A new report argues supporters of private school choice can learn from public charter schools and should look for ways to "break down the walls" between the two sectors.

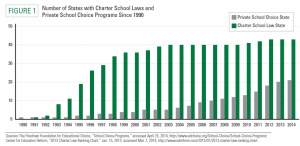

While most states have authorized charter schools for more than a decade, private school choice programs are starting to become more widespread. Chart from the Friedman Foundation's report.

Private school choice programs serve only a few hundred thousand students nationally, a fraction of the 2.3 million enrolled in charters. But more states have created tax credit scholarship and voucher programs in recent years, and existing programs, including the tax credit and McKay scholarships in Florida, are growing.

A report released this morning by the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice argues that as private school choice programs grow and proliferate, they can draw a few lessons from the charter sector about how to create more quality options for students.

Report author Andy Smarick - a consultant at Bellwether Education Partners who's among the leading proponents of a "three-sector approach" to education reform - writes that private schools could learn from charters' use of networks and incubators to improve their operations. He also advocates for a charter-style approach to accountability, in which participating schools get screened by authorizers — agencies that hold them to performance-based contracts in exchange for more freedom to operate.

That idea may prove controversial among private schools that have traditionally not seen as much regulation as their publicly funded counterparts. But as states debate how they will regulate private school choice programs, Smarick writes that authorizers would be in a position to fine tune their judgement calls about how private schools are evaluated. For example: Should they be publicly accountable for the performance of all their students, or just the performance of students who receive tuition subsidies through tax credit or voucher programs?

"The contractual relationship, if implemented properly, will also be more nuanced - rendering fairer judgments and respecting the unique characteristics of private schools - than, say, a single letter grade for a school that would be generated via a state’s accountability system," he writes.

Other insights from the charter sector are more straightforward, such as the use of incubators and networks.

Charter networks like the award-winning KIPP schools are able to pool resources, relieving principals of tasks like purchasing or bookkeeping and allowing them to focus more on academics at their schools. They're also in a better position than individual schools to create internal talent pipelines and tap national fundraising networks. Smarick argues parochial schools could benefit from taking a similar approach.

Catholic schools, about 70 percent of which are controlled by local congregations, have begun creating networks outside the traditional parish and diocese-based models. Smarick cites the Cristo Rey Network of Catholic high schools. Another effort to create more high-quality urban Catholic schools, Notre Dame's ACE Academy network, is active in the Tampa Bay area.

On the whole, Smarick finds a "glaring lack of collaboration among high-quality schools from the charter and private school sectors," and argues changing that will open more opportunities for students to attend quality schools.

"By making use of successful elements of the charter sector, the private school sector can help break down the walls separating the two, enabling a more agnostic view of schooling sectors, particularly urban ones, defined by quality and service to students," he writes.