HUDSON, Fla. – All four of Patricia Larkin’s kids have special needs, and all were making good progress at HOPE Ranch Learning Academy, a private school known for its equine therapy program. So when the coronavirus pandemic forced the single grandma to briefly veer into homeschooling, she got a little panicky.

“My children have to be on a routine. And when our country came to a halt, we knew something was going to happen with the schooling,” said Larkin, 59, who is raising three grandchildren and a grandniece. “I tried as hard as I possibly could to do the routine, but I’m not a teacher.”

Two things came to Larkin’s rescue: School choice scholarships, which allowed her children to stay at HOPE even though she just got laid off as a property manager. And the school itself.

The HOPE Ranch staff of 43 rallied around a parent-shaped plan to tailor distance learning to their 150 K-12 students, most of them on the autism spectrum.

“We had to re-invent school in a week. Those were 18-hour days nonstop,” said Jose Suarez, the school’s founder and executive director. Given gaps with devices and connections, “We had to come up with a system that was low tech, that could be deployed regardless of whether there was a computer in the home or not, and could be deployed on a daily basis.”

The early result: Rave reviews from parents like Larkin, who called the plan “brilliant.” And high hopes for the next steps, including a virtual version of equine therapy, the school’s main draw.

Lead teacher Ms. Terri, top left, connects with HOPE Ranch students each morning in an online ‘Social Group.’

A key question in the dash to distance learning is the impact on millions of students with special needs. Some school districts, fearful of being sued by parents of students with disabilities for not providing equitable services, have put a hold on learning for all students. Others are moving ahead, but in ways that aren’t making parents of students with disabilities happy. This is hard, tangled terrain.

In Florida, a national leader in education choice, it remains to be seen whether charter schools or private schools do any better. Those 2,600-plus schools, serving 700,000 students, aren’t getting much coverage. Even if they were, it’s risky to draw generalizations from a few schools, given how diverse those sectors are, and how varied the challenges for students with disabilities.

Florida, though, does present a unique window. It has long offered learning options to parents of students with disabilities. In 1999, it created the McKay Scholarship, a voucher for students with disabilities that now serves 30,000 students a year. In 2014, it created the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs that’s now serving more than 13,000 students. (It’s administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Those scholarships help support a growing number of private schools that serve students with special needs, some of them exclusively. HOPE Ranch, nestled on an oaky stretch of sand hill an hour north of Tampa, is one of them.

Suarez said his team started discussions about remote learning in early March. But they kicked into high gear on March 13, when Gov. Ron DeSantis essentially ordered all public schools in the state to close. Staff quickly surveyed parents about digital capacity, and while not every family had enough computers or tablets for every child, they had phones that could suffice in the short term.

HOPE also asked parents to list their biggest concerns, and the parents were clear. We don’t want our kids falling behind, academically or socially. We don’t want them on computers all day. We don’t want to be their teachers.

The HOPE staff fashioned their plan on that input. Individualized learning packets would be distributed every week. Parents would be given a general schedule with deadlines, but with enough flexibility to figure out the best track for their kids. Using Google Hangouts, teachers would do a half-hour visual chat with each student at a set time every day.

The vast majority of Florida students returned to “school” on Monday, March 30. On Thursday and Friday of the prior week, HOPE teachers did trial runs with the chat platform. By Sunday night, Larkin’s kids were giddy. “They were, ‘I can’t wait! I can’t wait!’,” she said. “They knew they were going to see their teachers.”

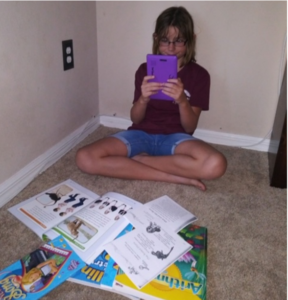

HOPE Ranch student Nicole connects with her teacher during a half-hour visual chat they have every morning.

Larkin’s boys – Chad, 12, and Jordan, 7 – are both autistic. Her girls – Bryanna, 10, and Nicole, 10 – are both diagnosed with ADHD and PTSD. All four struggled in public schools. But at HOPE, Larkin said, their teachers know their specific challenges, and work diligently on specific remedies. Jordan, for example, used to avoid “circle time” with classmates because of extreme shyness. But rather than trying to force him to conform, his teachers let him stay back until he felt comfortable. Eventually, he joined on his own.

Bryanna has struggled with maintaining focus. So how sweet it was, Larkin said, that on her first chat on her first day back, Bryanna stayed locked in. “I thought I was in the Twilight Zone,” Larkin said. “They engaged like they were person to person in front of each other.”

HOPE teacher Kevin Trevithick said for his 13 high school students, the quick shift to distance learning has been a lesson unto itself.

“It’s time to adapt and move forward,” he said. “That’s the biggest thing I’ve tried to convey to them.”

One student is resisting the chats, said Trevithick, a former public school teacher, but the others are having fun with the novelty of the situation and the new technology. One told him he’s not a morning person, and now that he can set his own schedule, he’s getting more done.

Can this new way of “school” work for long? Trevithick said some students may get tired of being cooped up. But “people are incredibly adaptable,” he said. “If it’s something where this is the way it has to be, then I do think the majority of them will do just fine.”

The can-do attitude is infectious. Parents like Larkin are having to quickly navigate platforms and apps they never heard of, like Calendly and Adobe Scan. But when they learn they can do it, she said, the next challenge looks a little less daunting.

In the meantime, more programming is coming. On Friday, HOPE is rolling out “virtual chapel” and a virtual social skills class, which will allow the students to stay connected and interact. On Monday, it will begin online speech, occupational and ABA therapy, led by local district employees assigned to the school.

Monday is also the kickoff for the “Virtual and Interactive Horsemanship” class. HOPE students learn to ride, groom and care for a stable of horses. Along the way, they learn teamwork, resourcefulness, problem solving – and get some boosts for their self-esteem. Larkin said the horses helped Jordan, her youngest, come out of his shell. “He mounts those horses … and he’s beaming,” she said. But can it possibly work wonders when it’s online?

It’s working with her kids in the other settings, Larkin said.

So why not?

Lead photo: Bryce, a student at HOPE Ranch, connects with his teacher, Ms. Suzanne, and his parents who joined from remote locations.