker said. “Out of all those people, I only spoke to about five educators who were opposed to our education reform — that’s it. Most of the people who spoke to me about education were in favor of choice. Even the vast majority of educators I spoke to said, ‘I didn’t have any problems with charter schools. I think it would be good for us to have that opportunity.’”

The proof was in the poll returns. Despite fierce opposition from unions and their moneyed interests, all but two of those 18 education reformers returned to the Senate in 2020, and several more were added to their number. It was an affirmation that educational choice can be a winning political issue, even in states with a strong union presence. Contrary to their tightly controlled narrative, teachers’ unions hadn’t been speaking for the people. They had been shouting the people down.

The COVID-19 lockdowns undoubtedly played a major role in further widening the rift between teachers’ unions and the people. As parents suddenly faced a public school system that refused to open its doors, it became harder to understand why that system should retain exclusive control over tax dollars meant to educate children.

Public opinion polls confirm a major surge last year in support for measures to fund students directly. Remarkably, although these bills are almost exclusively advanced by Republican lawmakers, public support for school choice appears to be evenly distributed across the political spectrum. Last week, one Democrat lawmaker in Kentucky reluctantly crossed the aisle to vote against union interests on school choice, citing overwhelming support from his constituents.

“In light of COVID, people are beginning to see that different children thrive in different environments,” Ballengee said. “Some kids have done really well in virtual schooling, some have done really well in hybrid, and for some these have been an absolute disaster. It’s brought home what we’ve been saying for so long: Kids need different environments.”

Rucker believes the unions’ unyielding stance against school reopening has eroded their support among teachers as well as parents. “The media has really overplayed the unions’ voice about school reopening, as opposed to average teachers’ voices,” she said. “The vast majority of teachers I’ve heard from wanted to go back to school. They recognized that they weren’t reaching their kids through these virtual options. I would venture to say that there is a lot less union membership among West Virginia teachers these days. You can sense it.”

One indicator of this lack of union energy: after the riotous education showdowns of 2018 and 2019, the Hope Scholarship bill sailed through the West Virginia legislature with hardly a whimper of protest.

“This year when we pushed real reform, much more substantial than two years ago. It’s been very quiet,” Rucker said. “The unions don’t like the bill, but our phones aren’t ringing. We aren’t getting emails. It’s nothing like last time.”

The West Virginia United Caucus, a far-left teachers’ coalition, was active throughout the strikes and well into 2020, pushing hard against school reopening and advancing a left-leaning slate of educators to head the state’s largest teachers’ union. They haven’t published a tweet since Election Day.

“West Virginia now has the broadest-based ESA in the entire United States,” Rucker says. “It’s not the most money, but it’s the most inclusive – and in most areas, it’s enough to send a child to private school. This really is a game-changer for students and families. We’re focused on funding kids now, not institutions. We’re funding each student to get the best possible education they can get.”

Rucker is gratified by West Virginia’s 180-degree turnaround: an erstwhile union stronghold suddenly leading the way toward educational freedom. Legislatures in 29 states have considered education choice bills this year. It remains to be seen whether Republican lawmakers elsewhere will be emboldened by the Mountain State’s success.

National Coalition for Public Education

National Coalition for Public EducationThe Federal Title I program provides funds to school districts in order to improve the education of economically disadvantaged students in grades K-12. Senator Lamar Alexander (R-TN) wants to amend Title I funding so that the money is “portable,” allowing the funds to follow low-income students to their new public school.

The National Coalition for Public Education strongly opposes this idea and provides three reasons in an open letter to the Senator:

1) Ensuring the Title 1 money goes to the school where the impoverished child enrolls will lead to vouchers.

Put the tinfoil away. Ensuring that schools enrolling poor kids receive extra funding does not lead to vouchers.

2) It hurts the district’s ability to take advantage of “Economies of scale” to combine resources and help students.

Title I funding was created because there are serious problems in schools with high concentrations of poverty. To take maximize of “economies of scale” (the way the coalition argues) districts would need to keep economically-disadvantaged students concentrated in high-poverty schools, sustaining the problems Title 1 hopes to address.

Title I funding was created because there are serious problems in schools with high concentrations of poverty. To take maximize of “economies of scale” (the way the coalition argues) districts would need to keep economically-disadvantaged students concentrated in high-poverty schools, sustaining the problems Title 1 hopes to address.

3) It takes away from district’s ability to direct resources to public schools with high concentrations of poverty.

According to the left-of-center New America Foundation, $6.4 billion (or 45 percent of Title I funding), is distributed through the “Basic Grant Formula.” That formula requires districts to have a mere 2 percent economically disadvantaged student population. That low threshold means that pretty much every district is eligible for Title I funding. If funding high-poverty schools was the coalition’s real priority, why send the money through the districts first? The money should go where the needs are.

It makes one wonder if public-school organizations are less concerned with whether this money helps kids than they are with who (them) decides what to do with it.