Our current one-size-fits-all education system cannot provide every child with a high-quality education, no matter how much money we spend, because children are not standardized. They are unique.

Florida’s constitution requires the state to make adequate provision for a uniform system of free public schools that allows students to obtain a high-quality education. Back in 2009, a group called Citizens for Strong Schools filed a lawsuit asserting the state is not fulfilling this mandate, and asking the judiciary to order the state to make the necessary improvements. Both the circuit court and the appeals court ruled against the plaintiffs, but the case is still alive, with oral arguments in front of the Florida Supreme Court scheduled for Nov. 8.

Some argue that if we spend enough money our public education system will be able to meet this uniform, high-quality requirement. I disagree.

It’s customization, more than funding, that is the real key.

In a June 27, 1996 decision, the Florida Supreme Court defined uniformity in the context of the Florida Constitution:

“The Florida Constitution only requires that a system be provided that gives every student an equal chance to achieve basic educational goals prescribed by the legislature…Florida law now is clear that the uniformity clause will not be construed as tightly restrictive, but merely as establishing a larger framework in which a broad degree of variation is possible.”

If we adopt the court’s 1996 interpretation, and assume uniformity means all students statewide having equal access to a high-quality education, then, despite having one of the country’s most effective and efficient public education systems, Florida has more work to do.

To be effective, any significant new funding must be tied to needed systemic improvements. Our current one-size-fits-all system cannot provide every child with a high-quality education, no matter how much money we spend, because children are not standardized. They are unique. Consequently, we need a system that effectively and efficiently customizes education to the needs of each child by embracing the “broad degree of variation” the court referenced.

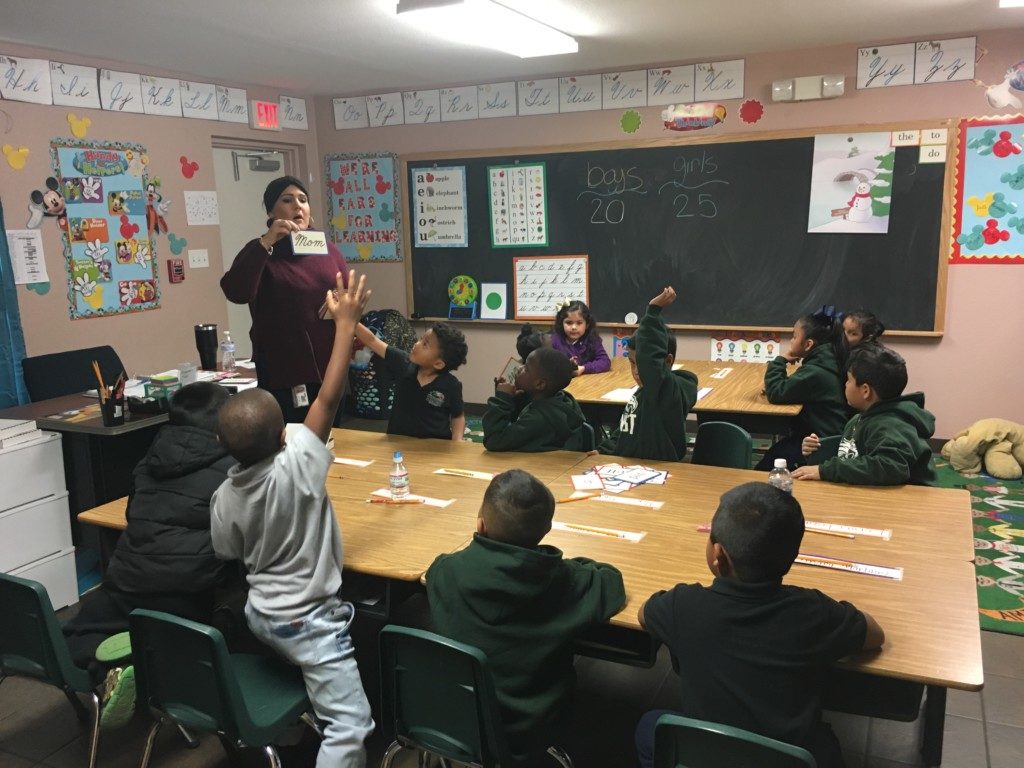

Providing every Florida student with a customized learning plan should be step one. Currently, school districts are only required to develop custom learning plans for children with unique abilities (i.e., special needs). Extending these plans, called Individual Educational Plans (IEPs), to all students will require time, training, and the appropriate technology to help teachers develop and manage these plans. Teachers will also need training in how to manage classrooms and other learning environments that are organized around customized instruction.

Next, we’ll need a process to determine how much funding is required to successfully implement each IEP. Low-income and unique abilities students now receive additional funding, but it’s not customized to the needs of each student. Not every low-income or unique abilities student needs the same amount to be successful. Identifying the amount each child needs will help us determine the annual public education budget – and offer a good indicator of what is “adequate.”

Once every child has an IEP and the public funds necessary to implement these plans, we’ll need to empower families to choose and pay for those providers who are the best fit for their child. Educational Savings Accounts (ESAs), which are now being used in the Gardiner Scholarship program for children with unique abilities and a new program for struggling readers in public schools, are good vehicles for doing this. (Both programs are administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.) ESAs function like health savings accounts. Once a child qualifies for a funding amount, a government agency transfers these public funds into an account that parents use to pay for government-authorized education products and services. ESAs are how parents will pay the various education providers who collectively are providing their child a customized education.

There’s more. Once families have the freedom and funds to purchase education products and services, they’ll need information and support to help them make the best decisions possible. Providing this information and support will require significant systemic improvements. We’ll need education counselors who are trained to assist families as they review their in-school and out-of-school options, and we’ll need data systems capable of providing feedback to parents and their counselors about which options have the highest probability of success. Just as more doctors and hospitals are relying on a branch of artificial intelligence called machine learning to help them customize the best treatment for each patient, parents and educators will increasingly be using machine learning algorithms to help make better education decisions for each child.

We could move towards this more sensible system of public education quicker if the Florida Constitution weren’t in conflict with itself. In my view, the constitutional provision mandating that school boards “operate, control and supervise” all public schools is an obstacle to creating a high-quality, uniform public education system.

State government can triple annual public education funding tomorrow and still not meet its constitutional mandate unless all of Florida’s 67 school boards agree to cooperate. That’s probably never going to happen. Eventually, Florida’s voters, its judiciary, or the federal courts will need to resolve this conflict. In the meantime, efforts to provide Florida students with an effective and efficient customized education will continue in isolated schools and classrooms statewide.