Good Morning, and welcome to our weekly roundup of education news from around the country.

The word of the week is “abundance.”

That’s the title of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book making the media rounds.

The two authors challenge their friends on the left side of the political aisle to take a hard look at the technology bottlenecks and bureaucratic red tape that have limited access to housing, medicine, and infrastructure.

So far, few have extended this line of thinking to K-12 education. What would an education abundance agenda look like?

A few starting points:

A few years ago, when the Kansas Legislature was debating an open enrollment law, leaders in some of the state’s most exclusive school districts fretted they’d be overrun with transfer requests from less luxe locales.

These leaders said the quiet part out loud: their public schools were offering select families an exclusive privilege that could only be accessed through the real estate market.

They also turned out to be wrong.

Reason reports that once the law took efffect, thanks in part to a shrinking population of K-12 students, the number of open enrollment applications was tiny compared to the numbers of empty spots in those districts’ schools.

Allowing any student to fill any open spot in a public school is a simple way to expand access to learning opportunities, and give well-regarded schools a new way to keep classrooms full and revenue flowing as student populations decline.

2. Encourage the entrepreneurs.

Schools are filled with teachers who feel their passion and creativity are stifled.

They are also not filled with teachers who left the profession because it’s far less flexible — and offers fewer opportunities for career growth or collaboration — than most other jobs that are considered knowledge work.”

One way to treat teachers like the knowledge workers they are is to encourage a path available to knowledge workers in other professions: Go into private practice. Start your own school or “indie” education solution.

This is becoming more common, but it’s still a less-traveled path, for example, on the campuses of colleges of education, which tend to focus on producing staff for school districts.

Many educators are not well-versed in business, or know where to get started as an entrepreneur.

Fellowship programs can help teachers overcome these barriers, giving them time, training and support to succeed running their own school or education startup — and, in the process, build networks that show others that this is a real path for an education career.

Lowering the cost of courage for education entrepreneurs will make their efforts more common, and their fruits more abundant.

3. Reduce barriers to new school creation.

Teachers who do try to start their own things often get tangled in red tape.

They run afoul of the same rigid building rules, fire codes, and zoning restrictions that fuel housing scarcity — and often have little to do with the actual safety of a structure.

Some states, including Florida, have begun paring back local rules that restrict educators’ flexibility but do nothing to ensure safe learning environments. This has allowed more churches, for example, to welcome teachers into buildings that would otherwise sit vacant throughout the week. But barriers remain.

4. Embrace options beyond schools.

Some of the best options for education entrepreneurs may not be schools. They may be tutoring centers that offer one-off courses or intensive support to students with specific needs or interests. They may be subject matter specialists like Eye of a Scientist.

Too often, these options are overlooked, even by school choice advocates, who push for policies that open doors to private schools but ignore other opportunities that might meet real needs of students or create flexible job opportunities for educators who, for whatever reason, do not conform to a traditional classroom role.

Much like housing will never be abundant if every neighborhood must consist solely of single-family dwellings on large lots, education will never be abundant if educator jobs and publicly funded learning opportunities are confined to conventional schools.

Bottom line: The key to making education opportunities abundant is to challenge assumptions that undergird a system designed to make them scarce.

In Brief

Opposition to high-performing charter schools by senior Massachusetts officials is scarcity thinking at its finest.

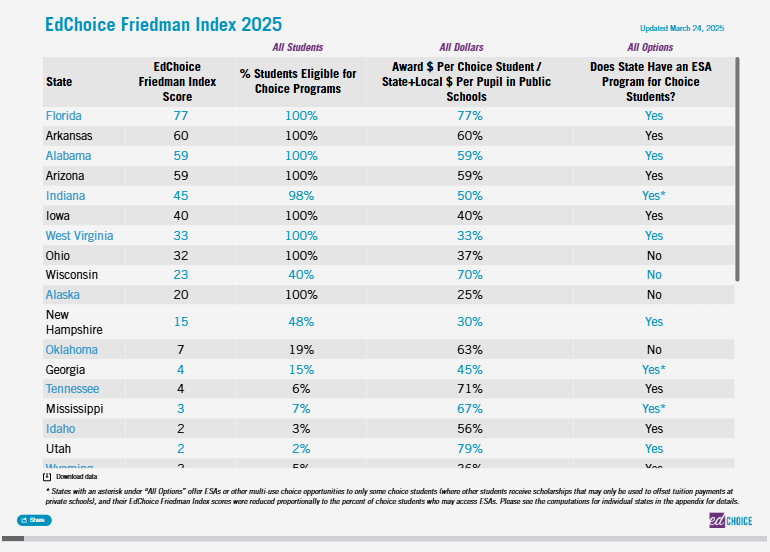

Milton Friedman famously declared in 1955 that families would be far better allocators of public education funding than governments. His beneficiaries at Ed Choice have released the Friedman Index, detailing which states come closest to the ideal of parent-directed education funding. Florida lands on top.

Iowa wants to bundle federal funds together into block grants. Allowing families to direct federal block grants through education savings accounts could be a boon to rural areas.

The lack of urgency to address pandemic learning loss may be due to flawed mental models.

When my exercise routine gets disrupted by an injury or a busy stretch at work, my conditioning quickly deteriorates. When I’m able to return to the gym, the first few workouts are a grind. But if I stick it out and resume my routine, I find that I’m back to my baseline (48-year-old) fitness level within a few weeks.

I worry many people think recovery from educational disruptions works much the same way—that if we just get kids back into classrooms and learning under normal conditions, they’ll get back on track in short order.

…

A better metaphor for learning loss is saving for retirement. If a household emergency forces me to skip a planned deposit, the shortfall in my savings account will persist until I make up for that missed payment. In fact, that shortfall will grow over time due to the foregone opportunity to earn interest on my savings.

The savings metaphor is more realistic because it incorporates a bedrock principle of the science of learning and development known as the “Matthew Effect”—an allusion to the biblical book’s teaching that the rich tend to get richer while the poor get poorer.

Schools around the country are banning cellphones to limit distractions. But what if the computers students use to complete assignments are just as harmful? Michael Bloomberg is among those raising the alarm.

A policymaker’s guide to current issues surrounding education savings accounts (ESAs).

A look at parent feedback on Arizona’s ESA program.

Parent Corner

Let's close out this week's installment with wisdom from Maria Montessori:

[Montessori] noticed that kids in the first stage of development (ages 0-6) learn by imitating their peers and the adults in their sphere. She called this phase “the absorbent mind” because her students seemed to soak up knowledge like a sponge.

In her own words:

“The child is sensitive and impressionable to such a degree that the adult ought to monitor everything he says and does, for everything is literally engraved in the child’s mind.”

This might sound a little intimidating — if our kids are watching our every move, that puts a lot of pressure on our behavior.

But this doesn’t mean we have to be perfect. It just means that we can use modeling to our advantage.