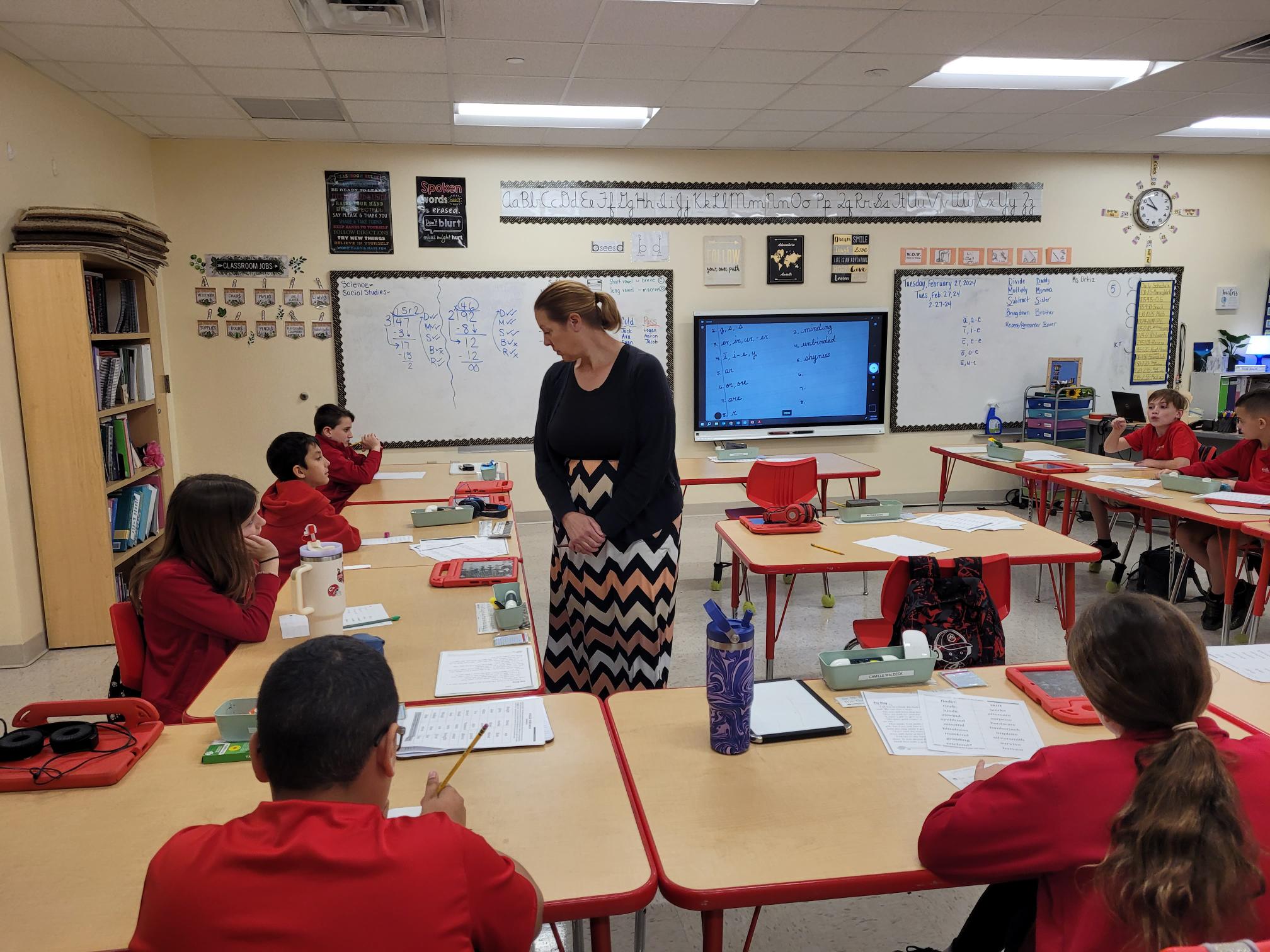

LAKELAND, Florida — The fifth graders listen intently as the teacher Alexandra Probasco slowly reads a sentence: “Tammy got in trouble for interjecting during class.”

LAKELAND, Florida — The fifth graders listen intently as the teacher Alexandra Probasco slowly reads a sentence: “Tammy got in trouble for interjecting during class.”

Their assignment: Decode the sentence, translating the sounds of the letters in the words their teacher says into writing on a page. Students tap out syllables with their fingers on the opposite arm. After repeating the sentence several times, along with a couple of gentle hints to think about the sounds in certain words, each student had successfully written out the sentence.

“Mrs. Pro,” as the students call Probasco, and the other teachers at this small private school in Lakeland use the Orton-Gillingham Approach to teach reading, writing and spelling. It relies on a multi-sensory approach and has been called the gold standard for students with dyslexia.

The Roberts Academy has used Orton-Gillingham since it opened in 2010. For a video detailing ho w the school uses the approach, go here.

Developed in the 1930s and 40s for students who had what was then called “word blindness,” Orton-Gillingham teachers use hearing, sight and movement, such as tapping out syllables. Students use phonics to decode words and memorize common spelling rules.

For example, the letter g can sound like j if it comes before an i, e or y, as in gem, giant, gym, but it says g before everything else, as in garden or glad. Those rules, along with corresponding hand signals used to teach them, can be seen in colorful classroom bulletin board displays. Roberts’s teachers call words that don’t follow the rules “heart words,” which means students must learn them by heart. They even draw tiny hearts around them to help make the point.

The approach is grounded in the “science of reading,” a term that refers to decades of research that point to effective strategies for teaching kids to read.

Parents of dyslexic students have been among the groups leading the push to use methods that systematically teach students to connect the sounds letters make to the words they see on the page. These methods are an essential component of effective reading instruction for all students, but they’re especially vital for students with dyslexia because the learning disability scrambles the connections readers make between words and sounds but can be overcome with the right support.

Private tutors trained in approaches such as Orton-Gillingham can cost $50 an hour. Many states, including Florida, passed legislation recently that bans discredited approaches and requires teachers to use phonics as the basis for reading instruction.

But the Roberts Academy has been ahead of the curve, which is a primary reason for its growth.

“We would love it if they’d build a high school,” said Cassie Ridgely, whose son, Chase, 12, started at Roberts in second grade shortly after being diagnosed with dyslexia. Before that, he had attended a private faith-based school. Though the teachers there offered extra help through a special program, he needed something more. . Now in fifth grade, Chase can read closer to grade level.

“It takes a lot of patience to work with these kids every day,” said Ridgely, who also likes that classes are limited to 12 students. ‘We have never had any issues if Chase needed extra help.”

An effective and affordable solution

Some families drive an hour and 15 minutes one way from Windermere near Orlando, so their kids can attend the school, which accepts the Florida Family Empowerment Scholarship for students with Unique Abilities.

Parents offer heartfelt testimonials about how their children no longer hate school now that they realize they can learn. One dad talked about how his daughter, who used to memorize storybooks but couldn’t read any individual words in them, started reading restaurant menus after switching to the Roberts Academy.

That confidence can be witnessed in a classroom where teacher Brittany Longbottom helps her fourth graders learn words by pronouncing them, sounding out the letters and writing them.

“Charm-er,” she says, careful to separate the syllables as uses her hand to tap them on her other arm. The students do the same and then write the word on their papers.

The next word, “termites,” is a bit trickier. After tapping to help them break down the syllables, Longbottom reminds them of the silent-e rule that governs vowel sounds of words ending in e as the students write the word. According to the rule, the e at the end of the word isn’t pronounced but gives the vowel in that syllable a long sound, or makes it say its name.

“Good job,” she says after they write the word on their papers.

Growing demand fuels expansion

Nestled on the campus of Florida Southern College campus amid buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, the private school owes its existence to Marjorie and Hal Roberts, Lakeland philanthropists who donated $3.5 million to start the school when several their grandchildren thrived at the Schenck School, a private school in metro Atlanta known as a national leader among schools that focus on students with dyslexia. They described the school as a “transitional school” that students could attend until they had acquired the skills they needed to return to regular school.

“They thought Lakeland needed a school like that,” said head of school Kim Kelley, a former public elementary school teacher who joined the Roberts faculty after her nephew enrolled in 2011. While working at Roberts, she earned her master’s and doctoral degrees in education from Florida Southern. The school enjoys a partnership with the college, which sends its teacher prep students through a rotation at the school and offers a course in Orton-Gillingham. One first-year Florida Southern student, Saylor Kirkpatrick, is a Roberts Academy graduate who plans to major in elementary education.

The Roberts Academy initially served students in second through sixth grade. It added a second building in 2020 after phasing in seventh and eighth grades in 2017.

Earlier this year, Roberts cut the ribbon on a new 22,000-square-foot two-story addition that includes a state-of-the-art mathematics and science/computer labs, a cafeteria, gym with a rock-climbing wall, a large patio area designed for outside reading, writing, and collaborative study, nine new classrooms, and additional office space. Next school year, the school will add a first grade.

Kirkpatrick was among the speakers at the dedication ceremony. “I am not saying that learning becomes easier for students with disabilities like me, but I am rather saying having the right people working with your children can and will make it possible,” she said.

The Roberts’s have not limited their generosity to their former Florida hometown. A second school with the same name is slated to open in August on the campus of Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. Like the original school, the new campus will limit class sizes to 12 students. It will partner with the university’s college of education.

“Having experienced our grandchildren’s early struggles and their later achievements, and those of hundreds of children at the Academy in Lakeland, we feel compelled to help others accomplish the same success,” Hal Roberts said when Mercer officials announced plan for the new school. “We have experienced parents in tears of frustration and been with them two weeks later as they were thrilled over their child’s immediate acceptance by children with the same challenges and their early progress in school.”