A district makes a painful decision to close school plagued by persistent low performance and low enrollment.

Fortunately, the closest school is a high-performing, highly sought-after affluent urban enclave. Unfortunately, most students affected by the closure won’t have access to that school. Instead, they will wind up in nearby schools with lower achievement levels and more space to fill.

This is the crux of the story of Tampa’s Just Elementary, as rendered by Tim DeRoche in The 74.

DeRoche, the founder of a new advocacy organization devoted to equalizing access to public schools, argues convincingly that assigning students to schools based on where their parents can afford to live is anathema to the ideal articulated 69 years ago by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education that public schools must be available to all on equal terms.

School districts in cities like New Orleans have made nearly all public schools open to all students, and set rules assuring students affected by school closures receive priority access to other public schools. The disruption of closures can be painful, and research shows the quality of the schools where affected students wind up can be crucial to their academic trajectories.

The problem in Hillsborough County is that many of the well-regarded public schools are full, and the parents who paid exorbitantly through the housing market for the privilege of a guaranteed spot are unlikely to yield their exclusive access.

The solution, DeRoche argues, is to break the link between geography and school assignment. He concludes: “School access needn’t be a zero-sum game governed by bitter political fights over maps.”

Embracing public school open enrollment and eliminating geographic assignment are essential, but they may not be enough to end the zero-sum game on their own. In school systems that have created large numbers of public-school options that break the link between the housing market and school access, the wealthy and well-connected seek other ways to rig the game. A few years ago, former D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Antwan Wilson illustrated this reality when he attempted to bypass a public school’s admissions lottery and wound up losing his job.

To create a positive-sum game, we need to confront an under-appreciated enemy of progress in education: Scarcity.

Some public universities are working to break scarcity’s stranglehold. Over the past 10 years, my alma mater, the University of Florida, has grown its enrollment by about 20 percent, adding roughly 10,000 students. Half of that growth has occurred at its traditional brick-and-mortar campus. The other half has come through a new online program. And the university is experimenting with other models that would allow it to serve more students, while creating flexible opportunities that fit their lives. Its new Innovation Academy serves nearly 1,000 students who attend classes during the spring and summer, but free up their fall semester to pursue passion projects.

These efforts are in their early days, but the same principle should apply in public education: Make opportunities abundant. Highly sought-after institutions should look for ways to serve as many students as possible. They can do this by making flexible use of technology, time, and space.

What could this look like in a school district like Hillsborough County, where some highly sought-after schools are over-enrolled, but others struggle to fill their available space with students? Here are three ideas:

Use the flexibility of online learning to serve more students. Gorrie Elementary, the highly sought-after school with costly surrounding real estate prices, may not be able to follow every aspect of UF’s playbook and reach more students through online learning. Full-time virtual school just isn’t a good fit for many elementary-aged students. But experimenting with models that combine online learning with in-person support could allow over-enrolled schools for older kids, like Plant High School, to serve more students without needing to build more classrooms.

Share space in existing public schools. In school districts like Denver and Mesa, Arizona, districts have invited microschools to share space in their buildings.

Small learning environments gain access to district facilities. Their students gain opportunities to interact with larger peer groups without sacrificing the intimacy and individual attention that drew them to microschools in the first place.

Districts, meanwhile, can fill space in underused buildings, offer more innovative programs to their students, and attract families (and revenue) that might otherwise leave the district for private schools or homeschooling.

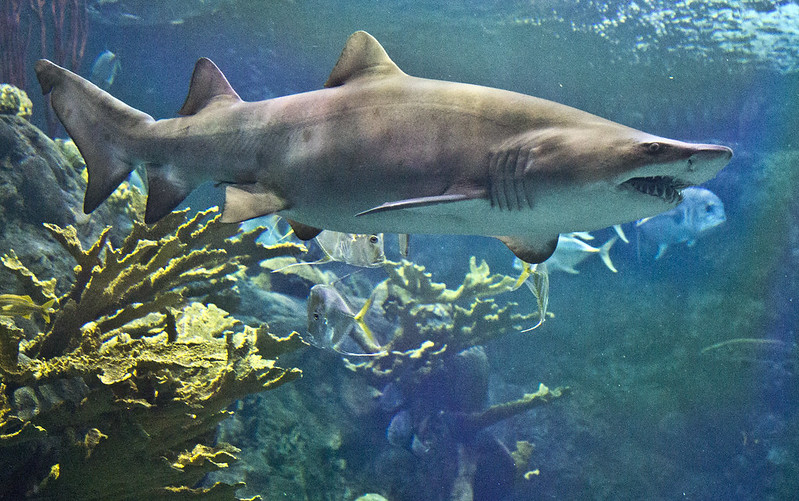

Reimagine where and when students learn. District schools could also draw inspiration from UF’s Innovation Academy, and rethink conventional assumptions about what the school calendar looks like, or where and when learning happens. Florida’s new part-time enrollment law allows students to enroll in district programs that don’t use the full day or year. Other learning opportunities could fill the remaining space on the calendar. A school near downtown Tampa could treat the city as an extended classroom, partnering with the Florida Aquarium, Glazer Children’s Museum, and other nearby institutions to provide learning experiences to students who also spend time in traditional classrooms. A field trip to the museum or the aquarium could be the highlight of a student’s year. Why limit it to a single day?

This combination of opening more spots in sought-after schools to more students and filling under-enrolled schools with more diverse learning options has the potential to make high-quality learning opportunities more abundant. It may be the only way to detoxify the zero-sum politics that typically surround school assignment.

Districts that commit to creating abundant opportunities will likely bump into state laws that hold them back. New legislation passed this year kicks off a process to identify these barriers so state policymakers can address them, and the Florida Department of Education is taking suggestions.

In the meantime, as my colleague Ron Matus points out, there are private schools in the vicinity of the closed Just Elementary run by highly qualified Black educators that, thanks to the expansion of state scholarship programs, are able to serve students of all incomes.

School districts in Florida have a unique advantage compared to their counterparts in other states: Enrollment, statewide and in most districts, is growing, in both public and private schools. Eventually, declining birth rates and shifting migration patterns may catch up with our state, too. There is no time like the present to create abundant opportunities for everyone.

Image credit: “A visit to the Florida Aquarium” by LimpingFrog Productions is licensed under CC BY 2.0.