Francis Ford Coppola shot a scene for Apocalypse Now set in a plantation owned by die-hard French imperialists holding out in Vietnam. Set in 1968 during the height of the Vietnam War, the film follows Capt. Benjamin Willard’s journey up a river to eliminate a rogue American colonel. The French plantation scene has an eerie feel, as if Willard had, in journeying up the river, had somehow traveled back in time to the 1950s. Willard’s French hosts argue amongst themselves over old defeats and bygone disputes as a prelude to bitterly proclaiming their desperation to hold on to their anachronistic estate.

So as is often the case with my long-suffering but deeply appreciated readers, you are probably wondering what this has to do with education policy. I’m getting to that; do please stick with me. Michael Petrilli and Devon Nir recently published a piece called “The ‘à la carte education’ accountability conundrum” a few weeks ago. The piece addresses the complexities around education savings accounts and concludes with the following paragraph:

The idea of à la carte education, supercharged by education savings accounts, has captured the imagination of school choice advocates far and wide. No doubt families (especially those already homeschooling) welcome the “free money,” and elected officials are happy to reap the electoral rewards. But as a sustainable strategy to promote choice and innovation, publicly funded “unbundled learning” is hard to justify. Especially if we’re talking about large ESAs, directing tens of thousands of dollars a year to families with two or three children, taxpayers will sooner or later demand to know what they are getting for the investment. The answer will inevitably be “we don’t know.” That’s just not good enough.

The French plantation scene came to mind when I read this. The strange journey through time does not take us back to the era of European imperialism, but rather back to the era of naive enthusiasm for K-12 managerialism- circa 2000-2009. The reform strategies of that era did not prove sustainable and ended about as well as Dien Bien Phu did for the French. Policies aimed at expanding access to à la carte education meaningfully vary across states and will be adjusted over time. Choice policies, in fact, address the central flaw of the 2000-2009 era strategies by developing active constituencies. Are we, as the piece suggests in danger of losing them?

International exams have for decades demonstrated that American students on average fall increasingly behind their European and Asian peers as they age through the system. These same exams show exceptionally large achievement gaps in favor of high-income students over low-income students. We have failed to unpack exactly why we see such huge achievement advantages in favor of advantaged students, but as I’ll demonstrate below private enrichment spending seems like a prime suspect.

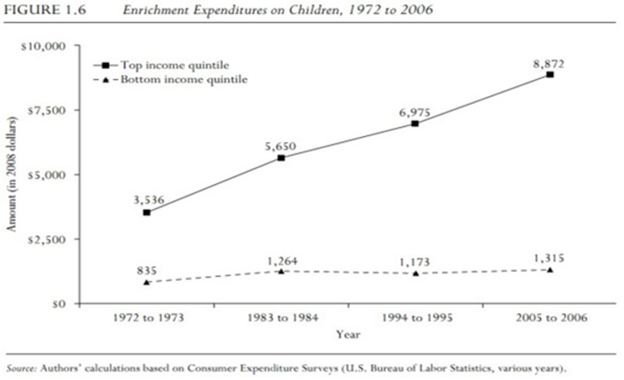

Now of course many American schools show relatively high levels of academic proficiency. How they achieved those high levels however is neither simple nor obvious. Circling back to the topic of à la carte education leads us to the rather unavoidable conclusion that we don’t really know why schools with relatively high levels of proficiency have those high scores. Kids in public schools do multi-vendor education as well. In fact, high-income families have been engaging in more and more à la carte education over time:

How would American schools brimming with students engaged in always-increasing levels of enrichment look in the absence of all those tutors? We don’t know. That’s indeed not good enough, but many decades into an accountability era of education we can’t answer even such a basic question. Perhaps we should give scholars studying the much younger choice programs a bit of grace, as we remain utterly clueless on the impact of à la carte education on public schools.

One thing we do know: the demand for à la carte education has been growing strongly. Upper-income American families displaying the same sort of maniacal fervor for enrichment that Col. Bill Kilgore had for surfing. Enrichment spending likely has the intended effect: providing an advantage for the students engaged in it.

KUMON or FIGHT!

How are the legions of enrichment programs and services held accountable? The normal way: through voluntary association and exchange. This mostly happens through informal networks and reputation. Platforms collecting reviews on schools and professors debuted decades ago but have yet to be perfected in the à la carte education space. People are working on it.

In the meantime, both the traditional type of à la carte education (exemplified by the chart above) and the sort exercised in ESA programs and personal use tax credits have proceeded fine without the guidance of managerialism. Vietnam managed to carry on without the French bossing them around, and the mistakes they made were their own mistakes. Families likewise have mastered à la carte education without the need for anyone’s permission. ESAs and personal use tax credits simply expand the universe of participants.

We might want to pause to consider that perhaps the sort of spontaneous arrangements around these activities might work fairly well before rushing to “improve” them. Legislative trends indicate that programs expanding access to à la carte education are easily justified on both prudential and moral grounds. Parents using ESAs are entirely free to hire and fire à la carte vendors and service providers, whereas they have no ability to select or fire public school personnel. The vendors are directly accountable to families.

Unlike the French character urging Capt. Willard to crush the Vietnamese, we should learn from mistakes and not feel overly eager to repeat them. As à la carte education expands across the nation, we will make mistakes. That’s both unavoidable and normal. We should, however, at least try to limit ourselves to new mistakes rather than repeating old ones.