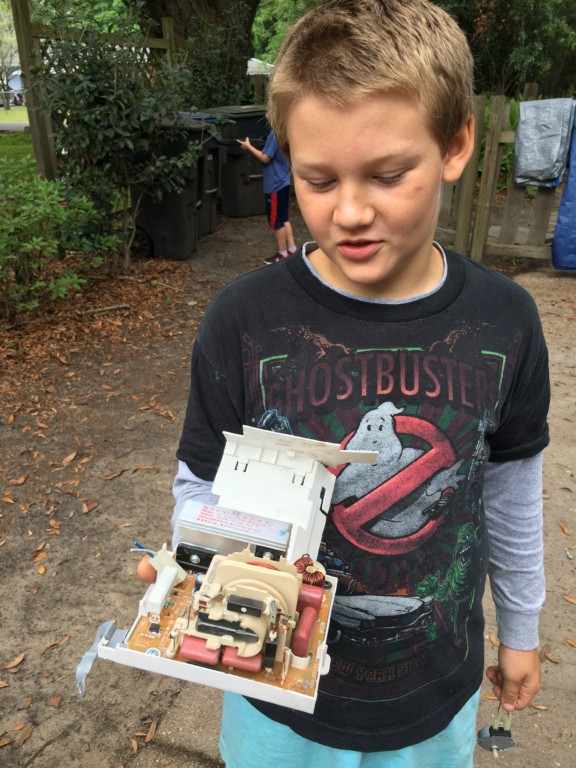

Cyrus Grenat, 10, had fun liberating this component from some gizmo during his "Taking Things Apart" class at the Magnolia School in Tallahassee, Fla. Cyrus attends thanks to a school choice scholarship.

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

With a few deft twists of a screwdriver, Cyrus Grenat, 10, detached one gizmo from an old microwave and another from a vacuum cleaner. At The Magnolia School in Tallahassee, Fla., this is school work.

Cyrus isn’t tested or graded in “Taking Things Apart,” an elective of sorts where out-of-commission radios, smart phones and other gadgets are sacrificed to curiosity.

His tiny private school doesn't do those things. It doesn’t assign much homework either. But once Cyrus gets home, the kid with the gears-turning grin and Ghostbusters T-shirt is planning to blow torch the copper out of one of his liberated components, and see if the other can be retrofitted for use in a remote-controlled car.

“It’s just fun,” Cyrus said. “I learn what’s in stuff, and how stuff works.”

With school choice in the national spotlight like never before, kids like Cyrus and schools like Magnolia could offer a lesson in how vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts work.

And who benefits.

The K-8 school in a leafy, working-class neighborhood resists political labels. (I wish we all did.) But every year, its 60 or so students “adopt” a family affected by HIV. Its middle schoolers participate in a camping trip called EarthSkills Rendezvous. Nobody has issues with which bathroom the transgender student uses, or the school’s enthusiastic participation in National Screen-Free Week.

“We are definitely different,” said director Nicole McDermott, in an office barely bigger than Harry Potter’s bedroom under the stairs. “There are kids on the playground right now who are neurotypical, playing with kids who have autism, with kids who have social issues, with kids who have all kinds of differences. We are inclusive and diverse.”

School choice makes it even more so. The Magnolia School participates in three private school choice programs – the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for low-income students, the McKay Scholarship for students with disabilities, and the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome.* About half the students at Magnolia use them.

That has made the school and its approach accessible to a wider array of families, said Susan Smith, the school’s founder. They, in turn, have enriched the school.

“This gives us the opportunity to reach further outside our little walls, so that our community reflects more of the community our children are going to grow up in, and work in, and make their families with,” said Smith, who has master’s degrees in humanities and elementary education. “It’s part of learning. Not just who you meet, and know, but who you solve problems with, and grow up with.”

The dominant narrative about choice would have America believe it’s a boon for profiteers, a crusade for the religious right, an ideological assault on a fundamental pillar of democracy. But if critics, particularly on the left, took a closer look, they’d see a more lively story – and one that has always included progressive protagonists. “Alternative schools” like Magnolia are among them, and there’s no reason why, with expanded choice, an endless variety of related strains couldn’t bloom. (more…)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, the American left cheered Freedom Schools and free schools, condemned education bureaucracies, and raised a clenched fist for community control of public education. It didn’t hesitate to think big on school choice, either.

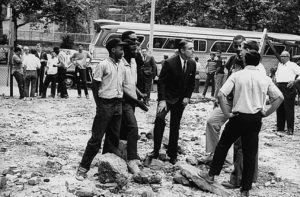

A few decades ago, some on the American left viewed school choice as a potential tool for expanding opportunity and promoting equity. An all-star academic team led by Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks pitched one such proposal with funding from the Office of Economic Opportunity, which was formed to fight President Johnson’s War on Poverty and led by Sargent Shriver (pictured at center, above). Image from sargentshriver.org

Adjusting for inflation, Ted Sizer’s 1968 proposal for a $15 billion federal voucher program for low-income kids would ring up $105 billion today – making President Trump’s still-fuzzy $20 billion idea pale in comparison. A decade later, Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman fell short in their bid to bring universal school choice to California, but their gutsy campaign still punctuates a historical truth: school choice in America has deep, rich roots on the left.

Some of today’s progressives are enraged about the suddenly serious possibility of school choice from coast to coast. True, Trump’s touch makes progressive support unlikely. True, many conservative and libertarian choice supporters raise their own, more thoughtful concerns. But it’s still stunning to see how much progressive views on school choice have shifted over the course of a few decades.

For skeptical but curious progressives, this 1970 proposal for school vouchers is a worthy read. It was produced by an all-star academic team led by liberal Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks, and funded by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity. That was the office, the brainchild of Great Society architect Sargent Shriver, that helped lead the charge in America’s War on Poverty.

Back then, vouchers weren’t maligned as a conspiracy to privatize public schools. Proponents, especially on the left, viewed them as a way to expand opportunity, promote equity, honor diversity, empower parents and teachers – and yes, improve academic outcomes.

The 348-page plan from the Jencks team is written in the language of social justice: Why, it asks, do we continue to call some colleges “public” when many people can’t afford them? Why do we call exclusive high schools “public” when only a few students can access them? Why are affluent parents considered competent enough to exercise school choice while low-income parents are denied?

The report brims with views like this: “ … [I]f the upheavals of the 1960s have taught us anything, it should be that merely increasing the Gross National Product, the absolute level of government spending, and the mean level of educational attainment will not solve our basic economic, social, and political problems. These problems do not arise because the nation as a whole is poor or ignorant. They arise because the benefits of wealth, power, and knowledge have been unequally distributed and because many Americans believe that these inequalities are unjust. A program which seeks to improve education must therefore focus on inequality, attempting to close the gap between the disadvantaged and the advantaged.”

The authors sorted through a wide array of potential variations on voucher design, and proposed a multi-year “voucher experiment” that would eventually be tried, sort of, in Alum Rock, Calif. Ultimately, the experiment proved a big disappointment; no district agreed to a plan that included private schools. Still, the report suggests the authors wanted a blueprint that could guide many communities, perhaps as part of a federal initiative. (more…)

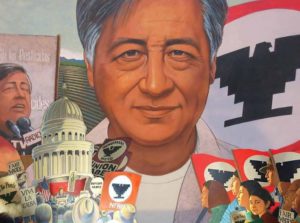

“Gradually,” Cesar Chavez predicted, “we’re going to see an awful lot of alternative schools to public education.” (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Cesar Chavez, the iconic labor leader, would have been 90 years old today, and progressives, including teacher union leaders, are pausing to honor him. But few of them probably realize Chavez’s vision of a better world – the same vision that led him to organize the most abused workers, and battle the biggest corporations – included scenes of community empowerment from earlier chapters in the school choice movement.

Chavez was a steadfast supporter of Escuela de la Raza Unida, a forgotten “freedom school” in Blythe, Calif. that sprouted in 1972, in the wake of mass parental frustration with local public schools. Some of his comments about this school in particular, and public education more generally, can be found in this rough-cut documentary about the school’s creation.

“We know public education has not … been able to deal with the aspirations of the minority group person or, in our case, our kids who have been involved with the struggle for social betterment,” Chavez tells an interviewer at about the 7:30 mark in the video.

“The people who run the institutions want everybody to think the same way, and it’s impossible,” he continued at another point. “We have different likes and dislikes, and different ideals. Different motivations. And so I’m convinced more and more that the whole question of public education is more and more not meeting the needs of the people, particularly in the case of minority group people … “

The success of Escuela de la Raza Unida is proof, Chavez said, that truly community-led schools are needed – and can work.

“Gradually,” he predicted, “we’re going to see an awful lot of alternative schools to public education.” (more…)

Karl Marx wasn't a school choice guy, as far as we know. But the guy who wrote the definitive Marxist critique of American public schools is. He admits his initial resistance to school choice was purely knee-jerk. (Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

If they wanted to, it’d be easy for progressives who oppose school choice to find a long list of other progressives who embrace it. Given the stuff that’s flying in an effort to tar Betsy DeVos, I wish more wanted to. But hope springs eternal, so today we’re hoping fair-minded progressives might pause long enough to hear from Herbert Gintis, an economist who co-wrote “Schooling in Capitalist America,” a classic in progressive education circles.

Essentially, Gintis wrote in 2004, in the foreword to another left-leaning book, “The Emancipatory Promise of Charter Schools: Toward a Progressive Politics of School Choice,” anti-school-choice progressives (who by and large are white, middle-class progressives) should stop being so knee-jerk about their education politics.

Like, at one time, Gintis admits in the foreword, he was:

When I wrote ‘The Political Economy of School Choice’ for Teachers College Record some ten years ago, my progressive friends thought I had lost my sense of reason. Everyone knew that school choice was a conservative plot to finance the private education of the well-to-do, to bleed the public schools of needed revenue, and to add one more roadblock against the struggle for social equality. Indeed, when I started writing about education in the 1970s, I shared this view. Not that I had ever really thought about the matter. I just knew if Milton Friedman (the conservative University of Chicago economist) was for it, and the teachers union were against it, I must be against it, too.

Well, we were all very wrong.

Gintis isn’t as well known in education circles as he used to be; his broad academic pursuits have taken him in other directions. But young Gintis was radical left – a member of Students for a Democratic Society, a co-founder of the Union of Radical Political Economists. “Schooling in Capitalist America,” published in 1976, was described at the time as “a genuinely creative attempt to develop a Marxist point of view about the interaction between schooling and the labor market.” Gintis theorized that American schools evolved to turn students into productive workers, not to promote equal opportunity and social mobility. In a nutshell, a factory economy needed factory schools.

Gintis’s book is still in circulation. In some corners, it still gets positive reviews. Gintis, for the most part, still stands by it. (“What we were wrong about,” he told me by phone, “is we thought there was an alternative called socialism. But there isn’t.”)

I don’t know enough about the subject to have a meaningful opinion. But I find Gintis’s take on the politics of school choice refreshing. (more…)

Before he became one of the most prolific and thoughtful school choice advocates in America, Jack Coons was a law professor who did what he could to promote civil rights in the 1960s.

His work on potential legal snags with boycotts led to a meeting with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. His conscience led him to Selma. He participated in demonstrations in Chicago after violence erupted over calls for fair housing.

Those experiences helped fuel the sustained push for school choice that Coons and fellow Berkeley law professor Stephen Sugarman began in the late 1960s and continue to this day. Much of it is detailed for the first time in a fresh set of recorded interviews for Berkeley’s Oral History Center.

The civil rights movement “certainly enhanced my spirit for the job,” Coons told interviewer Martin Meeker, the center’s associate director, for a 165-page transcript. “The work that Steve Sugarman and I have done over the years has been very much animated, I think, by our feeling about its application to families who just haven’t got any authority over their children, because they don’t have any money. They have to send them to some kind of school, that’s required, and so they have to send them to the local public school, which is a junk pile, intellectually and socially. Forgive me for all the good schools in the country that just got defamed, but it’s very much driven our interests.”

Readers of redefinED know Jack Coons. Now 86, he has written dozens of posts, echoing themes he sowed and cultivated over a half-century. Nobody emphasizes parental empowerment as a primary impulse for choice in education more than Coons. Nobody’s better at highlighting the implications for schooling and everything else.

Berkeley’s Oral History Center interviews folks who have made history or been witnesses to key events in California, the West and across America. It’s an honor for Coons to have been selected.

Sugarman is honored, too, with an interview that also sheds light on an earlier era in the choice movement – and how curiously at odds it is with current, common perception.

Critics and the press often suggest school choice is solely a Milton Friedman-inspired impulse from the “right.” Those on the “left” who give the Coons and Sugarman interviews a read will find worldviews not too different from their own. (more…)

The Netherlands decided nearly a century ago to end long-running religious strife over schools and let 1,000 flowers bloom. The Dutch system of universal school choice gives full government funding to public and private schools, including all manner of faith-based schools. (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

By common definitions, the Netherlands is a very liberal place. Prostitution is legal. Euthanasia is legal. Gay marriage is legal; in fact, the Netherlands was the first country to make it so. Marijuana is not legal, technically, but from what I hear a lot of folks are red-eyed in Dutch coffee shops, saying puff-puff-pass without looking over their shoulders.

Given the rep, it might surprise school choice critics, who tend to consider themselves left of center, and who tend to view school choice as not, that the Netherlands has one of the most robust systems of government-funded private school choice on the planet. Next year the system will reach the century mark, with nearly 70 percent of Dutch students attending private schools (and usually faith-based schools) on the public dime.

By just about any measure, the Netherlands is a progressive’s paradise. According to the Social Progress Index, it was the ninth most progressive nation in 2015, down from No. 4 in 2014. (The U.S. was No. 16 both years.) On the SPI, it ranked No. 1 in tolerance for homosexuals, and No. 2 in press freedom. On another index, the Netherlands is No. 1 in gender equality. (The U.S. is No. 42.) It’s also among the world leaders in labor union membership (No. 19 in 2012, with 17.7 percent, eight spots ahead of the U.S.). And by some accounts, Amsterdam, the capital, is the most eco-friendly city in Europe.

Somehow, this country that makes Vermont look as red as Alabama is ok with full, equal government funding for public and private schools. It’s been that way been since a constitutional change in 1917. According to education researcher Charles Glenn, the Dutch education system includes government-funded schools that represent 17 different religious types, including Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Rosicrucian, and hundreds that align to alternative bents like Montessori and Waldorf.

Glenn, an occasional contributor to redefinED, has written the book on the subject. He calls the Netherlands system “distinctively pluralistic.” (more…)

In 1968, Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks, then a leading light of the Voucher Left, argued for universal school vouchers, primarily to benefit black students: " ... for those who value a pluralistic society, the fact that such a solution would, for the first time, give large numbers of non-Catholics a choice about where they send their children, ought, I think, to outweigh all other objections." (Image from www.hks.harvard.edu)

This is the latest installment in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

School vouchers won’t drain money from public schools, won’t violate the Constitution, and won’t fray the social fabric. Ultimately, they should be supported by “those who value a pluralistic society.” So wrote liberal Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks, once a leading light on the Voucher Left, in a lengthy 1968 essay in the New York Times Magazine.

Oh, how times have changed.

Too many of today’s progressives boo and hiss at school vouchers, thinking they’re a Koch brothers weapon to kill public education. They should be reminded, as often as possible, that some of their left-of-center brethren (like him, him and him) see vouchers through a radically different lens and that, in fact, this progressive view goes back decades.

Jencks’s 1968 essay, “Private Schools for Black Children,” is yet more evidence. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Jencks led the team that tried, as part of a federal experiment, to field-test school vouchers in a California school district. He concludes in his NYT piece that vouchers are necessary for political reasons, even if he doubts it will move the ball academically for black students.

Today’s school choice supporters would respectfully disagree on the academic piece, and they have the benefit of evidence (like this, this and this) that wasn’t there 50 years ago. Also and obviously, there are plenty of other good reasons to restore parental power over education, like those thoughtfully laid out by Berkeley Law Professor Jack Coons.

Conclusion aside, what’s striking about Jencks’s essay is how he brushes aside so many anti-choice arguments that so many modern progressives embrace.

Don’t school vouchers defy constitutional restrictions separating church and state? No, Jencks says. At the time of his essay, the U.S. Supreme Court hadn’t ruled on that question. (It would, in favor of vouchers, in 2002). But, writes Jencks, it’s reasonable to think there wouldn’t be constitutional objections as long as the vouchers are “earmarked to achieve specific public purposes … “ Public money flows to Catholic hospitals and Catholic universities, he notes. Why not Catholic K-12 schools? The selectivity question continues to dodge scrutiny. (more…)

Soft-spoken and reserved, Parks did not want a big to-do about her proposed charter school. She simply wanted to help kids in her neighborhood, and she was uneasy with the possibility the school could become “political.” (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

This is the latest installment in our occasional series on the center-left roots of school choice.

If the full, rich history of school choice wasn’t so hidden, perhaps it’d be less shocking to stumble on a link (hat tip: Chris Stewart) between charter schools and “the first lady of civil rights.” But since so much of that history remains off radar, I have the honor of amplifying the blip.

Rosa Parks liked school choice, too.

In the late 1990s, she and her foundation applied for a K-12 charter school in Detroit in the hopes of uplifting black students in tough neighborhoods. Bad timing and twisted ed politics apparently doomed the effort, but it’s clear Parks, the product of a private Christian school, saw value in giving parents more options.

Said the application:

The mission of the Rosa and Raymond Parks Academy for Self Development (the “Academy”) is to provide mentoring and alternative learning, through creative education techniques, that incorporate the philosophies of Rosa and Raymond Parks. The Principles are based on their life experiences of pride, dignity and courage. Students will be educated and trained in a community environment to transfer common sense and survival skills into leadership and marketable skills.

The Academy will also provide training in life skills that incorporate the philosophies of Rose and Raymond Parks: dignity with pride, courage with perseverance and power with discipline.

Parks and her husband moved to Detroit in 1957, not long after her quiet act of courage on that Deep South bus sent dominoes falling. Their Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development operated an after-school program that stressed character education. Parks wanted a school that did the same.

Pride, dignity and courage "were the words that were important to her, and that she wanted translated into a bigger educational program,” said Anna Amato, an education consultant who worked with Parks on the application and hasn’t talked publicly about it for nearly 20 years.

The Rosa Parks charter school also planned to emphasize project-based, experiential learning. For instance, students would take field trips to Michigan “stops” on the Underground Railroad and use that as a springboard for lessons in reading, writing, history - and more.

"Our students and parents, as an entire family," said the application, "will be provided opportunities to develop a thorough knowledge of the history of the African American struggle for civil rights, along with a sense of responsibility for themselves and their communities."

Soft-spoken and reserved, Parks did not want a big to-do over the school, Amato said. She just wanted to help kids in her neighborhood, and was uneasy with the possibility the school could become “political.”

Of course, the idea that low-income parents should have options beyond district schools has become ridiculously political. (more…)

This is the latest in our series on the Voucher Left.

Five years after his death, we’re still talking about Steve Jobs. The 2015 movie about him just won two Golden Globes, including one for Aaron Sorkin’s script. His quotes still spur stories. His connection to the San Francisco 49ers somehow inspired an angle for Super Bowl 50.

So now seems as good a time as any to highlight (as other folks rightly did after his death) that Jobs, the Apple visionary, was a passionate supporter for school vouchers, and to add what hasn’t been explicitly noted, which is that he was, by conventional perceptions, an especially liberal one.

Skeptical? Jobs, the adopted son of a repo man, took a deep, lifelong dive into Eastern religions. He cultivated an organic garden. He was pretty much vegan (and at one point, a fruitarian). In his younger days, he dropped a lot of acid, dropped out of college and went to work barefoot. For years, he avoided deodorant. His company was all in for gay rights. He couldn’t get enough of Bob Dylan. And the kicker to his most famous speech, his 2005 commencement address at Stanford, was a quote from the crunchy-granola “Whole Earth Catalog.”

To be clear, I don’t care if Jobs was “conservative” or “liberal.” But tribal politics being what they are, I know many people do put stock in labels, including folks on the left who have somehow come to believe that expanding opportunity through school choice is out of synch with their “progressive” values. So, for them, it’s worth noting what Jobs, this counterculture kind of guy, had to say about school choice:

I believe very strongly that if the country gave each parent a voucher for $4,400 dollars that they could only spend at any accredited school several things would happen. Number one schools would start marketing themselves like crazy to get students.

Secondly, I think you'd see a lot of new schools starting. I've suggested as an example, if you go to Stanford Business School, they have a public policy track; they could start a school administrator track. You could get a bunch of people coming out of college tying up with someone out of the business school, they could be starting their own school. You could have 25-year-old students out of college, very idealistic, full of energy instead of starting a Silicon Valley company, they'd start a school. I believe that they would do far better than any of our public schools would. The third thing you'd see is I believe, is the quality of schools again, just in a competitive marketplace, start to rise. Some of the schools would go broke. A lot of the public schools would go broke. There's no question about it.

It would be rather painful for the first several years, but far less painful I think than the kids going through the system as it is right now. The biggest complaint of course is that schools would pick off all the good kids and all the bad kids would be left to wallow together in either a private school or remnants of a public school system. To me that's like saying "Well, all the car manufacturers are going to make BMWs and Mercedes and nobody's going to make a $10,000 car." I think the most hotly competitive market right now is the $10,000 car area.

It’s worth reading Jobs’ remarks about public education in full (thanks to the Heartland Institute for culling them), because he also says interesting things about unions, monopolies, parents and consumers. For now, a few things worth noting …

First, as Jay P. Greene pointed out after Jobs died in October 2011, the Apple CEO made similar comments as late as 2007. So these snippets above, from a 1995 interview with the Smithsonian Institution, aren’t an anomaly.

Second, Jobs came of age in an era where parental choice wasn’t saddled as it is now with the “right wing” label slapped on by critics and sealed by the press. In fact, he and Cupertino, Calif.-based Apple would have been right there, at the epicenter of a voucher quake, when liberal Berkeley law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman led a late ‘70s effort to make school choice the law of the land in California. (more…)

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)