When the words fail the social critic, there always remains some “inequality” to be cursed. Our numberless differences provide the happy hunting ground for those us seeking either to praise or damn some aspect of American reality. The abstraction that is equality provides the gauge of justice for those differences we lament in the lives of Bill and Sally. Bill owns a plane; Sally, buses. Sally is robust; Bill is crippled. Bachelor Bill is a one-percenter; single mother Sally struggles. Bill is a man; Sally isn’t. Comes then The Word: Any difference in kind or degree can raise an issue of egalitarian injustice. It seldom occurs to us that, were we all to be made equally ill or impoverished, it would be difficult to claim that justice has advanced; the dead world of “On the Beach” was thoroughly equal. Equality of our objective condition is in itself, irrelevant.

When the words fail the social critic, there always remains some “inequality” to be cursed. Our numberless differences provide the happy hunting ground for those us seeking either to praise or damn some aspect of American reality. The abstraction that is equality provides the gauge of justice for those differences we lament in the lives of Bill and Sally. Bill owns a plane; Sally, buses. Sally is robust; Bill is crippled. Bachelor Bill is a one-percenter; single mother Sally struggles. Bill is a man; Sally isn’t. Comes then The Word: Any difference in kind or degree can raise an issue of egalitarian injustice. It seldom occurs to us that, were we all to be made equally ill or impoverished, it would be difficult to claim that justice has advanced; the dead world of “On the Beach” was thoroughly equal. Equality of our objective condition is in itself, irrelevant.

Of course, early differences can, in fact, alert us to injustice, but not because we are, or should be, equal, but because some particular type and degree of difference merits that special regard that one owes his fellow human. The sceptic, of course, can doubt that one owes anything to anybody; but it is no answer to him that we are unequal. True, almost by definition, any duty to others will ordinarily involve differences of some sort; but nothing is clarified by invoking The Word. Mere difference is an empty moral vessel.

It may not in all cases seem an empty political or legal vessel. The state may act simply to reduce socioeconomic difference hoping, for example, to diminish hostility between groups. But notice that the word “thereby” signals a separate and immediate cause of the state’s concern quite distinct from inequality; the group antipathy may well have originated, not from difference, but from some irrelevant historic score. Quite the same holds in private law: A poor man recklessly injures me; our difference in wealth – and, perhaps, his jealousy – are irrelevant to the issue of his responsibility.

Equality, simply as such, has been hard for the critic to defend as a demand of justice. Seeking coherence, some philosophers would substitute “fairness” as the goal; that word may not tell us much, but at least it rejects sheer difference as our favorite object of suspicion. If we could distinctively improve the condition of the most miserable citizen by simultaneously making Bill Gates richer, even John Rawls might be satisfied.

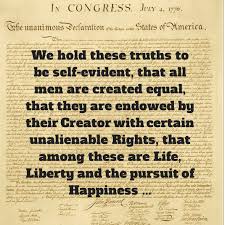

Were the Founders, then, engaging in mere word play when they declared us “created equal.”

After all, 11 years later, almost the same company of men were to put their names to a document that protected human slavery. Some were themselves slavers who decisively rejected equality of social station. How could this “created” form of equality be taken seriously? Only if the word “equal” in the Declaration refers to some reality of human nature quite apart from differences in our civil status, wealth, and opportunities. The concept must be taken to identify some one crucial and universal human reality, identical in each of us, one which neither shrinks nor grows with time and circumstance – even the condition of bondage. The slave may freely choose to seek the good as he is able to find and engage it –and thereby confirm his own destiny.

Given the Founders’ resort to the Creator, it is difficult to ignore the theological dimension. The Declaration is an invocation of the God who apparently created us equal in some particularly crucial sense. Every human knows – he just knows – that he is responsible, and indeed invited, to look for the good; and that is our defining task. But, it is, indeed, only an invitation; we are free to decline and serve ourselves instead of divine authority. We accept the invitation by seeking the objective good and attempting to realize what we find. We make mistakes. But, as the current pope seems to think, our honest errors about the good do not corrupt the self that is truly seeking the right way.

Our vocation, then, is to seek the good and realize it as best we can. Anyone can do it. It is a picture of mankind as free and responsible creatures, either seeking the Creator’s will or, instead, doing it my way. The choice has consequences here and hereafter; I doubt the Dante version of the latter, but that is not our subject.

Would this transcendental egalitarianism of the Founders bear in any way upon the practical hope for the expansion – the universalization – of school choice?

If we all believed it, I suspect it would. If Baptist, Evangelical, Muslim, Catholic, Jewish all saw a man’s best effort as the way to eternal salvation, a politically cohesive union of minds could become a powerful national engine for change. Why is that necessary? Because historically it has seemed to many that access to God was seriously affected by particular creedal commitments. In some quarters, this was a matter of fortune; there was not bi-lateral exchange; God did it all. In others, a person was to be judged by his works – in still others, simply by his belief. The Founders seem to assume universal access to God, though I doubt that the free new American of 1776 could be passive in deserving the relationship. He must strive to find and serve the good.

A national religious consensus – not necessarily unanimity – on mankind’s equality of access to God irrespective of creed (or of no creed) would largely defang the ideological objections to the subsidized choice of religious schools. Much of that ugly discourse insists that religious instruction tends to disunite, even though all the evidence is to the contrary. A solid and well-displayed allegiance of church leaders to the Founders’ insight would be a great contribution to both the political side of achieving choice and to the coming and inevitable judicial challenges to the exclusion of religious schools from the widening charter sector in so many states. Is government in this country entitled – in spite of the First Amendment – to help all schools except those who would teach the Founders’ belief that it was God who made us equal?