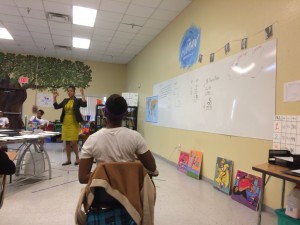

I recently talked with some sixth-graders at a small, upstart private school in a low-income neighborhood in Central Florida. I think I learned more from them than they did from me.

This was in a neighborhood where one in four adults over 25 hasn’t finished high school. The sixth-graders kept asking me about colleges. Someone had planted in their minds the idea that was in their future. “They’re beyond capable,” one of their teachers told me. “Their dream is not a fantasy.”

Their teachers believed in them. And that matters.

The importance of belief has been getting increased attention in education circles. The reality is that too many children are confronted by institutions and adults that systematically short-change their potential.

It was thrown into stark relief recently by the Tampa Bay Times/Miami Herald Tallahassee Bureau, which documented the journey of Florida’s Senate President, Andy Gardiner, and his wife, Camille, who set out to provide opportunities for their son, Andrew, who has Down syndrome.

Along the way they encountered no small number of adults who saw limits on their son’s abilities. He was turned away from schools for seemingly absurd reasons, like the fact that he couldn’t jump. As Camille Gardiner said in the article, “When people meet him, they think more about what he can’t do than what he can do.”

Now, the Senate has approved legislation that will allow more children like Andrew to attend college. When you believe in the potential of every child, it has policy implications.

“There has been a ceiling for these students in the past,” bill sponsor Kelli Stargel said on the Senate floor. As the bill (which still awaits approval in the House) passed unanimously, she said, the state “just crashed through that ceiling.”

It’s not just children with special needs who have ceilings placed on them by adults who underestimate them. The problem is far more widespread.

Consider the studies showing black children are more like to be branded troublemakers. Or the children who told Robert Putnam, in his harrowing new account of growing up poor in America, that their teachers “don’t care if we learn or not.” Or the sense of helplessness that often chokes conversations about educating inner-city children.

We should be asking a simple question of those who work in our education system: Do you believe in the potential of every child?

You won’t get a straight answer by asking directly. But spend time in classrooms or with teachers, and clues emerge.

In the summer of 2013, I sat in on professional development sessions for teachers at Title I Elementary schools in Leon County. The teachers, who were taking time out of their vacations to prepare for the next school year, consistently repeated a theme: Their children, given the proper preparation, could meet the state’s more demanding education standards. Those teachers believed.

When I visited KIPP Jacksonville earlier this school year, leaders at the school told me that if their children aren’t making progress, the adults must change their approach. That’s a sign that they believed.

At a charter school on the edge of the Everglades, teachers and administrators talked about rejecting a “deficit mentality” for students who were still learning English. They wanted to use their students’ multilingual backgrounds as an asset, and design a curriculum aimed ensuring eighth graders would be able to perform at a high school level in two languages. They, too, believed.

I’ve met other educators who believed in their children’s potential, and started new schools in small towns that failed to meet state accountability requirements and were forced to shut down. Belief, while necessary, is not always sufficient.

Belief cannot be regulated or legislated into being. But parents and students can often tell whether they are being served by institutions that believe in their potential. If an institution doesn’t believe, they should be able to enroll their children in one that does.

Giving that option for every parent would place a new onus on our education system, and especially those who oppose policies that allow parents to choose who gets to educate their child. They would have to prove that they believe.