by Allison Hertog

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings – they have the same parents but are often rivals – vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings – they have the same parents but are often rivals – vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

In most states, charter schools have the option of freeing themselves from these and other disputes by essentially becoming their own districts (legally termed Local Education Agencies or “LEAs”). But the vast majority of charters, even in states like California, where they have the option of becoming their own LEAs, have not taken on the responsibility of fully controlling their own special education programs – possibly out of fear, ignorance or politics. Fortunately, many of the more competent and high-achieving California charters – like KIPP, Aspire, and Rocketship – have chosen the path of autonomy and accountability and are leaving behind special education disputes with districts.

Where I work in Florida, where essentially charter schools don’t have the option of becoming their own LEAs (as is also the case in places like Virginia, Maryland and Kansas, and in New York for special education purposes), these special education disputes are problematic for many reasons. They’re terribly inefficient; they come at the expense of children; and they fly in the face of the charter school movement’s supposed commitment to autonomy and accountability.

To illustrate why it makes sense that some of the most competent charters are choosing to become their own LEAs and take full responsibility for special education, I’m going to use a business analogy that doesn’t carry the emotional baggage of disabled children.

Imagine a young entrepreneur who runs a new and successful Italian restaurant called “Vagare.” Vagare (i.e., the charter school in this story) has grown to serve roughly 300 customers a day. But in this city there’s a local corporate giant: “The Italian Restaurant Company” (i.e., the district). Founded in the late 1800’s, the IRC has virtually cornered the market on Italian restaurants. It serves thousands of customers daily, owns hundreds of locations, and controls restaurant supply firms and food supply chains. You get the picture.

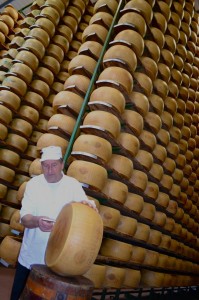

The IRC has contracted out some of its locations and provides certain supplies to Vagare and other smaller restaurants. Vagare locally sources most of its ingredients except for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, which, by contract, it is required to obtain from the IRC, which buys it in bulk from Italy.

Authentic Parmesan (i.e., special education services) is difficult and expensive to produce. It’s only exported from three Italian provinces following a government-mandated process which includes feeding cows with dehydrated summer grass during the winter months. Vagare’s owner has become increasingly frustrated with relying on the IRC to get Parmesan that is of variable quality and not always delivered on time. Some customers have even filed claims that the cheese made them ill. Even though technically the IRC and not Vagare is liable for those claims, Vagare wants out of its contract to buy Parmesan via the IRC. Vagare wants to deal with the Italian suppliers directly, despite the need to hire someone who speaks Italian and other complexities.

The IRC doesn’t benefit from this relationship either. Why would it want or need the added burden and liability of providing Parmesan to Vagare, a competitor? Rational business people would easily cut the cord, right? Right.

While it’s not as simple (nor as rational) for a charter school to become the LEA taking full responsibility for special education services as it is for Vagare to end its contract with the IRC, there are plenty of charters around the country that want that kind of autonomy and accountability. There are also districts willing to give up the control and the funds associated with providing special ed services to charters.

The high-achieving California charter schools I mentioned are perhaps the most successful to date because they have banded together. They use the existing state organizational structure to create a consortia of charter LEAs. Together, they are jointly responsible for the development of special education policies and procedures, distribution of federal and state special education funds, and provision of a range of special-ed-related professional development options.

Following legal action, other similar consortia have developed, allowing charters to become their own LEAs in D.C., Colorado and New Orleans, for example, so they can approach the economies of scale that large districts have. In 2011, the Los Angeles Unified School District, the second largest district in the nation, reorganized to provide charter schools a new level of autonomy and flexibility while providing them support and resources to ensure they can effectively serve a wide range of students – even the severely disabled.

The aim of some of these charter schools is bold and admirable. They’re not breaking away from districts simply to replicate the existing broken system of special education. They’re trying to create communities of charters that truly provide innovative, high-quality educational options for students with disabilities.

Great explanation Allison. I believe however that Florida does indeed have charter schools in Lake Wales that have joined together to become their own LEA. Robin Gibson, our attorney helped facilitate that LEA.

Nonetheless, I’m in the mood for some tortellini. Kudos!

Dear Henny,

Yes, that’s true that there is at least one charter in Lake Wales which is its own LEA. That’s why I qualify my statement about Florida charters not having the option of being their own LEA with “essentially.” However, the FL charter school statute is so restrictive that it effectively limits LEA status to that single situation. Not sure why that is.

Tortellini sounds great, though. 🙂

Allison