Happy Friday, and welcome to our weekly roundup of education news around the country.

The Wall Street Journal published a deep dive on AI cheating in schools — and futile attempts to stop it.

Four key points:

1. AI cheating appears to be widespread among middle, high school and college students.

Of students who reported using AI, nearly 40% of those in middle and high schools said they employed it without teachers’ permission to complete assignments, according to a survey last year by Impact Research. Among college students who use AI, the figure was nearly half. An internal analysis published by OpenAI said ChatGPT was frequently used by college students to help write papers

Students, operating on screens outside adult supervision, are left to decide whether to use or resist AI tools that can clandestinely deliver top grades. Age restrictions set by AI companies are easily circumvented.

2. In the cat-and-mouse game between students using AI and efforts to catch them, students stay one step ahead.

Reporters tested a tool created by a startup called Pangram Labs, which purports to offer the most accurate AI detection on the market.

In a Journal experiment, ChatGPT generated a ninth-grade essay on the themes of William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies.” The essay was reviewed by Pangram Labs’ detection software, which identified the writing as almost certainly AI-generated.

The essay was then fed into HumanizeAI.pro, an app that boasts it can “transform your AI-generated content into natural, human-like text.” Pangram Labs was less sure about this version. In one instance, the program said there might be some AI writing involved. On a later try with the same text, it declared the essay “fully human-written.”

Pangram Labs is working to “defeat the humanizers,” Spero said.

3. Relying on AI undermines the development of vital thinking and writing skills.

As University of Virginia cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham says in the article: "Writing requires a type of thinking that other types of exercises don't. Writing prompts you to explain more carefully if you're explaining, argue more completely if you're arguing."

There is solid evidence that using AI tools can lead to deskilling. When people outsource thinking or communication to AI tools, their own abilities weaken.

4. Teachers, and AI companies, are advocating for a better way.

The Journal found some teachers and college professors are trying new strategies, like having students write essays about interviews they’ve conducted or personal experiences that lie beyond the reach of AI tools (for now).

And Leah Belsky, OpenAI’s vice president of education, is quoted: “Educators who incorporate AI into their teaching and assignments can successfully shift it from a tool students use without disclosure to a fully integrated, guided part of their learning process.”

So what?

Schools seem on course to treat AI the same way they treated earlier technologies, like calculators or online encyclopedias, that enabled new student shortcuts.

Some will continue to play the cat-and-mouse game, attempting to restrict its use. Others will embrace Belsky's recommendation: Don’t fight it. Domesticate it. Find ways to incorporate new tools into existing school routines.

Both approaches sidestep more fundamental questions. What kind of learning experiences will help students develop a meaningful appreciation for the value of reading and writing in an era when anyone can conjure a cogent 2,000-word analysis of weather motifs in The Great Gatsby with a single-sentence prompt — and then use a “humanizer” to evade detection?

The answer to that question may look nothing like a traditional high school English class. Taking that possibility seriously may lead to radically different approaches to what we now call school.

In Brief

A new executive order from President Trump calls for winding down the U.S. Department of Education:

The Secretary of Education shall, to the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law, take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education and return authority over education to the States and local communities while ensuring the effective and uninterrupted delivery of services, programs, and benefits on which Americans rely.

Reason underlines the cost of top-down education governance led by the federal government.

In 1960, teachers comprised 64.8 percent of public education employees. By 1980, that share had fallen to 52.4 percent, and by 2022, it hit an all-time low of 47.5 percent. More education dollars are funding more bureaucrats, underscoring a failure of top-down governance. By and large, these expensive administrators and compliance officers are not improving student outcomes.

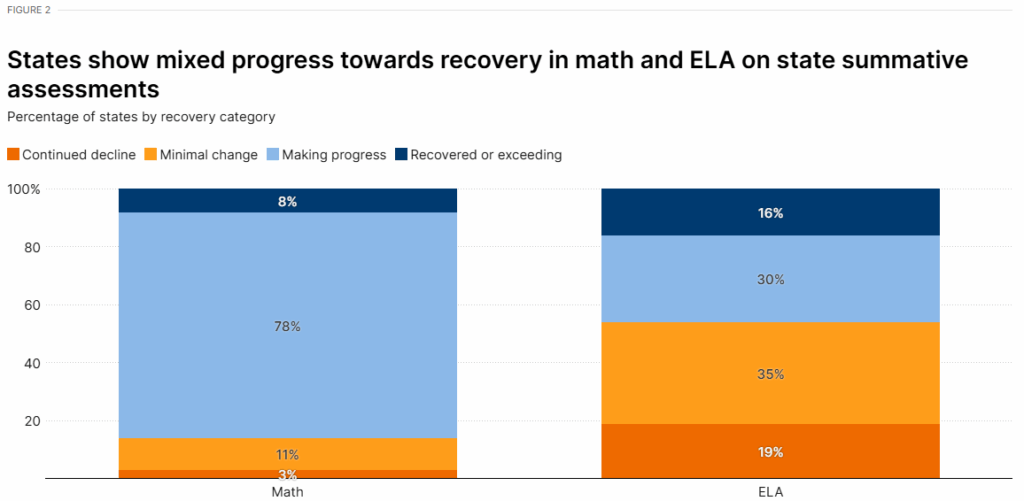

At current rates of recovery, it will take seven years for students to return to pre-pandemic levels of math achievement, a new analysis published by Brookings finds. In English, students in much of the country are still trending in the wrong direction.

A new synthesis looks at how and why schools struggled to respond to the pandemic.

A new working paper shows the introduction of broadband internet helps make the rich richer (high-performing students accelerate their learning) and the poor poorer (low performers find more distractions).

The RAND Corporation published a national review of microschools. Key points:

A new analysis finds military families are nearly twice as likely as civilians to homeschool their children.

As competition grows, “public school supporters … had better offer something new and better to the families they want to keep.”

A new response to grade inflation: Make every student (or dozens of them) a valedictorian.