Florida’s students and parents are choosing charter schools in greater numbers, and it’s affecting districts’ bottom lines.

If recent history and current waiting lists are any indication, this is likely to continue.

The growth of charter schools (and other school choice options for that matter) over the past decade has come amid a slowdown in the growth of school districts. While that may be changing a little as new enrollment picks up again, it’s still a dramatic departure from the two decades that preceded it — the era of endless portables and 30-student elementary classrooms, when districts struggled to find space for all the new students moving from out of state.

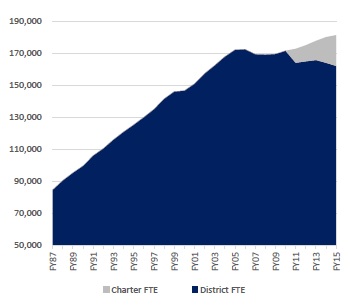

This graph from a Palm Beach County School District budget presentation (hat tip to the Palm Beach Post) tells the story.

Charter school enrollment represents a long-term threat to the district. Although charter school enrollment represents only 7% of overall enrollment, the 19.5% average annual increase in charter school enrollment since 2005 has far outpaced that of non-charter school enrollment, which has remained essentially flat over the same period. To date, the district continues to meet class size reduction mandates.

While many districts are responding by creating new programs to attract students who might otherwise have chosen other options, the way they borrow money, fund school facilities and plan for expenses has not fully caught up to this new reality.

One response has been to propose central planning systems that would restrict the growth of charter schools. Such an idea was proposed, but did not advance, in this year’s legislative session. It’s also being tried in other states, like Delaware, which is home to Wilmington, one of the most charter-saturated cities in the country. Some say that approach undermines parents’ ability to decide which schools work best.

[Michael Petrilli of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute] doesn’t believe the market for schools should be totally hands-off. He promotes rigorous accountability for charters and believes the government should play an active role in closing poor schools. It’s the idea of government gauging need and deciding where charters should open that bugs him.

“You do not want to create a situation where there is a political body that is under political control making decisions that may not be in the best interest of the consumers,” Petrilli says.

There is no question that the growth of charter schools and private-school scholarships has added complexity for school districts that must plan for enrollment growth and the new schools that are necessary to accommodate those new students.

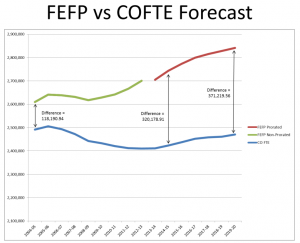

But these additional options can also create savings in both state and district capital-improvement budgets. The chart below is from a presentation earlier this month at the Florida Educational Facilities Planners’ Association summer conference, and it reflects a beneficial trend. It shows that the need for district capital outlay money is growing at a slower rate than enrollment in Florida’s public schools. The difference between total enrollment (FEFP in the chart) and needed construction per student (COFTE in the chart) has widened over the past decade.

Growth may not be evenly spread, which means some schools have seen their enrollment shrink, while others may be running out of room. But the chart illustrates a potential for savings, if districts are able to plan for the whole system – not just the students in the schools they run.

In that sense, plans should be holistic, taking all of parents’ options into account. If a school sees its building emptied because students are moving elsewhere, it should consider offering space to charters, or other small, educator-run enterprises that might offer students something different. In fast-growing districts, charters might help districts absorb growth efficiently.

The Palm Beach budget presentation cited above also references new mandates placed on the district in the past 15 years, from state class-size rules to a requirement that schools be built to double as hurricane shelters. Perhaps districts could benefit from greater flexibility in how they meet these requirements. It should be possible to build a system that respects the growing demand for different kinds of school options, while remaining financially sound.