Editor’s note: This February marks the 43rd anniversary of Black History Month. redefinED is taking this opportunity to revisit some pieces from our archives appropriate for this annual celebration. The article below originally appeared in redefinED in December 2015.

Credit James Forman Jr. with the best account yet of the center-left roots of the school choice movement. Credit his stint as a public defender for being the spark.

Forman, now a Yale law professor, said the district “alternative” schools serving his juvenile clients in Washington D.C. 20 years ago were giving them the least and worst when they needed the most and best. He began exploring options like charter schools, only to be told by some folks that school choice couldn’t be trusted because of its segregationist past.

Forman, now a Yale law professor, said the district “alternative” schools serving his juvenile clients in Washington D.C. 20 years ago were giving them the least and worst when they needed the most and best. He began exploring options like charter schools, only to be told by some folks that school choice couldn’t be trusted because of its segregationist past.

Forman knew about the “segregation academies” some white communities formed to evade Brown v. Board of Education. But he knew that wasn’t the whole story. Among other reasons, he was the son of James Forman, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the group whose courageous members became known as the “shock troops” of the civil rights movement.

Wait, he thought, recalling stories his parents told him about Mississippi Freedom Schools. Wasn’t that school choice?

“It seemed impossible to me to think that over all of those years, African-Americans had never organized themselves to try to create better (educational) opportunities outside what the state was providing them,” Forman told redefinED in the podcast interview below. “So that was my idea. My thesis was there had to be an alternative history, there had to be a history of African Americans who were not relying on the government and were trying to organize themselves to create schools to educate their children.”

The result of Forman’s research is “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First.”

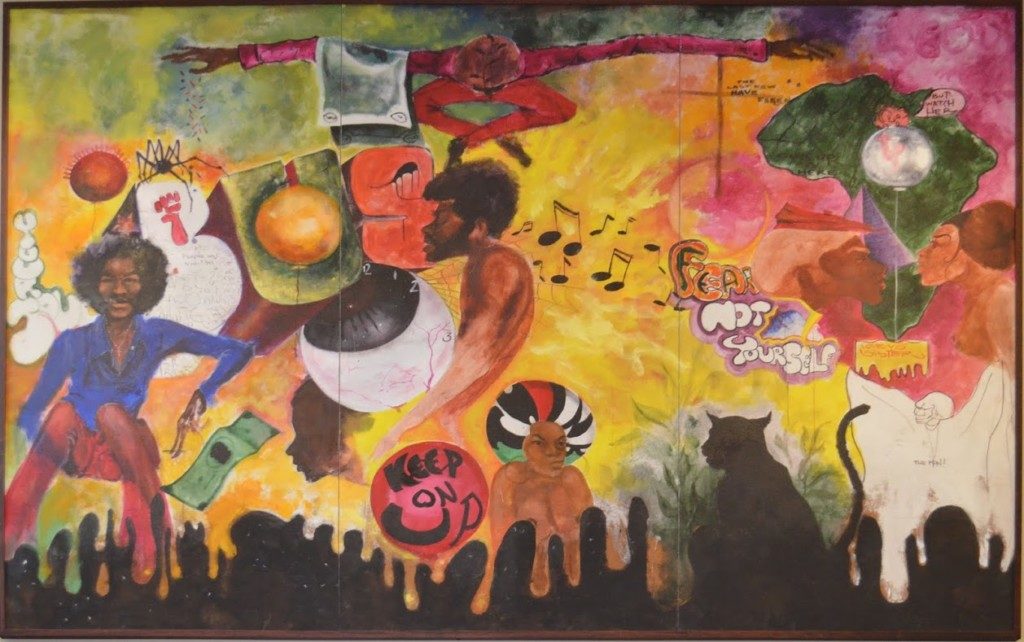

The 2005 paper traces the progressive movement for educational freedom from Reconstruction, to the civil rights movement, to the “free schools” and “community control” movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. A century before many activists were using the term “school choice,” it notes, black churches were making it happen. Decades before conservative Gov. Jeb Bush was pushing America’s first statewide voucher program, liberal intellectuals were promoting the notion in The New York Times Magazine.

A decade later, “The Secret History of School Choice” remains a must-read for anyone who wants a fuller, richer picture of choice’s beginnings. But Forman, who co-founded a charter school named for Maya Angelou, hopes progressives in particular see the light.

They ignore the history of school choice, and their role in shaping it, at their own peril, he said. Believing, wrongly, that it’s right-wing can result in it becoming just that. If progressives aren’t at the table, he suggested, they can’t bring their values to bear in shaping policy. In his view, it’d be good if they did.

Forman, for example, believes per-pupil amounts for many voucher and tax credit scholarship programs are too low for the low-income students they’re intended to help, reflecting conservative positions that education funding as a whole is bloated. (Other left-leaning choice supporters have raised concerns that modern voucher programs are too cheap.) Equity concerns surface in other ways, with few publicly supported, private school choice programs employing the sliding scales for family income and scholarship value that liberal voucher supporters in the ‘60s and ‘70s thought crucial.

“Our understanding of the history influences the direction that the issue goes,” Forman said. “If people who have an equality orientation and a civil rights orientation see themselves as on the outside of the movement for school choice, then the only people who are going to be left are people who have different motivations. … So the question is going to be, who owns the movement? Who directs the movement? Who is dominant? Whose educational vision leads the way?”

Forman said perceptions about choice will change as more and more low-income and minority parents embrace it. But the narrative won’t tack back to fully mesh with the reality of the movement’s diverse roots, he said, unless other things change too. One obvious hurdle, he said, is how the movement’s leadership ranks are “almost lily white.”

“Every time I go to a (school choice) conference, I am appalled by how invisible almost the folks of color can be at the top level of leadership,” Forman said. “That’s a problem.”