Recently, before the Florida Board of Education cast a vote that would shut down a Clay County charter school, a local activist said officials were making the right move. The school was so low-performing, he argued, that no matter where it's students ended up, they'd likely be better off.

Last week, Stanford University's Center for Research on Education Outcomes released a study that backs him up.

But the study also shows school closures can hurt students if they happen under the wrong conditions.

CREDO researchers looked at school closures in 26 states, including Florida, over seven years. They found officials tend to close public schools that are low-performing. But the closed schools also tended to serve disadvantaged children of color disproportionately, even among schools with similarly low academic performance. That, the study authors write, raises questions about equity in officials' decision-making.Overall, the study finds nearly half the students who left closed schools wound up in a higher-quality school the next year. Most of the rest wound up in schools with "equivalent" performance. Between one-tenth and one-fifth of the students wound up in lower-performing schools.

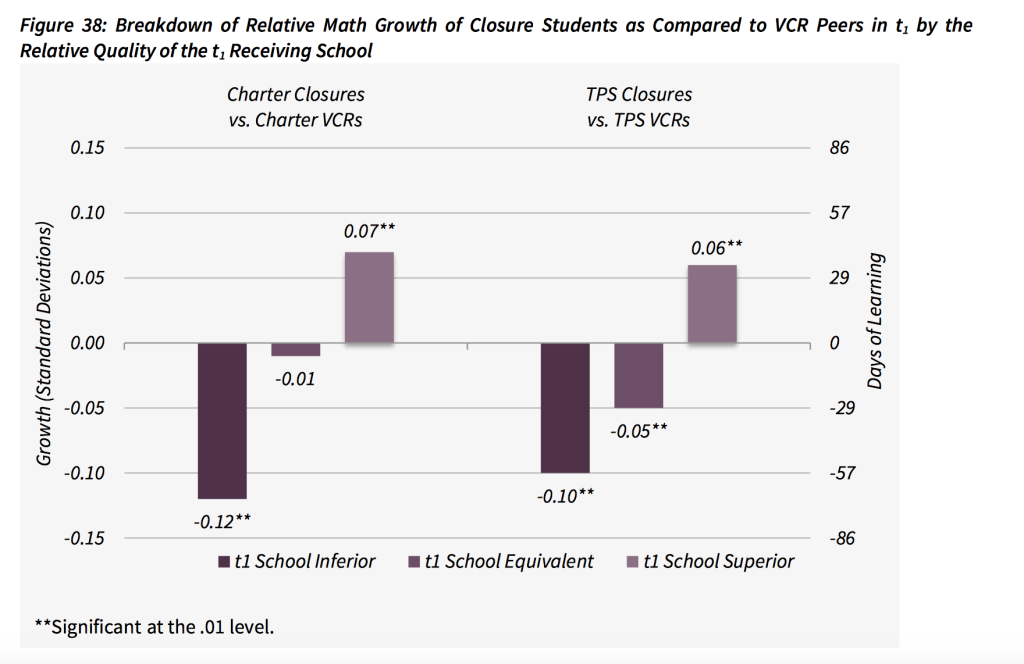

Where they wound up mattered a lot. Students who landed in better-performing schools saw their academic performance improve. But students who ended up in schools with similar or worse performance suffered significantly. Some of this was likely due to the stress that comes with changing schools.

In Florida, the study tracks 34 charter schools and 24 traditional public schools that closed between 2006 and 2013. There was basically no learning loss for students in the charter schools that closed. But students in the shuttered district-run schools suffered achievement losses in both reading and math.

This might give ammunition to supporters of Florida's "double-F" charter school law, which forces the lowest-performing charter schools to close automatically. The law provides a one-year safety valve for schools where students' learning gains outpace nearby schools. That could help ensure students in those schools don't wind up worse off.

But that might not be enough. Not every community looks like Clay County, where just about every district school is high-achieving.

Commentators like Neerav Kingsland and Greg Richmond of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers say the study underscores the importance of bringing new, better schools to more communities.

As Richmond noted in a statement: "The report’s finding that closing a school leaves half of students worse off — only because they lack a quality option — should inspire us to do more to open good, new schools."