Spending plans moving through the Florida Legislature in its final weeks have reinvigorated a familiar debate over how to help charter schools find money for construction. But the question of whether charter schools or districts schools are getting the most from an account called Public Education Capital Outlay is inherently misleading.

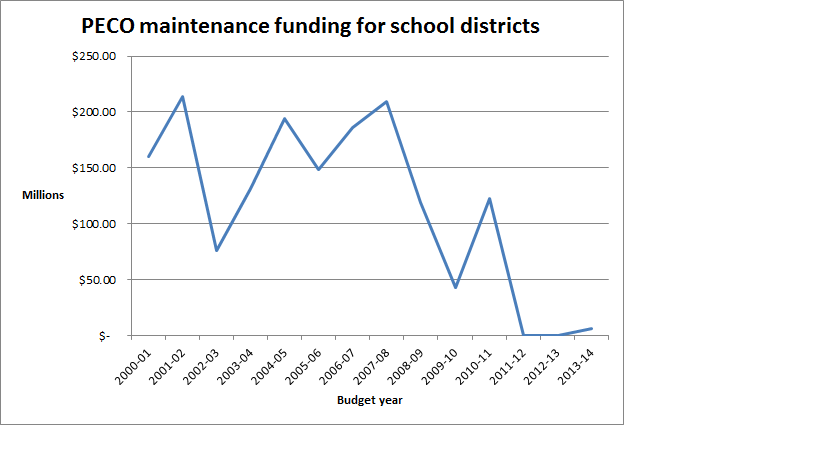

In the previous three years, almost all of the money allocated to K-12 institutions in the PECO fund, which helps pay for building maintenance and construction, has flowed to charter schools, fueling the contention that lawmakers have slighted school districts.

A group of Democratic lawmakers and PTA members appeared at a Tampa middle school on Monday, decrying what they called a “theft” that was “causing damage to our public schools.” Their rhetoric mirrors arguments made recently on the floor of the House and Senate, and speaks to a likely point of contention when lawmakers hammer out their competing spending plans during the remaining weeks of the legislative session.

But it also misses the full picture of facilities funding in Florida, of which the PECO money in the state budget is currently a small part. School districts raise billions of dollars each year in local revenue for capital projects, and unlike operating expenditures, that money seldom follows students who enroll in charter schools.

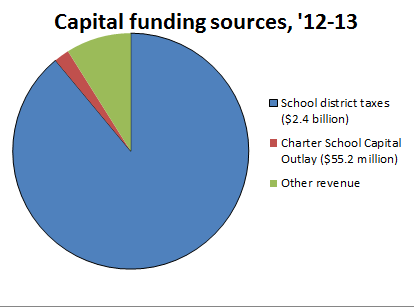

In the 2012-13 fiscal year, the most recent for which detailed budget figures are available, school districts raised more than $2.5 billion for capital expenses through local property taxes and other revenue sources, according to financial profiles published by the Department of Education. That same year, charter schools received about $55 million in state capital outlay money.

Sen. John Legg, R-Trinity, said charter schools absorb the costs associated with the students who enroll, even though they don’t receive all the funding that would otherwise accompany them. “There’s two sides of the equation,” he said. When people criticize the funding that flows to charter schools, “they only talk about one side of the equation.”

That’s one reason lawmakers have prioritize charter schools when they allocate increasingly scarce PECO funds. Legg and members of the legislative staff are running the numbers to compare the $91 million charter schools receive in the current budget with some $2 billion in local revenue for capital projects on a per-student basis. Their estimates show traditional public schools receive an average of slightly more than $800 per student for capital expenditures from property tax revenue alone, while charter schools receive an average of less than $500 per student.

That does not mean school districts and members of the Legislature don’t have a point when they complain about the state of funding for Florida’s school facilities or talk about the need for repairs. Funding for school district’s building needs has dwindled. And Legg is among the lawmakers who say there are other long-term issues with capital funding that should be addressed as charter schools in Florida continue to grow.

Charter school funding ‘equity’

The lion’s share of funding for capital improvements is controlled by school districts, and, for the most part, they do not share their local capital funds with charter schools. Lawmakers and blue-ribbon commissions have floated different proposals for sharing that money with charter schools, but none of the proposals has made it into law.

As a result, construction funding has become a priority for charter school advocates looking to close what Jon Hage, the CEO of Charter Schools USA, called the “equity gap.”

Charter schools receive between 95 and 98 percent of the basic operational funding formula for each public school student. But Hage said they receive only about 70 percent of the total amount a district spends, in operations, construction and facilities maintenance, for each student in a public school. His goal would be to increase the charter operators’ portion of the total amount to 90 percent.

“I definitely think that charter schools should be able to do more with less,” he said. “I don’t buy into this argument that says you should have 100 percent of the funding.”

PECO’s woes

There’s no question that school districts have suffered when it comes to capital funding.

When school funding reached its peak in the 2007-08 school year, districts brought in more than a half-billion dollars in PECO revenue from the state. Mid-sized districts like Leon County and Seminole County received nearly $7 million in state funding in a single year to supplement their local construction funding.

While operating funding has begun to recover since the recession, PECO funds for school districts have been stuck near zero. The PECO funding Scott and lawmakers proposed this year would still amount to a fraction of what was received during the economic boom.

That’s in part because the program is funded by a tax on land-line telephone connections, which has placed a drag on its revenue growth. But funds have also been scarce because the program maxed out its borrowing capacity (something Florida TaxWatch warned about in a 2011 report).

Even with revenue on the rise, the debt-averse Scott has been wary of selling more PECO bonds backed by the current revenue sources. He has also raised questions about a plan by Agricultural Commissioner Adam Putnam and a handful of Republican lawmakers that would create a new revenue source for capital projects at schools and universities.

Legg is among the lawmakers who say that as they grapple with ways to address schools’ capital funding needs over time, they will also need to look at ways charter schools spend that money — especially in the coming years, as Florida’s charter school sector continues to “mature. We will explore some of those ideas in a coming post.

Quick question? How many charter schools were forced to open by the state? I mean how dare we force them to open and then not give them the resources they say they need.