An education reform era policy ended recently as New York lawmakers repealed a law that attempted to remove ineffective instructors from public school classrooms. As Kathleen Moore of the Times Union explained:

Districts can still fire probationary employees, as always. The measures that help them remove ineffective teachers who have tenure, however, have been removed. Repealed were measures that called for an expedited hearing for “just cause” termination and stated that reviews showing a pattern of ineffective teaching would be “very significant evidence” in favor of termination.

In addition, teacher evaluations will no longer have to consider test scores, student growth scores and other measures that the state tried to use from 2010 until when the pandemic hit in 2020.

If you have been hanging around the ed reform water cooler long enough, you will recall when New York City “rubber rooms” were a cause celebre back in 2009. Job security for tenured teachers reached such absurdity that NYC schools would send instructors accused of criminal activity to “rubber rooms” in order to keep students safe. Mind you these people continued to draw their salary and benefits while doing absolutely nothing. Rubber rooms existed because it was almost impossible to fire a tenured teacher.

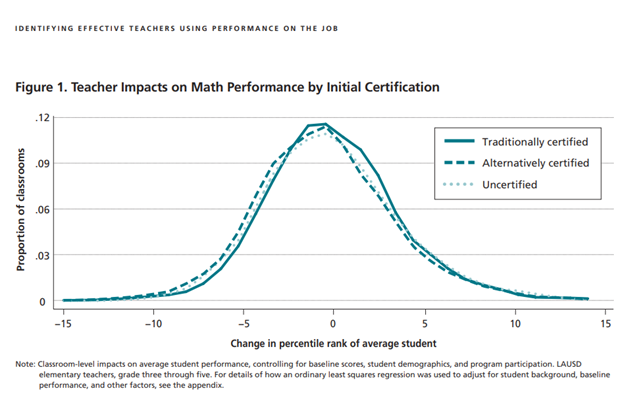

State lawmakers attempted to address this with a statewide evaluation policy that could-in theory- allow school administrators to remove tenured teachers for ineffective instruction. In theory this could have a large impact on average student achievement based upon research such as this chart from a 2006 Brookings Institution study:

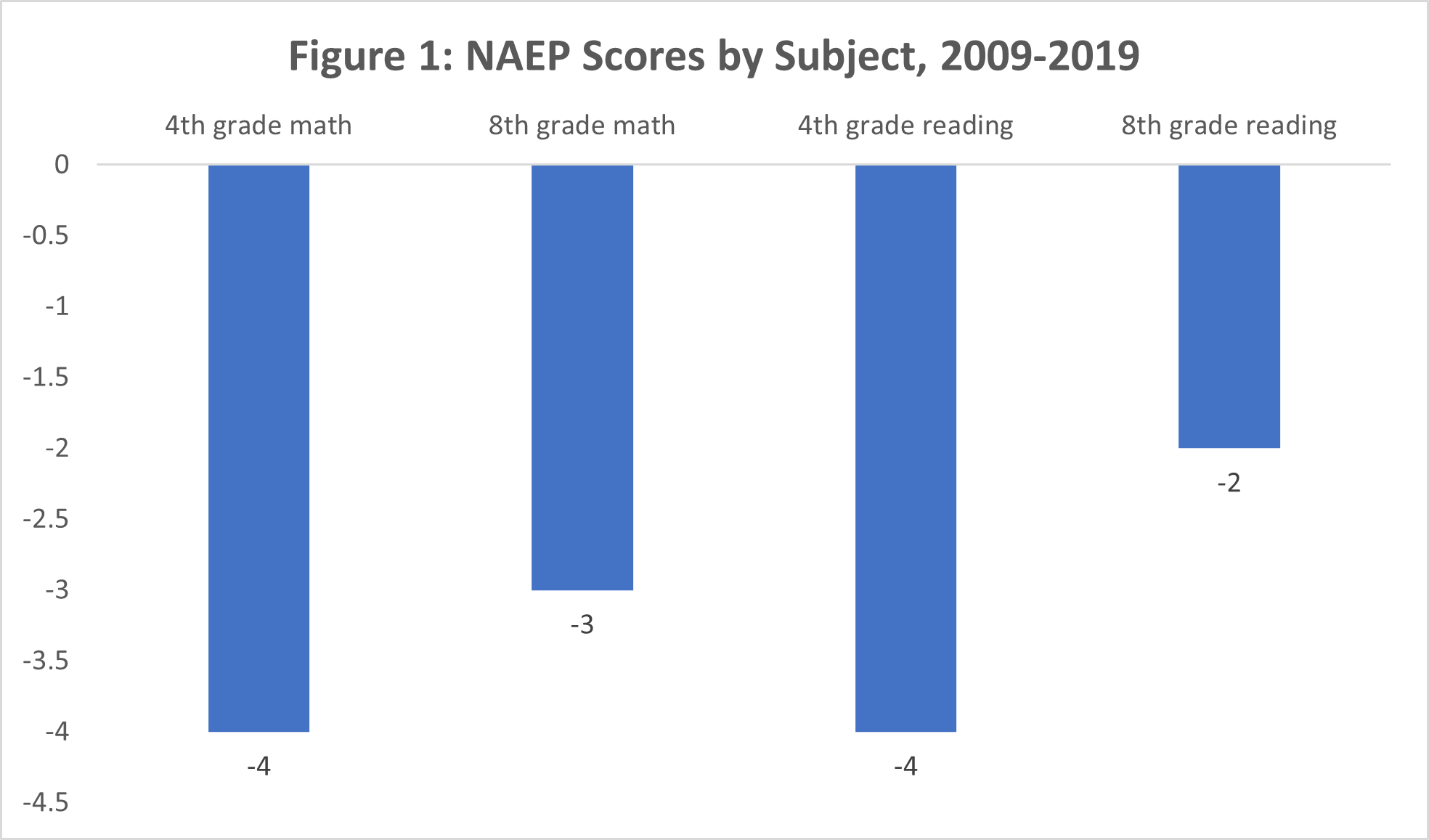

The upshot: Research shows that some teachers are catastrophically poor at getting students to learn (left side of the bell curve) while others are amazing (right side of the bell curve). Obviously what state lawmakers should do is to create a statewide evaluation system to remove the teachers on the left side, and average teacher quality will improve- in theory. As the Times Union article noted, New York had a policy to do just this in theory between 2010 and 2020. Let us then see what happened in New York NAEP scores in practice between 2009 (pre-policy) and 2019 (last NAEP under the policy and before COVID).

Of course, this does not mean that the New York teacher evaluation policy caused New York NAEP scores to decline. It does however mean that the hoped for large improvement in instruction failed to materialize. I don’t know of any data source to confirm or deny this, but I’d be willing to bet a left toe that very few teachers were removed under the policy.

Despite all the Sturm und Drang surrounding this policy at the time, it limped along ineffectually for a decade or so before repeal effectively never being implemented. It’s almost as if school districts have been subject to a deep level of regulatory capture by reactionaries with abundant ability to engage in passive resistance. Reformers bringing technocracy to a politics fight brings to mind Macbeth:

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

It also stands as a great example of Dennis Nedry attempting to get the dinosaur to fetch the stick. Education reform policies require active constituencies in order to work and last. If the supporters of top-down policies recognize this need, they have yet to display much ability to acquire them.

For years, Florida’s online schools have grappled with a logistical challenge: Getting their students to the campuses of brick-and-mortar schools, operated by school districts, to take their standardized tests.

Kevin Chavous, the president of the online learning company Stride, laid out the complications several years ago:

Imagine that a school district notifies parents that they must take their child to a location 60 miles from home for testing. Transportation will not be provided; parents are responsible for ensuring that their children arrive every day at their assigned testing site for up to a week, until all exams are complete. Families with multiple children may need to travel every day for two or three consecutive weeks, depending on the kids’ grade levels and the tests they must take. This may require making hotel arrangements and requesting leave from employers to ensure their child is present each day.

This scenario is, of course, absurd and would never happen in a regular school district. Yet it is reality for students in full-time, statewide online public schools.

One consequence of these and other mundane hurdles has been a raft of “incomplete” A-F grades whenever the state releases its annual school accountability reports.

For the 2022-23 school year, 20 of the 32 public schools that received incomplete grades were online learning institutions. The previous year, online schools accounted for 29 of 40 incompletes.

Virtual students have a harder time showing up for assessments proctored in person, or even knowing where to go or whom to ask. As a result, online schools are more likely to have fewer than 95% of their eligible students submitting test results, which can lead to an incomplete letter grade.

New legislation passed this year could help. A provision of HB 1285, a wide-ranging education bill, would set specific expectations for districts and online schools:

It is the responsibility of the approved virtual instruction program provider or virtual charter school to provide a list of students to be administered statewide assessments and progress monitoring to the school district, including the students' names, Florida Education Identifiers, grade levels, assessments and progress monitoring to be administered, and contact information. Unless an alternative testing site is mutually agreed to by the approved virtual instruction program provider or virtual charter school and the school district, or as specified in the contract under s. 1008.24, all assessments and progress monitoring must be taken at the school to which the student would be assigned according to district school board attendance policies. A school district must provide the student with access to the school's or district's testing facilities and provide the student with the date and time of the administration of each assessment and progress monitoring.

That might not fix all the logistical hassles described by Chavous, but it could help iron out some more run-of-the-mill coordination challenges with getting virtual students into physical campuses for testing.

Harvard University’s Paul Peterson and M. Danish Shakeel wrote a response to a critique of their Charter School Report Card. The authors note that I misinterpreted their study in saying that they did not control for English language learners and special education students, but they in fact did control for those factors. I will take the “L” on that and offer the authors my apologies. However, I want to explain a bit further why I believe we should approach NAEP estimates for state charter school sectors with skepticism.

NAEP is highly used and respected, and accordingly, I used to be an enthusiast for examining NAEP charter school data. However, I received a caution from a former state NAEP director that those estimates were far less than reliable. The claim went as follows: drawing a statewide representative sample of students does not ensure that you will get a representative sample of charter school students. My first reaction to this challenge was something along the lines of, “In theory, every student in the state has the same probability of being tested, and this should produce generally reliable estimates with a known amount of measurement error.” Theory is the keyword here; practice can be messy. I was told, in effect, that state charter estimates can swing wildly from test to test based on which charter schools were included and excluded from testing sample to testing sample.

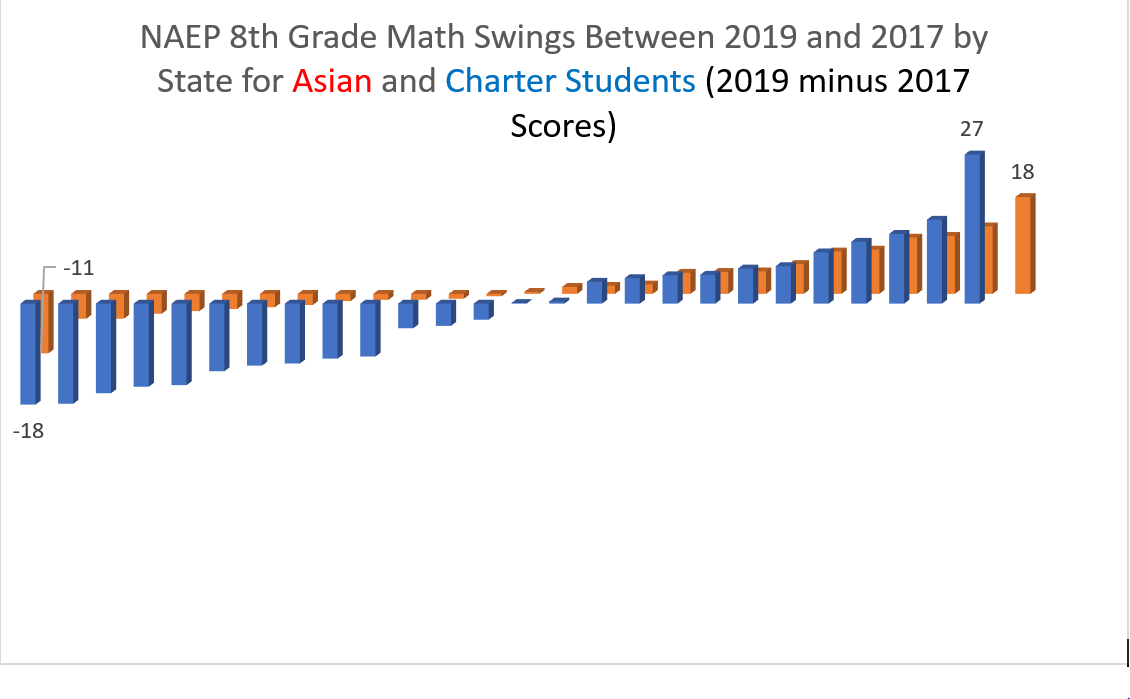

Given that my source has a lot more hands-on knowledge of NAEP sampling than me, I decided to eyeball the data. For example, the percentage of Asian students (4.9%) is smaller even than the percentage of charter school students (7.9%). In theory, Asian students should be more difficult to reliably sample than charter school students. In practice, Asian scores look much more stable than charter school students:

Does anyone else find it a bit implausible to think that South Carolina charter school students experienced a 27-point improvement between 2017 and 2019? South Carolina charter schools also notched a 29-point increase in their eighth grade reading scores between 2017 and 2019, which was four times larger than the largest increase in an Asian score in a state. Maybe South Carolina charter students were living right, or just maybe something odd is going on in the sampling. In any case all this bouncing around led me to believe that my former state NAEP director source knew of what they spoke.

Does anyone else find it a bit implausible to think that South Carolina charter school students experienced a 27-point improvement between 2017 and 2019? South Carolina charter schools also notched a 29-point increase in their eighth grade reading scores between 2017 and 2019, which was four times larger than the largest increase in an Asian score in a state. Maybe South Carolina charter students were living right, or just maybe something odd is going on in the sampling. In any case all this bouncing around led me to believe that my former state NAEP director source knew of what they spoke.

Peterson and Shakeel note, "By combining results from 24 tests over an 11-year period, the chances of obtaining reliable results are greatly enhanced.” I agree with this, but don’t find it necessarily assuring. While pooling is a good idea, as random errors can cancel out, there is no guarantee that they will do so. For example, in 2016, the “poll of polls” approach predicted a thumping Hillary Clinton electoral college victory relying upon a similar pooling approach. If you poll a group of noisy estimates, it is possible that the result will be noise.

In my original post, I offered the opinion that Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Project data would be a better source of data due to two large advantages. First, the Stanford data, by linking state testing data across the country, contains a much larger universe of schools and students over a continuous 10-year period. Second, the Stanford data includes a measure of academic growth, which is not possible with NAEP. Scholars widely regard academic growth as the best measure of school quality.

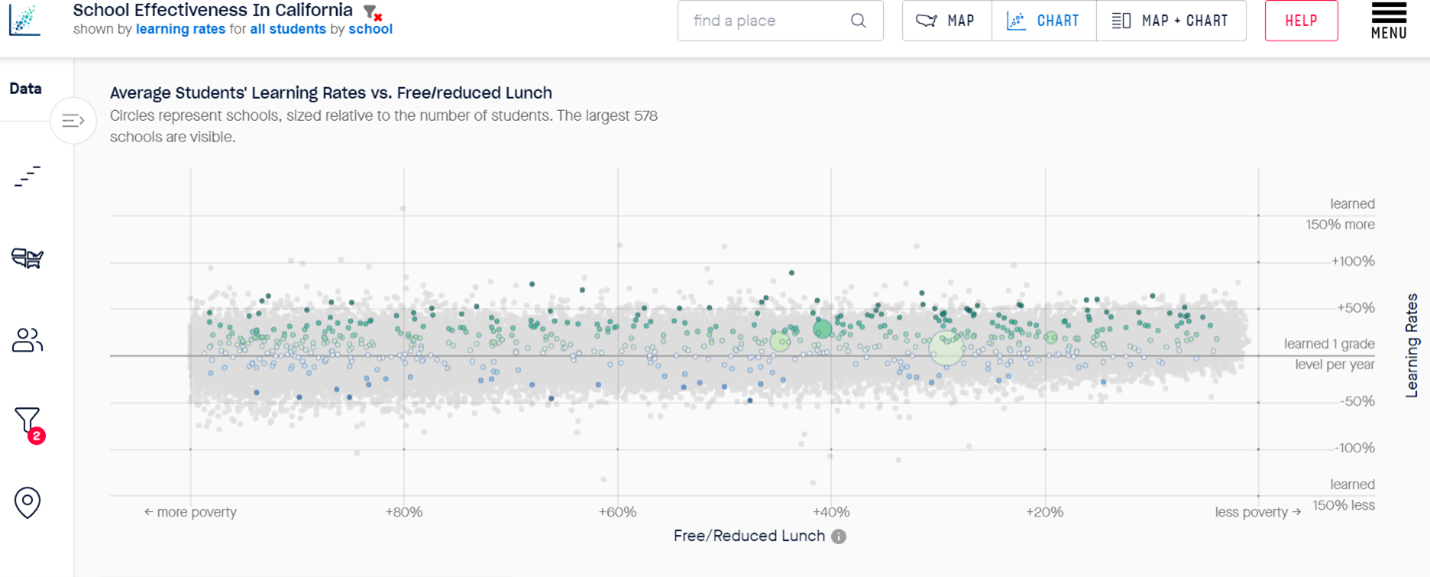

Peterson and Shakeel’s rankings put California’s charter sector in the bottom half of their ranking (25th out of 36 state sectors). If we go to the Stanford data and examine the growth data of California charter schools, it looks like this. (Green dots represent high-growth schools, and blue dots represent growth schools.)

Does California have a high-quality or low-quality charter sector? The answer might hinge on whether you want to place your trust in the modeling of noisy NAEP estimates or alternatively trust your own lying eyes. I’m inclined to go with the eyeball test.

Peterson and Shakeel, however, are not sold on the superiority of the Stanford data. “But Ladner would have us use the problematic SEDA test data because SEDA reports changes in student performance in each school district and charter school from one year to the next. That requires yet another assumption: that there is no change in the composition of a school cohort from one year to the next, a particularly strong assumption for a school of choice.”

Stanford’s data may be “problematic” but that seems like a weighty charge. My claim is not that NAEP data is generally problematic, merely that their estimates for charter students are very noisy, which was a claim brought to my attention by a knowledgeable source and which I investigated. There of course is a change in the composition of the charter sector school cohort form one year to the next and the same is true of the district school system. If this is a systemic issue, I don’t believe there is any reason to suspect that NAEP is any more immune to it than the Stanford data.

I commend Peterson and Shakeel for creating an outcome-based measure of charter school sectors. I think it is an important topic and worthy of discussion and debate as to which measurers of academic achievement and which data sources should be used.

Florida released a new batch of A-F grades to schools, but without some of the usual negative consequences.

The 2022-23 school year was the first under a new state assessment system. The state has waived any negative consequences stemming from low school grades in this initial baseline year.

Among the beneficiaries of this safe harbor are two charter schools that received their second consecutive F grades: Duval County's Wayman Academy of the Arts and Hillsborough County's Village of Excellence Academy.

In normal years, they would face automatic closure unless they could show their performance was comparable to that of nearby public schools. That and other consequences will resume in future years. The state offered a similar accountability pause in 2015, the last time it made a major change in assessments.

The state Department of Education calibrated this year's school grades to match the distribution of letter grades given out in the 2021-22 school year. Manny Diaz Jr., the state's education commissioner, described the 2022-23 letter grades released today as a "starting point for future achievement."

The transition to a new assessment system also means the state does not yet have data on the learning gains students have made from one year to the next. That means this year's letter grades primarily reflect students' test scores, as well as acceleration and graduation rates in middle and high schools. Learning gains will return in future years' school grade calculations.

A few months ago, the latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress – the gold standard of standardized tests – showed Florida, again, made a national splash. This time, it notched the biggest gains in America.

Florida now ranks No. 1, No. 1, No. 3 and No. 8 on the four core tests on The Nation's Report Card, after adjusting for demographics.

You’d think the biggest gains in America would prompt applause from school boards, superintendents, teacher unions, and allied lawmakers. But no. In Florida, good news about public schools is increasingly ignored by public school groups; media coverage is mostly crickets (recent exception here); and alternative facts seed conspiracy theories.

No wonder, then, that plenty of candidates for political office are again vying to see who can flog the system the most. One gubernatorial candidate says “we are experiencing a true state of education emergency,” citing a single, obscure (at least in education circles) ranking, based on an especially crude set of indicators. Another says “Florida’s education reform has been a failure” while citing no evidence at all.

Deny and distort. Refuse to acknowledge progress. Demonize anybody who does. This is what “debate” over Florida education has come to.

Measures like NAEP scores continue to show the system is not only better than ever, but, in some ways, among the best in America. Yet to many, it’s still Flori-duh.

The tragic result is Florida teachers don’t get credit they deserve. And every day Floridians have no idea their public schools are on the rise.

Consider:

I get The New York Times. Each morning, it identifies the world's battlegrounds — military and ideological, political and economic. I discount and forgive its plainly "liberal" bent. If I owned a paper, it would have a tone of sorts.

But there are limits. One, I suggest, is the duty of all media, at an ethical minimum, to recognize, if only to dismiss, plausible arguments on all sides of any public issue. Readers deserve to know the writer's pre-judgments.

The Times is a collection of heady folk; one expects the best from them. Sadly, along with most of their profession, they have remained silent on the strongest argument for extending to the lower-income parent the same power of choice among all educators that is available, and so precious, to our middle- and upper-income classes.

In April, the Times offered its view on the efficacy of one form of empowerment for the non-rich under the headline: "Vouchers Found to Lower Test Scores in Washington Schools." The article discussed a study originating from the anti-voucher Obama Department of Education; it found that vouchers for choice of private schools by poor families in D.C. were followed by slightly lower scores on required tests. The Times cited a few concurring studies but strangely failed to note that these reports contradict two dozen other professional analyses.

But that particular form of selective reportage is not the only concern here. Much more troubling is the Times writer's assumption that test scores are the litmus test for success in school, and that, if scores slightly declined, there would be no justification for letting poor parents make those choices so dear to the rest of us.

The test score infatuation is still widely shared by the media. Historically, it stems in considerable part from the purely economic argument for choice so welcome to the utilitarian minds of the '60s and even today. (more…)

Grassroots Free School offers traditional classes in core subjects, but attendance is not mandatory. The school allows students to direct their own learning. It also accepts tax credit scholarships for low-income students.

This is the latest post in our occasional series on the center-left roots of school choice.

The tiny Grassroots School in Tallahassee, Fla., is democratically run. Everybody votes on everything. Some of its 24 students recently led a successful bid to limit use of school computers. Others debated whether Grassroots should raise chickens or rabbits. The chicken faction won.

School choice has been on the agenda, too.

And for those who think choice is a good thing, good news: After a decade-long hiatus, the 42-year-old “free school” is again among the 1,600 private schools in Florida that accept tax credit scholarships for low-income students.*

“We want to serve all families,” not just those who can afford tuition without scholarships, said Kim Weinrich, the school’s chief academic officer. “That’s very important to us.”

Given the myths that fog perceptions about school choice, it’s noteworthy a school like Grassroots is participating in the nation’s largest private school choice program.

The “hippie school,” as it’s jokingly called, is rooted in one era but branching into a new one. In the 1960s and ‘70s, hundreds of schools like it mushroomed across America, nourished by a counterculture compost that rejected bureaucracy and uniformity. According to the Alternative Education Resource Organization, at least 100 remain.

A handful of families started Grassroots when Tallahassee was particularly fertile ground for liberal activists concerned about war, racism, pollution. “They were trying to figure out how we can improve,” in education and every other sphere of life, said longtime supporter Jan Alovus.

A self-described back-to-the-lander, Alovus migrated to Tallahassee in 1981, drawn by the city’s rep as a “cooperative community.” She paused, though, at sending her children to public schools: “I had been with them every day of their lives and all of a sudden somebody else was in charge of them?” she said. “That was odd to me.”

The remedy? Alovus and others started a land co-op that set aside four acres of oaks and magnolias for Grassroots. The school is still there, a stone’s throw from one of Tallahassee’s impossibly lush canopy roads and on the fringe of a sea change in public education. (more…)

Low-income students in Florida continue to outpace their peers in most other states, with particularly strong, relative outcomes in some of Florida’s biggest urban districts, according to national test results released this morning.

The overall results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress were not flattering for Florida or the nation. Often called “the nation’s report card,” the NAEP math and reading tests are given every other year to representative samples of fourth- and eighth-graders in all 50 states.

The 2015 results showed national averages falling in three of four tested areas and stalling in one. In Florida, they stalled in three and fell sharply in one: eighth-grade math.

But on the bright side, low-income students in Florida, which has among the highest rates of low-income students in the nation, now rank in the Top 10 in three of the four tested areas, including No. 1 in fourth-grade reading.

Next to their peers in 18 other urban districts, low-income students from the Duval, Hillsborough and Miami-Dade districts in Florida also shined. The latter were particularly impressive, finishing No. 1 in three of four categories and showing statistically significant gains in fourth-grade math and eighth-grade reading.

The latest NAEP results come as high-stakes testing and other regulatory accountability policies continue to draw fire around the country, and as many states begin phasing in academic standards spurred by Common Core. Florida fully implemented new standards in the 2014-15 school year.

The Sunshine State’s NAEP scores rose rapidly between 1998 and 2007, but have been mostly flat in three of four testing cycles since. This year, its eighth-grade math scores tumbled, with 64 percent of eighth-graders scoring at basic or above, down from 70 percent in 2013.

At the same time, the overall numbers tend to mask the performance of Florida's low-income students, who are now a solid majority of the state's K-12 enrollment. According to the most recent federal figures, 57.6 percent of Florida students are eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch, putting the state at No. 44 nationally (from least to most).

In the late 1990s, Florida's low-income students were in NAEP’s bottom tier when compared to low-income students elsewhere. But now they’re tied for No. 1 in fourth-grade reading, tied for No. 5 in fourth-grade math, and tied for No. 9 in eighth-grade reading.

After this year’s big drop, though, they’re also tied for No. 34 in eighth-grade math, falling from No. 21 two years ago. (more…)

Charter schools. The Plato Academy charter schools in Pinellas are academically knocking it out of the park. Tampa Tribune.

Tax credit scholarships. Senate President Don Gaetz, who pushed for stronger accountability and transparency in the program, says in an op-ed that as a former school board member he is "ashamed" of the Florida School Boards Association suit against tax credit scholarships. Northwest Florida Daily News. "An end-run around the will of the people," writes Walt Gardner in Edweek. Howard Fuller's call for the fight in Florida to go national gets some ink on Gradebook. Whitney Tilson says its sad to see Charlie Crist sell out Florida kids.

Tax credit scholarships. Senate President Don Gaetz, who pushed for stronger accountability and transparency in the program, says in an op-ed that as a former school board member he is "ashamed" of the Florida School Boards Association suit against tax credit scholarships. Northwest Florida Daily News. "An end-run around the will of the people," writes Walt Gardner in Edweek. Howard Fuller's call for the fight in Florida to go national gets some ink on Gradebook. Whitney Tilson says its sad to see Charlie Crist sell out Florida kids.

Common Core. Jeb Bush directs criticism to President Obama. Washington Post.

Satanists. They'll be handing out material in Orange County public schools this year. Orlando Sentinel.

Testing. Education Commissioner Pam Stewart drops a requirement for FAIR testing for students in K-2 after an Alachua County kindergarten teacher refuses to administer it. Tampa Bay Times. Miami Herald. Gainesville Sun. Florida Today. Answer Sheet. (more…)

Tax credit scholarships. The bill expanding the program is likely headed to the House floor. More from the Scripps/Tribune. Times/Herald. News Service of Florida. The state should mandate that scholarship students take the state's standardized science test too. Bridge to Tomorrow. Education activist Rita Solnet tears into the program on the Huffington Post, which is also picked up by the Answer Sheet. The legislation is controversial. Sun-Sentinel.

Charter schools. The Sarasota County school board renews a charter contract after a contentious debate. Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

Magnet schools. Two new Pinellas County programs are flooded with applications. Tampa Bay Times.

Testing. The first priority in choosing the state's next assessment was having it ready for next year, Education Commissioner Pam Stewart said Tuesday. Gradebook. Field tests from Utah can inform officials about how the new tests will work. WFSU. The new test should be an improvement from the FCAT, the Sun-Sentinel editorializes. South Florida schools tweak their testing calendars to accommodate Passover. Miami Herald.

Funding. The House's budget proposal would boost spending on public schools. Times/Herald.

Administration. Alachua County finds eight semifinalists for superintendent. Gainesville Sun. Hillsborough officials spar over transportation issues. Tampa Tribune. Tampa Bay Times.

School safety. Bill aims to make it safer for kids walking to school. Gradebook. Hillsborough Schools hire a new security chief. Tampa Bay Times.

Homework. The load isn't all that heavy for most students, a Brookings Institution report says. Orlando Sentinel.

Employee conduct. A former Manatee High School assistant principal is in a legal fight for his job. Bradenton Herald. A Brevard County high school teacher is on paid administrative leave after showing students a nude picture, in what was apparently an accident. Florida Today.

School facilities. A rural elementary school re-opens after mold problems. Florida Times-Union. More from the Independent Florida Alligator.