Sunday afternoon, while most Americans settled in for the Super Bowl, Open AI’s Sam Altman published a blog post that made some extraordinary claims:

In a decade, perhaps everyone on earth will be capable of accomplishing more than the most impactful person can today.

Predictions like this have many people wondering how education will change as artificial intelligence allows machines take on a growing number of tasks previously reserved for humans.

It’s tempting to view the potential of new technologies through the old paradigm of public education and its factory-like assumptions. Right now, we bring students into school buildings. Add curriculum. Through the labor of teachers, learning occurs. Could AI automate some of that labor?

A more helpful frame may be something like this: In the third era of public education, artificial intelligence will give educators and families new tools to help students learn. These tools are already showing up in three ways.

First, existing schools are using AI tools to meet specific needs. When they are thoughtfully chosen and artfully deployed, they can be help students in ways that weren’t previously feasible, as school districts in Louisiana have learned:

Zakiyatou “Zaki” Arouna is 10 years old and attends Phoebe Hearst Elementary in Metairie. We visited Arouna and her fellow classmates as they were developing their reading skills with the help of a tutor named Amira. It is not a typical tutor. It’s powered by artificial intelligence, and Arouna is all-in with AI.

“I see it as something that could really help you, and it can help you improve your reading,” Arouna said. “When I first started, I could barely read. Because when I first came to the country, I didn’t know how to speak English.”

Second, new schools, like Alpha School, use AI-powered instruction to radically rethink how they use time and teachers:

Students spend their mornings engaging in a highly personalized curriculum in the core subjects: math, reading, science, and social science. The AI-driven system assesses their knowledge in real time, identifying gaps and ensuring they achieve mastery before progressing. This mastery-based approach allows students to advance far beyond grade level if they are ready or to fill in foundational gaps before proceeding.

Teachers, now called “guides,” do not lecture or grade assignments in these core courses. Instead, they act as motivators and mentors, helping students remain engaged and on track. In the afternoons, students take part in workshops and collaborative projects centered on public speaking, leadership, entrepreneurship, and other practical skills. Afternoons can also include skill-building workshops, debates, coding projects, and creative endeavors, activities often squeezed out of the traditional school schedule. Older students can use this time to explore internships, research opportunities, or other substantive outside endeavors impossible to do within the confines of a traditional school. These activities ensure that learning is not solely about acquiring knowledge, actively or passively, but about exploring it and putting it to use while building confidence, enhancing communication skills, and honing problem-solving abilities.

Third, a growing number of families are using tools like Synthesis Tutor to meet specific instructional needs for their children outside the conventional structures of school. Some also look to learning centers like KaiPod for in-person connections, group activities, and adults who can get to know their kids and keep them motivated.

None of these concepts is strictly new. Long before the current AI hype cycle, the Kahn Lab School and charter school networks like Rocketship and Summit Public Schools used technology to reshape traditional school schedules and routines. These efforts saw mixed results and imparted some hard lessons about the limits of technology’s power to transform schools. A prior generation of experiments with adaptive learning software also showed it tends to be less helpful for less-motivated and lower-achieving students.

The question, then, is not what “all students will” or “all teachers must” do in the age of AI. It’s how to help families and educators take full advantage of a new generation of tools while learning from past misadventures with education technology.

In Brief

Knowledge workers who use AI on the job may see their critical thinking skills diminish.

Presumptive Education Secretary Linda MacMahon argued during her Thursday confirmation hearing that many key functions of the U.S. Department of Education, from civil rights enforcement to directing the flow of federal funding, could be better performed by other entities. One of her predecessors, Betsy DeVos, agrees, arguing the department “has failed at its mission and no longer needs to exist.”

Here’s a nuanced look at efforts to hit “pause” on federal education research funding.

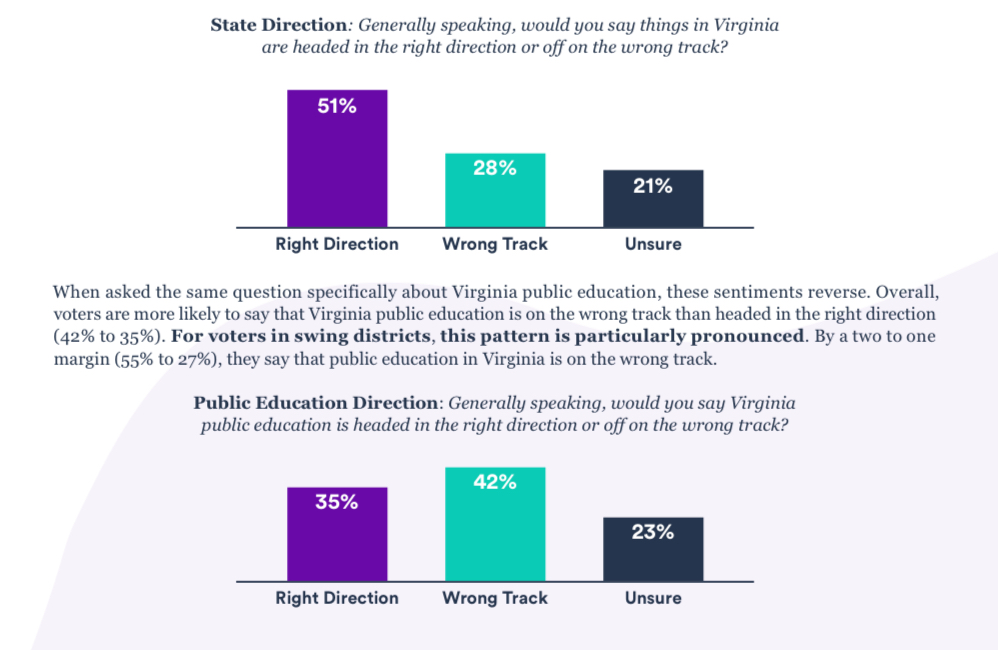

Virginia has recently earned a reputation as a bellwether of public opinion on education. A new survey finds Virginians prioritze education reform over funding increases, want more learning options for their children, and are less sanguine about public education in their state than the direction of their state as a whole.

Source: 50CAN

A growing, but still-nascent, body of research suggests a curriculum that systematically builds students’ knowledge might lead to better outcomes.

These 100 school districts managed to improve student test scores while results were slipping nationally.

Some states raised achievement among students with disabilities amid largely dismal national assessment results.

Preschools, with their lack of substitute teachers, are especially vulnerable to staff shortages.

Debates about testing in education raise a fundamental question: Who are the results for? For policymakers, to help make decisions about schools? Or for parents, who need an objective measure of how their kids are doing? On the latter count, rampant grade inflation suggests the current system is failing. The Free Press highlights a student who graduated with a 3.4 GPA despite struggling to read.

Let me know how I’m doing, objectively or otherwise.