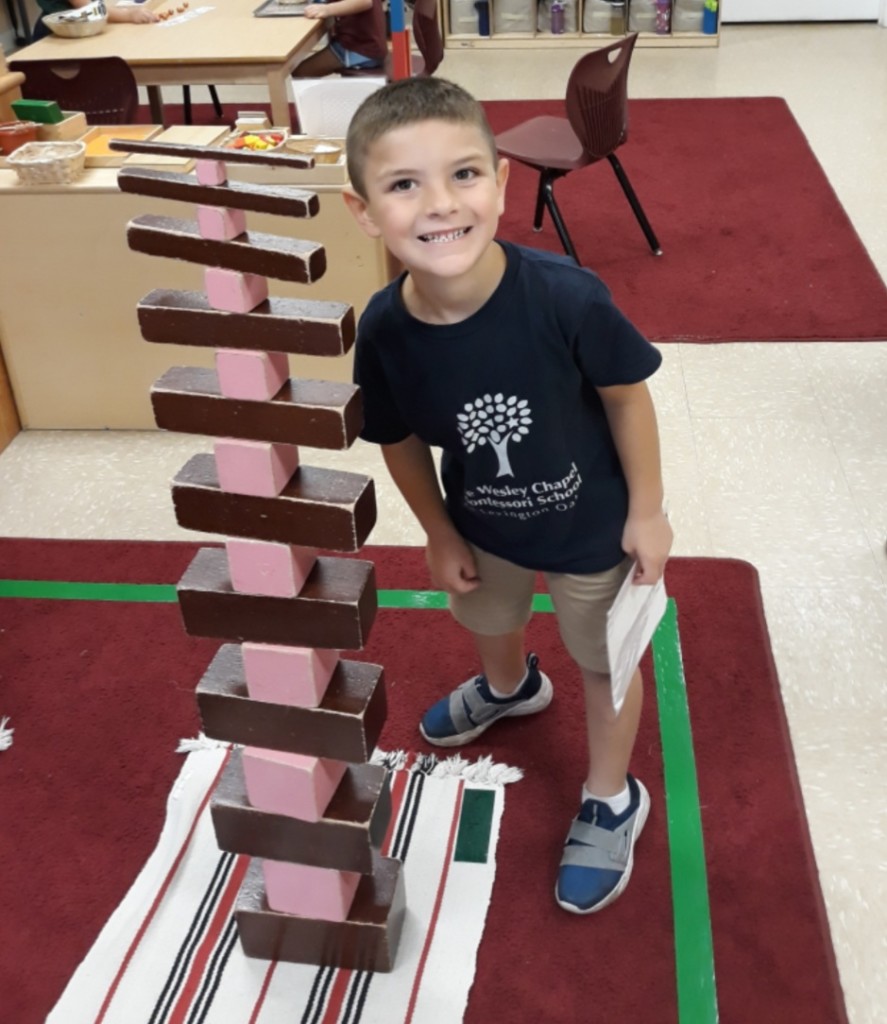

Brody Cholnik, 5, struggled with virtual prekindergarten but is showing promise as a kindergartner at the Wesley Chapel Montessori School at Lexington Oaks. His mother, Nicole Cholnik, chose to send him to a private school so she and her husband, rather than the public school district, will be able to make the decision to have Brody repeat kindergarten if necessary.

Even after eight months of pre-kindergarten, Brody Cholnik struggled to learn his ABCs. Regular sessions with a private tutor and supplemental lessons at home helped, but Brody’s mother suspected something beyond her control was in play.

Her 4-year-old’s birthday wouldn’t come until several months after many of his classmates already had turned 5. She worried that it put him at a disadvantage. On top of that, Brody’s pre-kindergarten was held in the day care he attended as a toddler and he was accustomed to it being a setting for play.

“It was hard for him to transition from a play atmosphere to a school atmosphere,” Nicole Cholnik said.

Then last spring, just when Brody began showing progress, COVID-19 hit. The tutoring center closed. His pre-kindergarten class made a hasty retreat to Zoom. And Brody, who was still two months away from blowing out the candles on his 5-year-old birthday cake, fell further behind, prompting Cholnik to wonder: What if my son needs to repeat kindergarten?

When school officials told her that decision rested with the principal, not with her and her husband, Cholnik took matters into her own hands. She transferred Brody to a private Montessori school, a move that allows her to maintain control over her son’s fate when he turns 6 and is required by state law to be enrolled in school.

"If we decide as parents that he's not ready for kindergarten, then next year when he goes to (his zoned school) he can do kindergarten again," said Cholnik, who lives in a suburb just north of Tampa. "Or, if we feel he's prepared enough and ready for first grade, we can give them the certificate of completion and put him into first grade."

A controversial but growing trend

A parent’s choice to delay kindergarten, commonly called “academic redshirting,” became a hot topic in academic journals in the early 2000s. Author, journalist and public speaker Malcolm Gladwell put redshirting on the public radar in 2008 with his bestselling book “Outliers,” championing the practice and arguing that the practice made a difference in a student’s long-term success.

Over the years, redshirting has been argued about in countless parenting blogs, journals and news stories, with critics saying it can harm children later in school.

There are many pieces in play. Research indicates the phenomenon tends to happen more frequently in white families, and more often with boys than girls. Because redshirting can require families to pay for an extra year of day care or kindergarten fees, it’s more common among those whose incomes fall in the middle or upper brackets, prompting equity concerns.

One argument supporters make in favor of redshirting is that when families hold children back a year, the child then likely will be the oldest and possibly most mature in his or her class, and therefore possibly more able to successfully compete in academics and sports.

Redshirting has taken on a new prominence in the COVID-19 environment as schools nationwide began reporting falling enrollments, especially in the kindergarten ranks, with the start of the 2020-21 academic year. According to an NPR survey of 100 school districts, the average kindergarten enrollment drop was 16%.

The survey attributed the decline partially to the emergency pivot to online learning in the spring. The negative experiences left some families dissatisfied and in search of other options, especially in districts that started the new school year 100% online. One parent of a 5-year-old boy in Texas told NPR she had concerns regardless of whether the school opened online or in-person because an in-person experience was going to be “weirdly socially distanced and masked.”

Though the parent chose not to delay kindergarten for her son, she did send him to a private school where masks were optional and class sizes were smaller.

High stakes for empty seats

Some Florida school districts experienced enrollment declines as well, especially in the early grades. An October student count in Palm Beach County showed enrollment for pre-kindergarten through 12th grade in district schools at 187,776, the lowest level since 2016.

Kindergarten saw the biggest hit, with a decrease of 1,416 students, or 12%, compared with the previous fall. The figures prompted district chief financial officer Mike Burke to speculate that parents were delaying their children’s entry into school. It also caused district leaders to begin worrying how the enrollment decline would affect education funding for the district.

Though local property taxes contribute to education funding, districts depend on per-student funding based on the number of students occupying seats. At the start of the 2020-21 school year, districts were able to shield their funding by striking a deal with the state that allowed them to maintain pre-pandemic funding levels in exchange for reopening brick-and-mortar campuses. That deal expires at the end of first semester, leaving administrators bracing for draconian funding cuts in the spring.

‘A tough conversation’

For the Cholniks and other families who are sitting it out this year, learning is still happening, although it may be unique ways, such as reading books together at home and playing with Nerf guns, or enrolling in a private kindergarten that gives the parents the option of having their child take a second shot at kindergarten next year.

Brody has made progress at his private school, but Cholnik predicts he will end up having to repeat kindergarten. In the meantime, she has scheduled testing to see if he has a learning disability. If tests uncover an issue that has “a simple fix,” there’s a chance Brody could move on to first grade next year.

But Cholnik would rather have Brody repeat kindergarten than enter first grade behind his peers, and eventually have to repeat fourth grade if he fails the standardized test the state requires for public school promotion.

“That would be a tough conversation to have at that age,” she said. “That’s why we’re taking this route now."