This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

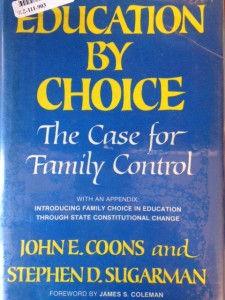

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

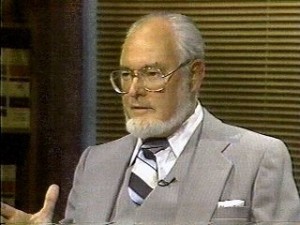

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution.

To put it in today’s terms, the Coons-Sugarman plan would, in one fell swoop, create more educational options for the parents of 4.5 million California students than Florida, the most choice-friendly of states, has done in the past 20 years. Even more than the new, near-universal education savings accounts in Nevada, it would take a wrecking ball to the old order and install a new one overnight.

Would is key.

These were scholars. This was a plan in a book.

Then, suddenly, it wasn’t.

In the fall of 1978, according to Coons, U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan, a respected, three-term California Democrat and former public school teacher, embraced it. What had been a template for consideration by somebody, someday, would soon be a living, breathing plan for action: the “California Initiative for Family Choice.”

Coons, now 86, said he and Ryan decided to shoot for the June 1980 ballot. They would need 553,790 signatures. They had until Jan. 4, 1980 to do it.

He and Sugarman dove headfirst into electioneering, a sphere they knew nothing about, and immediately sent shock waves rumbling across California’s education landscape.

As the first Sunday dawned in 1979, thousands of people strolled out to their drive-ways in palmy Southern California. Awaiting them were these words, beneath a front-page headline in the Los Angeles Times:

The idea is called school vouchers. But this particular form turned out to be too radical even for the 1960s, and it died aborning. Although they were solidly against the concept, professional education groups didn’t really consider vouchers a serious threat then.

Now, however, the voucher idea is alive again, but not just as a theory or a pilot experiment.

A statewide initiative is being proposed to make California the first state to establish an entire system of voucher schools, including public, private nonsectarian and religious.

The story continued:

California’s educational establishment is alarmed as perhaps never before. Top leaders realize that the success of Proposition 13 – and the fact it has not produced the disaster that was predicted by opponents – may mean the public is willing to take a chance on another ‘radical’ governmental reform.

Translation?

This could happen.

Cue “Le Freak.”

***

Private school vouchers for grades K-12 were indeed radical in the 1970s – and obscure. The first major, modern voucher program wouldn’t be created until 1990, in Milwaukee. The first major, modern statewide program wouldn’t be created until 1999, in Florida. The first major, modern program to be used by more than a small percentage of students – well, there still isn’t one. Not in America.

Milton Friedman sprang the idea of vouchers (or refined it, if you’re inclined to give Adam Smith, Thomas Paine and others a share of credit) in 1955, but two decades later it still wasn’t much of a blip on the ed reform radar. A policy cousin, tuition tax credits, was getting attention from both political parties. Some influential academics saw incredible potential.

On the flip side, voters in a handful of states were rejecting ballot initiatives that hinted at public funding for private schools. In 1978, Michigan voters rejected a proposal for vouchers. But, to most people in California and anywhere else in America, the idea might as well have been dropped from the mothership in “Close Encounters.”

To be clear, Coons and Sugarman weren’t just talking vouchers.

They wanted vouchers, and charter schools, and a vehicle that allowed parents to tailor their kids’ educations in a way that foreshadowed the education savings accounts that are being passed in state legislatures today. They also wanted a raft of regulations they deemed necessary to protect the interests of low-income families.

They wanted to change it all. And all at once.

Maybe they weren’t the only ones.

Cue “The Boys Are Back in Town.”

***

Congressman Leo Ryan liked what he heard over dinner at his cousin’s. According to Coons, he subsequently called the law professor and asked to talk about his school choice ideas in more detail.

They met again, this time at a nice restaurant in San Francisco.

Coons was there. Ryan was there. And, according to Coons, so were two of Ryan’s top aides: G.W. “Joe” Holsinger, his veteran chief of staff, and 28-year-old Jackie Speier.

Coons said he gave them the detailed ballot proposal from the Coons-Sugarman book, “Education by Choice.” He said they were excited, and confident it could pass. He said there was at least one other meeting with Ryan and his staffers to go over the details.

Along the way, Coons said, Ryan agreed to be the face of the ballot initiative. Just as importantly, he agreed to raise money for the crucial effort to gather signatures.

An epic thought crossed Coons’s mind.

The sea has parted.

Cue “Pump It Up.”

The Berkeley professors had found a powerful ally.

Congressman Ryan was popular and fearless, a liberal with a maverick streak, a square peg with a common touch. It’s a safe bet he was the only member of Congress with a master’s in Elizabethan literature. And importantly for a ballot initiative that sought to make school choice the law of the land, he had been a teacher in California public schools.

Ryan also had a knack for making headlines.

Before election to Congress in 1972, he served nine years in the state assembly, where he became famous for exploring the nitty gritty behind the news. One newspaper called it “investigative politics.”

After riots in Los Angeles, Ryan worked as a substitute teacher in the Watts neighborhood. A few years later, he went undercover to experience death row at Folsom Prison. As a congressman, he visited Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, at one point laying down on the ice between a hunter and a seal pup.

As fate would have it, Ryan was also a voucher guy.

Years later, Jackie Speier, his former aide, would point to his support for school choice as a prime example of his political independence. Ryan “seemed unlike other politicians,” Speier said. “He was provocative; he didn’t mince words or beat round the bush; he told you what was on his mind whether you wanted to hear it or not; and he took pride in not being able to be pigeonholed into any one ideology.”

Ryan may have been willing to buck his party on vouchers. But it’s also true it wasn’t as odd for Democrats in the 1970s to back public support for private schools.

In 1977, Democratic U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan introduced a bill for tuition tax credits that drew 50 co-sponsors – 26 of them Republicans and 24 of them Democrats. At that time, the previous three Democratic candidates for president, Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McGovern and Jimmy Carter, had backed similar proposals on the campaign trail.

According to Coons, Ryan was all in on the voucher initiative. The congressman was headed to South America, but after their last meeting, Coons said Ryan told him this:

“You guys are going to polish this up as best you can, and we’ll get ready to announce it and start pushing it through the process just as soon as I get back.”

***

As word spread, panic mushroomed.

The Los Angeles Times predicted the voucher initiative would be “the biggest and most bitter fight over schools in many years.” State Superintendent Wilson Riles predicted “chaos.” The executive secretary of the powerful California Teachers Association, Ralph Flynn, said his group would defeat the proposal “whatever the cost.”

Even Al Shanker, the legendary leader of the American Federation of Teachers, weighed in, saying the California proposal could produce “the fight of the century.”

By early 1979, Riles was urgently contacting supporters, mobilizing for a statewide campaign.

If this thing gets on the ballot, he told the San Jose Mercury News, “who knows what might happen.”

Game on.

***

Coons and Sugarman didn’t dream up their plan on a whim. They had been refining it for a decade.

The motivation was simple – to give parents, particularly poor parents, real power to determine the best education for their children. But the details were complex. Unless the new system was well designed and regulated, they believed, low-income children would continue to be denied a fair shake.

The professors envisioned three types of K-12 schools under a new banner of public education, all to be called “common schools.” There’d be:

The professors envisioned three types of K-12 schools under a new banner of public education, all to be called “common schools.” There’d be:

Parents could choose whatever common school they wanted, with public funding for family choice schools coming in the form of “educational certificates,” i.e. vouchers. But Coons and Sugarman veered from conservative and libertarian models in key ways.

Access: Under their plan, independent public schools and family choice private schools would be required to set enrollment limits at each grade level. Then they’d be required to accept every student who applied up to those limits, beyond those previously enrolled and given priority. If the number of applicants exceeded the number of open seats, there’d be a lottery.

Funding: The average scholarship amount would be 90 percent of total per-pupil spending for traditional public school students, but the Legislature could adjust the amount based on special needs, cost-of-living and other factors. It would also create a system of “supplementary scholarships” that allowed parents to apply for additional funding based on a sliding-scale for income. In other words, low-income parents could receive more state money, to make it easier for them to access higher-tuition schools.

Regulations: All three types of schools would be required to provide transportation with conditions set by law. None could discriminate based on race, religion or gender. The Legislature would establish uniform standards for discipline, create programs to fund capital costs and provide a public database with information about each school. It would also offer grants for parents to hire education advisors.

As for cost, the California Initiative for Family Choice proposed capping total public spending on elementary and secondary education at 1979-80 levels, with subsequent increases only for inflation and enrollment growth. It would nix property taxes as a source of school funding.

The professors also wanted to ensure the state couldn’t stall.

Within five years, the Legislature would have to devote enough resources to the establishment of independent public schools and private family choice schools that 30 percent of the state’s K-12 students could enroll in them.

By way of comparison: About 10 percent of Florida students are in private schools in 2015, even with the nation’s biggest tax credit scholarship program (established in 2001) and one of its biggest K-12 voucher programs (established in 1999). After 20 years in existence, Florida’s charter school sector, also among the nation’s biggest, accounts for 8 percent of K-12 enrollment.

Too much, too fast?

Coons had no qualms. He thought of the suffering America’s system of public education was inflicting on low-income families, particularly black families. If we can end it, he concluded, we should end it.

With Ryan, they had a chance.

***

The establishment wasn't about to wilt.

The executive secretary of the state teachers union called the Coons-Sugarman plan “social dynamite” and said it would make public schools the dumping grounds for the poor. He said it would create a “permanently institutionalized drone class.”

The teachers union president in San Diego said vouchers would appeal to “all the racist antibusing fans” and open a Pandora’s box of extremism.

“We can have People’s Temple schools and the public will support them. We can have Nazi schools and Hare Krishna schools and devil’s arts and observing-the-wall schools,” he said. “And we can have a nation of little individual philosophies running around, and Hare Krishna and People’s Temple schools all going around zapping each other.”

Later in the year, at a legislative hearing on vouchers, another teachers union leader went even further, saying the school choice plan was “a cruel and vicious attempt at not only educational apartheid but also educational genocide.”

Opponents knew timing favored the insurgents.

This was just months after 62.6 percent of voters flipped off the government with Prop 13, the tax revolt that reverberated across America. This was years before today’s dominant narrative about school choice – right-wing plot to privatize public schools – had been set in stone. And these were liberals – Left Coast, Berkeley liberals, at least by perception – leading the vanguard.

In October 1978, a statewide poll showed 59 percent favoring vouchers.

From Chula Vista to Crescent City, school boards and teachers unions couldn’t believe what they were seeing: From an unexpected place, the unmistakable surge of a tidal wave.

They weren’t the only ones thinking the worst.

South of San Francisco, an electronics engineer and inventor in Redwood City read about the liberal-led California Initiative for Family Choice and thought: Disaster.

Not because it would kill the public school system. Because it would perpetuate it.

Libertarian Jack Hickey didn't like the Coons-Sugarman school proposal, and crafted a competing proposal for "performance vouchers."

Jack Hickey saw too many regs, too little freedom, too much potential to “contaminate” private schools. He was certain the massive school choice plan engineered by the Berkeley professors would curtail choice, not expand it.

“I looked at that and said, ‘That’s bad, that’s really bad,’ “ Hickey said in an interview.

Hickey wasn’t content to grump. The libertarian activist would eventually run for office 18 times, including for governor, U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives. In this case, he nimbly sketched out a counter-proposal, something he called a “performance voucher.”

Then he and Roger Canfield, a police consultant in nearby San Mateo, began their own sprint to the ballot.

***

At the time of his meeting with Congressman Ryan, Professor Coons was best known as one of the attorneys who changed how public schools are funded in California.

He and Sugarman were key players in a legal effort that began in 1968 with a widely publicized case, Serrano v. Priest. It charged that the way California financed public schools – by relying heavily on local property taxes, resulting in huge disparities between rich and poor districts – violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Over the course of a decade, Serrano led to three California Supreme Court rulings that spurred the state legislature to mitigate funding disparities between districts. It’s also credited with sparking school finance reform in other states, even though a ruling from a similar case in Texas was struck down in a 5-4 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Coons’s embrace of school choice flowed, initially, from the funding inequities he saw. Ultimately, he and Sugarman, his protégé and intellectual partner, came to this conclusion: Giving poor parents more power to choose schools for their children best allowed them to rise above an entrenched education system blatantly rigged against them.

The professors first fleshed out their voucher idea in 1971, in a 118-page treatise for the California Law Journal. In the foreword, another Berkeley professor channeled a view about public schools that wasn’t uncommon for progressive thinkers of the era:

If a set of families enters a state park to go hiking, that group would be shocked indeed to discover that the scenic trails were reserved for its richer members and that only barren and rocky paths were held open for the poor. Nevertheless, our public schools operate in such a discriminatory way.

Not all choice enthusiasts looked primarily through that lens.

***

Like Coons and Sugarman, the libertarians wanted to end the old regime, not modify it.

Hickey and Canfield’s proposal would abolish government-run schools, end compulsory education and stop measuring academic progress merely by number of instructional days (wonks call that “seat time.”) Every parent would be given a voucher of equal value, $2,000 per year. (Per-pupil spending in California at the time was about $3,000 per year.) Through a contract with the state, the parents could spend the money on a school, on a teacher or teachers, on educational materials, or on any number of other things and combinations.

The performance voucher had, in the words of Hickey and Canfield, “divisibility.” In that respect, they, like Coons and Sugarman, foreshadowed today’s latest spin on vouchers – education savings accounts – years before think tanks fleshed them out.

But the performance voucher also had another irregular feature that made it distinct: It couldn’t be redeemed until the student showed progress, as determined by a standardized test.

No progress. No payment.

Like the Berkeley professors, Hickey and Canfield saw their proposal empowering parents and teachers, fostering competition and reducing bureaucracy – but, in their view, in a simpler, more direct way that wouldn’t produce new reams of red tape. They thought their plan would withstand legal challenges on church-state grounds. They also wrote, pointedly, that it was “not designed to redress social ills.”

Feisty and intense, Hickey jumped into the ballot effort with both feet. It wasn’t long before he was putting in a call to a certain Nobel-Prize-winning economics professor.

***

Coons was the yin to Milton Friedman’s yang. His case hinged on morality, not markets.

In his view, a revamped public education system with vastly expanded choice wouldn’t just open the door to better academic outcomes for students. For parents, it would beget responsibility, legitimacy, dignity. Coons reasoned that once poor parents had the power to routinely do what more affluent parents take for granted – to make that most important of decisions, how best to educate their children – other, monumentally good things would follow.

The future anchor of the Voucher Left grew up in Minnesota, the son of a traveling kerosene stove salesman. Before law school, he had worked as a truck driver, served as an officer in the U.S. Army, and played linebacker for the University of Minnesota at Duluth. In college, the same guy who liked to lay the big lick on halfbacks also sang lead in a jazz band.

Education policy came by way of serendipity. As a law professor at Northwestern in 1962, Coons was hired by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights to report on racial segregation in Chicago public schools. The professor it wanted to hire was too busy.

From there, Coons rose to rub shoulders with some of the most iconic figures of the times. In the 1960s, he hosted a radio show in Chicago, where Friedman was a frequent guest, and he discussed the legal implications of boycotts with Martin Luther King Jr. In the early ‘70s, he rode with Daniel Patrick Moynihan, from Urbana to Chicago, in a blizzard; bar stops were frequent. Coons and Sugarman also had enough academic heft to enlist legendary education researcher James Coleman into writing the foreword to two of their books, including 1978’s “Education by Choice.”

For Coons, this wasn’t academic. His easy smile and gentle demeanor belied a militant’s passion. He recoiled at the injustice of education in America every bit as much as other activists were horrified by racism or Vietnam.

In the middle of the ballot effort in 1979, Coons paused to duel with a voucher critic, R. Freeman Butts, in the pages of Phi Delta Kappan. He noted the tragic disparities in public schools between Beverly Hills and Watts, then lowered his shoulder:

And that is what Professor Butts calls public education. It is a play on words, a corruption of our language; for public is the one thing such a system is not. It was and remains a profoundly elitist, exclusive, and undemocratic structure of privilege paid for by taxation – one in which the rich get choice and deductions, and the poor get sent.

Cue “Fortunate Son.”

***

Vouchers weren’t the only thing on Congressman Ryan’s mind.

In the summer of 1977, Jonestown, Guyana had become the new headquarters for the People’s Temple, formerly based in San Francisco. Jim Jones, the temple’s charismatic leader, bought the land in the jungles of South America in 1973, not long after the first negative media reports about his cult surfaced. Four years later, as scrutiny mounted, Jones fled to his new sanctuary, bringing hundreds of temple members with him.

Back in the Bay area, negative stories kept piling up.

In 1977, Ryan heard from a friend, a guy he met when he was a high school teacher. The man’s son had been a member of the People’s Temple, but was found dead, his body mutilated, not long after he talked of leaving. Ryan began investigating. He heard from other constituents worried about family members. They shared stories of abuse. They said people were being held against their will.

Ryan went to the State Department, but officials there were not helpful.

Jim Jones had cultivated friends in high places. He helped George Moscone became mayor of San Francisco. He met several times with Vice President Walter Mondale. At a dinner honoring him in 1976, California Gov. Jerry Brown was among those in attendance. Despite the evidence, political allies continued to defend him. After a damning San Francisco Chronicle story in February 1978, Harvey Milk, the openly gay city supervisor who would be assassinated a few months later, fired a letter to President Carter. Temple defectors, he wrote, were spreading lies about “a man of the highest character.”

Ryan decided to see for himself.

He chaired a congressional subcommittee with jurisdiction over Americans abroad. He asked other Bay area congressmen to go with him. All declined.

Undeterred, Ryan announced on Nov. 1, 1978 that he was going to Jonestown.

On Nov. 14, 1978, he arrived.

The professors wanted Milton Friedman’s blessing. So did the libertarians.

Calling Friedman was the “first and natural thing to do,” Coons recalled in an interview. The two had known each other since the early 1960s, when both lived in Chicago. Coons hosted a radio show; Friedman was a frequent guest.

As luck would have it, Friedman was now based at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, in nearby Palo Alto. He and Coons and their wives occasionally met for dinner.

Initially, Friedman was excited and encouraging about the ballot initiative, Coons said. Then he wasn’t.

The regulations spooked him, Coons said. Friedman never told him directly. But he heard as much from potential donors to the initiative campaign, and it wouldn’t have been surprising. Friedman’s biggest fear about school choice was government intrusion.

According to Coons, donors told him Friedman had been in contact with them and said the plan was wrong-headed. He convinced them to hold off on contributions, and to wait for better school choice proposals down the road.

***

The libertarians had better luck.

Hickey said he sent Friedman a copy of his "performance voucher" proposal, and talked to him by phone. He said Friedman liked it enough to give it a positive review in writing. As proof, he produced a letter from Friedman on Hoover Institution letter head.

Friedman wrote that he liked how the performance voucher would curb government’s role in education, but was bothered by heavy reliance on standardized testing. He concluded, though, that “any one of the three approaches (an unrestricted voucher, your approach, or an appropriately designed tax credit) would be vastly superior to our present system.”

Both David Friedman, Milton Friedman’s son, and Robert Enlow, president of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, said the letter appears to be authentic.

***

For some, two competing choice proposals weren’t enough. In the summer of 1979, petitions began circulating for a third.

The educational tax credits promoted by the libertarian-minded National Taxpayers Union would give California taxpayers a state income tax credit of up to $1,200 per student for educational expenses, including private school tuition. Public school parents could also use the tax credits, for things like field trips and lab fees.

The NTU was allied with the forces that spearheaded Prop 13, and the group’s West Coast director characterized the choice proposal as an extension of the tax revolt. He told a reporter the group came close to supporting Coons-Sugarman, but ultimately decided against it because “it didn’t leave the private schools free from control.”

Jack Dean, a longtime libertarian activist who worked on the NTU effort, said in an interview that the professors’ plan gave libertarians heartburn. “The tuition tax credit was kind of the antidote,” he said.

Milton Friedman praised the NTU proposal too, saying in a letter to Dean, “Its effect would be essentially identical with the kind of unrestricted voucher plan I have been supporting and promoting for decades.”

Dean said his recollection is NTU spawned the proposal, then asked Friedman for support. He said the group didn’t raise much money from major donors, but Friedman’s endorsement helped.

Cue "Ain't No Stopping Us Now."

***

Now the professors were under fire on two fronts. And yet, as summer unfurled, their plan continued to roll.

In August, supporters mailed out 200,000 petitions, prompting these words in the Los Angeles Times:

Public education groups, which are bitterly opposed to the voucher plan and vow to fight its passage, have been watching fearfully for nearly a year as the initiative effort took shape.

Now, the potential threat has become a reality with the official start of the petition campaign.

The consensus is that the voucher plan, called Family Choice in Education, stands an excellent chance of winning voter approval – if the initiative qualifies for the ballot.

The story noted Coons and Sugarman seemed to have overcome initial hurdles.

They had hoped to get a voucher bill introduced in the state legislature in the spring, to generate publicity, but no lawmaker was willing to “face the wrath of education groups, including powerful teacher unions.” They also didn’t have immediate luck finding a campaign consultant, but eventually hired a veteran known for his work for “liberal candidates and causes.”

The consultant had previously worked on the campaign for the state superintendent of public instruction. He boldly told the newspaper his goal was a million signatures, with 800,000 by the end of November.

Cue “Don’t Stop Til You Get Enough.”

***

The coverage missed what was happening behind the scenes:

The liberals were floundering.

As if to underscore the point, The Sacramento Bee reported in September that the education establishment had decided on a new strategy for the initiative: Ignore it.

California’s educational establishment has decided not to launch a full-fledged campaign – for the time being – against the proposed school voucher initiative, a strategy designed to give the controversial measure as little publicity as possible …

Coons and Sugarman had no experience with political campaigns, and it was beginning to show. Lack of money and organization was becoming a major issue. And private schools were getting edgy. They told newspapers the regulations in the plan were too much.

By mid-October, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which should have been a steadfast ally, still hadn’t determined whether it would support the initiative.

The deadline for 553,790 signatures was just 10 weeks away.

More than ever, the campaign was missing the man who had spurred it on and agreed to lead it.

***

Congressman Ryan never returned from Jonestown. He was murdered on Nov. 18, 1978.

Jim Jones’ thugs shot him at the airport. Four others in his entourage were killed; nine were wounded. Later that day, Jones ordered more than 900 temple members to drink cyanide-laced Flavor Aid.

Only two months after his introduction to Ryan, Coons felt the same shock as the rest of the planet, and tremendous sadness for Ryan and his family. At the same time, he knew the ballot initiative had been rocked, too.

Coons and Sugarman did their best to soldier on. For a year after Ryan’s death, their efforts to make their vision of school choice the law of the land in California got serious play.

But the truth is, its odds for success all but died when Ryan did.

***

The Berkeley professors failed to get enough signatures. The two competing efforts also fell short.

Coons called it quits on Christmas Day, 1979.

“It will be tried again,” he told a reporter that day. “When is the question.”

***

Epilogue

Cue “Is She Really Going Out With Him?”

Only one person besides Jack Coons knows the extent to which Ryan was involved with the California voucher initiative: U.S. Congresswoman Jackie Speier.

Speier, Ryan’s aide in 1978, accompanied the representative to Guyana. She was shot five times and left for dead. Elected to Congress in 2008, she represents much of the same stretch of the San Francisco Bay area that Ryan did.

The other Ryan aide who met with Coons, G.W. “Joe” Holsinger, died in 2004.

Ten weeks after redefinED contacted Speier’s office, her press secretary said the congresswoman was too busy to talk about the ballot effort.

Speier is a Democrat who has been endorsed and financially backed by teacher unions. But she has played little role in shaping education policy, either in Congress or during an earlier stint in the California State Assembly. In 2000, she opposed a conservative-led ballot initiative to create a statewide voucher program in California (so did Coons), but her opposition to school choice has never been particularly public or strident.

Many others who may have had insight into what happened in 1978 and 1979 are either gone, or won’t talk, or can’t be reached. Among them:

Congressman Ryan’s daughter Pat, a former executive with the California Healthcare Association, did not return calls. Former Los Angeles Times reporter Jack McCurdy, who covered the ballot effort more than any other journalist, couldn’t be reached.

Wilson Riles, the state superintendent at the time of the ballot effort, died in 1999. Ralph Flynn, executive director of the California teachers union at the time, died in 1995. Raoul Teilhet, the union president, died in 2013. Al Shanker died in 1997.

Henry Lucas, a black dentist in San Francisco who was described in news stories as an advocate for the ballot measure, died in 2009. Another visible supporter, Berkeley Law Professor Leonard Ross, died in 1985. The campaign consultant, Sanford Weiner, died in 1991.

Michael Kirst, president of the California State Board of Education from 1977 to 1981, was reappointed in 2011 by Gov. Jerry Brown and is again president. He said in an interview he was not aware of Ryan’s interest in the Coons-Sugarman plan, but said it wouldn’t have mattered. Voters would have never taken a “plunge into the unknown,” he said.

Carol Ruth Silver, a former Freedom Rider and former member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, was part of a Northern California contingent promoting the ballot initiative. She said in an interview she can’t recall details. But she looks back on the initiative as politically progressive and “the first disruptive idea to come out of Northern California.”

Nothing like Coons-Sugarman has been tried since, in California or beyond.

Since 1980, nine voucher or voucher-like proposals have made it on to state ballots, including in California in 1993 and 2000. None included the regulations Coons and Sugarman thought necessary to help low-income and working-class families. All lost by wide margins.

Full disclosure: The author is employed by Step Up For Students, a nonprofit which hosts this blog and helps administer two educational choice programs: Florida’s tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in America, and Florida’s Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts program, its education savings account for students with special needs.