Nearly 24,000 Alaska homeschooled students who use a unique state program to customize their education would have to scramble for alternatives under a trial court ruling that struck down a 10-year-old law.

In a sweeping ruling on Friday evening, Anchorage Superior Court Judge Adolf Zeman sided with the teachers union-backed plaintiffs in a lawsuit challenging a 2014 law that allows the parents of students enrolled in correspondence courses to spend their share of state money, called an allotment, on “nonsectarian services offered by a public, private, or religious organization.”

The unique program gives rural families in the nation’s largest and most remote state the ability to use state money to procure diverse learning options for their children.

But Zeman ruled that allowing families to purchase curriculum or courses from private organizations violates the state constitution, and fatally undermines the program.

“This court finds that there is no workable way to construe the statutes to allow only constitutional spending,” Zeman wrote in a 33-page order, concluding that the relevant laws “must be struck down in their entirety.”

“This court finds that there is no workable way to construe the statutes to allow only constitutional spending,” Zeman wrote in a 33-page order, concluding that the relevant laws “must be struck down in their entirety.”

He added, “If the legislature believes these expenditures are necessary—then it is up to them to craft constitutional legislation to serve that purpose—that is not this Court’s role.”

The central issue in the case, which parents of four public school students filed against the state, was Alaska’s so-called Blaine Amendment, which says, in part, “no money shall be paid from public funds for the direct benefit of any religious or other private educational institution.”

Attorneys for the Institute for Justice, which intervened on behalf of three families benefiting from the program, argued the allotment program was constitutional because parents could choose to spend the money on a variety of options, including public programs. That feature distinguished the allotment program from a prior case that struck down a tuition grant program available only to students attending private colleges.

However, Zeman said in his order that an examination of the minutes of the Alaska Constitutional Convention showed that delegates chose the language “public funds” instead of “state funds” to clarify that money directed by parents was still benefiting private education despite passing through “many hands.”

Zeman added that he did not find arguments that the legislature merely gave parents options and did not direct the money to private institutions “persuasive.” He wrote that he sees “no difference” between parents receiving the allotments and college students receiving tuition grants and then paying a private university.

He pointed out that the parents intervening in the case “explicitly acknowledge” spending their allotments on private schools.

“They note that without the allotment money, they could not send their children to private school, or that doing so would create a significant financial burden,” he wrote. “Parents have the right to determine how their children are educated. However, the framers of our constitution and the subsequent case law clearly indicate that public funds are not to be spent on private educations.”

Zeman also wrote that then-state Sen. Mike Dunleavy, who sponsored the legislation in 2013, knew a constitutional change was needed to withstand a court challenge. Dunleavy, now Alaska’s governor, proposed a constitutional amendment that died in committee even though the law passed a year later.

The legislation expanded a unique program established in 1939 to ensure students in the most remote areas of Alaska had access to education. Known as correspondence programs, they allowed public schools to send assignments by mail or float plane to students, who would complete course packets and return them for grades. When the homeschooling movement began in the late 1970s and ‘’80s, correspondence programs became popular with parents who used them as part of their children’s education plans. During the coronavirus pandemic, demand increased as parents sought more educational options. The program allows each student about $4,500.

Controversy erupted in 2022 when the wife of Alaska Attorney General Treg Taylor published a blog post encouraging families to use their allotments for private school tuition. The plaintiffs sued seven months later.

The ruling stunned Alaska lawmakers, who hoped the judge would delay its implementation until summer so participating students could finish the school year.

On Saturday, Dunleavy posted on the social media platform X that the ruling was “flawed” and that the state would push for a speedy resolution by the state Supreme Court, and to block the judge’s order from taking effect while the legal issues were sorted out.

“With 24,000 students enrolled in these programs to say this would be disruptive would be an understatement,” he wrote.

The Institute for Justice called the decision “incredibly disappointing” and said it plans to appeal on behalf of the families it represents. The lead attorney in the case for IJ told NextSteps last year that such a broad interpretation of Alaska’s constitution would put the state “in direct conflict” with rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court that gave parents the right to direct the education of their children.

“In its opinion, the court ruled that a program that benefits families throughout the state violates the Alaska Constitution,” attorney Kirby Thomas West said. “The court completely ignored our strong claims that this incorrect reading of the Alaska Constitution puts it at odds with the protections of the United States Constitution.”

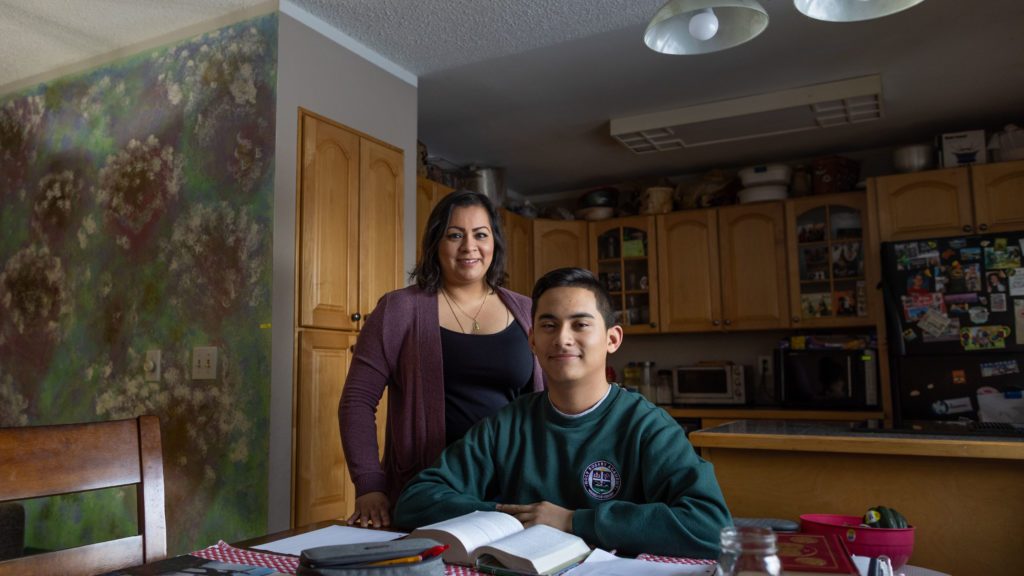

Andrea Moceri, one of the parents working with IJ to defend the program vowed to continue the battle.

“This program is vitally important to my family, and so many others across the state,” Morceri said. “I’m disappointed by the court’s decision, but we’re not giving up. We will appeal and continue to fight to ensure that my son, and every other Alaskan child, has access to the education that best fits his or her unique needs.”

Andrea uses the program to send her son to Holy Rosary Academy in Anchorage, where he has excelled academically. But without the program, it would be economically impossible for her to send her son to the school at which he has found success.