While 1958 Edsels boasted multiple advanced features, the launch of the model line became symbolic of commercial failure; introduced in a recession that catastrophically affected sales of medium-priced cars, Edsels were considered overhyped, unattractive and of lower quality.

The central problem in American K-12 education, as John Chubb and Terry Moe instructed us years ago in their book, “Politics, Markets, and America’s Schools,” is politics.

In most human endeavors, we make more of what people want. If people want less of something, they stop purchasing it, quickly sending a signal to producers to make less of it.

Americans are fairly unsentimental about producers who ignore their instructions.

Henry Ford once said his customers could have one of his cars in any color they like, as long as it was black. Ford apparently imagined himself operating in a market without viable competitors, but the American public collectively disabused him of this notion by purchasing other vehicles. The Ford Motor Company lost its status as a market leader and was forced to retool its efforts/attitudes in order to survive.

Now imagine if the American automobile industry functioned like the American K-12 system. In this scenario, states draw car purchase boundaries around car manufacturing plants. Residents within this boundary pay taxes to their local plant, which is overseen in theory by an elected board. In practice, these elections are low-profile, non-partisan and often attract 10% or fewer of eligible voters. The United Autoworkers find it relatively easy to influence these elections.

Imagine a world in which the Ford Motor Company was able to utilize politics to keep making Edsels and Model Ts and Model As for decades on end.

Tiebout choice still exists, however.

If you want a car other than an Edsel, that’s no problem; you can move to a Corvette zone if you like. Yes, real estate is pricier in the Corvette zone, but your friends and neighbors intimate to you that you get what you pay for, and it’s for the children.

You also can buy a vehicle from an independent car company, but you must pay your Edsel taxes regardless, placing such vehicles out of the financial reach of most Americans.

Run this story forward a few decades. Wealthy families have long since departed from the Edsel districts and their like, having paid a real estate premium for fancy districts. The car districts continually claim they need more money to produce better cars, and taxpayers continuously provide it.

They really want a good car, and it is difficult to imagine a different system. Academic improvement generally happens at a rate nothing like the increase in spending.

Highly segregated by income and race, the public car system and the now very politically powerful interests with a stake in the status-quo become quite adept at opposing and/or undermining efforts to improve productivity in the industry. The system stands rigged in favor of the wealthy and in favor those who make Edsels; Edsels today, Edsels tomorrow, Edsels forever.

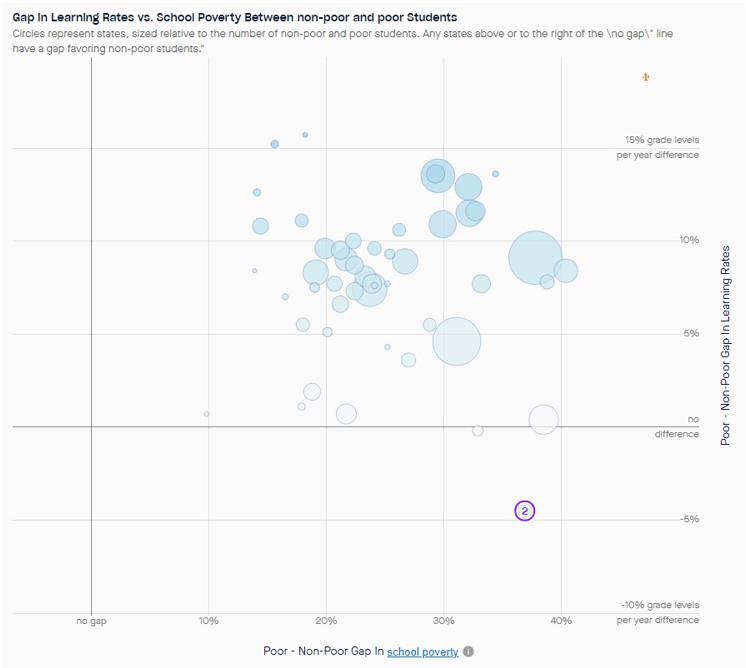

Just in case you suspect embellishment, let’s take a look at just how rigged the K-12 system is against the poor. Data from the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University will do the trick.

This chart will take some decipherment, but it is worth it, so stick with me.

This chart will take some decipherment, but it is worth it, so stick with me.

Every dot is a state. The chart shows the differences in academic growth between non-poor and poor students. Every state above the horizontal “no difference” line has a faster rate of academic growth for middle and high-income students than low-income students. Yes, it is almost everywhere.

Way at the top right, marked “1,” is the District of Columbia with the largest gap in favor of the non-poor and rich. The District of Columbia, after turning a large portion of the education of low-income D.C. students to charter schools, managed to get the academic growth rate for poor students to the national average.

Low-income students in D.C. need a faster rate than average if they are to close achievement gaps, but one suspects matters were even worse in decades past.

May the odds be ever in your favor, rich D.C. kids!

Non-poor D.C. students, meanwhile, learn at a rate 18.5% faster than the national average. Buying into that Telsa, sorry, Georgetown attendance zone will cost you a fortune, but it runs like a charm for your little darling and will take him where he wants to go.

District of Columbia Public Schools have become remarkably adept at one thing: serving the academic needs of the wealthy. The poor, not so much.

Returning to the chart, a small number of states are near the horizontal “no difference” line. None of them, however, have an impressive rate of academic growth for either non-poor or poor students.

The lone outlier, marked “2,” has a fast rate of academic growth for non-poor students and an even faster one for poor students. The learning rate for non-poor students is 11.4% higher than the national average. The learning rate for poor students, however, is 17.4% above the national average, so there was gap-closing happening in this state in the period covered (2007-2018).

Arizona, which spends perhaps one-third of the per-pupil amount spent in D.C., is state 2 on the chart. Arizona has the largest state charter school sector (around 21% of students statewide); an unusually active system of open-enrollment between district schools (about one-third of Phoenix-area students attend a non-zoned district school); and private choice programs. When the Education Freedom Index was updated after two decades, Arizona ranked first for choice in both studies.

This did not happen overnight.

The Stanford Educational Opportunity Project data does not show that Arizona students had high rates of proficiency during this period, rather that students learned more than those in any other state per year. An “Edsel district” in Arizona faces real consequences for dissatisfied families, who can move to other districts, to charters, or to a still limited but nevertheless meaningful extent to private schools with financial assistance.

School districts still educate a large majority of students, but they also are the most active choice players. Districts still have low turnout, the United Auto Workers still lobby for more money, but from an academic growth standpoint, they largely stopped making Edsels before the pandemic.

Florida, Indiana and West Virginia all look poised to make major choice advancements this year. The key to a virtuous cycle of improvement in my view will be getting the Corvette districts the right incentives to lower the drawbridges to let Edsel district kids past their moats and into their schools.

When they do, you just might see those districts produce something better than an Edsel.