Today we are debuting an interruption of our normal roundup of Florida education news with a new weekly scan of events across the country.

It will land in your inboxes and Next Steps on Thursdays.

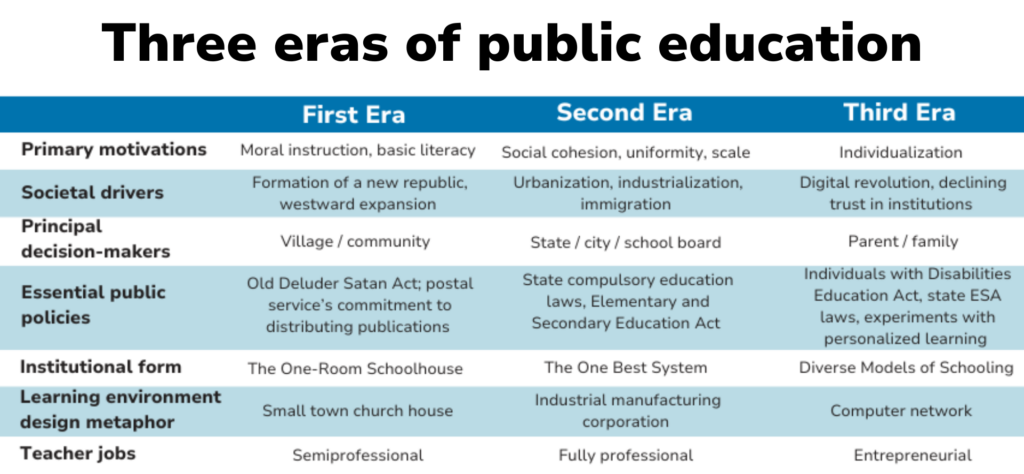

Over the holiday break, Doug Tuthill, Step Up’s chief vision officer, gave us the lens we will use to read the national news: U.S. public education is shifting from its second era to its third.

We’re living amid the biggest upheaval in education since the Industrial Revolution, with all the turbulence and opportunity that implies.

To help set the tone for the new year, we’re looking at 10 key trends we expect will shape education news in 2025.

Please drop me a line and let me know what you think.

The great blurring of the lines

In the new era of public education, parents take on a greater role directing their children’s learning.

Many of these parents seek learning options outside the four walls of school, like tutors or part-time and hybrid schools. They may purchase some structured curriculum and improvise other learning experiences themselves. They may sign up for some classes online and enlist the help of learning centers that provide in-person support aligned with their schedules.

Homeschoolers pioneered this approach to parent-directed education for four decades. A host of newcomers are joining them, and many don’t qualify as homeschoolers in strict legal terms.

This year in Florida, more than 100,000 students are using state scholarships that don’t require full-time enrollment in a conventional school.

Their families are finding and creating new types of educational service providers that stretch conventional definitional boundaries between schooling and homeschooling, in-person and online, full time and part time. As these options proliferate, the tidy categories that define what counts as a school or who counts as a homeschooler keep getting messier.

The explosion of education entrepreneurship

Some of the most passionate and creative teachers in existing schools are also some of the most frustrated. Across the country, many of them are breaking free, creating new schools or line-blurring learning options.

These educators take profound risks, leaving behind a stable paycheck, health benefits, and all the support a school system provides. They learn on the fly about everything from managing cash flow to liability insurance to zoning approvals for educational facilities.

Each entrepreneur who creates a new learning option lowers the cost of courage for others who might follow. Informal peer networks and formal support institutions are emerging to straighten the paths for new educational ventures.

Students access public schools on their terms

One under-the-radar policy trend keeps gaining momentum: States are doing away with geographic school assignments, making every public school available to all students, regardless of where they live. And from Delaware to Wisconsin, families are taking advantage.

The steady progress of open enrollment isn’t the only shift allowing more families to access public schools on their terms. Families are enrolling students in public schools part time, signing up for courses and extracurricular activities they need while customizing other parts of their child’s education from other sources.

In Florida, half a dozen school districts offer classes and other activities to students who use state scholarships, and more districts and charter schools are poised to follow suit.

Below the surface, this is a marked shift for public school systems, which are built to serve students who are assigned to the school they attend based on where they live. This shift is simpler to call for than to execute. Configuring student data systems, safe building access, transportation networks and countless other facets of their operations to support students who enroll by choice or select classes or activities a la carte requires public schools to develop new organizational muscles.

The clash of constitutions

Lisa Buie has ably chronicled a conflict that flares across the country as states embrace the third era of public education, enacting policies that give more families the power to direct public education funding.

These policies often clash with provisions in state constitutions that were enacted during the second era, which call for “thorough” or “uniform” public school systems and which, in some cases, bar public funding from flowing to private institutions.

This is the theme of many school choice-related legal battles at the state level: State leaders want to give parents power to direct public education funding, but these efforts run afoul of decades-old restrictions on how public education funding can flow.

Challenges to test-based school accountability

On November’s ballot, Massachusetts voters approved a referendum doing away with standardized high school exit exams. It was the latest indicator of a broader shift that has been building for a decade.

In 2015, Congress eased federal requirements for states to hold public schools accountable for their performance. States have faced growing pressure to back away from accountability measures that helped drive school improvement and ensure all students were held to high expectations.

Leaders in some states, like Virginia, are resisting that pressure. At the same time, those committed to rigor and high expectations are adjusting to the rise of new forms of accountability—including direct accountability to families who choose where their children learn.

States and school systems build infrastructure for a new era

Texas made national headlines assembling a state-owned curriculum, Bluebonnet Learning.

But those headlines tended to fixate on one of the least interesting aspects of the curriculum: the fact that a small number of lessons include some material from the Bible.

The curriculum is intended to solve a problem classroom teachers face all over the country: Their schools often lack a formal curriculum aligned to their students’ needs, so they find themselves cobbling together assignments and lesson plans, often casting about for ideas online. This consumes tons of teachers’ time and hurts the quality of instruction.

Bluebonnet’s architects and its critics may both be missing its transformational potential outside the school system. Many parent educators and microschool founders face the same basic challenge as teachers scrambling to create lessons from scratch. They often find they’re on their own to identify, develop and deploy curriculum.

A resource like Bluebonnet gives them a starting point. Any teacher (or parent, or other adult in a teacherlike role) can download Bluebonnet resources. They can use the lessons they like, modify them at will, and discard the rest.

Freely available curriculum resources that have already been vetted through a public process ought to be a boon to do-it-yourself educators. And they represent a larger trend: More states, intentionally or, in some cases, unintentionally, are creating resources that promise to help more parents and educators flourish outside the confines of a traditional education system.

Creating open curriculum resources is one way to do that. There are others, such as supporting organizations that help families choose education options and creating online information portals for parents.

Demographic and budget pressures mount

Across the country, schools are losing enrollment as the number of school-age children shrinks. This is bringing political and financial turmoil, like the chaos engulfing Chicago, where a mayor following a teachers union playbook is attempting to muscle the school superintendent out of a job.

Behind the power struggle is a nine-figure budget gap and a district that hired thousands of new staff while enrollment fell by a fifth and nearly a third of all schools are less than half full.

It's an extreme case, but a bellwether for enrollment and financial trends in large school districts across the country.

Against that backdrop, Florida appears relatively well-off. It’s one of just 10 states where K-12 enrollment is projected to grow through 2031, but the growth is likely to be uneven, with some districts looking for creative ways to absorb growth and others seeing student populations decline. Solutions that allow public schools to grow flexibly, attract new students, keep existing students from leaving, or make creative use of under-used buildings will likely be in high demand.

A new approach to federal leadership

President-elect Donald Trump campaigned on eliminating the U.S. Department of Education. His new administration could play an assertive role in shaping education while, at the same time, reducing formal federal bureaucratic oversight of the nation’s schools.

Two key areas to watch:

One potential early indicator: Outgoing Education Secretary Miguel Cardona had little to say about American students’ dismal showing on international assessment results released in this fall. New national assessment results are scheduled to be released on Jan. 29, just days after Trump gets sworn in. Will the results show more declines, or a turnaround? And how will the new administration react?

The domestication of AI

From tutors to would-be teaching assistants, most of the heavily hyped educational applications for artificial intelligence have one thing in common: they don’t really challenge the status quo in schools.

MIT’s Justin Reich has observed that the education system tends to “domesticate” new technologies, rather than be transformed by them. Most schools are connected to the internet, but the basic “grammar of schooling” (students are grouped by age, a few dozen to a classroom, led by a single instructor) looks about the same as it did when that term was coined in the ‘90s.

There’s a simple reason for this: the makers of new education-related AI tools need customers for their products, and by and large, those customers tend to be existing schools and districts, which control most of the purchasing power in public education.

Tools like Synthesis Tutor, which use AI to power learning experiences that look vastly different from a conventional classroom, sit at the margins. Parents might choose to pay for them, if they can afford to, and offer them to their children instead of, or in addition to, conventional schooling.

The question is how this might change as more families gain the power to direct education funding on behalf of their children. The answer may depend on whether new value networks emerge to support them.

The failure of well-intended, one-size-fits-all policies

San Francisco drew criticism for a policy that barred academically advanced eighth graders taking algebra. Critics of the move, eventually reversed, pointed to data showing it reduced advanced course-taking and blocked high schoolers from pursuing college credits in a misguided attempt to promote fairness.

A Minnesota policy repeated the same mistake in reverse, accelerating all eight graders into algebra courses. This, too, wound up hurting many students it was intended to help.

A challenge for educators in the third era will be setting high academic expectations for all students, and, where necessary, pushing them to perform and allowing the most advanced students to soar, while also respecting the individual needs and agency of each student.

What trends are you watching? What’s missing? Please drop me a line and let me know what you think.