Who benefits from remote work?

Research says that on average, remote workers are less productive from employers’ perspectives. But they may be more productive from a different perspective: They spend more time caring for family members.

The appeal of remote work is all too often glossed over as a matter of “quality of life” or “work-life balance.” Those are, of course, important. But that framing also ignores the uncompensated caregiving that Vigil and millions of others provide for America’s young, sick, elderly, and disabled. Their efforts are not just a quality-of-life issue; they’re an enormously important and overlooked part of our economy. For a lot of caregivers, telecommuting allows them to manage a workload that is, if anything, way too big. Remote work, then, isn’t just a question of work-life balance; it’s a question of work-work balance. The traditional conception of “productivity” doesn’t account for this.

Why it matters: Parents who work from home and spend flexible time caring for family members may clamor for schools that allow them to get more directly involved in co-producing their children’s education.

What if less is actually more when it comes to parent-school communication?

In a national survey that was published in 2013, only four out of ten K-12 families reported receiving a phone call about their child in the preceding school year. But, when the coronavirus pandemic prompted a switch to remote schooling, parents of younger kids were often in near-constant, direct contact with teachers—to log attendance, submit classwork, and get help with assignments. After full-time, in-person learning resumed, the steady trickle of one-to-one calls and texts that I continued to receive from school—alongside the cascade of school-wide, grade-wide, and class-wide announcements on ClassDojo—seemed somewhat vestigial of COVID times.

There’s a sad paradox in the fact that the pandemic increased the amount of contact between many teachers and parents at the same time that it spiked the tensions between them. During remote learning, teachers could see inside their students’ homes, and parents could peek inside classrooms and at library shelves; neither group necessarily liked what they saw. Schools could make no COVID-era decision without worrying or angering many families, whether it concerned masking and testing mandates, closures, or hybrid-learning schedules. Some teachers believed that parents wanted to force them back into classrooms under unsafe conditions; some parents believed that wary teachers were malingering. (These ostensibly opposed groups heavily overlapped: most teachers are parents.)

Why it matters: If co-production is becoming the norm, parents and schools will need to find new, more effective ways to communicate and build trust.

Who are tests for?

More states are shifting from administering one single test at the end of the school year to multiple tests throughout the year. This challenges existing assumptions about school accountability.

The old accountability model was built on outdated assumptions that the primary audience for test scores should be policymakers, not teachers, students, or parents, said Mike Fulton, lead facilitator of the Success-Ready Student Network, the group in Missouri leading the work to change testing.

“That is a model centered on the notion if we just weigh the schools and report out on how they’re doing, improvement will occur,” Fulton said. “But the assessment actually has nothing to do with informing continuous improvement in real time, making adjustments in real time, informing instruction, informing school design on how time and structures … are used to support learning.”

Why it matters: Parents and teachers are souring on top-down school accountability but may see value in bottom-up approaches that give them a clear look at how their students are doing, and the power to choose different options.

Need to know

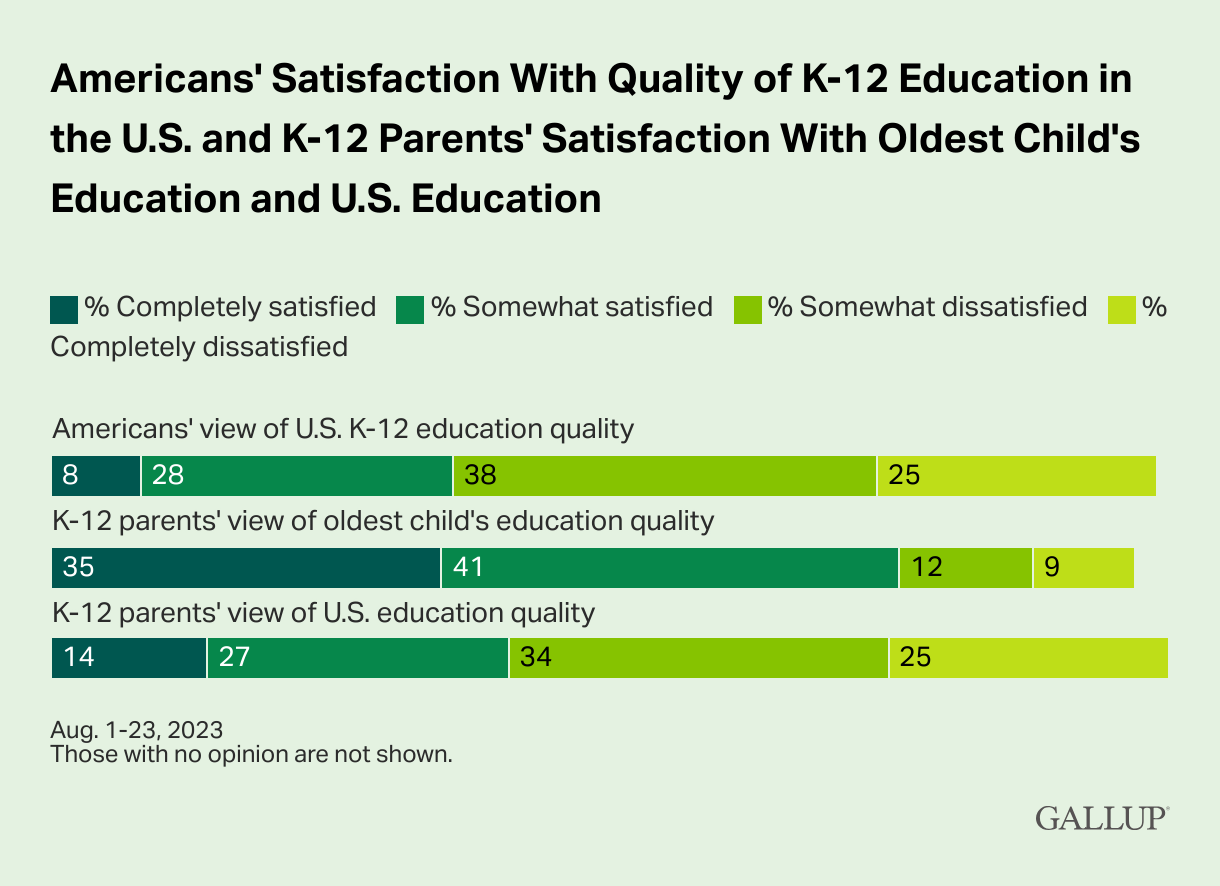

Parents are far more happy with schools with which they have direct personal experience than with education in general.

A new study finds redrawing school attendance boundaries based on parents’ preferences would reduce segregation and travel times.

Schools’ staffing decisions rest on the outdated assumption that educated women have few professional career options.