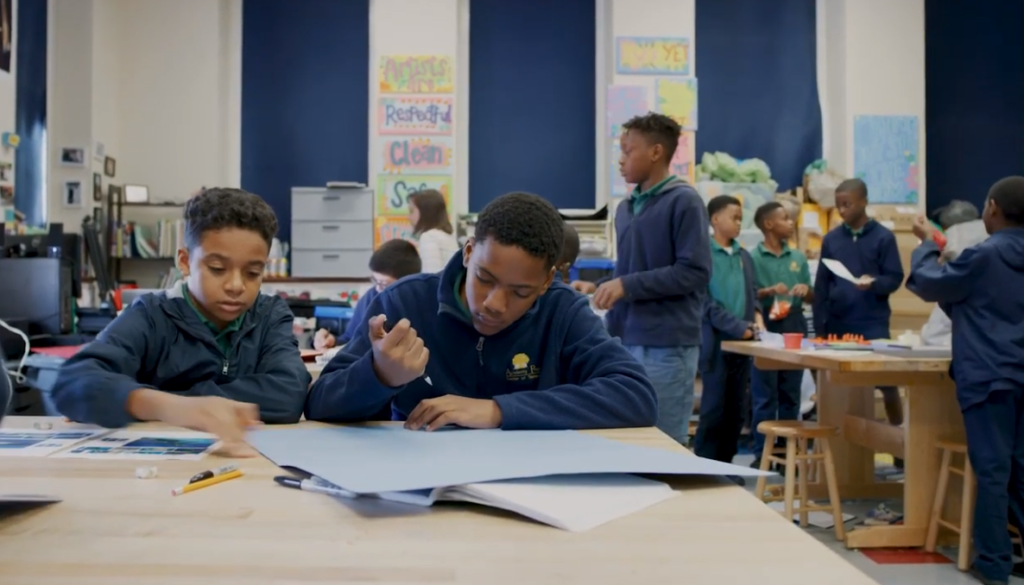

Students at all three locations of Academy Prep -- Tampa, St. Petersburg and Lakeland -- routinely matriculate to top high schools and go on to attend top colleges. All Academy Prep students attend on state scholarships.

There is no evidence that students who use Florida school choice scholarships return to public schools worse off academically.

There is no evidence that students who use Florida school choice scholarships return to public schools worse off academically.

But that doesn’t stop critics of education choice from repeating variations on that claim.

The Florida League of Women Voters is the latest to air this “damaged goods” myth. In a Feb. 21 newspaper op-ed criticizing Senate Bill 48, which would convert Florida’s school choice scholarships into education savings accounts, two of its officials wrote:

“Stories abound of children who return to their neighborhood public school after a private school closes, only to find they are far behind academically.”

But for the qualifier “after a private school closes,” the Florida League of Women Voters op-ed echoes a charge that choice opponents have been levelling for years (for example, here and here.)

We can’t say with certainty whether “stories abound.” But data to support such claims certainly does not.

The authoritative take on this issue comes from respected education researcher David Figlio, dean of the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern. For years, Figlio was tasked by the state of Florida with annually analyzing the standardized test scores of students using the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the biggest choice scholarship program in the nation. (The scholarship is administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

In his 2011-12 report, Figlio addressed the academic performance of scholarship students who return to public schools. He wrote:

FTC participants who return to the public sector performed, after their first year back in the public schools, in the same ballpark but perhaps slightly better on the FCAT than they had before they left the Florida public schools. The most careful reading of this evidence indicates that participation in the FTC program appears to have neither advantaged nor disadvantaged the program participants who ultimately return to the public sector.

Figlio also wrote:

These pieces of evidence strongly point to an explanation that the poor apparent FCAT performance of FTC program returnees is actually a result of the fact that the returning students are generally particularly struggling students.

Subsequent analyses led to the same conclusion.

The best available evidence doesn’t point to shortcomings with choice scholarships. If anything, it underscores the need for even more options for the most fragile students.

Other evidence also turns the League of Women Voters claim on its head.

Thirteen years’ worth of test score analyses offer remarkably consistent findings about Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students. No. 1, they were typically the lowest-performing students in their prior public schools. And No. 2, they’re now, as a whole, making a year’s worth of progress in a year’s worth of time.

A 2019 Urban Institute study found even more encouraging results: The same students are up to 43 percent more likely than their public school peers to enroll in four-year colleges, and up to 20 percent more likely to earn bachelor’s degrees.

These outcomes don’t suggest damaged goods.

They suggest more students living up to their potential.