Public education in the United States is transitioning from its second to third paradigm.

Paradigm shifts in public education occur when larger societal changes force public education to change to meet these new conditions. Current technological advances and the accompanying social changes are pushing public education into a new paradigm and a third era.

To best meet society’s current and future needs, this third paradigm aspires to provide every child with an effective and efficient customized education through an effective and efficient public education market.

A paradigm: The lens through which communities do their work

In his 1962 book, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn described a paradigm as the lens through which a community’s members perceive, understand, implement, and evaluate their work. A paradigm includes a set of assumptions and associated methodologies that guide how communities construct meaning and determine what is true and false and right and wrong.

A paradigm shift occurs when inconsistencies, which Kuhn called anomalies, begin to occur, and some community members begin to question their paradigm’s veracity and effectiveness. As these anomalies accumulate, community members begin proposing new ways of understanding and implementing their work and a prolonged contest emerges between the existing paradigm and proposed new paradigms. If a majority of the community ultimately decides a new paradigm enables them to resolve the anomalies and better understand their discipline, this new paradigm is adopted. In scientific communities, Kuhn calls these paradigm shifts scientific revolutions.

Paradigm shifts are disruptive and revolutionary because they require community members to reinterpret all their previous work and adopt new ways of conducting and evaluating their future work. Senior community members are particularly resistant to changing paradigms because their status comes from applying the existing paradigm over many years. Consequently, paradigm changes are rare and require several decades to complete.

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GTR) was a new physics paradigm that challenged Newtonian mechanics and Newton’s law of universal gravitation (i.e., the dominant physics paradigm at the time). It took over 40 years before GTR gained wide acceptance among physicists. Einstein never won a Nobel Prize for GTR because the Swedish physicists on the Nobel committee refused to accept his new paradigm.

Although Kuhn’s work focused on the role of paradigms in scientific communities, his description of how paradigms function and change is relevant for all communities, including public education. The struggle in U.S. colonial times to transition from a monarchy to a democracy was a paradigm shift. It was a revolutionary change in how government works, was fiercely resisted by those in power, and took decades to complete.

Public education’s first paradigm

Public education’s first paradigm began before the United States was a country, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the “Old Deluder Satan Act” to ensure the colony’s young people learned scripture. As the name of that early legislation implies, this first era prioritized basic literacy and religious instruction. Most children were homeschooled, and formal instruction tended to be ad hoc, improvised, and organized around the agricultural calendar.

Religious organizations provided most of the structured instruction outside the home in the 1700s and early 1800s. Children and adults attended Sunday schools, and communities organized what today we would call homeschool co-ops, which allowed rural children to receive instruction when their chores permitted.

The federal government supported public education through the U.S. Postal Service by subsidizing the distribution of magazines, pamphlets, books, almanacs, and newspapers, and establishing post offices in rural communities. By 1822, the U.S. had more newspaper readers than any other country.

Public education’s first paradigm started failing in the early 1800s as innovations in transportation and communications began connecting the country and promoting more industrialization and urbanization. About 90% of Americans lived on farms in 1800, 65% in 1850, and 38% in 1900.

This transition from rural to urban created childcare needs. Increased industrialization necessitated a more highly skilled workforce. And concerns about social cohesion grew as the growing country welcomed immigrants from Ireland and later from Southern and Eastern Europe. These were demands the informal, decentralized, and family-driven first public education paradigm was ill-equipped to meet.

Public education’s second paradigm

In 1852, Massachusetts passed the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law. This accelerated public education’s shift from its first to second paradigm.

The massive influx of European immigrants beginning in the 1830s was a primary reason Massachusetts decided to make school attendance mandatory. The U.S. experienced a 600% increase in immigration from 1840 to 1860 compared to the prior 20 years. Most of these immigrants were illiterate, low-income, and Catholic. Massachusetts’ mandatory school attendance law was intended to help turn these new immigrants into “good” Americans, meaning they needed to be literate, financially self-sufficient, and well-versed in Protestant theology.

Protestant hostility toward Catholic education in the U.S. continued deep into the following century and included the infamous Blaine Amendments that many states adopted in the late 1800s to forbid public funding of Catholic schools, and the 1922 constitutional amendment in Oregon that required all students to attend Protestant-controlled government schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Oregon amendment unconstitutional in its 1925 decision Pierce v. Society of Sisters, ensuring every American family had the right to choose public or private schools for their children. This ruling would later help make public education’s transition to its third paradigm possible.

By 1900, 31 states had passed mandatory school attendance laws. While these laws were not initially well enforced, they did significantly increase school attendance, which created management challenges.

As David Tyack chronicles in “The One Best System,” a history of how this first paradigm shift unfolded in America's cities, a new class of professional administrators, known as schoolmen, set out to modernize public education practice and infrastructure. One-room schoolhouses serving students were no longer adequate, so public education began adopting the mass production processes that enabled industrial manufacturers to create large numbers of products at lower costs. The most famous example was the assembly line that Henry Ford created to mass produce affordable Model Ts.

This new industrial model of public education replaced multi-age grouped students with age-specific grade levels that functioned like assembly line workstations. Just as Ford’s assembly line workers were taught the skills necessary for their workstations, public school teachers were trained to teach the skills associated with their assigned grade level, and children were moved annually from one grade level to the next en masse.

Mississippi became the last state to pass a mandatory school attendance law in 1918. By then the bulk of multi-aged one-room schools were being replaced with larger schools that reflected the best practices of 19th century industrial management. This was the paradigm through which government, educators, families, and the public were now seeing and understanding public education. This change marked U.S. public education’s second paradigm.

Ford famously told customers they could have any color of Model T they wanted provided it was black. Public education adopted this one-size-fits-all approach to increase efficiency. Car consumers began demanding more diverse options over the next several decades, and so did public education consumers. The auto industry diversified its offerings much quicker than public education because it faced competitive pressures the public education monopoly did not. But in 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required all school districts to begin adapting instruction to serve special needs students. This was the first instance of government requiring public education to provide a large group of students with customized instruction.

Public education’s third paradigm

This expansion of instructional diversity accelerated in the late 1970s and early 80s as school districts started creating magnet schools to encourage voluntary school desegregation. The school district in Alum Rock, California even experimented with a short-lived voucher program that fostered an ecosystem of small, specialized learning environments that today would be called microschools.

Most of the beneficiaries of early magnet schools were white middle-class and upper middle-class families who were attracted by the additional resources and high-quality specialized instruction. But magnet schools created for desegregation could serve only a limited number of students. In response to political pressure from influential constituents, school districts began creating magnet schools unrelated to desegregation, which expanded and normalized specialization and parental choice within school districts and accelerated the transition to public education’s third era.

Florida added significant momentum to this transition with the passage of its 1996 charter school law, the founding of the Florida Virtual School in 1997, and the 2001 creation of the nation’s largest tax credit scholarship program.

Two decades later, the COVID-19 pandemic further hastened public education’s current paradigm shift. Magnet schools, virtual schools, charter schools, homeschooling, open enrollment, homeschool co-ops, and tax credit scholarship programs were already expanding nationally when COVID arrived in March 2020. The pandemic turbo charged the growth of these options and newer options such as microschools, hybrid schools, and education savings accounts (ESAs).

Just as 19th century innovations in communications, transportation and manufacturing led to public education’s first paradigm shift, the rise of digital networks, mobile computing, and artificial intelligence are transforming all aspects of our lives, including where and how we work, communicate, consume media, and educate our children. These technical and societal changes are driving a decline of trust in institutions that no longer enjoy a monopoly on public information. They are also driving increased demand for flexibility to determine when, where, and with whom teaching and learning happen. Public education has begun to adopt a paradigm more aligned to 21st century demands, which include parents gaining more power to decide how their children learn.

Government’s changing role

Government’s role in public education will be impacted by a new public education paradigm that reflects these ongoing technical and cultural changes. Under the second paradigm, government had a near-monopoly in the public education market. This quasi-monopoly undermined public education’s effectiveness and efficiency because it failed to take full advantage of the knowledge, skills and creativity of students, families and educators.

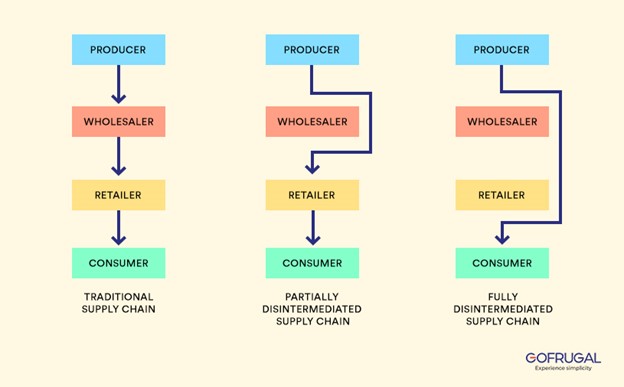

In public education’s third era, government will regulate health and safety and help facilitate support services for families and educators but will no longer be the dominant provider of publicly-funded instruction. This regulatory and support function is like the role government currently plays in the food, housing, health care, and transportation markets. Most of the responsibility for how children are educated will shift from government to families and the instructional providers families hire with their children’s public education dollars.

Shifting government’s primary role from instructional monopoly to market regulator and supporter will require operational changes. Families will be able to choose from a plethora of instructional options and will need access to information that allows them to make informed decisions, as well as education advisers who can help them evaluate their child’s needs and develop and implement customized education plans to meet these needs. Government will need to ensure data accuracy and truth in labeling – much as it currently ensures food labels accurately describe what’s in the package.

Third paradigm issues

Providing each child with a high-quality customized education through a more effective and efficient public education market will require public education’s stakeholders to rethink all aspects of how it operates. Here are some issues we will need to address.

Public education’s third paradigm has old roots

In 1791, Thomas Paine proposed an ESA-type program for lower-income children in “The Rights of Man.”

“Public schools do not answer the general purpose of the poor. They are chiefly in corporation towns, from which the country towns and villages are excluded; or if admitted, the distance occasions a great loss of time. Education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot; and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this, is to enable the parents to pay the [sic] expence themselves.”

Paine’s recommended funding method was, “To allow for each of those children ten shillings a year for the expence of schooling, for six years each, which will give them six months schooling each year, and half a crown a year for paper and spelling books.”

Over 150 years after Paine’s proposal, Milton Friedman proposed a similar but more comprehensive plan in 1955. Many of the third paradigm’s core ideas existed in the 1700s prior to the industrial revolution. But they were not technically or politically feasible.

Thanks to modern technology and a growing acceptance of families’ rights to direct their children’s education, these ideas are viable today. We can now provide every student with an effective and efficient customized public education. While all students will benefit from customized instruction in a more effective and efficient public education market, lower-income students will benefit the most because they have historically been the most underserved by the current government monopoly. Underserved groups always benefit greatly when the markets they rely on for essential goods and services are more effective and efficient.

Public education’s transition to its third paradigm is happening faster in Florida than in other states. Over 500,000 students using ESAs is rapidly improving Florida’s public education market. Floridians are seeing in real time the creation of a virtuous cycle between supply and demand. More families using ESAs is encouraging educators to create more innovative learning options, which in turn is causing even more families to use ESAs, which in turn is causing even more educators to create more learning options. These rapidly expanding options increase the probability that all students, but especially lower-income students, can find and access learning environments that best meet their needs.

Public education’s first paradigm shift took about 100 years to complete (1830-1930). This second transition began around 1975 and will likely also take about 100 years to complete nationally. Like all paradigm changes, this one is proving to be a long slog. But larger societal changes will help ensure this transition’s success.

By Shaka Mitchell

After this month’s election, which has resulted in a surprising Republican trifecta, the first action GOP lawmakers should take is to pass and sign the Educational Choice for Children Act (ECCA). This bill aims to provide educational opportunities outside the public school system for millions of students over the next four years alone.

The push for educational choice has been growing across the country, primarily driven by state legislatures, which control most K-12 education legislation. However, states like California, Kentucky, Colorado, New York, and Michigan have faced challenges in advancing such legislation, largely due to Democratic majorities and significant influence from teachers' unions.

The ECCA would create a federal scholarship tax credit program that allows tax-paying individuals to direct up to ten percent of their adjusted gross income to a Scholarship Granting Organization (SGO). SGOs already grant scholarships to students in 22 states, but they are products of state-level legislation and implicate the state tax code. Therefore, these programs are non-starters in states without personal income tax. The ECCA represents a first at the federal level and just this year the bill made significant progress, having passed the House Finance Committee.

Be like water

While subject to change, if the ECCA passes with a $10 billion cap, it would likely benefit more than a million students from low- and middle-income families. Families would apply to an SGO for a scholarship, and upon receiving one, parents could use the funds for a range of educational expenses including tuition at private schools, online courses, special education services, and tutoring. Some families will likely choose to keep their student enrolled in a public school and use scholarship funds to supplement the experience with technology or tutoring – enhancements normally reserved for more wealthy families.

The federal nature of the ECCA presents a new opportunity to deliver educational options for children in states where state legislatures have been resistant to educational freedom.

California serves as a prime example. Despite substantial investment in public education (on average more than $18,000 is spent on K-12 students in the state), student outcomes remain disappointing. Only 3 in 10 students in 8th grade are proficient in reading, according to the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

Earlier this year, and at the behest of the California Teachers Association, the state legislature defeated a proposal that would have created an $8,000 voucher program. Like water flowing around a stubborn obstacle, the ECCA would give donors and parents another option in their quest for an educational best fit.

While not a cure-all, this bill would significantly improve educational outcomes for all children.

Elections matter

Finally, the ECCA allows Republicans to fulfill the responsibilities entrusted to them by voters, ensuring a prosperous future for all children, regardless of their state's political leaning.

Famously, or infamously depending on your point of view, President Jimmy Carter established the Department of Education as a way to further endear himself to the National Education Association (NEA), the country’s largest teachers union. The Department’s creation was the fulfillment of his 1976 campaign promise, and he was further rewarded in 1980 by receiving the union’s endorsement.

In a similar fashion, candidate Trump and many other Republican candidates including Tim Sheehy (MT), Bernie Moreno (OH), Dave McCormick (PA), and Gov. Jim Justice (WV), expressed their desire to support American families through education choice. President Trump was rewarded on election night in large part thanks to increased support among Black and Latino voters.

On election night, NBC News chief political analyst Chuck Todd noted that “Latino voters align more closely to the conservative party [on] school choice.” Many of these voters live in states with little hope of state-initiated school choice legislation.

The ECCA could deepen the bonds between Republicans and Latino voters and bring much-needed opportunities to students who need them most.

— Shaka Mitchell is a senior fellow at the American Federation for Children.

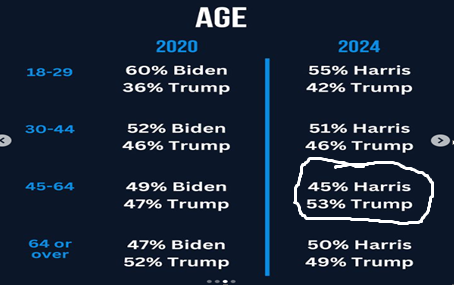

Vice President Harris received more votes from every generation of Americans except Gen X, but as it happens the loss of Gen X proved decisive. Gen X, Americans born between 1965 and 1980 (which includes your humble author) are of an age to have been the parents of school aged children during the COVID-19 fiasco/goat-rodeo.

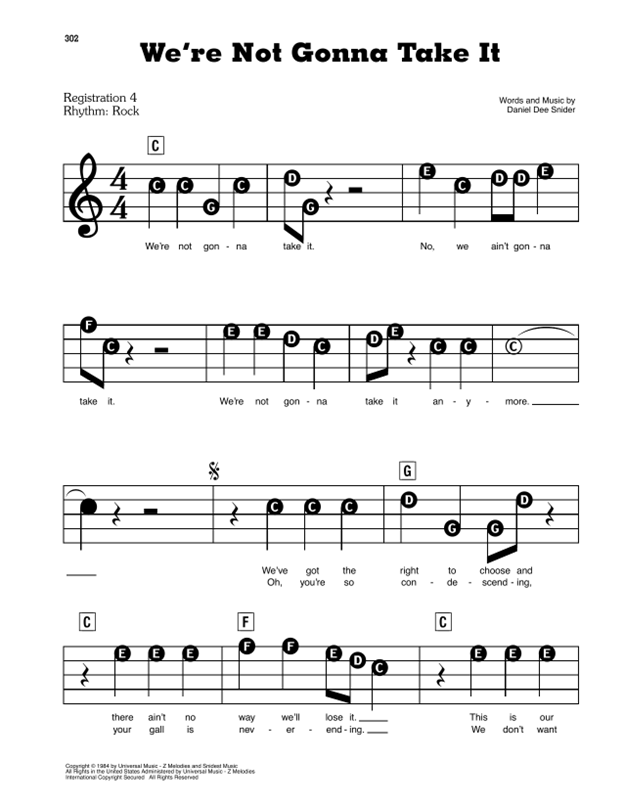

Uniquely among generations, President-elect Trump carried both men and women of Gen X. Right about now readers of a certain Gen Xish age may be humming a certain Gen X anthem. Something about having the right to choose and an unwillingness to surrender it. Feel free to belt it out in your head:

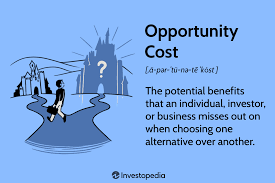

This did not exclusively play out at the national level. Over the past 10 years, for example, donors have sent an unimaginable amount of political funding into Arizona. Much of the resulting rhetoric and activity fixated upon bellyaching about school choice. As the smoke clears on the 2024 election, we find that Arizona’s 11 electoral college votes were never decisive in either the 2016, 2020 or 2024 presidential elections. Meanwhile the three “blue wall states” of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin moved in unison to determine the winner for the third election in a row. Opportunity cost is a harsh mistress.

In addition to serving as a costly sideshow in the presidential race for the third time, Arizona’s Republican Party will add to their majorities in both the Arizona House and the Arizona Senate. The battleground legislative races included a number of very tight outcomes. The parents of private choice program children outnumber the membership of the Arizona Education Association by six or more to one.

That ratio will only continue to grow. Having fallen on the losing side of the crucial 2024 legislative races, the president of the Arizona Education Association described her own organization as “union thugs.”

Hmmm…both parties might want to think about competing for the votes of families with school-age children. Those who find themselves aligned with “thugs” might want to consider losing the zeroes and getting with the heroes. If not, the beatings might just continue until morale improves. In the meantime, color this Gen Xer happy that parent power is REAL, and it is SPECTACULAR!

The big news: Yamilette Albertson Rodriguez could hardly contain her excitement. A Philadelphia billionaire whose name she had never heard before had donated $900,000 to cover tuition for her three kids and other students whose state scholarships had been ripped away by a South Carolina Supreme Court ruling.

“This is awesome!” said Rodriguez, a 37-year-old manager at a Sherwin-Williams store in the Lowcountry town of Bluffton near Hilton Head Island. “I can breathe again.”

“This is awesome!” said Rodriguez, a 37-year-old manager at a Sherwin-Williams store in the Lowcountry town of Bluffton near Hilton Head Island. “I can breathe again.”

Jeffrey Yass, a businessman and philanthropist worth $49.6 billion,. co-founded Susquehanna International Group, a Wall Street trading giant. Yass and his wife, Janine, have poured a growing share of their fortune into education causes. They most recently funded the Yass Prize, a competitive program that awarded hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants and an annual $1 million top prize to education innovators.

The Palmetto Promise Institute, which championed the South Carolina Education Scholarship Trust Fund program when state lawmakers passed it last year, broke the news Thursday morning that Yass’ donation would cover all participating students’ private school tuition through Dec. 31. The think tank is seeking donors to help cover costs until the legislature can approve changes that help the program pass constitutional muster.

"(Some of these schools) would be taking huge financial losses, especially some of the schools that took dozens of families, dozens of these ESA kids," Wendy Damron, the institute’s president and CEO told the Post and Courier. "They would take this huge financial hit and maybe be hesitant to try it again. So, he was just making an investment in our kids in South Carolina."

Catch up quick: The Education Scholarship Trust Fund was the product of two decades of efforts to pass an education choice program that was not limited to students with unique needs.

Low-income families approved for the program received $6,000 per child that parents could use for 15 different categories of expenses, including tutoring, therapy, and tuition. Months after its enactment, a group that included the South Carolina Education Association sued the state, arguing that the program violated the South Carolina Constitution’s ban on public funds being used for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution. Attorneys for the state and for the families countered that the direct benefit went to parents, not institutions, and noted the existence of similar programs for preschoolers and college students.

Low-income families approved for the program received $6,000 per child that parents could use for 15 different categories of expenses, including tutoring, therapy, and tuition. Months after its enactment, a group that included the South Carolina Education Association sued the state, arguing that the program violated the South Carolina Constitution’s ban on public funds being used for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution. Attorneys for the state and for the families countered that the direct benefit went to parents, not institutions, and noted the existence of similar programs for preschoolers and college students.

The ruling: On Sept. 11, 180 days into the school year, the state Supreme Court issued a 3-2 ruling that struck down the provision allowing the scholarships to go toward tuition, saying it didn’t matter that the parents were the ones who chose where to spend money from among a variety of schools.

The fallout: The decision left parents, whose household incomes were 200% above the federal poverty line, scrambling for alternatives if they couldn’t afford the tuition. Education choice supporters pulled out all the stops to keep the program afloat. The statewide Catholic diocese started the St. Rita Relief Fund to raise money toward the tuition of scholarship students at their schools. Palmetto Promise Institute posted video interviews of affected families. The state education superintendent asked the court to let the ruling take effect after the current school year. The governor asked the court to reconsider the ruling. The court said no to both requests. Lawmakers, who have the power to call a special session, decided not to, pledging to take up the issue in January.

Rodriguez, a Marine veteran who had served in counter-piracy operations in the Middle East, vowed to find extra work on top of her 45-hour job at the paint store to keep her teenage daughter and first-grade twin sons at the Anglican school where they were thriving.

“I started to really pinch pennies,” said Rodriguez, a single mom who also supports her 65-year-old father as he battles cancer and other health issues. To make things worse, Hurricane Helene tore shingles off her roof. She said insurance wouldn’t cover the damage, leaving her to pay for repairs herself.

After a recent food pantry visit, her daughter asked, “Mom, does this mean we’re poor?”

“It just means we’re hurting right now,” Rodriguez replied. Today’s news, she said, was just what her family needed.

“My daughter will be so happy,” she said.

For a decade, Yamilette Albertson Rodriguez served her country as a Marine sergeant. She spent seven months deployed in the Middle East where she fought to stem the tide of pirates that terrorized commercial vessels.

“My kids love that I chased pirates,” said the 37-year-old single mother of three from Bluffton, a city with a population of 27,716 in the southernmost tip of South Carolina’s Lowcountry.

Today, Rodriguez fights to make ends meet. The salary she earns as an operations manager at a Sherwin-Williams store is barely enough to support her and her 17-year-old daughter and 6-year-old twin sons. Her 65-year-old father recently had to move in with her. He’s also a military veteran and suffers from several chronic health conditions. Now he’s battling cancer.

“I’m the sole income provider,” Rodgriguez said. “I basically live at work.” Her daughter said she felt invisible in her district and sometimes struggled in math. Her twins learned to read in pre-kindergarten and were ready for first grade, but the school district required them to be in kindergarten because they turned 6 after the Sept. 1 cutoff.

“I’m the sole income provider,” Rodgriguez said. “I basically live at work.” Her daughter said she felt invisible in her district and sometimes struggled in math. Her twins learned to read in pre-kindergarten and were ready for first grade, but the school district required them to be in kindergarten because they turned 6 after the Sept. 1 cutoff.

A new state scholarship program offered lower-income families $6,000 per child that could be spent on private school tuition, tutoring and textbooks. Rodriguez wasted no time getting approved. The kids started at Cross Schools, an Anglican church-sponsored K-12 program. Her daughter was succeeding in pre-calculus and receiving support to pursue higher education. Her twins were thriving in first grade.

A month into the school year, everything changed. The South Carolina Supreme Court declared the scholarship program unconstitutional. That day, the state Department of Education notified the nearly 3,000 families whose kids were enrolled in the program that it would immediately cut off all payments for private school tuition.

“I was in shock,” recalled Rodrigeuz, who had been unaware of the teachers union-backed lawsuit that put the program in jeopardy. Her daughter offered to get a job to help her mother pay the tuition.

“She said, “I feel like with them taking this away from you, it will just burden you financially,’” Rodriguez said.

Relief could come if the state legislature calls a special session to work out a plan that passes constitutional muster. Gov. Henry McMaster this week petitioned the court to rehear the case. However, lawmakers called that a waste of time and said they will come up with a new plan when the legislature reconvenes in January. That’s too late for Rodriguez and other families, whose incomes had to be at or below 200% of the federal poverty level to qualify for the program.

Without a quarterly scholarship payment she was supposed to receive from the state in October, Rodriguez is scrambling. She is trying to develop a plan to pay out of pocket and keep her kids in their private school for at least the rest of the school year. She had been working to build her savings, but she expects the absence of the scholarship will quickly deplete those. She has even sought out food pantries for help.

“I know for a fact I’m going to be living paycheck to paycheck,” she said.

Despite all that, Rodrigeuz remains hopeful.

“My strings are tight," she said. “But I’m holding on.”

The Japanese art of pottery, kintsugi, uses gold in the process of reconstituting something broken. Rather than attempting to conceal the repair, kintsugi makes something new and even more beautiful than the original. Author Jay Wolf notes a spiritual lesson:

The story of kintsugi — this style of pottery — may be the most perfect embodiment of all our trauma-shattered lives... Instead of throwing away the broken beloved pottery, we’ll fix it in a way that doesn’t pretend it hasn’t been broken but honors the breaking—and more so, the surviving — by highlighting those repaired seams with gold lacquer. Now the object is functional once again and dignified, not discarded. It’s stronger and even more valuable because of its reinforced, golden scars.

South Carolina choice supporters have suffered a trauma in a recent ruling striking down the state’s Education Scholarship Account program. In an absurd 3-2 ruling, the majority found that the ESA program violated language in the South Carolina Constitution prohibiting “direct” state funding to private schools. ESA funding goes to a parent-directed account, which has numerous educational uses other than private school tuition. The Arizona courts, for example, recognized this distinction between ESAs and vouchers when choice opponents made a similar challenge in the Grand Canyon State. From the unanimous Appeals Court decision (which the Arizona Supreme Court later refused to reconsider):

The ESA does not result in an appropriation of public money to encourage the preference of one religion over another, or religion per se over no religion. Any aid to religious schools would be a result of the genuine and independent private choices of the parents. The parents are given numerous ways in which they can educate their children suited to the needs of each child with no preference given to religious or nonreligious schools or programs. Parents are required only to educate their children in the areas of reading, grammar, mathematics, social studies, and science.

Where ESA funds are spent depends solely upon how parents choose to educate their children. Eligible school children may choose to remain in public school, attend a religious school, or a nonreligious private school. They may also use the funds for educational therapies, tutoring services, online learning programs and other curricula, or even at a postsecondary institution.

The specified object of the ESA is the beneficiary families, not private or sectarian schools. Parents can use the funds deposited in the empowerment account to customize an education that meets their children’s unique educational needs.

Thus, beneficiaries have discretion as to how to spend the ESA funds without having to spend any of the aid at private or sectarian schools.

South Carolina students deserved a Supreme Court majority which would have recognized the soundness of this thinking. As an alternative, South Carolina choice supporters should emulate the actions of their Grand Canyon State peers in performing school choice kintsugi. It was the loss of two small voucher programs, one for students with disabilities, the other for foster care students, that inspired the creation of the nation’s first account-based choice program. Lawmakers from across the country obviously appreciated the beauty of Arizona’s kintsugi choice program, as it has been widely emulated.

While the loss in the South Carolina Supreme Court leaves thousands of families in limbo, Palmetto State lawmakers should seize the kintsugi opportunity. Judges would have to engage in truly absurd mental gymnastics to find a version of Oklahoma’s Parental Choice Tax Credit to be “direct” aid. What Oklahoma lawmakers created lawmakers in South Carolina can optimize and perfect. A perfected Oklahoma style credit could be even more robust and indeed more beautiful than the ESA program. Beauty, as Dante observed, awakens the soul to act.

The story: The nation’s education choice movement suffered its second legal defeat in as many days after the Nebraska Supreme Court on Friday put the fate of a new school choice program in the hands of voters on Nov. 5.

The story: The nation’s education choice movement suffered its second legal defeat in as many days after the Nebraska Supreme Court on Friday put the fate of a new school choice program in the hands of voters on Nov. 5.

What it means for families: The ruling and the legal tactics on both sides that led to it, throw the fate of 2,500 low-income families participating in a scholarship program that lawmakers approved to start in 2023 into uncertainty until after the November election.

Zoom in: In its ruling, the court rejected supporters’ arguments that the bill, LB 1402, which lawmakers passed as a strategic move to replace a previously approved program and keep it off the ballot, was a state appropriation and therefore exempt from a referendum. The bill was concurrently approved with LB1402A, a separate but related appropriations bill that set aside $10 million to pay for the program. However, education choice opponents purposely omitted the appropriations bill when crafting the language for the referendum. Without LB1402A, the court said, the bill was not an appropriation nor exempt from referendum.

"L.B. 1402 makes no appropriation at all, the Secretary of State has no duty to withhold the referendum based on an alleged violation of article III, § 3." the supreme court opinion said.

Catch up quick: Nebraska lawmakers approved the state’s first school choice program in 2023. It was funded by tax credits and available only to low-income families. Choice opponents fought back by gathering enough signatures to put it on the ballot for repeal. (Nebraska law allows this for bills that do not involve appropriation.) State Sen. Lou Ann Linehan, a longtime education choice champion, then moved to block the referendum by sponsoring a bill for a second program that would repeal and replace the tax credit program. Opponents gathered enough signatures to let voters decide whether to repeal that bill. A scholarship parent then filed a lawsuit asking the state Supreme Court to keep the second bill off the ballot, arguing that it was exempt because it was intertwined with a state appropriation on a second bill. Opponents left the spending bill off the petition. The high court said because the spending bill wasn’t included, the measure wasn’t exempt from a referendum.

What they’re saying: “This ruling puts Nebraska school choice in jeopardy, which is unfortunate: Nebraska families need more power, and the state more freedom, Neal McCluskey, director of Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, posted on X.

South Carolina students show their support for education choice to Gov. Henry McMaster on the Capitol steps during National School Choice Week.

A rough week for ed choice: The Nebraska high court ruling comes two days after the South Carolina Supreme Court tossed out the state’s fledgling education savings account program as unconstitutional. The court’s majority said an education savings account program violates the state constitutional ban on direct aid to private schools even though funds go to families who make individual choices. The decision leaves nearly 3,000 families scrambling to find options as the state’s education department halted tuition payments to private schools.

For David Warner, choosing a school for his son was a “very personal” decision, he said. The ability to select the place where he could learn near their home in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, made him and his family feel valued, a stark contrast, David said, to his experience with assigned public schools.

But [yesterday], a state supreme court ruling in a lawsuit supported by teachers unions will cancel the scholarships for some 3,000 children from low and moderate-income families. “It feels like the light has gone out,” David told me, “and we fear being left in the dark again.”

In 2023, South Carolina lawmakers enacted the Education Scholarship Trust Fund Program, which offered children from homes with incomes at 200 percent or less of the federal poverty line (approximately $60,000 for a family of four) the opportunity to use an education savings account. Participating families were awarded accounts worth $6,000 for use on education products and services such as personal tutoring, textbooks, private school tuition, and more. Some 19 states around the U.S. had similar account-style options for families.

Now the number is 18. The state chapter of the National Education Association (NEA), a teacher union, filed a lawsuit against the accounts last October. The South Carolina Supreme Court has ruled the program unconstitutional, saying the accounts are a “direct” benefit to private schools and violate the state constitution, even though the state awards the accounts to parents, not schools.

The ruling is devastating for families like the Warners because their child’s account may end immediately. “In just a few weeks of being in this program, we saw a completely different approach to education. We had more communication from teachers and staff, greater family interaction, and they valued our input in ways the public school never did,” David said.

He explains that the private school aligned with his family’s values and was transparent about what was being taught in the classroom. “The curriculum and teaching were totally transparent, allowing us to know exactly what our children were learning,” he said.

He fears having a “tough conversation” with his son about returning to the assigned school where he struggled to fit in. “He just made new friends, and now he may have to leave them, all because of this decision,” David said. “This ruling implies that low-income families are irresponsible and that the educational elite know better than parents, but that’s not true for us,” he says.

The Warners’ other son has special needs, and David adjusted his work commitments to care for this child. “Just because a family is low-income doesn’t mean they can’t make the best, most responsible choices for their children’s education,” David said.

Thousands of stories like this one should reach state lawmakers this fall as they prepare for the next legislative session. Policymakers can still help South Carolina families by considering other education choice innovations such as the new Parental Choice Tax Credit in Oklahoma. With this state tax credit, parents can receive tax credits worth up to $7,500 for private school tuition expenses and other education products and services. Every K-12 student in Oklahoma is eligible to apply.

Lawmakers nationwide continue to adopt new learning options for students, even in states with existing private school scholarship offerings such as vouchers. Lawmakers in Wyoming and Louisiana approved education savings accounts this year, and Louisiana added these accounts in addition to the state’s existing voucher program. Oklahoma families can “stack” their tax credits on top of the existing voucher options in that state. South Carolina lawmakers should consider solutions such as these as they look for ways to help families.

“We hope that, in the end, families in South Carolina will prevail so we can continue making the best decisions for our children,” David says. Unions shut the lights off for children in the state for now, but lawmakers have plenty of alternatives at their disposal to give families and students a bright future.

The big story: Nearly 3,000 low-income students and their families now find themselves scrambling for education options a month into the new school year after the South Carolina Supreme Court tossed out the state’s fledgling education savings account program as unconstitutional.

The big story: Nearly 3,000 low-income students and their families now find themselves scrambling for education options a month into the new school year after the South Carolina Supreme Court tossed out the state’s fledgling education savings account program as unconstitutional.

The state Department of Education announced on Wednesday afternoon that it has halted all tuition and fee payments being directed to private schools and courses. However, a department spokesperson said the actions relate only to payments made on or after Sept. 11 and that families would not have to return funds already spent. Also, all other allowable expenses would continue to be paid.

"The Department will work closely with parents to assess viable alternatives for their children if continued attendance at their current school is no longer an option, thanks to this lawsuit and subsequent ruling," department spokesperson Jason Raven said.

Raven added that the department will "do everything in its power to work with the Governor, General Assembly, and impacted schools to support the low-income families who are the victims of this ruling and will communicate with them regarding options that remain within the Education Scholarship Trust Fund program."

State Education Superintendent Ellen Weaver blasted the timing of the lawsuit, which the state NEA affiliate filed six months after the law’s passage and said the ruling “wreaks havoc” on families.

“Families cried tears of joy when the scholarship funds became available for their children, and today’s Supreme Court ruling brings those same families tears of devastation,” said Weaver, a school choice champion. “While I respectfully disagree with the holdings of the majority decision, I remain committed to working with the governor and the General Assembly to find a way forward to support these students and educational freedom for all South Carolina families. These students deserve better, and I will not rest until they get it.”

The ruling: The 3-2 decision, handed down Wednesday, ruled that taxpayer dollars can’t be used to pay for private school tuition. It relied on the state’s Blaine Amendment, which keeps popping up as the battle for education choice shifts from federal to state courts in the wake of landmark U.S. Supreme Court rulings. The wording varies by state, with South Carolina’s version stating that taxpayer dollars cannot directly benefit private schools. At issue was what qualified as a direct benefit.

Specifically, the court struck down broad sections of the Education Scholarship Trust Fund (ESTF) – a program created last year by lawmakers and administered by the South Carolina Department of Education, which provides roughly 5,000 academic scholarships totaling $6,000 each for eligible K-12 students.

Justice Garrison Hill wrote for the majority that the program already in place for this school year violates the state constitution’s prohibition against public dollars directly benefiting private schools and said he found the arguments in support of the program’s constitutionality were “unconvincing.”

“They read our Constitution as allowing public funds to be directly paid to private schools as tuition as long as the funds are nudged along their path by the student, who may, through an online portal, choose to use the funds that way,” Hill wrote, with former Chief Justice Donald Beatty and acting Justice James Lockemy concurring.

The other side: In a scathing dissent, newly installed chief justice John Kittredge, backed by justice John Few, wrote that “the majority opinion pays lip service to the policy-making role of the legislature.”

“Our constitution allows the legislature — and only the legislature — to make this policy decision,” he wrote.

Kittredge added that the funds flow through the state treasury to a third-party trust fund, then to a family’s account, which parents can direct to the school of their choice, which includes some private schools.

“The majority opinion finds this is a direct benefit to the private school, that is, that public funds are ‘immediately’ going from the State Treasury to the private school,” he wrote.

Kittredge also disputed that the program, which includes $30 million of the state’s $14 billion education budget, has harmed district schools, noting that the legislature has steadily increased funding each year and approved a record amount this past year.

School choice leaders across the nation criticized the decision and expressed sympathy for the participating families.

“Today, a court overturned a duly passed piece of legislation on the basis of an indefensible misreading of the words of our State Constitution,” said Wendy Damron, president of Palmetto Promise Institute, a think tank that supports education choice. “It is unconscionable that the Supreme Court would rip away these scholarships from children and families counting on the funds for their education this year.” Damron encouraged state education officials to appeal.

Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute's Center for Educational Freedom, responded in a post on X: “Sad news for South Carolinians.” He added that Cato filed a brief in the case “making clear, among other things, that by empowering diverse families to freely seek what they think is right, choice is important to defusing social conflict.”

Next steps: Gov. Henry McMaster said the state would ask the court to “expeditiously reconsider” its ruling due to concerns about effects it may have on other programs.

Fallout for pre-Kand college programs: The ruling comes despite the existence of other state programs that have allowed pre-kindergarteners and college students to use public funds at private schools, which choice advocates say supports the constitutionality of the K-12 ESA program. The pre-K program “is clearly in violation of the state constitution based on the school choice ruling,” Shawn Peterson, president of Catholic Education Partners, noted in an X post to point out the double standard.

Possible long-term solution: Jason Bedrick, a research fellow at the Heritage Foundation suggested that the legislature act quickly and examine other funding methods such as a tax credit program in the wake of the court’s “flawed decision.”

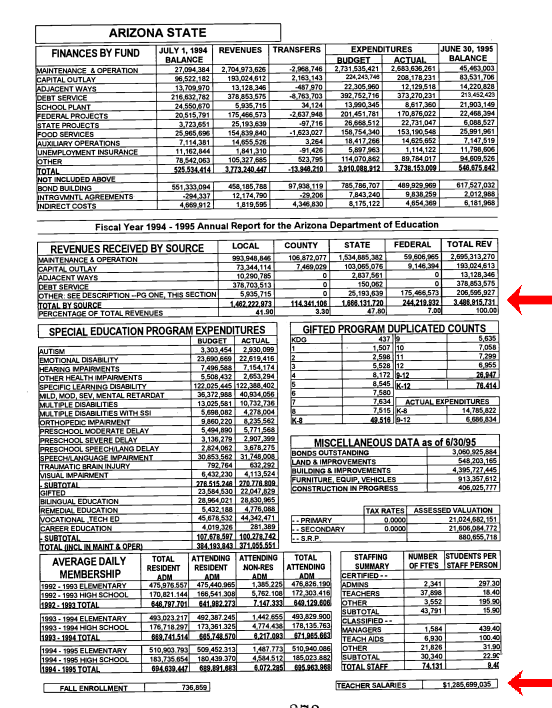

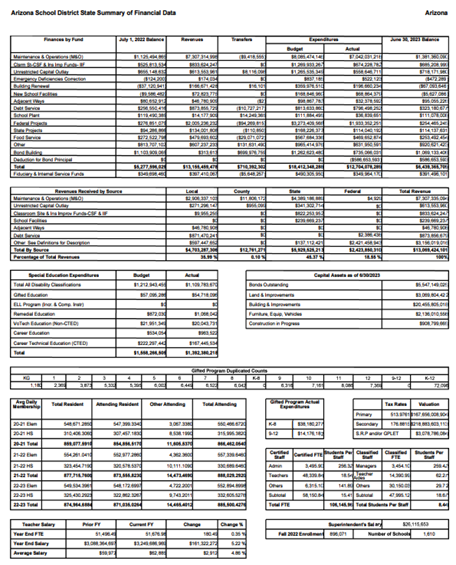

Recently, because this is the sort of thing your friendly neighborhood school choice mad scientist likes to do, I examined the Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction annual reports. Stick with me; this will be more interesting than you might suspect. So, if you go back to the 1994-95 report (the last year before any charter schools or district open enrollment) and go to page 273 you find that the Arizona school system spent almost $1.3 billion on teacher salaries, on a total spend of $3.5 billion. In other words, 37% of Arizona’s K-12 investment went to teacher salaries.

The latest edition of this same report keeps districts and charter schools separate for these calculations. In 2022-23 (see page I-253) Arizona’s total spend on school districts had increased to $13.2 billion, and the line item for district teacher salaries stood at $3.2 billion. Teacher salaries had dropped from 37% of the total spend to 25%. Dividing the total district teacher salary by the number of teachers and then adjusting for inflation revealed that the average teacher salary remained essentially flat in real terms over the 30 years.

That might seem odd at first. Arizona more than doubled the investment in school districts after accounting for inflation but somehow managed to prioritize every other type of spending except teacher salaries. How does this fit with the notion that school districts have been politically captured by teachers unions?

This puzzle is not overly difficult to solve. “Teachers unions” are actually “district employee unions,” and district employee unions can maximize their dues revenue by maximizing the employment of non-teachers. If for example you can hire two non-teachers for the same cost as hiring a single teacher, you can potentially double your dues revenue. The same reports cited above show that Arizona’s district system somehow soldiered on with one non-teacher employee per 19 students in 1994-95, but that had dropped to one per 15 students in 2022-23.

If in fact Arizona’s school districts spent 37% of their revenue on teacher salaries in 2022-23, it would have pushed the average annual teacher salary over $100,000. This could have been achieved without changing student-teacher ratios and would have left 63% of revenue to spend on everything else.

Other factors are at play as well; districts constructing buildings to the 21st century nowhere, etc. Chubb and Moe instructed us back in 1990 that the central problem in K-12 education is politics, a lesson that we seem prone to forget. The K-12 system isn’t just broken. Rather it is broken on purpose, and teachers have been hugely shortchanged in the process. Fortunately, the development of a solution is underway, and choice is key: