Rumors of the death of public education have been greatly exaggerated.

Rumors of the death of public education have been greatly exaggerated.

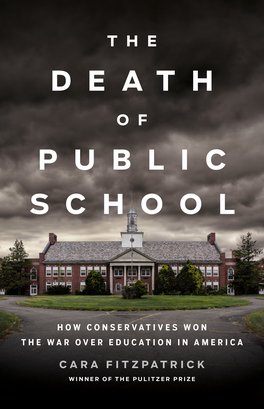

Any reader who gets past the cover of The Death of Public School: How Conservatives Won the War Over Education in America is likely to agree. The book never articulates the claim implied by its title.

It does, however, provide a thorough and insightful account of more than a half-century of fights in courtrooms and state legislatures to redraw the boundaries of public education to encompass more alternatives to district-run neighborhood schools.

Cara Fitzpatrick, an editor at the education news site Chalkbeat who won a Pulitzer Prize for an investigation of institutional failure in Florida’s Pinellas County school district, introduces her narrative with statements from Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who in the past two years have signed into law the nation’s most ambitious expansions of educational choice.

Both governors declared public education includes a broad range of learning options funded and accessed by the public, from schools operated by districts to a la carte educational services purchased by parents using education savings accounts.

Fitzpatrick’s history begins in the 1950s, when three separate strands of thought converged on similar ideas. Economist Milton Friedman argued for unleashing market forces by allocating public education funding to individual students. On religious freedom grounds, the Catholic cleric Virgil Blum argued public subsidies should help ensure all families had access to parochial schools. Across the South, segregationist lawmakers sought to evade Brown v. Board of Education by creating publicly funded private alternatives to public schools.

While the first two strands held the most enduring influence on the modern school choice movement, the third triggered years of legal battles. The NAACP’s attorneys played Wac-a-Mole with attempts by Southern officials to evade integration orders. Both the civil rights organization and the Black parents it represented committed themselves to ensuring equal access to uniform public school systems—a stance that may help explain the NAACP’s present-day skepticism toward charter schools and vouchers.

Meanwhile, Blum’s efforts to secure public support for religious education suffered a crippling blow in Committee for Public Education v. Nyquist, in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a New York program offering tuition grants, tax credits and other subsidies.

And, beginning in the 1960s, a growing chorus on the left advocated new approaches to public education. These including Harvard sociologist Christopher Jencks and Kenneth Clark, a psychologist who helped secure the victory for desegregation in Brown. Fitzpatrick quotes Clark’s 1968 essay that argued “public education need not be identified with the present system of organization of public schools. Public education can be more broadly and pragmatically defined in terms of that form of organization and functioning of an educational system which is in the public interest.”

In the mid-’70s, these ideas were tested in Alum Rock, a North California school district that launched a short-lived experiment providing families with a diverse range of educational options that, to today’s readers, resembled something like an array of publicly funded microschools. In Fitzpatrick’s telling, Alum Rock’s foray proved burdensome to administer, and families, while they valued additional options, were loath to unleash unfettered forces of creative destruction upon their local schools.

Voucher efforts gained momentum across the country, and in 1990 secured a major breakthrough in Milwaukee, thanks to a left-right alliance between Black community leaders frustrated with the state of public schools and Republicans inspired by Friedman. Voices on the left sought new forms of compromise, and in the process, furthered efforts to redefine public education. Minnesota’s Democratic Gov. Rudy Pepich backed an expansion of public-school open enrollment. Teachers union head Albert Shanker warned the growing political momentum behind vouchers “poses the question of whether there will be public education in America.” Years later, he would respond with a widely publicized proposal to support charter schools.

Meanwhile, a decades-long legal effort sought to turn the tide in courtrooms around the country. Led by Clint Bolick, an Arizona Supreme Court justice who started his career as a scrappy libertarian public interest attorney with a knack for publicity and an eye for sympathetic narratives, its eventual victory is embodied in William Rehnquist’s progression from author of a dissent in the 1973’s 6-3 Nyquist ruling to author of 2002’s 5-4 decision upholding Cleveland’s voucher program in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris.

In Zelman, defenders of the voucher program successfully persuaded Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the critical swing vote, that public funding for private school tuition stood alongside charter schools and other reform efforts in a broader effort to secure the secular goal of improved education opportunities for the city’s children. In other words, the vouchers program was part of a new definition of public education.

After the climactic legal battle in Zelman, Fitzpatrick’s narrative fast-forwards toward the present, touching on the oft-panned Bush v. Holmes ruling in which the state Supreme Court temporarily stymied Florida’s school voucher expansion and noting the creation of the nation’s first education savings accounts. The narrative stops during the Trump Administration, just before the widespread school closures and the flourishing of new education options that redefined the boundaries of public education, and schooling, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.

Fitzpatrick’s treatment of these more recent events is confined to her introduction, where she quotes the conservative culture warrior Chris Rufo arguing that “to get universal school choice you really need to operate from a premise of universal public school distrust.” Public polling and this year’s legislative events suggest otherwise. Public schools and expansive choice policies like universal education savings accounts both enjoy majority support, and while trust in public schools is declining (alongside most other institutions in American life), universal choice is growing quickly at a time when distrust is far from universal.

Fitzpatrick laments that, in a polarized political climate, “it feels as if there’s no middle ground to be found in education.” But her own narrative points to where middle ground can be found. It’s sketched out in the Zelman decision, and advocated, in varying ways, by such diverse figures as Ron DeSantis, Doug Ducey, Kenneth Clark, and Christopher Jencks: Public education must continue to flourish, and at the same time, it must be redefined to encompass a wider range of learning options chosen by parents.

Translating that middle ground into public policy will require thoughtful debates about how funding is allocated, how progress is measured, and how educators are regulated. This book doesn’t advance a point of view on those big debates. But it offers valuable historical perspective on how to advance them.

Other views

Jay Greene, writing in Ed Next, and Naomi Schaefer Riley, writing in The Wall Street Journal, both argue Fitzpatrick’s characterization of individuals and events suggest the author has a rooting interest against the school choice movement.

Publishers Weekly praises the book, tidily connecting the emergence of vouchers to fights over segregation in a far more simplistic fashion than Fitzpatrick does in her nuanced narrative, and incoherently contending that charter schools, which are public, “became a far more successful method of diverting resources from public education.”

A starred Booklist review lauds the effort and concludes: “In Fitzpatrick’s capable hands, a sequel would certainly be much appreciated.” The events of 2020-present would certainly provide plenty of material.