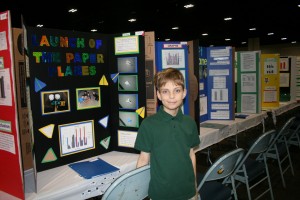

For their project, Gussie Lorenzo-Luaces and three classmates at Deer Park Elementary in Tampa, Fla., wanted to find out what kind of paper allows a paper airplane to fly the farthest. After five trial runs, they determined copy paper, with its smooth surface and stable weight, worked best.

Gussie Lorenzo-Luaces, a third-grader at Deer Park Elementary School in Tampa, was one of more than 2,000 students participating in the 33rd annual Hillsborough Regional STEM Fair last week.

The boys’ exhibit was among more than 1,800 presented at last week’s 33rd annual Hillsborough Regional STEM Fair, which featured 2,000 students from district schools, charter and private schools, and home schools.

That diversity was a big plus for Gussie’s mom, Susie, who was curious where other students in the county registered on the science track.

“I just feel they don’t need separation,’’ she said. “I like seeing them all together.’’

Increasingly, though, Hillsborough students are not all together in academic competitions.

In the past year, district officials have begun excluding charter schools from some districtwide contests, including Battle of the Books, a reading competition, and the Math Bowl and Math League for elementary and middle school students.

The reasons for the splintering are not clear. But everything from cost, to fear of competition, to a desire for charter schools to be more independent, has been suggested. At the least, the move points to potential pitfalls as school choice options mushroom across the landscape – even in a district with a choice-friendly reputation like Hillsborough.

“They’re all our children,” said Lillia Stroud of King’s Kids Academy of Health Science, a new charter in Tampa. Stroud said she can relate to the district’s concerns, but “separation at any level is disheartening.” (more…)

With 43 schools and seven more expected to open in the fall, the charter school community in Hillsborough County, Fla. has grown to the size of a small school district.

Which is why members of Charter School Leaders of Florida say having a local group to represent them is so important.

“We do feel as an organization … that now more than ever, we need to work as a group,’’ said the group’s treasurer, Mark Haggett, who also directs Academies of RCMA, elementary and middle school charters in Wimauma.

The group’s name suggests it might serve the whole state, but for now it’s limited to Hillsborough. It began informally, nearly a decade ago, as a way for charter school principals to regularly meet – like traditional public school principals – and talk about best practices, training, assessments and funding. It also was a safe place for members to vent frustrations about the district and the Florida Department of Education.

In 2007, the principals formed a nonprofit and shifted focus.

“Our main goal was to work with the superintendent and really forge a true partnership between the schools and the district,’’ said Gary Hocevar, former principal of the charter, Terrace Community Middle School, and the leadership group’s past president.

The group also organized to help lobby on behalf of charter schools for more funding – “not just for charter schools, but funding for all education,’’ Hocevar said.

The group, now headed by Cametra Edwards, principal of Village of Excellence Academy in east Tampa, represents about 35 charters. It’s among a handful of such groups in the state.

“Such organizations are definitely something we want to encourage as a state and we have already discussed some ways in which we could help that along,’’ said Mike Kooi, who oversees the office of school choice for the Florida Department of Education. (more…)

They’re one of the first things people notice when they walk inside the new Brooks DeBartolo Collegiate High School in Tampa.

Windows, everywhere.

Inside the 67,000-square-foot renovated building, light pours in through an expansive curved entryway, between the cafeteria and lush outdoor dining area, inside classrooms and even along the second-floor hallway, where students can peer down into the giant gymnasium.

Compared to the charter school’s first digs, a cramped old Circuit City it leased for five years, “this is such a change of environment,’’ said Principal Kristine Bennett.

For its new home, the school’s foundation spent $15 million outfitting a former church with 20 classrooms, two computer labs and a media center. There’s a cafeteria with a LED-powered vending machine offering gluten-free snacks, and a full-sized gym featuring one wall with a painting of a fiery red and orange Phoenix – the school’s mascot.

The striking makeover is fitting for a student body that has undergone its own metamorphosis.

Three years ago, the state gave Brooks DeBartolo a “D’’ grade for academic performance. The school, which garnered a “C’’ the year before, faced losing its charter.

One of the school’s founders and financial backers, Derrick Brooks, the legendary former linebacker for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, vowed his namesake school would work harder. And it did. The next year, it scored six points higher than the state required for an A grade.

Today, students are attending an “A’’ school for – hopefully, say administrators – the third year in a row. (more…)