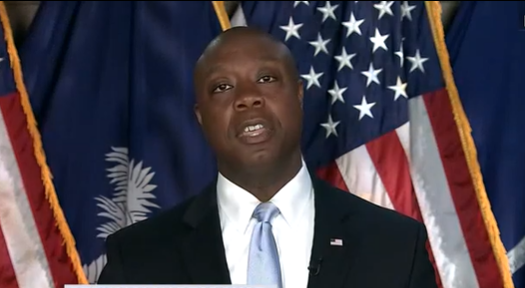

U.S. Sen. Tim Scott, who released his “Kids in Classes Act” Feb. 2, says he is troubled by the likelihood that inconsistent learning routines will cause learning challenges for students but is more distressed by the lack of civility that has ensued in the wake of the pandemic.

Editor’s note: Jonathan Butcher, senior policy analyst in the Center for Education Policy's Institute for Family, Community and Opportunity at The Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, interviewed Sen. Tim Scott from South Carolina shortly before Scott released a plan to provide students in low-income areas access to their share of Title 1 spending if an assigned school closes to in-person learning.

U.S. Sen. Tim Scott (R-SC) is not shy when talking about the grades he earned in high school. He does not hide the fact that he failed four classes as a freshman, which put his future success in doubt.

Scott can empathize, then, with the share of students in the northwest corner of his home state who are failing in school today. The share of students earning D’s and F’s tripled during the pandemic, and the media uncovered similar results around the country.

But Scott explains that students are struggling today for different reasons than he did.

“The truth is, what we’re experiencing today is very different than what I experienced; what I experienced was a failure on my part,” Scott said in his interview with me in January. “What we’re seeing today is a failure on our institutions’ part.”

As unions bicker with city mayors and district officials, as happened recently in Chicago, students and families are left with few alternatives. Scott blames teacher unions for keeping some 340,000 Chicago children from learning in person for much of January when union leaders and members told city leaders that teachers were not returning to in-person learning.

He was troubled by the likelihood that an inconsistent learning routine would set children back, but he also was concerned about union leaders’ lack of civility. In the midst of the shutdown, one union leader called Mayor Lori Lightfoot “relentlessly stupid.”

“That kind of low-level, low common denominator debating and bickering tells me that the impact on our education and the institutions that provide it is really severe,” Scott said. “The civility that is being lost among adults who say that they’re looking out for the best interest of kids, it’s undeniable — and that is as concerning to me as the failures that we’re seeing within the system.”

Federal officials have a poor record when it comes to K-12 education policy except on the rare occasions when a lawmaker tries to give parents and students more flexibility with money that has already been designated to students. Scott’s new proposal is of the latter type.

During our interview, he proposed that lawmakers provide students in low-income areas access to their share of Title I spending if an assigned school closes to in-person learning. Scott officially released his proposal on February 2, calling it the “Kids in Classes Act.”

Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) directs the largest share of federal spending on elementary and secondary students. In 2016, my colleague Lindsey Burke and I explained that such small grants using Title I spending could amount to $500-600 per student, which would allow families enough resources to find a personal tutor, education therapist, or other short-term solution while assigned schools were closed.

Such grants also could continue a child’s learning experience while parents seek long-term solutions for their student.

“I want to make sure that we give the parents as many arrows in the quiver to meet the needs and hit the target for their kids,” Scott said. He explained that he intends for education savings accounts, which allow parents to use a portion of their child’s funds from the state funding formula to purchase education products and services for their student, to become “normal.”

Scott says, “That type of normalcy is actually extraordinary.”

And so is a proposal from Washington that does not allow federal officials to intrude on local schools but helps families meet the needs of their children immediately, without waiting for unions and district officials to decide who is in charge of a school building.