For the past several years, the story of American homeschooling has been a narrative sorely lacking reliable numbers.

Last week, The Washington Post filled the void with the first carefully assembled nationwide look at state and local administrative data.

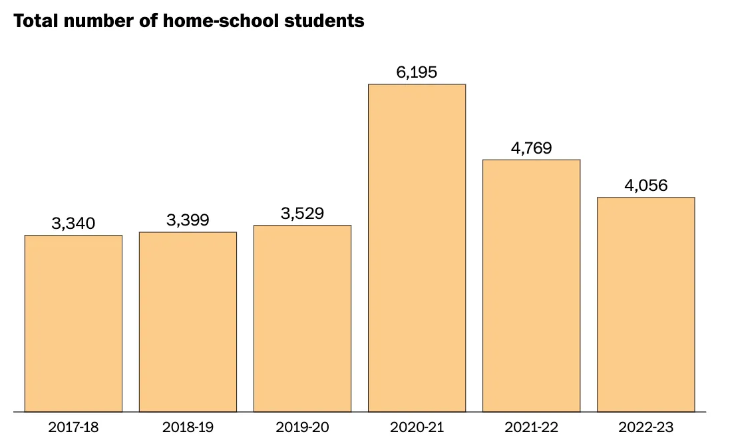

It found that in the states where comparable data exist, homeschooling is up 51% during a six-year period that includes the pandemic and years since.

That's a seismic shift in American public education, but it's still poorly understood. Here's the full picture in a nutshell:

Homeschooling jumped, dramatically, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some of that increase was sticky. Parents left schools and decided they liked it.

Some of it wasn't. Parents who tried their hand at homeschooling during the pandemic quickly returned to schools once they reopened.

There is regional variation. The trend appears stickier in parts of Florida than in, say, the DC suburb of Fairfax County, Virginia.

Homeschooling is down from its pandemic-era peak. But it's way up from the pre-pandemic status quo. And it's continuing a trend the predates the pandemic: the increase in families taking more control of their children's learning. This can take the form of homeschooling. It can also take the form of new education options that blur the lines between school and homeschool.

Up or down?

The Post caught the attention of skeptics, like writer and researcher Chad Aldeman, who himself opted to homeschool at the height of the pandemic, only to return once schools reopened. The homeschooling trends in his own county suggest hundreds of other parents made similar choices at the height of school closures.

Aldeman errs in implying that his county, a D.C. suburb where the median household income is nearly twice the national average, typifies the national trend. It doesn't.

The overall homeschooling increase in Fairfax is smaller, and the pandemic-era spike and subsequent decline more pronounced, than in the Post's multistate average.

There are several plausible reasons Fairfax stands out.

Fairfax County homeschooling numbers crashed back to Earth once schools reopened. Source: Washington Post

Compared to school systems in most of the country, Fairfax's pandemic-era school closures were notoriously long-lived and ineptly managed. This may have pushed more members of its highly educated population to take teaching into their own hands. Its high incomes also created a high opportunity cost for parents to continue homeschooling once schools reopened. The typical Fairfax parent who chose to remain out of work to support the homeschooling of their children would have foregone more money, and more potential wealth-building, than the typical American family.

Ultimately, Aldeman and the Post are both right. Homeschooling is way up from pre-pandemic levels. And it appears to be declining in many places right now. But it's still significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels, on average, and in some places, like Florida, the numbers are still going up.

Big or small?

Skeptics also pooh-pooh the magnitude of the rise of homeschooling. A 51% increase in homeschooling represents a shift from about 3% of American K-12 students to about 4.5%. Is that a big deal?

For one thing, 1.5% of American schoolchildren equals about 750,000 students. People can disagree whether a fundamental change in the learning arrangements for that many young people is a big deal.

But that number understates what's actually going on.

In Florida, two scholarship programs (the Unique Abilities scholarship and the Personalized Education Program, or PEP) allow families to pay for fully unbundled education. Combined, they're serving more than 100,000 students. Some students in the latter program may register as homeschoolers. Others don't. And students using PEP scholarships are explicitly legally distinct from homeschoolers.

In other words, many of them won't show up as homeschoolers in administrative data. However, all of them have the opportunity to engage in homeschool-like behavior. They might enroll in schools. They might not. Their parents have taken responsibility for assembling the educational program for their children. Other families have enrolled in hybrid schools, microschools or online schools. They won't show up as homeschoolers in administrative data, but they're blurring the lines between schooling and homeschooling.

Pandemic blip or permanent shift?

A useful analogy to help put the rise and decline of homeschooling in perspective is grocery delivery.

Instacart stated in 2012 with what may have seemed like a niche business. Then it suddenly exploded during the pandemic as people eschewed in-person shopping. It's since come back to earth, but the business is still far larger than before the pandemic and recently made a healthy stock market debut.

As a company, its future is uncertain, and turbulence lies ahead. But the zooming in on the trajectory of one grocery delivery company obscures a larger, more undeniable trend: online delivery is eating the retail business. Fresh meat and produce might be more resistant to this shift than, say, books or shoes. But Americans are getting more goods delivered to their doorsteps and buying less in physical stores. The trend is moving in one direction.

The same pattern applies to homeschooling or individual microschool and online learning providers. Individual options will have their ups and downs. But larger shifts are harder to ignore.

Public trust in institutions is declining. Anxious millennial parents want more transparency and communication from their schools. Remote work and flexible hours give them more opportunities to co-produce education with their children. They know each of their children is different, and they want learning experiences that accommodate these individual differences.

Homeschooling is one response to these larger shifts. Many of the distinct motivations for homeschooling captured in recent parent surveys by EdChoice boil down to trust. The No. 1 concern of homeschooling families, safety, can also be seen as a lack of trust that schools will provide children with a safe environment.

But there are obvious forces limiting the growth potential of homeschooling, strictly defined. An earlier Washington Post survey showed homeschool families typically rely on one parent, almost always the mother, remaining out of the workforce to take charge of educating their children.

At the same time, the profile of the typical homeschooler is changing. Homeschooling is becoming more diverse, as well as less conservative and traditionally religious. Many of these newer homeschoolers aren't ideologically opposed to public education. It stands to reason that if public education finds ways to earn these parents' trust and support their individual needs, it might yet find ways to keep them, much in the same way Wal-Mart and Amazon are devising ways to fend off the challenge from Instacart.

Homeschooling numbers, in other words, are best understood as leading indicators of larger shifts that public education ignores at its peril.