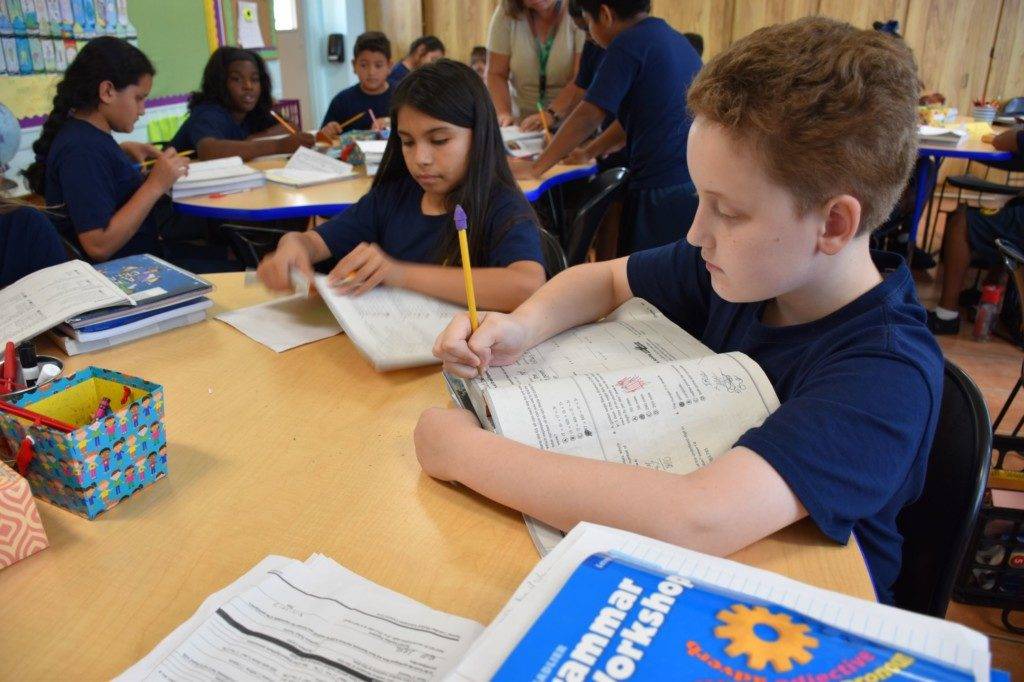

Students at Lourdes Academy have begun participating in the Program for Inclusive Education (PIE) for students with specific learning needs or diagnosed disabilities.

The losses were small but concerning. On average each year, two students with learning needs were leaving Lourdes Academy in Daytona Beach.

Like many other Catholic schools, Lourdes simply did not have a full-time staff person to help meet the needs of those students. According to principal Stephen Dole, that deficit made it hard for the school to identify the students and the interventions they may need.

“When you think of 225 students you have and out of those 25 are struggling, that is a decent number you have to allocate resources to,” he said.

When Dole learned of the Program for Inclusive Education (PIE) at the University of Notre Dame’s Alliance for Catholic Education, he thought the program was just what the school needed. PIE trains teachers to identify students with specific learning needs or diagnosed disabilities and directs them in implementing evidence-based practices that have been proven effective for struggling learners. The 13-month program allows teachers to become certified in exceptional needs and mild intervention.

Lourdes was the first of three Catholic schools in the state to complete the program, which was founded in 2016. In total, 32 schools in 16 states have participated.

Now, there are two teachers certified at Lourdes to deal with mild to moderate interventions, one of whom is dedicated full-time to meet the needs of struggling students.

“We are hopeful to be able to retain the students,” said Dole. “We want them to be on grade level before they graduate. We want to continue to meet the needs of as many students as possible.”

According to the University of Notre Dame, 87 percent of dioceses surveyed report that schools do not have the capacity to meet the needs of students with learning differences. The National Center for Education Statistics also reported in 2017 that 78.4 percent of Catholic schools serve students with mild to moderate special needs.

Overall, 5.1 percent of students in Catholic schools have a diagnosed disability, according to the National Catholic Education Association.

Amy Matzke, director of student support at Lourdes Academy, said that prior to the PIE training the school struggled through trial and error to find the best interventions for those struggling students. Matzke said now she has evidence-based protocols that guide her through her curriculum-based measures that are targeted to each student’s needs.

Matzke leads a team of paraprofessionals who can pinpoint struggling students and determine the best solution for them: intervention, another teacher in the classroom or a small group setting.

“We are able to look at an actual behavior or learning issue,” Matzke said. “We are able to decide why this happened, what we need to do to fix it and implement it right away. “

Lourdes serves 225 students, of whom 145 use the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income students. That scholarship is administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which publishes this blog.

The school was chosen as a National Blue Ribbon School in 2006 by the U.S. Department of Education. When the economy weakened in 2008, many parents pulled out their kids, said Dole.

When Dole became principal in 2016, he implemented a higher measure of accountability for students and parents. He brought on a full-time curriculum coordinator to strengthen the curriculum working directly with teachers to implement best practices. Personnel changes were also made.

The school currently includes students from all backgrounds: 50 percent are white; 25 percent Latino; 20 percent black; and 5 percent Asian or mixed race.

Since changes were implemented in the last three years, students have continued to make academic progress, scoring well above the national average of 50 percent on Iowa assessments, according to Dole.

Beyond Lourdes Academy, the mission of PIE is to equip Catholic schools with the culture, foundation and resources for educating all students inclusively while celebrating every student’s diverse and exceptional characteristics, said Christie Bonfiglio, director of PIE and director of professional standards and graduate studies at Notre Dame.

“PIE advocates for empirically-validated instruction so teachers are implementing what works,” Bonfiglio said. “In addition, we train teachers to collect valuable data and to make good decisions based on the evidence.”

Historically, Catholic schools have been slow to open their doors to students with diagnosed learning needs, Bonfiglio added, but “now we are seeing more advocacy and a bigger push to serve academically diverse students in all schools.”

Notre Dame began supporting the mission of inclusion through the Teaching Exceptional Children Program in the summer of 2010. The program was revised over the years to better meet the needs of struggling learners and students with disabilities.

“Nationally, academic diversity is prevalent in all schools,” said Bonfiglio. “That is, there are struggling learners and students with disabilities (diagnosed or not) in the classrooms in Catholic schools across the country. It is our responsibility as Catholic educators to welcome these students and ensure that their needs are met.”

Charter schools: Three Broward County charter schools could owe the state as much as $1.5 million for failing to provide sufficient instructional hours and receiving funds for ineligible students, and the district is worried it may get stuck with the bill. Sun Sentinel. More from the Miami Herald.

Faith-based schools: The University of Notre Dame and the Alliance for Catholic Education park their national tour bus at Sacred Heart in Pinellas Park to promote Catholic schools. redefinED.

Better Ed: Let's remove the hurdles, reduce the bureaucracy, and empower teachers with the resources and autonomy to allow them to do their jobs, writes former Florida Sen. Paula Dockery for The Ledger. Florida students of all races Continue to meet higher standards in education. Sunshine State News.

Better Ed: Let's remove the hurdles, reduce the bureaucracy, and empower teachers with the resources and autonomy to allow them to do their jobs, writes former Florida Sen. Paula Dockery for The Ledger. Florida students of all races Continue to meet higher standards in education. Sunshine State News.

Common Core: Florida Parents Against Common Core co-founder Laura Zorc says she is undaunted by the Florida State Board of Education’s vote pushing forward the Common Core State Standards and will continue to fight to stop implementation of the new measures. TC Palm. An Orlando mom explains why Florida's testing policy needs to change. StateImpact Florida.

School boards: Palm Beach County School Board members warn the superintendent that if he doesn't hire a chief of staff soon - they will. Palm Beach Post. Charles Brink, the businessman-turned-education advocate, is not running for the Hillsborough County School Board after all. Tampa Bay Times.

School spending: The Manatee County School District Audit Committee calls the internal information technology department "outdated and inflexible." Bradenton Herald. Rising prescription drug costs and coverage plans for retirees may add up to higher health insurance costs for Pinellas County school employees next year. The Tampa Tribune.

Teachers: Hillsborough County's top teacher of the year finalists welcome the challenges of modern education. The Tampa Tribune.

Bullying: Harlem Globetrotter Shane “Scooter” Christensen talks to Pensacola elementary students about bullying and its impact on schools. Pensacola News-Journal.

Conduct: The Broward School Board dismisses its complaint against a Weston teacher accused of sleeping at his desk after an administrative law judge says it's impossible to prove the educator dozed off. Sun Sentinel.

Bishop Robert Lynch of the Diocese of St. Petersburg helps celebrate the growth of Sacred Heart Catholic School in Florida, and other Catholic schools across the state during the University of Notre Dame's Alliance for Catholic Education bus tour that made a stop in the Tampa Bay area.

Nearly two decades ago, Sacred Heart Catholic School in Pinellas Park, Fla. was on the “death watch list,’’ said Bishop Robert Lynch of the Diocese of St. Petersburg. Families struggled to afford private school tuition, enrollment dwindled and tough decisions loomed for school leaders.

But instead of closing the school, Lynch forged a partnership with the University of Notre Dame and the Alliance for Catholic Education, a graduate program that trains future Catholic teachers and leaders.

Nearly 17 years later, Sacred Heart has more than 200 students and, like other Tampa Bay area Catholic schools, is expecting more growth in the years to come. It’s a success story that owes a lot to ACE.

“It saved these … schools,’’ Lynch told redefinED Wednesday, during a celebration that brought a giant blue RV emblazoned with the University of Notre Dame and ACE logos onto the grounds of Sacred Heart.

The stop was part of a national 50-city tour called Fighting for Our Children’s Future. It’s designed to raise awareness about the value of Catholic education and the profound impact it can have on children’s lives. It also stresses the need to keep Catholic schools relevant, active – and open. More than 1,300 U.S. Catholic schools have closed in the past 20 years.

“I just knew ACE coming to our diocese would be a blessing,’’ Lynch told an audience of students, parents, school donors and ACE leaders. “ACE is grace. It is the catalyst. It’s been the yeast that has raised the leaven – and the Catholic education.”

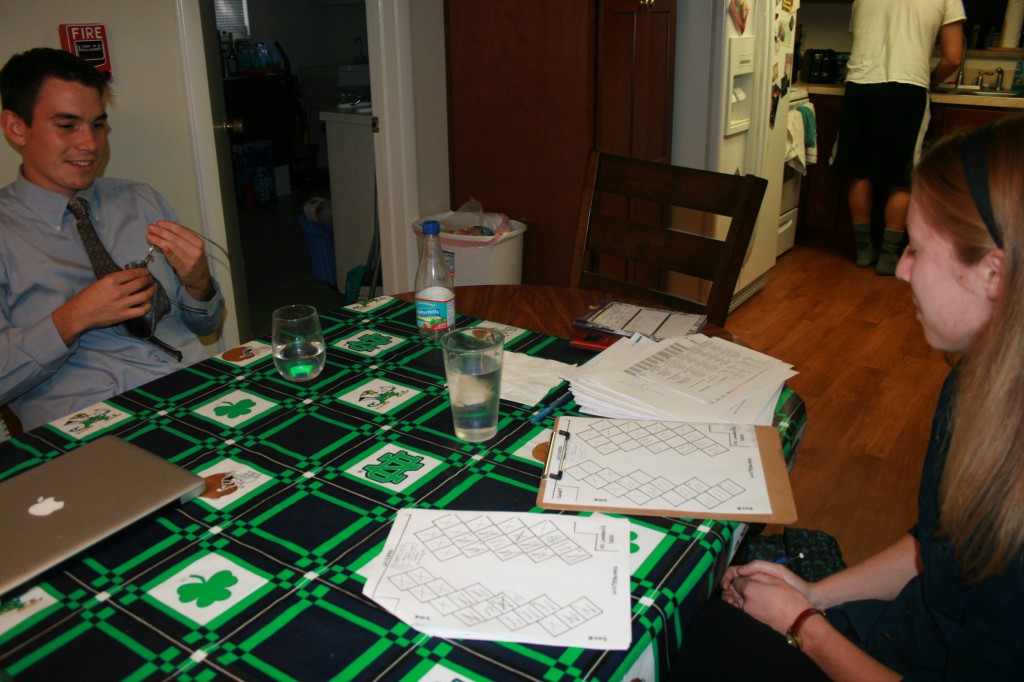

ACE teachers-in-training Ben Horton and Ashley Logsdon talk about being a part of the University of Notre Dame's effort to revive Catholic schools. Both students are earning a master's degree in education, teacher certification and the experience of a lifetime as they lead classes at local Tampa Bay area schools.

While getting a history degree at a small Catholic college in New Hampshire, Ben Horton figured he had two options after graduation: law school or teaching. Then, a scholarship his junior year sent him to Belfast, Ireland, where he taught at a Catholic school near the Peace Walls dividing Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. There, among the children of working-class families struggling with violence, drugs and teen pregnancy, he discovered a passion for teaching – and his faith.

“I like trying to give kids some hope, some opportunity, some guidance,’’ Horton said.

Now the 24-year-old University of Notre Dame graduate student teaches middle-schoolers at the Holy Family Catholic School in St. Petersburg, Fla. It’s part of a two-year service program developed by the Indiana university’s Alliance for Catholic Education, or ACE.

With 180 teachers nationwide, the program is similar to the bigger and better-known Teach for America, but with a faith-based twist. The goal: to train future educators specifically for Catholic schools, which are dealing with declines in enrollment and aging staff. The hope is to help revitalize those schools, so long and so proudly the cornerstone of urban education, and maybe even boost the faith itself.

ACE teachers in service spend two years in the program, earning classroom cred and making lasting friendships.

“Catholic schools in a sense are the future of the church,’’ said Horton, who will finish the program in June with a master’s in education, teaching credentials and a plan to work in Catholic schools. “What ACE is doing, it’s really a noble mission because these schools serve such an important role.’’

It’s a task that comes as the country struggles to answer big questions about education, said Amy Wyskochil, director of operations for the service program and a former ACE teacher. The alliance also trains future Catholic school principals, and it partners with local dioceses to strengthen their schools’ academics, enrollment and leadership.

Brianna Hohman teaches second-graders at St. Joseph's Catholic School in Tampa. She loves the job, but plans to pursue a different field after graduation.

"Education is the most important challenge facing our country,'' Wyskochil said. "Each year, millions of students fail to reach their potential because they lack access to a quality education. Catholic schools are a critical part of how we will solve our country's educational crisis. We need talented, committed new teachers to meet that challenge by becoming Catholic school teachers.''

Horton, a lifelong Catholic school student, started teaching at Holy Family last year. The school, with 204 students in K-8, has maintained a steady enrollment thanks to a healthy parish, said Sister Flo Marino. But when veteran teachers started to retire four years ago, the superintendent signed on with ACE.

“We just felt that it was a great opportunity to have young, vibrant, interesting people taking on the job of education,’’ said Marino, the only remaining religious sister at her school. “It gives schools that opportunity to revive their programs.’’ (more…)

Students know their priorities the moment they enter St. Joseph Catholic School. A sign by the front door reads, “Our Goals: College. Heaven.’’

Inside the West Tampa school’s cafeteria, boys and girls gather for Holy Karaoke, a morning program that encourages them to dance and sing, and focus on the lessons ahead.

Cartoon pumpkins belt out “Blue Moon’’ while bobbing across a giant movie screen. Sister Nivia Arias, in full habit, croons along at the pulpit before prompting her charges to recite daily affirmations.

“We are active learners who do our best work every day,’’ little voices say in unison. “We do the right thing at the right time.”

The saying sums up the philosophy of this 116-year-old parochial school once run by Salesian nuns. It may also be prophetic.

Like other Catholic schools across the nation, St. Joseph struggles with limited resources while trying to attract students and teachers. But a new partnership with the Diocese of St. Petersburg and the University of Notre Dame might be the right thing at the right time.

St. Joseph and another local Catholic school, Sacred Heart in Pinellas Park, are among five schools in the nation taking part in the Notre Dame ACE Academies, a pilot program in conjunction with the university's Alliance for Catholic Education that aims to strengthen Catholic schools and the communities they serve.

The idea is to boost enrollment and help schools develop better leadership, curriculum, instruction, financial management and marketing. (more…)

Do charter schools anchor an urban neighborhood the way catholic schools do? Not according to two researchers from the University of Notre Dame Law School. Professors Margaret F. Brinig and Nicole Stelle Garnett studied catholic and charter schools in Chicago to see how they function as urban community institutions. Why this focus? "Catholic schools are vanishing from the urban neighborhoods where they have operated for decades -- in some cases, for over a century -- and are being replaced by educational institutions so new that they did not exist anywhere in the United States two decades ago," the authors write in a report bound for the University of Chicago Law Review. "Yet virtually nothing is known about the impact that the transition will have on urban neighborhoods, many of which already struggle with disorder, crime, and poverty."

Would any school have an effect on what ails an urban community? Brinig and Garnett argue no. Relying on police "beat" data from the Chicago Police Department, the researchers found that beats with open Catholic schools have lower rates of serious crime than those without one. "Usually," the study concludes, "the presence of a charter school in a police beat appears to have no statistically significant effect on crime rates ..."

This is important in any debate over school choice, the professors say, because charter schools are seen as the more politically palatable policy alternative. "But, our findings that Catholic schools apparently anchor and stabilize struggling urban neighborhoods -- and that charter schools do not -- bolster the case for expanded school choice."

They continue:

If education policy continues on its current course, which favors an expansion of public school choice and charter schools and disfavors private school choice programs like vouchers and tax credits, then charter schools will continue to open, and Catholic schools will continue to close, in our cities ...

... At this point, we cannot know how charter schools will perform as community institutions over the long hall. But, we do know how Catholic schools are performing today and strongly suspect that further school closures likely will further erode the social capital that they generate. We also know that it is likely that multi-pronged approach to school choice, which includes financial assistance to students attending private schools might stem the tide of Catholic school closures by increasing their accessibility to students of modest means.