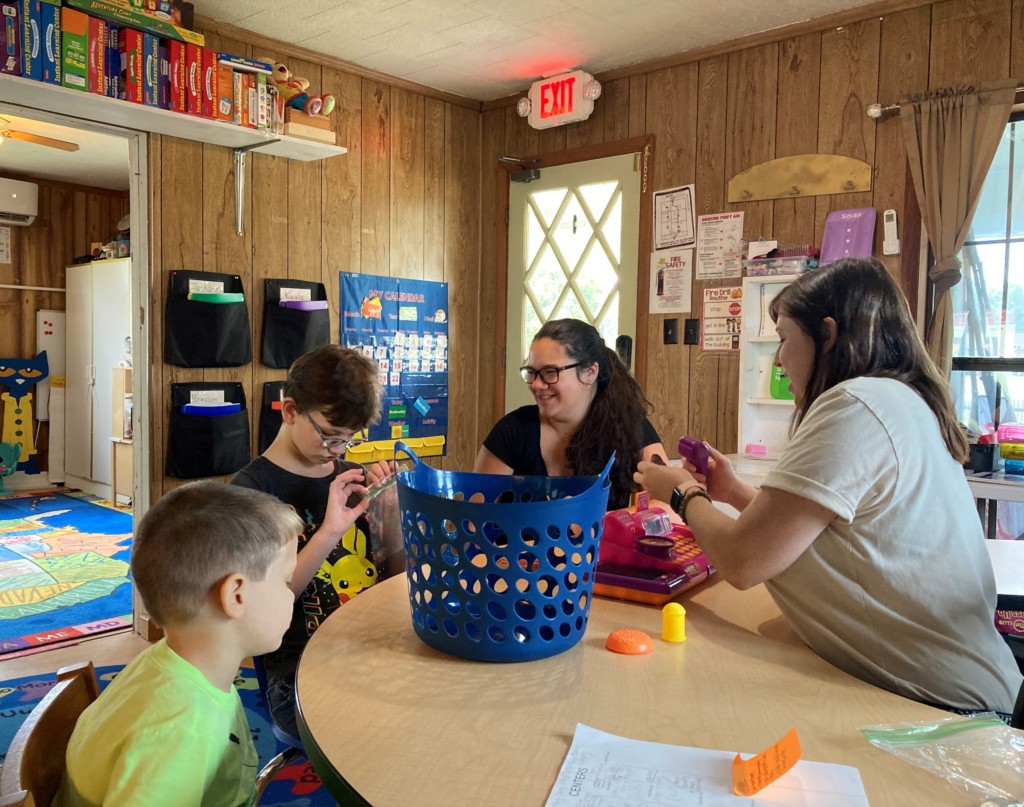

Gold Star Private Academy in Bristol, Florida, adheres to an educational philosophy that presumes student competence, valuing family as part of its team and focusing on service, compassion, and connection. The school serves students with special needs, all of whom use state-funded school choice scholarships.

Editor's note: In keeping with our year-end tradition, the team at reimaginED reviewed our work over the past 12 months to find stories and commentaries that represent our best content of 2022. This post from Step Up For Students' Ron Matus is the third in our series.

BRISTOL, Fla. – Liberty County is half covered by a national forest. It’s wall-to-wall pine trees. Its only incorporated city has 996 people, and they’re outnumbered by bears.

BRISTOL, Fla. – Liberty County is half covered by a national forest. It’s wall-to-wall pine trees. Its only incorporated city has 996 people, and they’re outnumbered by bears.

Even here, though, school choice has taken root.

Four years ago, a tight-knit family of educators who worked in local public schools for generations opened Gold Star Private Academy.

Gold Star serves students with special needs. All of them use state-funded school choice scholarships. And their parents describe it with terms like “life changing” and “total miracle” and “the greatest school on the face of the Earth.”

Donna Franklin enrolled her son Brayden, who is 15 and has Down syndrome, after four other schools in three counties. At one of them, staff recommended corporal punishment be incorporated into Brayden’s behavioral plan. At another, an aide dragged him down a hallway.

Liberty County in the Florida Panhandle is the Sunshine State’s most rural county, with 9.5 people per square mile. If it were a state, Liberty would be No. 47 in population density, between North Dakota (11.3 people per square mile) and Montana (7.5 people per square mile).

Franklin gave home schooling a shot, but Brayden, she said, needed the social immersion of a full school experience.

So nothing worked – until Gold Star.

“If Gold Star had been here 12 years ago, he’d have had an entirely different childhood experience,” said Franklin, a registered nurse and hospice administrator. “I can’t express enough the need for choice. And the need for schools like this to be everywhere.”

Gold Star Private Academy is another good example of what happens when public education funding follows the child.

Even in a town with one stop light, supply grows to meet demand.

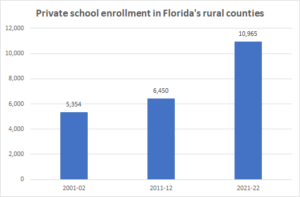

In the last 20 years, the number of private school students in Florida’s 30 rural counties has doubled, from 5,354 to 10,965, according to state data. About 70 percent of them use school choice scholarships.

Meanwhile, the number of private schools in those counties has grown from 69 to 120.

“If you can do this in Bristol,” said another Gold Star parent, Marlene McAllister, “you can do this anywhere.”

***

Gold Star Private Academy was co-founded in 2018 by (from left to right) Johnette Wahlquist, Sally Sims, Jordan Wahlquist, Janna Hill and Kalynn Richardson. They decided to start the school after hearing a friend, a former school district administrator, describe how she started her own private school in another rural county. “We’re educators,” Hill said. “We thought we may as well do it ourselves.”

Gold Star is a family affair.

Sisters Janna Hill (a former district science teacher) and Johnette Wahlquist (a former district nurse) co-founded the school with Wahlquist’s daughter Kalynn Richardson (also a former district nurse); Wahlquist’s daughter-in-law Jordan Wahlquist (a former district speech pathologist); and Jordan’s mother, Sally Sims (another former district science teacher).

Altogether, the family has more than 200 years of combined experience working in local public schools, including three members who were former superintendents.

At one point, the sisters were opponents of school choice.

At one point, Hill led the local teachers union.

But times change.

Gold Star Private Academy was born after a decade of frustration, after family members watched their children and grandchildren struggle in the same schools they worked in.

“I didn’t understand what the parents were going through until I experienced it myself,” Johnette Wahlquist said. “Now I could see the inadequacies and the holes in the system.”

Johnette’s son Christopher, 19, is diagnosed with MPS1, a rare genetic condition that left him with auditory and visual impairments and a tracheostomy to breathe.

Her granddaughter Grey, 10, is diagnosed with Phelan-McDermid Syndrome, another rare genetic condition that can cause speech and other developmental delays.

Her grandson Blaine, 11, is on the autism spectrum.

In ways big and small, traditional schools didn’t work for them.

Christopher didn’t get the alternative communication and hearing impaired services he needed. Grey often did not have the fully trained, full-time aide she was required to have. In Blaine’s case, some staff members suggested his mom find another school.

So she did – by helping to create one.

In Florida, this is becoming a common story. A growing number of private schools in Florida – including some in rural counties like this one and this one – are being started by former public school educators.

In the spring of 2018, the Hill and Wahlquist family was at a get-together with friends that included a former district administrator. The administrator had moved to another rural county and, with the help of school choice scholarships, set up a school for students with special needs. (Those scholarships are administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

After another rough year, nobody in the family wanted Grey and Blaine back in the same schools. So when the friend described how she opened her own school, the family members looked at each other and said, “Why can’t we?”

They poured over a chart showing scholarship funding amounts for student with special needs. On average, those scholarships are worth about $10,000 each.

The math added up.

The family found a building they could rent at a reasonable rate. A few months later, they opened Gold Star Private Academy, named in honor of an uncle who died in World War II.

That first year, the school had six students.

Last year, it had 17 – and a waiting list.

This fall, Gold Star is planning to move into another building with three times the space.

The family isn’t sure how big the school should get. They’d like to also serve general education students. The bigger building will give them options.

***

Traditional schools didn’t work for Brayson McAllister, so his mom, Marlene McAllister, enrolled him in Gold Star. Brayson, 7, is autistic and blind and has a brain development condition called septo-optic dysplasia. Brayson can learn and play complicated pieces on the piano after just a couple of listens, but with subjects like math, he needs more time and repetition to stay on track. Enrolling Brayson in Gold Star, Marlene McAllister said, was “the best move I ever made.”

In the meantime, multiple families are grateful Gold Star gave them an option.

Jade Hug said her daughter, Keira, who is 6 years old and on the autism spectrum, couldn’t keep pace with the general education students she was mainstreamed with.

Her family considered moving to Tallahassee, an hour away, so they could enroll Keira in another school that serves special needs students. But it wasn’t a given the other school would be better and the Hugs would have to leave friends and family behind.

Gold Star turned out to be a “game changer,” said Hug, a stay-a-home mom and former nurse – not only because Keira got a school that worked for her, but because the family could stay rooted in their community. “That was one of the best things about it,” she said.

Hug also credited Gold Star staff with constantly updating her about resources and strategies that might help Keira – and communicating in down-to-earth terms that didn’t overwhelm her.

The world of special needs can be “intimidating,” Hug said. “The people at Gold Star say, “We’ll help you. We’ll teach you.’ “

Janna and Johnette said most of the children in their family continue to attend public schools and do well in them. The school and the district, they said, have a good relationship.

One Gold Star student who struggled in public school returned after getting back on track.

Melissa Peddie enrolled her now 16-year-old, Jessie, in Gold Star after growing weary of battling for help with his anxiety disorder. She tried homeschooling but said she didn’t have the time or skill to do it well.

At Gold Star, she said, she could finally breathe again.

“They understood his needs. They were so tender and caring,” said Peddie, a paramedic. “He came home from school happy. He was a different child.”

Now Gold Star wasn’t a perfect fit. Jessie missed students his age. He wanted to play guitar in the school band. He wanted to be in JROTC.

So after two years at Gold Star, Jessie enrolled in the district high school.

This time, with his confidence restored, Jessie’s grades improved. Over the summer, he got an internship with the U.S. Forest Service.

Had Gold Star not been there, Peddie said, Jessie would have dropped out.

“I wish the world had a Ms. Janna and a Ms. Johnette to fight for their child. They were my guardian angels,” she said.

“Because of them, we’re going to make it through.”