“… the modern world is organized in relation to the most obvious and urgent of all questions, not so much to answer it wrongly as to prevent it being answered at all.”

– G.K. Chesterton

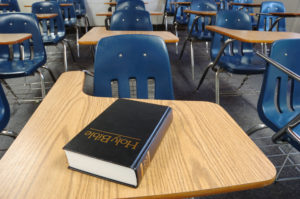

It would have come as no surprise to GKC that the “most obvious and urgent” of human issues – our eternal destiny – is undiscussable in the classrooms of the American public school. For any child’s insistent inquiry about God or no God – heaven and all that – the scripted reply must be “ask your mother.” Thus, it is that – for seven hours a day, 180 days a year for 13 years – the aspirations that can lawfully be pictured for the schoolchild will be variations of “find yourself,” “follow your stars,” “set yourself a high goal,” etc.

Love thy neighbor is, of course, allowed and common in the classroom; the problem is that any pitch for it must be stripped of the transcendental. Thus, a polite justification for brotherly love becomes that “it will make you happy.” Charity itself is made the occasion of self-lore.

Indeed, in the atmosphere of “follow your own star,” the love of one’s neighbor carries the educator’s message that “good deeds” just might catch the eye of potential contributors to one’s own comfort and career – first mom and dad, later your supervisor. The concept of goodness as the pure assent to moral duty – apart from any positive consequence for the actor – is seldom encountered in the public school. The justification for loving thy neighbor gets reduced to utilitarian tips and “moral” inducements like the following ambiguity from Michael Shermer’s new “Heavens on Earth”:

“We create our own purpose, and we do this by fulfilling our nature, by living in accord with our essence, by being true to ourselves.”

Does our law, then, disallow the school’s recognition, for the student, of unselfish justifications for acts useful to another? I suppose that the public-school teacher could safely deliver some less self-centered version of natural law or the universal ethic of Immanuel Kant; both systems are admirable, but, for me, a bit dense and remote, and mean the same for most seniors in high school – maybe college. Here, too, it is only fair to concede that virtually all the public-school teachers I have known well (in and out of my family) themselves have beamed a love that is anything but self-seeking. If only they could, with their students, consider just where such pure charity might originate and where it takes us!

The constitutional jurisprudence that stripped our public school curriculum of transcendence began its reign in the mid-20th Century. With its exclusion of the virtue “faith” from the classroom as its focus instead upon “hope” (transmogrified as a vision of self-satisfaction) it has contributed in turn to the corruption of “love” – historically understood as a spirit of sacrifice and generosity in our social and political relations. School has, for so many children, become an agent simply for maximizing, now and in mature life, one’s physical comfort and self-esteem. This is bad enough for the children of well-off families who have chosen the public school of some comfy suburb; these parents, if they wish, can realistically hope, outside of school, to find effective provenance of a more profound interpretation of our human dignity. And the very fact that these parents have freely chosen, and can well abandon, any school makes their answers to moral questions convincing to the child; yes, indeed, go ask your mother – she knows!

By contrast, the low-income parent who is captive to the public system has, for the child’s mind, already lost the intellectual and moral authority, granted her by nature. With the child’s world crying “be somebody” – and herself unaccomplished and lacking in authority – the parent seems an implausible source of wisdom, and, however loving, no model to emulate.

In the last 20 years it has become clear that federal constitutional law will allow any state to empower parents to depart the public sector in order to discover to the child something more than “success” as the public teacher is permitted to describe it. (The change came in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 2002.) Sadly, however, the constitutions of over half the states contain other barriers to a government’s helping any family to secure the school choice it prefers. These “Blaine Amendments” can be changed only by popular initiative, reinterpretation, or constitutional rebuke by the state’s own courts, or by the U.S. Supreme Court. Such change will take time. How many children of the poor will, in the meantime, get intellectually and morally shorted is unpredictable.

Help may be on its way from the Academy. Berkeley law Professor Stephen Sugarman, in a recent article, has offered the Supreme Court various arguments for scuttling these historic state obstacles to offering religion and in those new and expanding schools of parental choice – the “charters.” As Sugarman observes, though tagged “public,” these institutions operate in a free market, most indeed without a teachers union. Their customer families are as free to abandon one charter for another as to switch from scotch to bourbon. Thus, such chosen institutions must be responsive to the concerns of parents whom the school either satisfies as their best option or goes out of business. In short, they are more private than public in their basic character and thus more than plausibly entitled to offer a picture of the human person far richer than “follow your stars.” Of course, their day of recognition as essentially private remains unpredictable; meanwhile the moral menu of the “public” sector will continue to leave the student unchallenged by any objective much often than popularity, self, and power.

When the liberation of the poor parent does at last arrive, the traditional public school will – properly – remain truly secular and available to parental choice. This will hold true on the condition that, whatever the form or subsidy, every family can afford the full range of participating private school choices including religious charters, but also purely secular and even anti-religious atheist schools.

America has too long cheated the poor family of the tone and substance of education that is so cherished by the rest of us in raising our families. Given the recent Janus decision and the prospect of a Supreme Court majority representing a more traditional version of the parental role, the poor family may yet find itself “free at last.”