Five member universities departed the Pacific-12 Conference last week, following the leads of three others. Despite boasting more NCAA national championships than any other league, the “Conference of Champions” as we knew it died. I anxiously await a modern Edward Gibbon to document the fall of this part of American life. While we naturally regret the fall of valued institutions, we have cause to fear efforts to prop up failed institutions even more.

As an Arizonan, I know many who feel an acute sadness to see the Pacific-12 go. The Pacific-12 Conference participated in cherished traditions such as the Rose Bowl and the Rose Bowl Parade. College football has slowly but steadily shifted from being a quaint but delightful regional pastime into professionalization. Many, including your author, find this unsettling. The Conference of Champions was a cherished part of life in the American West but died through partition.

We should, however, understand change as being inevitable, and stasis as dangerous. The amateur model eventually collapsed under the crushing weight of hypocrisy. Universities made hundreds of millions of dollars while enforcing “amateurism” on athletes. Professional profits for me, amateurism for thee was only going to last so long. Sure enough an (appropriate) assertion of individual rights by athletes in court set athletic departments scrambling for the resources to compensate players, accelerating a trend towards consolidation.

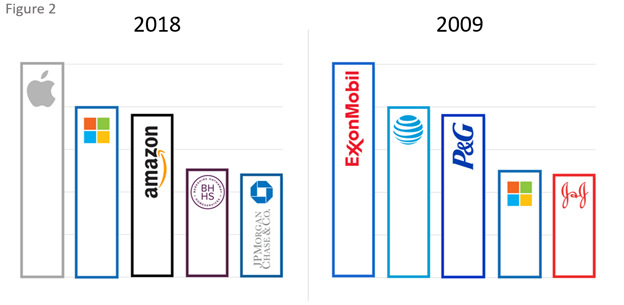

Constant change is also a feature, not a bug, of American industry. The S&P 500 is an index of large American publicly traded corporations. On average there are 22 changes in the index annually. This means that half of the companies in today’s S&P 500 index were not in the index 20 years ago. Companies drop out for a variety of reasons: bankruptcy, mergers or simple decline. Growing, upstart companies move into the index as others fall out. Even the apex companies are not immune. For instance, none of the top five S&P 500 companies from 2009 was still in the top five in 2018.

We can see the danger of stasis in America’s K-12 system. Americans regret the closing of a public school as we in the West feel about the loss of the PAC-12. If, however, we allow antiquated institutions to linger despite an established inability to deliver, we pit our sentimentality against our flourishing. The failed K-12 status quo traps teachers in dysfunctional bureaucratic systems and shortchanges students while creating an ever-growing financial burden on society.

The beneficiaries of today’s high-cost but low performing K-12 system have largely configured the K-12 system to their interests. They have effectively organized themselves for political action and fiercely resist change. They use our sentimentality to maintain stasis. The best method for managing the very real tension between our desire for freedom and progress and our desire for stability and tradition lies in voluntary associations. In K-12 this means giving teachers and families the opportunity to supply and demand schools and allowing voluntary associations to decide which thrive and which close.

We currently leave to politics the task of deciding which schools replicate and close. The PAC-12 demonstrated a regrettable level of dysfunction in the years leading to the dissolution, but it operated as a well-oiled machine in comparison to many American school districts.

An ongoing voting with feet can decide which institutions we value enough to preserve, and which should go the way of a delisted company or (alas) the Conference of Champions. While we honor tradition, eternal life is not ours to grant our institutions, and a great folly lies in attempting to grant it. We should empower families, not bureaucrats, to resolve the tension between tradition and progress.