Florida continues to be a national leader on college-caliber Advanced Placement exams, fueled by the success of growing numbers of low-income students.

The Sunshine State ranks No. 4 in the nation in the percentage of graduating seniors who have passed at least one AP exam, according to 2016 data released in a new report from the College Board, the nonprofit that administers the AP program.

At 29.5 percent, Florida outpaces the national average of 21.9 percent and trails only Massachusetts, Maryland and Connecticut, states with far fewer low-income students and far better academic reputations.

AP exams are standardized tests that correspond with dozens of college-caliber high school courses. They are widely viewed as a good gauge of a student’s college readiness and, in some credible quarters, as a good indicator of a state’s educational quality.

The latest results aren’t a fluke. The percentage of graduating seniors passing AP exams in Florida shot up 11 percentage points between 2006 and 2016, putting the state No. 3 in progress over that span. In raw numbers, 47,242 graduating seniors from the class of 2016 had passed at least one, nearly double the number from a decade ago.

Florida’s outcomes are even more impressive given its demographics. Florida has the highest rate of students eligible for free- and reduced-price lunch among states in the AP Top 10, and in most cases, a far higher rate. No state has a bigger differential between the relative poverty of its student body and its overall performance on AP exams. (See chart at the bottom of the post.)

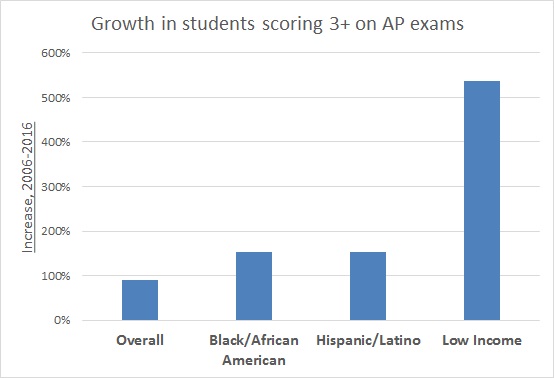

Additional AP numbers from the Florida Department of Education show low-income students are leading the charge. The percentage of low-income graduating seniors who passed an AP exam climbed more than 500 percent between 2006 and 2016, and that group made up more than 60 percent of the total growth in AP-passing graduates, according to DOE figures.

The number of low-income Florida students who passed at least one AP exam grew by more than 500 percent between 2006 and 2016. Source: Florida Department of Education data.

by Perry Athanason

Cristina Valdes noticed her fourth-grade son’s interest in learning start to fade and his behavior slip during the 2011-12 school year at their local elementary school and immediately took it as a red flag.

Instead of concentrating on his teacher’s lessons, Jordan Garcia asked to take unnecessary bathroom breaks, roamed the halls and fooled around seeking attention, his mother said.

“Jordan’s conduct at school had reached a crossroads and I saw him pulling further away from his interest in school and more towards acting up and being the class clown,” said Cristina. “I felt that if I did not intervene now, I may lose him by the time he started middle school.”

What perplexed Cristina the most was that her son’s grades were among the best in his class, but Jordan’s conduct and a general lackluster for his studies blemished that academic success. What she learned was that her son was often the first in class to finish tests and schoolwork and then he was left without anything structured to do. Jordan didn't notice his slide, however, but admitted he was bored in school.

“I found my work very easy and since the teachers didn’t have anything else for me, I would make paper balls and try to make three-pointers into the garbage cans,” said Jordan, now a sixth-grader. “My classwork was not very challenging and the homework was easy.”

Cristina also pinpointed the issue and tried to address it.

“I would review his assignments and I saw a lot of repetition in his curriculum. He simply wasn't being challenged academically. I met with his teachers on several occasions which validated what I already knew – my son was a smart kid, but was bored, which lead to a change of attitude and the beginnings of bad behavior,” said Cristina. “

At one point, she had her son tested for the gifted program, but he missed that option by just a few points, she said.

When Cristina was searching for options, a friend told her about the Step Up For Students school choice scholarship program, eventually leading her to Highpoint Academy near their Miami-area home. (Step Up co-hosts this blog.)

“I was thrilled after meeting with Highpoint Academy,” said Cristina. “They represented what I had envisioned for Jordan’s education including interactive teaching methods, small student-teacher ratios and a curriculum that I knew would challenge my son.” (more…)

Between 2003 and 2012, the number of low-income graduating seniors passing at least one AP exam climbed from 32,523 to 120,254. That’s an increase of 270 percent. That’s amazing.

Every few months, a major media outlet writes an expose about Advanced Placement classes. The stories (like this one and this one and this one) question the success of large-scale campaigns to expose minority and low-income students to the rigors of AP, using a jumble of numbers to make their case. Unfortunately, they’re often unfairly selective and tend to ignore an undeniably inspiring trend: More poor students are taking and passing AP courses than ever before.

I covered the AP push as a reporter in Florida. There’s plenty that merits scrutiny. I don’t think AP is the end-all, be-all. But on balance, the evidence suggests it has been a good thing - and the kind of good thing public school champions should be the first to highlight.

In the Florida case, public schools showed they can be responsive to low-income kids. For decades, and for no good reason, low-income kids were denied access to college-caliber AP classes, the nearly exclusive domain of white kids in the ‘burbs. So better late than never, schools in the Sunshine State opened the doors, raised expectations and gave students and teachers extra support.

I don’t know off-hand what the AP numbers are like from state to state; I don’t doubt some states have done a better job than others. But the national numbers, like the ones I got to know pretty well in Florida, suggest a lot of positive.

So I’m stumped as to why many stories are so negative – and why they leave out key numbers. The recent Politico story noted that between 2002 and 2012, the pass rate on AP tests fell from 61 percent to 57 percent. That’s true. But the story minimized the fact that because of vastly higher participation rates – and the success of so many of those new participants – hundreds of thousands of additional students are not just taking the tests every year, but passing them.

Forgive me while I highlight my own jumble of numbers: In 2002, 305,098 graduating seniors in the U.S. had passed at least one AP exam. By 2012, the number was 573,472. That’s an 88 percent increase. That’s excellent.

The numbers for low-income students are even more impressive. Between 2003 and 2012 (2002 figures were not available from the College Board), the number of low-income graduating seniors passing at least one exam climbed from 32,523 to 120,254. That’s an increase of 270 percent. That’s amazing.

Passing an AP test is a pretty good indicator those kids are college ready. More important, it shows they belonged in those classes all along. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the fourth and final post in our series commemorating the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Dr. Vernard Gant is director of Urban School Services with the Association of Christian Schools International.

by Vernard T. Grant

As the nation marks the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream" speech, speculation abounds as to what the content of that speech would be if delivered today. It is noteworthy that in all of his speeches and writings, Dr. King had little to say about education beyond segregated schools and low performance by black students. He apparently thought that once the racial barriers of discrimination and social injustices were removed, educational disparities would self-correct. It would not be much of a stretch to suggest he would be appalled to discover that according to the latest NAEP report, black children in 2011 are still not performing in reading at the level of white children in 1970 (just two years after his death).

Here’s my take on what his reaction would be, a slight variation on the words from his speech: It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro [children] a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of [educational] justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of [educational] opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check -- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of [educational] freedom and the security of [educational] justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. [Brackets mine]

Just as in the days of the civil rights movement, a grave injustice is transpiring today that is adversely and profoundly impacting its victims. A quality education, essential for cashing the promissory note that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, is being systematically denied families that do not have the economic means to secure one for their children.

A quality education is a purchased commodity. It depends on the financial wherewithal of individual families. It can be purchased either by paying tuition to private schools, or by paying higher mortgages and property taxes in neighborhoods with high-performing public schools. Parents who have low and moderate incomes simply do not possess the financial means to secure such an education for their children. They are bound to accept what is offered in schools assigned on the basis of where they live. They have no choice and no freedom in their children’s education. To compound matters, they are often told, from the public’s standpoint, that they should never have a choice because if they did, it would financially cripple the public school system. Translation: the important thing is not the best interest or well-being of the child, but the best interest and well-being of the system.

To add insult to injury, parents are told this by opponents of school choice and educational justice, all of whom exercise choice in where their children go to school. As a general rule, people of means naturally send their children to schools that effectively educate them. No caring parent (no matter how dedicated to a cause) would put their child in a school and sacrifice his or her education on an altar they know would fail their child. The tragedy is in the hypocrisy; what these individuals practice personally (school choice for their own children), they oppose politically for other folks’ children. They act in the best interest of their children, but insist the children of less economically advantaged families remain bound to a system that does not benefit them but rather benefits from them.

What is needed today and what Dr. King would call for is educational justice. (more…)

Editor's note: This is the second in our series of posts commemorating the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Darrell Allison is president of Parents for Educational Freedom in North Carolina.

Is school choice the civil rights issue for the 21st Century? I say it’s always been an issue.

While the battles, faces, and nuances have changed, we are still wrestling with core questions of equality, education as a means of opportunity, and creating a just society.

On Feb. 1, 1960, four young men from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Ezell Blair, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, and David Richmond, were refused service at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. because of the color of their skin. In response, they turned the nation’s attention to injustice and inequality by remaining in their seats until closing time. The sit-in continued the following day; pretty soon, after significant media attention, sit-ins were happening elsewhere in North Carolina and in cities across the South.

In 2013, four courageous young men followed in their footsteps by bringing attention to educational injustice to the North Carolina legislature. Reps. Marcus Brandon and Ed Hanes (both Democrats), and Brian Brown and Rob Bryan (both Republicans), each took political hits and overcame harsh rhetoric as they jointly sponsored The Opportunity Scholarship Act.

Opportunity Scholarships give students from low-income and working-class families the ability to attend non-public schools that could better meet their needs. The hard reality is, not much has changed since the 1960s when it comes to educational choices. Wealthy parents have always had access to an array of options that many lower-income, mostly minority students do not. This was the justification behind Opportunity Scholarships - to provide the same equality of choice to poor families.

As Dr. King once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere … whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” In North Carolina, we have a 30 percentage point achievement gap between non-poor and economically disadvantaged students, a 30 point gap between whites and blacks, and a 24 point gap between whites and Hispanics. If we treat Dr. King’s quote as truth and not a catchy saying, where is the moral outrage?

These statistics reveal a great divide – one that Brown v. Board of Education sought to address in 1954. The landmark case recognized segregation in public education was wrong. However, I contend that Brown v. Board was not simply and narrowly about placing black kids in classrooms with white kids. It was, at its very core, a school choice issue because one of its underlying premises was the quality of education was not the same for minority students compared to their white counterparts. (more…)

Fifty years ago next week, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech to 250,000 people in Washington D.C. It remains one of the greatest speeches in American history, offering a sweeping vision of hope and equal opportunity in the midst of so much fear and turbulence.

Many of us will reflect on how far we have come, and how far we have to go, since Dr. King energized millions with his words - and there’s no doubt education will be part of those discussions. To that end, we’re running a series of posts next week on the Dream and our schools.

Many of us will reflect on how far we have come, and how far we have to go, since Dr. King energized millions with his words - and there’s no doubt education will be part of those discussions. To that end, we’re running a series of posts next week on the Dream and our schools.

We asked our bloggers to consider a scenario described by education leader Howard Fuller: On Feb. 1, 1960, four black students sit down at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. and are denied service. They spark the lunch counter movement, helping to focus the nation’s conscience on racial segregation. Now, four black students sit down at a lunch counter and they’re welcomed like other diners. But they can’t read the menu.

What do racial achievement gaps say about the state of Dr. King’s dream? How does our current education system expand or contract his vision of social justice and equal opportunity? Is there reason to be hopeful when it comes to school choice, educational quality and the academic success of low-income and minority children? Please join us, beginning Monday, to read what some of our bloggers have to say. And please add your thoughts to the discussion.

Tuthill: The obstacles we face trying to improve public education, especially those related to generational poverty, are daunting. But I’m optimistic about the progress we’re making.

The latest Florida Department of Education report on the tax credit scholarship program, and my summer discussions with scholarship parents, students and teachers, have led me to some conclusions. These thoughts are not new, but sometimes it’s important to remind ourselves of things we know but occasionally forget.

Any fair and objective reading of the actual data in Florida public education has to begin with this acknowledgement: over the past 15 years, the state has made extraordinary progress across numerous key academic indicators.

Between 2011 and 2012, the number of Florida high school graduates passing college-caliber Advanced Placement exams jumped from 36,707 to 39,306 – a robust 7.1 percent. The increase wasn’t an anomaly. Florida ranks No. 4 in the country in the rate of grads passing AP exams. Over the past decade, it ranks No. 2 in gains.

These AP results are but one of the encouraging indicators of academic progress in Florida schools. But you wouldn’t know it from some of the media coverage, which often overlooks them and ignores or distorts the context. The same goes for a good number of critics. Many of them continue to be quoted as credible sources, rarely if ever challenged, despite assertions that are at odds with credible evidence.

In the wake of Education Commissioner Tony Bennett’s departure, some particularly harsh spotlights have been put on Florida’s school grading system and on former Gov. Jeb Bush, who led the effort to install it. I can’t defend some of the recent problems with grading (the errors, the padding) and I do wonder whether there should be more value put on progress than proficiency.

But I have no doubt, from years of reporting on Florida schools, that school grades and other Bush-era policies nudged schools and school districts into putting more time, energy and creativity on the low-income and minority kids who struggle the most. I also have no doubt that those efforts, carried out by hard-working, highly skilled teachers, moved the needle for those students and the system as a whole. To cite but one example: Between 2003 and 2011, Florida comes in at No. 9 among states in closing the achievement gap, in fourth-grade reading, between low-income students and their more affluent peers. In closing the gap in eighth-grade math, it comes in at No. 6. But don’t believe me. Take it from Education Week, where those rankings come from.

To those who approach education improvement with an open mind: Isn’t it troubling that such stats are rarely reported? And isn’t it odd that they’re rarely commended by teachers unions, school boards and superintendents who should be claiming credit? (more…)

The latest report on academic performance in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program devotes historic attention to evaluating the students who enter and, later, leave. This is the first time this subset has been thoughtfully and empirically analyzed to determine who these students are, why they leave and how they perform once they return to public schools. The researcher's findings lend credible support to common sense: students who struggle seek other options.

The latest report on academic performance in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program devotes historic attention to evaluating the students who enter and, later, leave. This is the first time this subset has been thoughtfully and empirically analyzed to determine who these students are, why they leave and how they perform once they return to public schools. The researcher's findings lend credible support to common sense: students who struggle seek other options.

The reasons that students transfer schools and how they perform can be overstated by supporters and opponents of the scholarship program alike. It is important to clarify the contradictory claims in this debate as more than 60,000 students enter the scholarship program this fall. The report, written under contract with the state by respected Northwestern University researcher David Figlio, faults neither the public schools nor the private schools, and simply asserts that students seek new schools because their prior option didn’t work for them.

For example, Figlio reports that for six consecutive years the students entering the scholarship program “tend to be the lowest performing students in their prior (public) school” and this is a “trend that is growing stronger over time.” This is not to say the public schools as an institution are failing low-income students, but more likely that the particular public school didn’t meet the unique learning needs of the child who chose the scholarship. Parents are seeing their child struggle and they are using scholarships to pursue new options.

The same could also be true for students who return to public schools. (more…)

A growing body of research suggests charter schools provide a good quality education relative to the traditional district schools from which their students transferred. This is especially true for low-income and minority students – the primary beneficiary of most charter schools nationwide.

A new report by Will Dobbie of Princeton and Roland Fryer of Harvard, shows significant achievement gains for low-income students in Harlem attending charter schools. Importantly, these low-income students are far more likely to attend college than their traditional school peers.

Even the CREDO report from Stanford University now states that charter schools, on balance, provide a slightly higher quality education. The study finds that students in poverty attending charter schools gain an extra 14 days of learning for reading and 22 days of extra learning in math. English language learners in charter schools gain an additional 43 days of learning in reading and 36 days in mathematics. The much misunderstood CREDO report in 2009 also found charter schools had a significant positive impact for students in poverty.

With solid academic achievement and a nationwide enrollment exceeding 2 million students, charter schools are gathering steam. So how do districts react when faced with competition from charters?

A new report in EducationNext, by researchers at the Walton Family Foundation and the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, attempts to answer that question.

The researchers selected 12 urban areas that had at least 60 percent minority student population and 60 percent low-income to create a more accurate comparison with the typical charter school population. They also limited their research to districts with a charter school enrollment that was at least 6 percent of the overall enrollment within the district. According to the article, Caroline Hoxby of Stanford University believes this threshold is high enough that districts will respond to competitive pressure.

After selecting the districts that met these criteria, the researchers combed through 8,000 newspaper articles to locate instances of districts reacting to competition from charter schools. When they discovered an example, the researchers reviewed district meeting minutes to uncover if and how the district responded.

They divided the responses into 13 action categories, some positive and some negative. Positive responses included replicating charter practices, collaborating with charter schools, creating pilot or innovation schools and expanding or improving school offerings. Negative responses included creating legal obstacles for charter schools, blocking access to facilities and using regulations to restrict choice and competition.

The most common response, found in 8 of the 12 districts, was to collaborate with charters. The most common negative response, found in 3 of the 12 districts, was to restrict access to facilities (i.e., refuse to share unused space or school buildings with charter schools). Overall, the researchers discovered that the districts had more positive responses than negative ones.

Overall this is a good sign, though more research needs to be done as charter schools – and the school choice movement – expand. School districts should always put students first, whether or not they educate the child. By collaborating with and emulating successful charter schools – rather than blocking and fighting – school districts can make an even bigger impact on student achievement.