Many families whose schools were closed in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic or who erred on the side of caution about sending their children back to the classroom responded innovatively by forming learning pods – small groups of students led by a teacher or an educator guide.

Now that the crisis has passed, most students have returned to their traditional schools. But many of these innovative solutions have persevered, especially those serving Black families.

Black education leaders who discussed the issue at a recent forum agreed that these tiny private schools are now an established alternative to traditional schools, which they say have failed their children.

Among six participants in a webinar sponsored by the Center on Reinventing Public Education – a group studying the role of learning pods – was Robert S. Harvey, former superintendent of a charter school network in East Harlem, New York, and now president of FoodCorps, a nonprofit dedicated to child nutrition.

Other panelists included Maxine McKinney de Royston, associate professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Jennifer Davis Poon, a partner of learning design and sense-making at the Center for Innovation in Education, a national nonprofit that works with education leaders to promote inclusion; Janelle Wood, founder and president of the Arizona-based Black Mothers Forum; Lakisha Young, founder and CEO of The Oakland Reach; and Chris “Citizen” Stewart, CEO of brightbeam, a national network of education choice activists that produce Ed Post.

The webinar focused on what public education can learn from Black-led alternatives to traditional education, posing questions such as whether such initiatives should exist within the traditional system, which is where about 85% of Black students remain, and whether these alternatives, including homeschooling, which shot up from 3.3% to 16.1% during the pandemic among Black families, promote resegregation.

Oakland Reach founder Young said that’s the reason her organization chose to work within the traditional framework post-pandemic. The group trains parents as tutors, which it calls “liberators,” to help students with academics.

The nonprofit also provides community support, social-emotional enrichment, tech training and economic development. During the early months of the pandemic, Oakland Reach mobilized to set up a virtual hub for students without internet access.

“Our motivation for building outside of the system is because we saw our system crumbling in the midst of the pandemic,” Young said.

Now that the threat has passed, she said, the group is putting caring people out in the community and requiring that the system “re-engage with us in a different kind of power dynamic.”

Contrast that response with Black Mothers Forum, which maintained its small learning environments after traditional schools reopened.

Wood founded the forum in 2016 to provide support to Black parents who believed their children were disproportionately disciplined in district schools. When the schools closed, the Phoenix group opened small groups to educate students whose parents had to work and could not supervise remote learning.

Wood said the parents are happy with the small schools because “they aren’t being called in the middle of the day to pick (their kids) up for minor, minor infractions.”

“Our children were being criminalized and demonized for behavior that was normal for their age group,” she said.

Providing further impetus for the small schools to stay open is Arizona’s rich education choice policy, which offers state funds and makes the schools free for students. This year, Gov. Greg Ducey made history by signing into law a bill that grants education savings accounts to any student who wants one, putting Arizona on the map as the first state in the nation to do so.

But Stewart pointed out that in states that don’t provide education savings accounts, such programs are out of reach for Black students, whose families can’t afford to pay out of pocket. Harvey added that Congress’ refusal to make the expanded child tax credit permanent also deprives families of modest means a potential way to fund education alternatives.

As for whether Black-led alternatives contribute to resegregation, Wood and de Royston responded that Black children, especially boys, already were suffering from discrimination in the system. De Royston called blaming Black parents for resegregating school “a particular form of gaslighting,” especially when white middle class communities already have done that by seceding from urban school districts.

Her comments come as more and more Black parents are growing vocal about concerns over the quality of their children’s public schools. In Baltimore, a Black couple is suing the city school system for mismanagement of funds over accusations about the enhancement of attendance and grades for funding purposes.

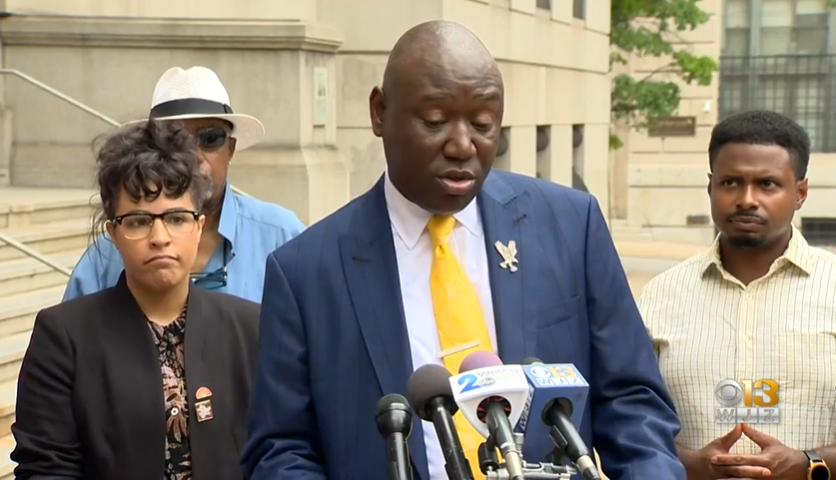

In June, an inspector general’s report showed that 12,552 failing student grades were changed to passing between 2016 and 2020. The report prompted Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan to call for a criminal investigation into the matter. The case, which drew national attention, prompted civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who represented families in the Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and Flint, Michigan, cases, to join the case.

“We knew that Black people were struggling in American schools, but we didn’t know much until we opened those systems up to public scrutiny,” said Steve Perry, head of school and founder of Capital Preparatory Schools, a group of charter schools in the Northeast.

Perry was interviewed on Revolt Black News for a segment called “Black America’s Education Epidemic” in which he said the system has failed Black students since the early 20th century.

“It isn’t a new thing,” he said. “Black people have been trying to find ways out of the system that was designed to undermine their very growth and humanity.”