A recent report from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools raised a question: Has charter school growth stalled?

The alliance’s data shows 329 charter schools opened this fall around the country, while 211 closed. That means the number of charter schools increased by just 118. California and Texas accounted for more than half the national increase.

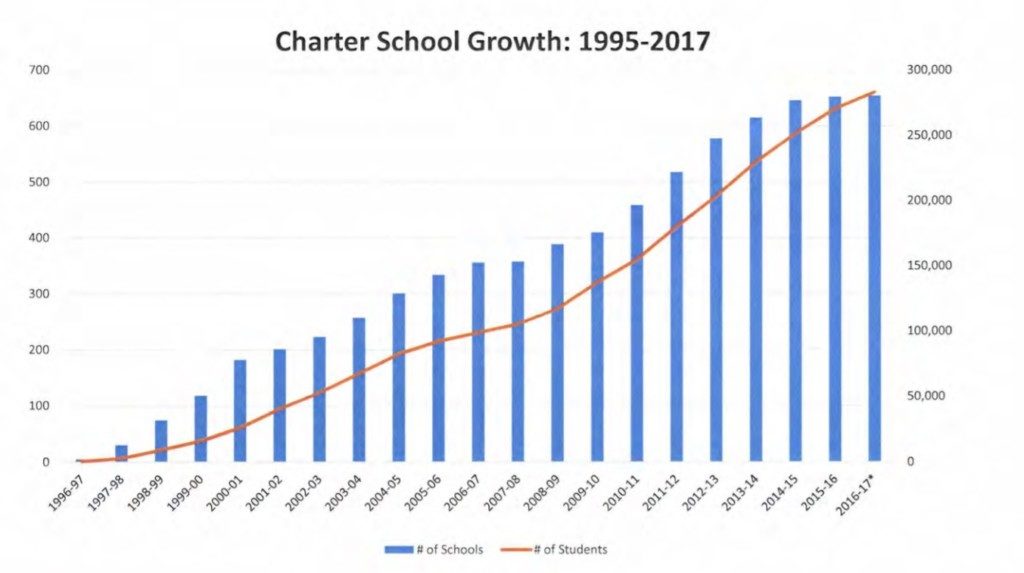

Just a few years ago, the compounding growth of charter schools was so great, it was possible to imagine an all-charter public school system. But political and economic forces may be conspiring to slow that trend. The number of students enrolled in charter schools continues to rise, and has now surpassed 3 million nationally. But if fewer new charter schools are opening, those numbers, too, could soon level off.

Robin Lake of the Center on Reinventing Public Education unpacks some of the factors that may drive the numbers. Authorizers may be getting more stringent, giving fewer charters the green light to open. Highly qualified teachers may be harder to come by, and so may school buildings — or funding to pay for them.

A closer look at Florida may shed some light on the national trend.

Since 2014, the number of charter schools in the state has been stuck just above 650. That’s despite the fact that dozens of new schools open each year.

This fall, 26 new charter schools opened. But they largely replaced 23 charters that closed during the 2015-16 school year. The previous year, 38 new charter schools opened, replacing 37 that had closed. (The national alliance count has a slightly different count, but its numbers tell the same story.)

And yet, this graph, which Adam Miller of the Florida Department of Education recently presented to the House K-12 Innovation Subcommittee, shows the number of students enrolled in charter schools continues to rise.

Lake notes that if a stagnating number of schools enrolls a growing number of students, existing schools may simply be filling out their grade levels. That’s likely true. Many high-profile national charter organizations, like KIPP in Jacksonville, add grade levels gradually, increasing enrollment by 100-200 students per year. It’s also possible that the many of the charters that close are small schools that fail to attract many students, while the new ones that replace them are larger and more successful.

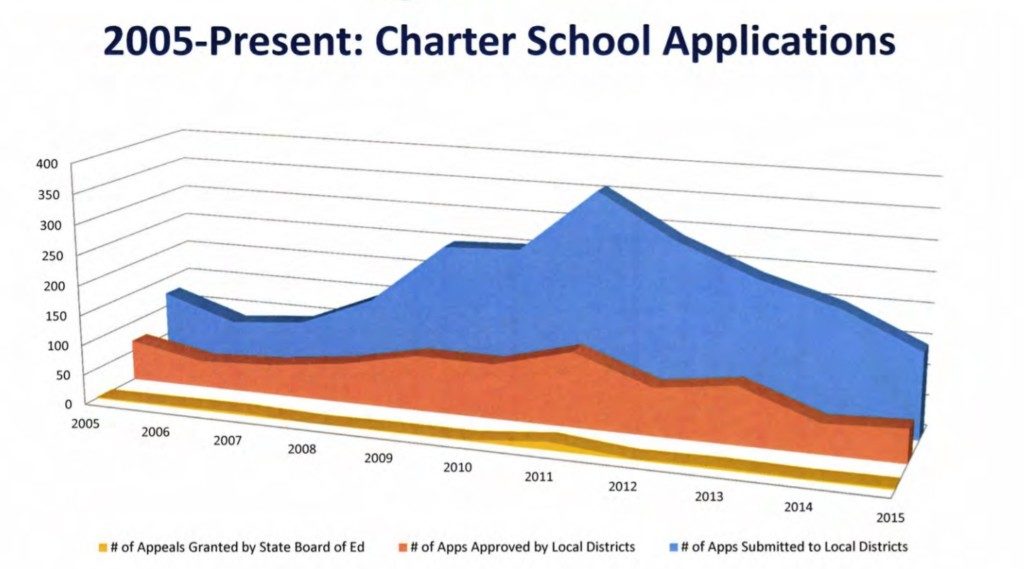

Still, nationally and in Florida, charter growth is stagnating for other reasons. Another graph from Miller’s slide deck shows there are fewer charter organizations applying to open new schools in the first place.

That should put a spotlight on two other potential culprits Lake identifies: The supply of qualified teachers, and access to buildings. Those are two key issues cited by high-profile charter school organizations that are mulling expansion plans in this state.

The stars may be aligning for expanded facilities funding in the state Legislature, though it’s not yet clear how, exactly, it will happen. And several key state lawmakers are interested in opening up the teacher certification system, on the one hand, and raising salaries in the profession, on the other.

If issues like teacher supply and facilities funding are holding back charter school growth plans, that would suggest they could make common cause with traditional public schools, which are dealing with the same problems in Florida and around the country.

If charters can find ways to work with school districts on those issues, they might be able to overcome another barrier to future growth: Authorizer politics, which, in Florida, means school board politics.