TALLAHASSEE – Bills that would align two scholarship programs for lower-income students, speed the opening of charter schools, and make it easier for private high school students to participate in college dual enrollment programs all won approval from the Senate Education Committee Tuesday.

SB 1220, a bill that spells out rules for teacher training and qualifications, was approved and will be reported favorably out of the committee. It now includes an amendment proposed by Education Committee chairman Manny Diaz, R-Hialeah. The amendment adds provisions aimed at aligning application and eligibility guidelines between the new Family Empowerment Scholarship, adopted last year and serving 18,000 students, and the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, created in 2001 and serving 108,000 students.

SB 1420, sponsored by Deputy Majority Leader Anitere Flores, R-Miami, would require school districts to let charter schools with approved applications open the next school year.

SB 1246, sponsored by Sen. Kelli Stargel, R-Lakeland, would prohibit colleges and universities from charging fees to private schools with students who participate in dual enrollment. It also would establish a scholarship fund to help colleges cover the costs. Additionally, the bill clarifies that home schooled students are allowed to participate in dual enrollment programs at no cost to their families.

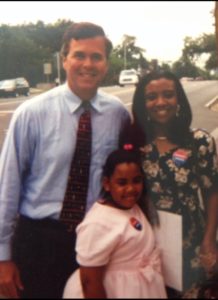

Tracy James and her daughter, Khaliah Clanton-Williams, are greeted by principal Maria Mitkevicius and administrator Mary Gaudet at the Montessori School of Pensacola. Khaliah

participated in Florida's Opportunity Scholarship program in early 2000. PHOTO: Michael Spooneybarger

Editor’s note: During this holiday season, redefinED is republishing our best articles of 2019 – those features and commentaries that deserve a second look. This article from Step Up For Students’ director of policy and public affairs Ron Matus was part of our “Education Revolution” series marking the 20th anniversary of the far-reaching K-12 changes Gov. Jeb Bush launched in Florida. Originally published May 30, it spotlights a mom and daughter who participated in Florida’s historic Opportunity Scholarship.

PENSACOLA, Fla. – Tracy James finished the graveyard shift to find her car a casualty of the “voucher wars” – and her 8-year-old, Khaliah, needing another ride to school.

This was 20 years ago, when this Deep South Navy town became the front in the national battle over school choice. In June 1999, Florida’s new governor, Jeb Bush, had signed into law the Opportunity Scholarship, the first, modern, statewide, K-12 private school voucher in America. Khaliah and 56 other students in Pensacola were the first recipients, and now enmeshed in a political clash drawing global attention.

CNN came. A Japanese film crew showed up. So did a member of British Parliament. All wanted to see the “experiment” a Canadian newspaper said “will shape the future of public education in this state and perhaps across the United States.” Tracy and Khaliah were in the thick of it, with Tracy among the most outspoken of an unconventional cast of characters. The single mom with the self-described rebel streak wouldn’t hide her joy at this opportunity for her only child – and refused to cave to anybody who suggested she was being “bamboozled.”

“If you want something better for your children,” she told one paper, “you would do the same thing.”

Not everybody appreciated her resolve.

Tracy walked out of her shift as a phlebotomist to find her car sabotaged, three tires flat as week-old Coke. She called her dad, who said he could take Khaliah to her new school, one Tracy could not afford without the scholarship. The flats left Tracy shocked and ticked – and more determined.

I guess I need tougher skin, she thought. Because we ain’t going back.

Lots of folks know Ruby Bridges. But Khaliah Clanton-Williams? Maybe one day.

The original Opportunity Scholarship students, their parents, and the five private schools that welcomed them have never gotten their due. After an epic legal battle, the Florida Supreme Court ruled the school choice program unconstitutional in 2006, and the decision in Bush v. Holmes seemed to close the chapter. But it didn’t. Many of those whose lives were touched by the scholarship have untold stories, with some still unfolding in ways that attest to the power of that experience.

In one sense, the Opportunity Scholarship was as small-scale as it was short-lived. Students were eligible if their zoned public schools earned two F grades in a 4-year span, and in 1999 only two schools – both in Pensacola – fell into that category. At the same time, most private schools sat it out. Among other restrictions, the law barred them from charging tuition beyond the scholarship amount of $3,400 to $3,800. At its height, the Opportunity Scholarship served 788 students.

And yet, it loomed so large. Florida’s “first voucher” stirred the imagination about what could be with a more pluralistic, parent-driven system of public education. It exposed the festering dissatisfaction many parents had with assigned schools. It enabled and amplified voices that still aren’t heard enough.

Pensacola may be best known for its Blue Angels and sugar-sand beaches. But most of the parents who applied for the school choice scholarships were working-class black women – nursing assistants and bank tellers, cooks and clerks, Head Start workers and homemakers. They had a lot to say about schools in Pensacola’s low-income neighborhoods, and for a few months in 1999, they had the mic.

***

Khaliah’s assigned school was modest red brick, five blocks from her home, named for the district’s first “supervisor of colored schools.” Khaliah would be starting kindergarten, so Tracy stopped to visit. She never got past the front office. “It was a zoo,” she said. “Kids were running around. They were screaming. There was no discipline. There was no structure.”

Nobody with the school acknowledged her, so after a few minutes, Tracy left … for good. She turned to her only option: another district school near her mother’s house, two miles away. Tracy said her mom, a former custodian for the school district, became Khaliah’s guardian so Khaliah could attend. But that school didn’t pan out either.

One day, Tracy watched through a window as kids in Khaliah’s class danced to music blaring from a boom box. She found the teacher in a side office and asked what was going on: “ ‘She said, ‘It’s reading time.’ I said, ‘They’re not reading.’ “ Tracy opened her eyes wide for emphasis.

Khaliah, meanwhile, shy and soft-spoken, was falling behind. “I had a hard time concentrating because it was so loud,” she said. “I’d ask for help and it was like, ‘just a moment.’ But the moment never came.”

Tracy heard about Opportunity Scholarships while working another job as a hotel desk supervisor. Some guests asked her in passing about local schools, and as fate would have it, they were lawyers with the Institute for Justice, the firm that would later help defend the scholarship in court.

Ninety-two students applied for the scholarships, including Khaliah, who had come back to live with Tracy. That exceeded the available seats in the four Catholic schools and one Montessori that opted to participate, so a lottery was held.

Khaliah emerged with a golden ticket.

***

Tracy took her time before deciding on a school. She read up on Catholic schools, talked to friends and co-workers who attended Catholic schools, learned everything she could about Montessori. She was intrigued by the latter – by the mixed-age classrooms, the cultivation of creativity, the curriculum that was so different. In the end, the rebel and her daughter decided they wanted different.

Khaliah Clanton-Williams, left, used an Opportunity Scholarship to attend the Montessori School of Pensacola.

Khaliah attended Montessori School of Pensacola from second through seventh grade, and, in Tracy’s words, “blossomed” in confidence and knowledge. She returned to public school in eighth grade (Tracy wanted her re-acclimated to public school before high school) and graduated from Pensacola High in 2010. For most of the next few years, she worked as a mortgage loan officer. She earned her associate degree in business administration from Pensacola State College in 2018. She’s on track to earn a bachelor’s in human resources management (with honors) in 2020.

Without the Montessori, Khaliah said, much of that would not have happened.

“It made me better,” she said. “I don’t think I would have gone to college. I don’t think I would have gotten my degree. (Montessori) made education more important. It was a higher standard.”

The upside wasn’t just academic. Tracy and Khaliah said nearly everyone in the school embraced Khaliah as family. There were only a few black students before a few more enrolled with the scholarships, but race was not a divide, they said. Khaliah made fast friends. They invited her to sleepovers, to ride horses, to U-pick blueberries. “These things were normal to them, but not to me,” she said.

Montessori co-owner (and head of elementary and middle school) Maria Mitkevicius said increasing diversity was a big reason the school opted into the scholarship program. So was the belief the school shouldn’t be limited to parents of means.

The staff knew the stakes, even if they didn’t know how much things might change. Twenty years after five private schools and 57 kids cracked the door, at least 26 private schools in Escambia County (Pensacola is the county seat) participate in Florida’s K-12 school choice scholarship programs, serving at least 2,163 students. Statewide, 2,000 private schools serve more than 140,000 scholarship students, with thousands more on the way.

“We thought this might change the face of education,” Mitkevicius said. “I guess it did.”

***

The news on Pensacola TV showed 10,000 sign-waving students and parents, marching at a 2016 school choice rally in Tallahassee with Martin Luther King III. As Khaliah watched it again last week, tears fell.

It hurt, she said, to see so many who still don’t have choice or fear their choices could be taken from them. At the same time, how nice to see strength in numbers.

“Back then,” she said, meaning 1999, “it was just us.”

Tracy James and her daughter, Khaliah, with former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush circa 1999.

Remembering back then is tough for Tracy too. Some in Pensacola’s black community could not understand why black parents would support anything connected to Jeb Bush. “We were looked on as kind of those people who are being arm twisted by the governor, like you’re letting the Republicans bamboozle you,” said Tracy, now a clinical recruiter for a Pensacola hospital.

It got ugly. Dirty looks. Heated words. The tires. Tracy said some friends and family stopped speaking to her, and she switched jobs because she felt she was being harassed for taking a stand.

But the rebel has no regrets.

“I wanted to try something different, I wanted to be different, I wanted a different opportunity for my daughter,” Tracy said. “From what I saw happening, I wanted to be able to make the choice, myself, of where she’d end up as an adult.”

“I had no idea that it’d turn out to be such a controversial issue,” she continued. “To be thrown into sort of the limelight of a political battle, I had no idea. I had absolutely no idea how important it would be.”

Or how much of a struggle.

“When we went through that program, I was thinking that was kind of the end of an era,” Tracy said. “But it was actually the beginning.”

***

The shy girl who helped pioneer school choice is now a tough-minded mom who needs more.

Khaliah is married to a paper mill machine operator, and their oldest, Kyrian, will begin kindergarten this fall. His zoned school is one of 11 D-rated schools in the district, so like her mom before her, Khaliah looked for alternatives. She applied to three higher-performing district schools through an open enrollment program, but all were full. On a second go-round, Kyrian got into a new elementary north of Pensacola. It’s not ideal. The drive will be up to 45 minutes each way, and Khaliah switched jobs – to drive for Shipt, Lyft and Uber – so she can have flexibility.

Still, she’s worried. Kyrian has special needs – he’s hyperactive, averse to change in routine and undergoing speech therapy – but has not been formally diagnosed with anything. At this time, he wouldn’t qualify for any of Florida’s private school scholarships.

The irony isn’t lost on Tracy and Khaliah. School choice helped them. They helped pave the way for more. Yet 20 years later, there still isn’t enough choice for Kyrian.

The rebel’s daughter said that just means the work isn’t done.

“I’ll continue to fight for my children as my mom fought for me,” Khaliah said. “I’m not taking no as an option.”

Editor's note: Each Saturday in November, redefinED is reprising a podcast from our archives, reminding readers that we have a wealth of audio content to complement our written blog posts. Today, we revisit a September 2015 interview with a voucher advocate who has fought for the educational rights of disabled and low-income students.

Editor's note: Each Saturday in November, redefinED is reprising a podcast from our archives, reminding readers that we have a wealth of audio content to complement our written blog posts. Today, we revisit a September 2015 interview with a voucher advocate who has fought for the educational rights of disabled and low-income students.

Marcus Brandon’s resume starts off like a progressive’s dream.

National finance director, Dennis Kucinich for president. Staffer, Progressive Majority. Deputy director, Equality Virginia. But once it rolls into Brandon’s education accomplishments, some fellow progressives get whiplash. During two terms in the North Carolina House of Representatives, Brandon was a leading force behind bills that created vouchers for disabled and low-income students, and removed the state’s cap on charter schools.

Inconsistency? Not for Brandon, a rising political star whose family’s civil rights bona fides are unquestioned.

“I tell people that my views on education are the most progressive stance that I have,” Brandon told redefinED. “Progressives have to take a real hard look at the way they view education because I’ve always been brought up, in the civil rights movement and all of that, (to) fight for equal opportunity and equal access for everybody.”

Brandon, who now directs the Carolina CAN education advocacy group, isn’t an anomaly. A growing list of influential liberals, progressives and Democrats are increasingly supportive of school choice. In the process, they’re wrenching the left back into alignment with its own forgotten history – a history that is especially rich in the African-American experience.

Milton Friedman would merit a few paragraphs in a book on this subject. But there’d be whole chapters devoted to the educational endeavors of freed slaves and black churches. To Mississippi freedom schools and Marva Collins. To the connections between Brown v. Board of Education and Zelman v. Simmons-Harris.

“School choice is not new for African-Americans,” said Brandon, whose family played a role in the lunch counter sit-ins in Greensboro, N.C., which toppled segregationist dominos nationwide. “It is very much a part of our history for the community to be involved with the school. It’s very much a part of our history for the churches to start their own school. That is just as deep in our history as any part of our history. … It mind-boggles me that the people who are fighting this will forget that.”

The evidence is in plain sight. A who’s who of black Democrats have explained their support for school choice in many ways, in many forums (see here, here, and here for starters). Progressives who are still skeptical should consider James Forman Jr.’s paper, “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First.” Or check out the annual gathering of the Black Alliance for Educational Options. Or look at the polling, which shows deep support for school choice in black communities.

Better yet, they should pause and consider the pleas of black parents.

In the meantime, they should hear out one of their own. (A podcast with Brandon is included below.)

Brandon’s support for vouchers and charter schools led fellow progressives to threaten to run him out of office, and worse. (Those kinds of attacks on black choice supporters aren’t an anomaly either.

Consider hit pieces like this one. And headlines like this.) What they should have done instead, he suggested, was consider choice on its merits – and the hypocrisy of many choice critics.

“You get a lot of harsh rhetoric from progressives … who would never send their child to my school one day of the week. That’s why I have a problem with that,” Brandon said. “They’re like, ‘Keep your kids there, keep your kids there.’ But at the end of the day they would never send their kids to my school.

“I remember being in a parade one time, and one progressive yelled at me, ‘You’re privatizing schools.’ And I asked her, ‘Would you send your kid to my school?’ And every time I ask that question the conversation gets very silent. And so what African-Americans need to do is understand that. Our leaders need to understand that those that are leading this fight (against school choice) do not send their kids to our school. And so what are we going to do?”

It’s not progressive, he said, to keep looking the other away.

“We’ve allowed these educational outcomes and these policies to go on for 40, 50 years, and then we say we’re going to continue that and someone says that’s progressive,” Brandon said. “If you have data that shows consistently that there is one particular segment of the population that doesn’t do well under a system, well that’s not progressive.”

Actually, he said, it’s “extremely conservative.”

Julian Cruz, pictured here with his mother, Emily, was one of the first students to receive a Gardiner Scholarship for students with special needs. The direct-state-funded scholarship now serves nearly 12,000 students.

Editor’s note: We add a new feature today, called fact-checkED, that is inspired by the many factchecking efforts across the media landscape these days. Our work will focus solely within the arena of educational choice, and our goal is to bring clinical precision to issues that are often complex and misunderstood. Our intent is not to shame but to inform.

![]() In an editorial Sunday criticizing 19 “bad bills” that became state law this year, the South Florida Sun-Sentinel wrote the following of a new school voucher called Family Empowerment Scholarships:

In an editorial Sunday criticizing 19 “bad bills” that became state law this year, the South Florida Sun-Sentinel wrote the following of a new school voucher called Family Empowerment Scholarships:

“Tuition vouchers (SB 7070). For the first time, money goes straight from (the) state treasury – not just by tax credits.”

This is false.

We begin by first acknowledging that the sentence above ends with a phrase describing the money as going “to unregulated private schools, most of which will be religious and can cherry-pick their students.” That’s a handful in itself, particularly given that the participating private schools are subject to roughly 17,000 words of statutory and agency regulations and that annual state evaluations of a similar program, called the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, have concluded it draws some of the state’s poorest and lowest-performing students from public schools.

But our focus here is on the claim that the Family Empowerment Scholarship (FES) is the first school voucher to draw funds directly from the state treasury. That’s in part because the claim has current legal and political salience. Ron Meyer, attorney for the Florida Education Association, the state’s largest teacher union, has told reporters he plans to file a lawsuit asking courts to declare the new program unconstitutional. Even before the bill was passed, Meyer told the GateHouse Capital Bureau: “This could lead to the dismantling of the public school system as we’ve known it.” In June, a month after the bill was signed into law, he told the Florida Phoenix: “There is going to be a challenge.”

The Sun Sentinel editorial draws a proper contrast between the new FES program and an existing 18-year-old program called the Tax Credit Scholarship. Both serve disadvantaged students from low-income and working-class households, but the Tax Credit Scholarship is fueled by contributions from corporations. In turn, those contributions receive 100 percent credits against six different state taxes. Last year, the Tax Credit Scholarship served 104,091 low-income students at a cost of roughly $644.7 million. The funding distinction is important, and led in part to the 2017 dismissal of a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Tax Credit program.

As the editorial notes, FES is funded directly by the state. In fact, it is funded directly out of the operational funding formula, known as the Florida Education Finance Program (FEFP), that pays for district public schools. One distinct difference between FES and district schools is that the scholarships receive money only through state general revenue dollars and do not receive any local property tax money (see subsection (11)(e) in the law).

The claim of being first, though, is wrong. FES is neither the first nor the only state-funded education voucher in the PreK-12 arena. It’s not even the only voucher funded directly through the FEFP. Here are the others:

To its credit, the Sun Sentinel published a partial correction to the editorial above. We rate the original claim as FALSE.

Early in his recently published book, “How the Other Half Learns: Equality, Excellence, and the Battle Over School Choice,” Robert Pondiscio introduces the “Tiffany Test.”

Pondiscio had answered the call to teach in a district school in the Bronx after a career in publishing. One of his students, Tiffany, was dutiful and organized, and as Robert relates, purposefully neglected by the staff of her school. She passed the state accountability exam while Pondiscio’s co-workers and superiors consistently instructed him to focus entirely on the “bubble” – students on the verge of progressing – and those far below grade level.

Pondiscio acknowledges that he didn’t have much success with the “bubble” students, and that he neglected Tiffany in the process. He notes that this neglect was a purposeful choice made through public policy, and that the assumption that a student will be “fine” just because he or she passes a minimum skills test is highly questionable, creating an incentive for educators to look the other way while students fall through the cracks.

Pondiscio’s “Tiffany Test” for a proposed public policy change is straightforward: Will the proposed change be good for students like Tiffany?

By my way of thinking, there are millions of “Tiffany” students in our school system right now. There always have been, and there always will be. “Tiffany” students are dutiful scholars who find themselves neglected because they have done what they are supposed to do. “Tiffany” can be a very bright child who is horribly bored by school, following an academic program that has nothing to do with his or her academic needs.

Consider, for instance, the story of 19-year-old Taylor Wilson, who was “bored silly” in a typical school setting until a gifted educator at a Reno, Nev., high school encouraged him to indulge a dream he’d had since age 11: building a nuclear reactor.

Sadly, bullied students are far more numerous than genius students. Earlier this week, redefinED’s Ron Matus brought us the story of Elijah Robinson, a Florida student who found refuge and flourished in a private religious school after experiencing extreme bullying due to his sexual orientation at his assigned public school. When Elijah went to the adults at his school for help with the abuse, they told him to “ignore it.”

Contrast the experience of these two students with Pondiscio’s definition of a “Tiffany” – a student who buys into the promise of education but is sorely let down by the educators.

Some believe that only children in “failing” schools should receive vouchers. But if Elijah’s tormentors happened to be good at standardized testing, would it have made his life more bearable? Would it have made the indifference of the staff at his previous school somehow less damaging? Even schools with very high levels of average performance have students whose social or academic needs are going unmet. Likewise, in that same school, someone’s “problem” could be another student’s solution. Families must be allowed to sort these things out from the bottom up.

Also consider this: Sometimes “Tiffany” is a student whose teachers dismiss him or her as “not college material.” Sometimes “Tiffany” is a student with a disability whose Individualized Education Program committee members simply are going through the motions, doing just enough to avoid exposing the school to risk of a lawsuit. And sometimes an entire state education apparatus engages in a 12-year conspiracy to deny special education services to hundreds of thousands of students.

Maybe it’s a little early, maybe the time is not quite yet, but the day is coming when our K-12 policies will fully and appropriately respect the dignity of families to exercise autonomy in schooling. When that day comes, the unfulfilled, the disappointed, the mistreated, the misfit and the dreamer will seek better situations for themselves.

They won’t ask for permission, but rather will be exercising their rights as free people. Pleading with adults to do what is right won’t be the first or only option. When that day comes, “Tiffany” can speak softly, but her voice will be imperial; the system will center around her at last.

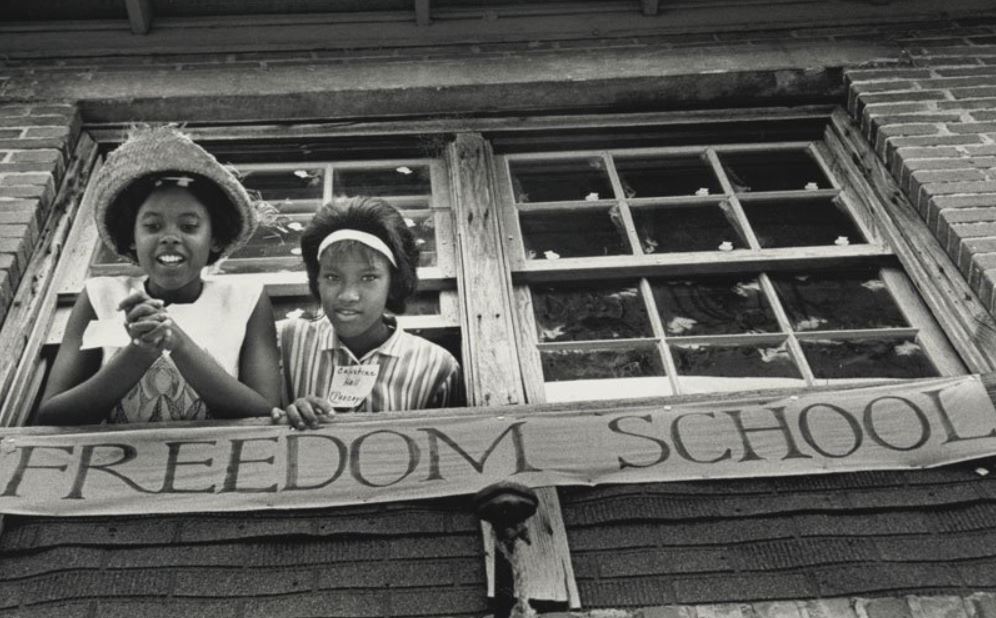

Despite what the story lines too often suggest, school choice in America has deep roots on the political left, in many camps spanning many decades. Mississippi Freedom Schools, pictured above (the image is from kpbs.org), are part of this broader, richer story, as historian James Forman Jr. and others have rightly noted.

Editor's note: Each Saturday in October, redefinED will revive a post from our archives that speaks to the rich and sometimes surprising history of education choice in the United States. Today's post, which first appeared in 2012, is nevertheless still relevant, reminding us it’s impossible to stereotype families who use vouchers and tax credit scholarships.

Think school choice is solely a conservative idea? Think again.

* After the Civil War, blacks in the South who were tired of waiting for the government to organize schools – or who were dissatisfied with the quality – built schools themselves.

* During the civil rights movement, activists in both the north and south established alternatives to segregated, second-rate schools.

* In the 1960s, leading progressives proposed private-school vouchers because of anger over failing inner-city schools.

Historical gems like these sparkle throughout “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First,” a 2005 academic journal piece by Georgetown University law professor James Forman Jr. From Reconstruction to the civil rights era to the “free schools” and “community control” movements – indeed, for most of American history – progressives have been a leading voice for choice.

So forget what you hear from choice critics and read in the newspaper. The parents who use vouchers and tax credit scholarships to help their kids can’t be shoved into one political box or another. The same goes for the political and philosophical roots that sprouted those options. Conservatives have advanced compelling reasons for school choice. So have progressives.

Writes Forman:

“School choice – especially vouchers and, to a lesser extent, charter schools – is generally understood to have a conservative intellectual and political heritage … choice is associated with free-market economist Milton Friedman, attempts to defy Brown, wealthy conservative philanthropists, and the attacks on the public school bureaucracy by Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush.”

“It turns out that conventional history is incomplete … too often missing from the historical account is the left’s substantial – indeed, I would say leading – contribution to the development of school choice. In this Essay, I trace that history, arguing that school choice has deep roots in liberal educational reform movements, the civil rights movement, and black nationalism … “

Forman doesn’t hide his agenda. He wants to give modern progressives – the source of so much passionate opposition to choice – good reason to think twice.

“While some liberals have embraced choice proposals, others have rejected them on the grounds of their segregationist heritage. The incomplete view of history has distracted some from the issue that I think matters most, which is how choice is implemented. Accordingly, understanding the history of progressive choice proposals – including even school vouchers – might offer today’s liberals a way to have a more nuanced conversation about school choice.”

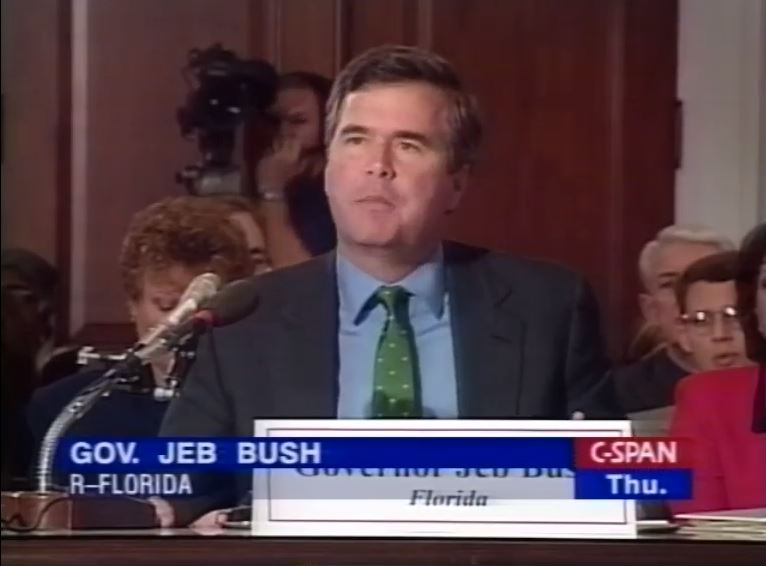

Florida's then-Gov. Jeb Bush testifying before a U.S. House committee Sept. 23, 1999.

Florida's then-Gov. Jeb Bush testifying before a U.S. House committee Sept. 23, 1999.

Twenty years ago this week, Gov. Jeb Bush spoke before the House Education Budget Committee about Florida’s recently passed A+ Plan and the state’s first voucher, the Opportunity Scholarship Program.

“It’s been fun, in all honesty,” Bush said with a smirk, “to watch the myths that have been built up over time when you empower parents.”

Those myths were shattered, Bush said, though he admitted the program was only just a few months old at that point. Nevertheless, two decades of evidence have proved him correct.

By the time of Bush’s presentation, the Opportunity Scholarship had awarded scholarships to 134 students at two schools in Pensacola. Seventy-six of those students used the program to attend another higher-performing public school, while 58 used the voucher to attend a private school, according to Bush’s testimony.

The first myth Bush called “the brain drain,” which occurs when only the high-achieving kids leave public schools. But according to Bush, the students on the program were no more or less academically advantaged than their peers who remained behind.

The second myth was that vouchers would only benefit higher-income students. “Eighty-five percent of the students are minority,” Bush said. “Eighty-five percent qualify for reduced and free lunch. This is not a welfare program for the rich, but an empowerment program for the disadvantaged.”

The third and final myth he called “the abandonment myth” -- schools where students leave will spiral ever downward.

Twenty years later these myths remain busted.

Eleven years of research on the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship show the critics’ claims ring hollow.

• Students attending private schools with the help of the scholarship are among the lowest-performing students in the public schools they leave behind.

• Today, 75 percent of scholarship students are non-white, 57 percent live in single-parent households, and the average student lives in a household earning around $27,000 a year. Researchers at the Learning Systems Institute at Florida State noted that these students are also more economically disadvantaged than their eligible public-school peers.

• More importantly, scholarship students are achieving Jeb Bush’s goal of gaining a year’s worth of learning in a year’s time.

• Even the abandonment myth remains untrue. Overall, public schools with large populations of potentially eligible scholarship students actually performed better, as a result of competition from the scholarship program, according to researchers David Figlio and Cassandra Hart.

When Jeb Bush took office just 52 percent of Florida’s students graduated. Today 86 percent of students graduate. According to the Urban Institute, students on the scholarship are more likely to graduate high school and attend and later graduate from college. State test scores on the Nation’s Report Card are up considerably since 1998 too. And when adjusting for demographics, Florida, which is a majority-minority state, ranks highly on K-12 education compared to wealthier and whiter peers.

There’s still room for improvement. But the naysayers at the turn of the century have been proven wrong.

Alberto Cruz and Ramona Ceballo

Editor's note: Each Saturday in September, redefinED is dipping into the archives to revisit a compelling story written from the perspective of a parent advocate. In today's post, a single mom explains how a scholarship for students with special needs changed her son's life, academically and emotionally.

No words can express how thankful we are for the McKay Scholarship.

I have been a single mother of four for a long time. ln the past my son Alberto Cruz struggled with the family’s marital turmoil, as well as with a speech impediment and a form of attention deficit disorder. He went from one school to another, one counselor to another.

He struggled academically and socially in class because he couldn’t find the right programs to fit him, and he failed to receive the emotional support he needed. Plus, he was intimidated by the bigger size of the traditional public schools and the crowds of students.

By age 9, my son hated school. Sometimes he would just sit by himself in a corner, not interacting with any of his peers. He could relate to few teachers.

Worst of all, he said he wanted to end his life. He said almost every day that life didn’t have sense.

For many years, we had a very hard time.

Then one day about nine years ago the director of a private school recommended that I apply for a McKay Scholarship, which is for students with disabilities. Our life has been better since we received the scholarship, which has allowed Alberto to attend The Learning Foundation of Florida, a private school in Royal Palm Beach, since the beginning of middle school.

Now, my son never complains about school. He loves the smaller class sizes, and the small groups of friends he has made. His grades have gone from F’s and D’s before the scholarship to A’s and B’s. He has studied math for college, as well as economics, leadership skills, and English IV. He can learn at his own pace – he likes that there is no hurry to finish class. He’s given a due date to complete a learning module. If he finishes it early he can move on to the next assignment. He also loves the teachers he has had and the personal attention they give him.

I have seen him change, and so have his teachers. He has made progress academically and socially, and his self-esteem is better.

Now a senior in high school, Alberto has the opportunity to go to job training, take driving lessons, receive counseling, and so much more. The McKay Scholarship is helping us — the teachers, and me, the parent — understand my son. It is helping us get Alberto where he needs to be to have a bright future!

Where he once hated school, now Alberto doesn’t want to leave school. He has developed a very strong bond with his teachers and his classmates. It will be hard for him to leave them behind. However, the scholarship is helping him to prepare to move on to a better future. Although he hasn’t settled on a post-graduation path, whatever Alberto decides to do l am confident that the McKay Scholarship will have guided him in the right direction. l am grateful for all the teachers at Learning Foundation and their hard work and dedication, and thankful for the McKay Scholarship.

Ramona Ceballo lives in West Palm Beach.

On June 7, 2005, opposing sides met for the final time to argue before the Florida Supreme Court over the constitutionality of the state’s first voucher program, the Opportunity Scholarship. Supporters of the program for low-income students had won several important victories, forcing opponents to abandon all but one remaining argument -- that the voucher violated Florida’s “Blaine Amendment.”

Florida’s Blaine Amendment, Article 1, Section 3 of Florida’s constitution, is one of the most restrictive in the country. It reads:

“No revenue of the state or any political subdivision or agency thereof shall ever be taken from the public treasury directly or indirectly in aid of any church, sect, or religious denomination or in aid of any sectarian institution.”

Just seven months earlier the First District Court of Appeal issued an “en banc” decision, with eight of the justices declaring the program violated Article 1, Section 3.*

A ruling by Florida’s Supreme Court on the matter could have sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve, once and for all, how state Blaine Amendments could be applied to restrict or support state-funded scholarships to attend religious schools. But the Florida Supreme Court ducked the issue altogether. In a stunning move, the Court reversed course and resurrected two arguments it had rejected just four years before.

The U.S. Supreme court isn’t expected to resolve the lingering questions over state Blaine Amendments until 2020.

Florida’s First District Court of Appeal had the last word on the matter, but despite claiming a “clear meaning” and “unambiguous history” of Florida’s no aid clause, the court’s decision left gaping holes and many unanswered questions.

Lawyers defending the voucher program argued the scholarship did not violate the Florida Constitution because the benefit was to the student and the general public, and not intended to aid religious organization. In fact, the entire program was neutral with respect to religion because the vouchers were issued to parents who could use them at any private religious or non-religious school of their choosing.

Furthermore, the Opportunity Scholarship forbid private schools from selecting students on a religious basis and stated that scholarship students could not be compelled to pray, attend worship or even take religious courses.

Supporters noted several state programs benefiting Florida residents were provided at religious or religiously-affiliated institutions. Programs included Florida Bright Futures Scholarship, John McKay Scholarships, Florida Private Student Assistance Grant Program and eight other scholarship programs, along with the 23 private religious colleges accepting them. Supporters pointed to direct financial support for religiously-affiliated colleges, including $8.9 million in 2002 for libraries at Bethune-Cookman, Edward Waters College and Florida Memorial College.

Attorney General Robert Butterworth pointed to other direct appropriations, such a rent paid to churches used as polling places and subsidized pre-K at religious preschools.

Butterworth even noted that state funds provided subsidized medical care at religiously affiliated hospitals such as St. Mary’s in West Palm Beach or Baptist Medical Center in Jacksonville.

A direct taxpayer subsidy to a sick patient to attend any hospital, religious or non-religious, of their choosing, should not be treated any differently under the law that a scholarship to attend a religious or non-religious school, the Attorney General argued.

The appellate court majority responded to these arguments with deafening silence, with no mention of the McKay Scholarship, the state’s only other K-12 voucher program funded by direct appropriations at the time. The ruling was narrowly tailored to only one single K-12 scholarship program.

Even Judge Wolf, who concurred in part, criticized the majorities incoherent constitutional interpretation stating,

“In order to avoid catastrophic and absurd results which would occur if this inflexible approach was applied to areas other than public schools, the majority is forced to argue that the opinion is limited to public school funding and article 1, section 3 may not apply to other areas receiving public funding.”

The court would not only fail to grapple with these important constitutional questions, it would end up ignoring Florida’s own legal precedent on the matter.

Coming Thursday: Florida has a long history of court cases that upheld the constitutionality of providing aid to religious institutions.

*Seven justices ruled the OSP should be struck down entirely for violating the state’s “Blaine Amendment.” Just one justice ruled the OSP should be partially struck down by requiring religious schools to be excluded from the program. Five justices ruled the program should be upheld.

Editor's note: Each Saturday in September, redefinED is dipping into the archives to revisit a compelling story written from the perspective of a parent advocate. Today's post features a mom who utilized a Gardiner Scholarship to provide her special needs son with educational resources he would not have received otherwise.

Editor's note: Each Saturday in September, redefinED is dipping into the archives to revisit a compelling story written from the perspective of a parent advocate. Today's post features a mom who utilized a Gardiner Scholarship to provide her special needs son with educational resources he would not have received otherwise.

We had become parents a second time. This time it was a boy.

Kevin was a vivacious, wonderful baby full of laughter and joy. His development took the usual course. He was a bit behind in language, but we were told it was of no concern yet. A littler later, however, we noticed Kevin had repetitive behaviors, was lining his toys up and, well, had a very strong “personality.”

When we sought the assistance of a speech therapist, she referred us to Early Steps, an organization to screen autism.

The day we were told our son was autistic, my husband and I were shocked by the words, but at the same time we knew.

We immediately began therapies to help his speech and decided to place him in a public school program for pre-schoolers with autism.

At the time, we were completely satisfied with his progress. We found that he adapted well to the learning environment.

However, with our move, we had to change schools. Furthermore, once he exited the pre-kinder autistic class, where there were only five children and two instructors, he was assigned to an inclusion class with 25 students and only one instructor and a “floating” inclusion teacher.

Kevin was left soiled, was not fed for over a month, and continuously eloped to the parking lot.

We finally decided to place Kevin in an ABA center to help him with his behaviors, which were seriously impeding daily life.

Since the ABA was six hours a day, we decided to register him in homeschool. At first, this was very difficult, but when I learned the Gardiner Scholarship helped families like us, we were immediately alleviated.

The Gardiner Scholarship is an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome. It has been a Godsend to our family. Not only do I have the ability to choose homeschool for my son, I have resources that I would not have been able to afford to give him otherwise.

The public sector is not a good fit for Kevin, who is now 9 years old, as his needs extend beyond what it can provide.

Now I have the tools and resources to provide my son with diverse curricula, private tutors, sensory and physical materials, and technological devices.

I attribute the great strides Kevin has made in his development to the Gardiner Scholarship. It enabled us to help him not only become verbal, but fluent.

I cannot imagine a world without Gardiner.

Ana Garcia is a mother in Homestead, Fla.