Location, location, location.

Even when parents are able to pick which public school their children attend, it still matters a lot — and can limit the ability of low-income children of color to access high-performing schools.

That’s the takeaway from a new study of school choice in Denver, a city widely hailed as a model for expanded public school choice.

The last sentence of the study, published in the latest edition of the journal Sociology of Education, drives home the key point: “In addition to being able to choose schools, parents need viable options from which to choose.”

Authors Patrick Denice, of Washington University in St Louis, and Bethany Gross, of the University of Washington, find even in Denver — a city with one of the most robust and equitable school choice systems in the country — low-income children of color are less likely to have access to those viable options.

Denver Public Schools have an open-enrollment system for public schools, and the district has seen a proliferation of charter schools, magnet schools and other special programs.

It also has a central application system for all the public schools under its purview, including charters. This makes it easier for parents to select from the full set of options in their city. As a result, unlike in many districts, where privileged students may be more likely to take advantage of school choice, Denver has “relative parity” among socio-economic and racial groups, the researchers write.

During the 2012 and 2013 application periods covered in the study, Black and Hispanic parents were almost as likely as their white counterparts to submit choice applications, and within racial groups, those who qualified for federal lunch assistance were about as likely to apply as those who did not.

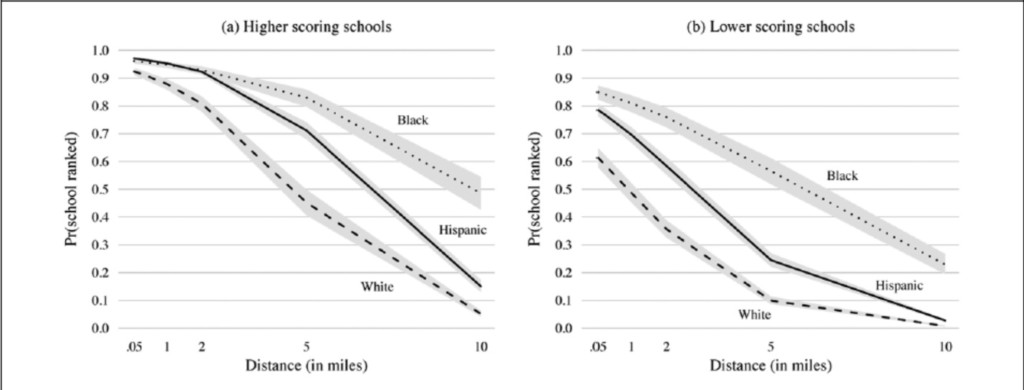

But even though participation in the choice system was relatively equitable, access to high-performing schools was not. White parents generally applied to schools with higher student achievement ratings than their black or Hispanic counterparts. The researchers found this might be a product of geography.

All three racial and ethnic groups tended to favor higher-performing schools. Black families were willing to travel farther, on average, than other groups to get to their preferred schools. And Hispanic families seemed to value academic performance more heavily when they ranked potential school choices.

But high-performing schools tended to be concentrated in areas of the city that placed them out of reach for black and Hispanic parents. As a result, they often had to “sacrifice performance for proximity.”

“Despite the intended use of school choice policies to break the link between students’ residence and school, students remain largely separated from one another along racial lines, and nonwhite students remain trapped in lower-performing schools,” the researchers write.

And waiting lists likely aren’t what’s causing the problem. Even under a “best-case scenario” where every school had room to give every student their top choice in a school choice application, black and Hispanic students would still be more heavily concentrated in low-performing schools, and white parents would remain more concentrated in higher-performing ones.

Black and Hispanic families, in other words, “are choosing from a different set of schools than are white families,” the researchers write.

This leads them to conclude “the availability of choice on its own is not a sufficient condition for equity.” There need to be other improvements in the public education system that give disadvantaged children access to quality options close to where they live.