Editor’s note: redefinED is supporting National Autism Awareness Month each Saturday in April by reposting articles from our archives that celebrate those who champion the educational rights of children with autism. Today’s post, which originally appeared in March 2018, features a couple whose desire to help their son led them to open an education center for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

By Livi Stanford

Michelle Dunham was troubled as she watched her son, Nick, struggle in school.

He had autism and was grouped in a classroom with children with different learning disabilities at a public school.

Dunham described her son as a gentle giant who hovers around 6’3. But he’s also non-verbal. She felt he needed one-on-one support to succeed academically. She didn’t fault his teachers, who were doing all they could to help. But to thrive, Dunham said, he needed an intensive learning environment.

“They had no resources to support him,” she said.

She talked things over with fellow parents. They encouraged her to start a school of her own.

Dunham and her husband opened the Jacksonville School for Autism in 2005, as a nonprofit K-12 educational center for children ages 2-22 with Autism Spectrum Disorder — a neurological condition characterized by a wide range of symptoms that often include challenges with social skills, repetitive behavior, speech and communication.

In 2007, the CDC reported 1 in 150 children were diagnosed with autism. Now, 1 in 68 children get diagnosed.

Dunham views the school as one part of a growing societal recognition that, with the right support, people with autism can flourish.

She started the school with the Schuldt family, which has an autistic daughter named Sarah.

“We were two families that could not find the right environment for our children,” Dunham said. “Our kids needed to have more intensive therapeutic support. We wanted it to be an environment that was full of enrichment and resources: a safe environment for kids to learn.”

Individualized learning

Since its founding, the school has blossomed, with 51 students and 50 therapists and classroom teachers. With a 22,000-square-foot building and funding entirely from donations and student scholarships, the school is close to maxing out its space. Ten JSA students receive a Gardiner Scholarship from Step Up For Students, which publishes this blog. Meanwhile, 35 students receive McKay scholarships and six students pay out of pocket.

Dunham said Nick has excelled at the school. Within three months, he started reading.

“He has been able to be participative in his world, because he understands,” Dunham said. “He has been able to show us his intelligence in so many ways.”

The school focuses on helping children with autism and their families by channeling all available resources into supporting students, and by embracing what Dunham calls “outside-the-desk” thinking.

“Children are unique in their learning ability,” Dunham said. “We want to make sure that we leave no stone unturned as far as trying to reach them. If it requires a natural teaching environment, we do that. Whatever it takes to help them.”

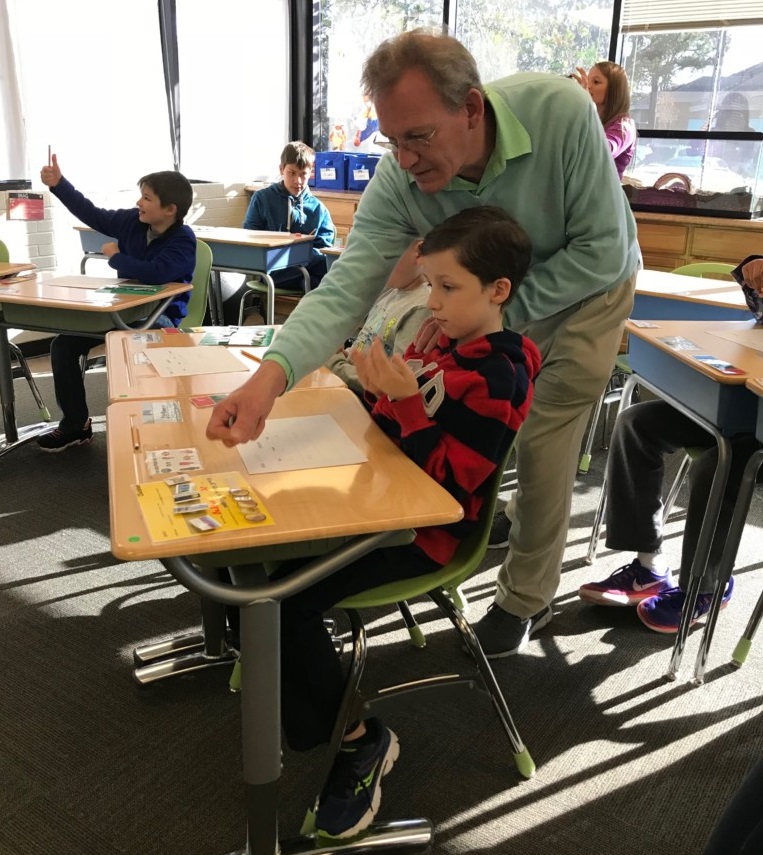

The school’s model blends highly structured classroom teaching environments and ABA clinical therapy. Applied Behavioral Analysis is a therapeutic approach that helps people with autism improve their communication, social and academic skills.

Chrystal Ramos, a clinical therapist at the school for the past two years, said lesson plans are tailored to students’ individual needs.

“When I was teaching at different schools that had lesson plans that we had to follow, it was not catered to each child,” she said. “A lot of students that were having trouble were falling through the cracks. We couldn’t focus on their needs. It was following the lesson plan.”

Trina Middleton, educational director at JSA, said many children have “splinter skills.”

They might master higher-level skills in a subject area without being able to demonstrate lower-level skills that educators typically view as building blocks.

For example, a student might be able to add or subtract numbers, but still struggle to match the number seven with a group of seven objects on the table – a concept known as 1:1 correspondence.

Many of the students work one-on-one with a teacher or therapist for half-day or all-day sessions. They also take part in an array of other activities such as music therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, yoga and karate.

Programs like music therapy are designed to cater to students’ interests, while also meeting their therapeutic needs.

“Many individuals with autism have an affinity for water and music,” Dunham said. “One of the things that we have been able to see with our music therapy program is that music for our students doesn’t just grab their attention. It has a healing property to it.”

Building social skills

During a recent visit to JSA, a teacher was dressed up as a painter to engage with students.

Krista Vetrano said she uses costumes to help introduce topics in a fun and creative way — a technique she calls “social modeling.”

Vetrano said she tries to make the characters relate to the topic of the lesson. Characters like Pablo Punctuation or Nanny Noun help teach grammar concepts. They give students the opportunity to ask questions practice getting to know someone different and new.

While the school embeds academics everywhere, the staff is focused on one long-term goal: helping students assimilate to the outside world.

For example, if a student has a fear of public restrooms, they visit the restrooms as a first step in helping the child to overcome his or her fear.

The school uses role-playing to help students understand how to greet people or handle situations like waiting in line.

“It is about making their world bigger and bigger,” Dunham said.

Ready for work

The school also implemented a vocational training program for older students to help them acquire skills to become gainfully employed in the future.

Dunham said she began the program because she wanted Nick to thrive as a citizen. Now she wants to expand the program to allow as many individuals as possible to gain skills.

“Our goal is not only train (students), but also to help them seek employment and retain employment,” Dunham said.

Dunham said at the end of the day the school will grow as needed to support the student base.

“We don’t want to grow at the expense of quality,” she said. “We want to make sure we don’t change the culture of learning we worked so hard to build for our students and their families.”

Nick takes part in vocational training at Publix.

His mother describes him as an anxious young man who has difficulty standing in one place. He craves order.

His job at the grocery store is to stack fruit on the shelves, which Dunham described as a perfect fit for him.

“When he goes into Publix and puts his apron on there is a calmness about him,” Middleton said. “He is actually participating and being expected to be responsible for a job that he enjoys and plays to his skill set. His pacing and anxiety decrease.”

Dunham said her son craves social interaction.

“He really loves to be around people,” she said. “That is one of the reasons he enjoys Publix.”

Life with autism

Kristopher Turcotte recently moved with his wife and son from South Carolina to Jacksonville. He was looking for options for his 8-year-old son, who has autism.

“This was one of the best options that we could find,” he said of JSA.

Since his son has enrolled in the school this summer he has acquired more speech.

“He has problems with social settings,” Turcotte said. “That is one of the things that the school has worked with him on.”

Dunham explained some students with autism also suffer from food allergies and sleep deprivation, or have a sensitivity to light and sound.

While all teens struggle with puberty, Dunham said for students with autism it is a “mountain to climb.”

She explained many teenagers with autism do not understand what is happening to their bodies. Some develop seizures.

“Puberty can bring out anxiety and aggression in our children,” she said. “We work with the children trying to obviously look for these indicators and what is happening in their life and try to support them first.”

Dunham worries as they grow up and leave school, they may not have all the support they essentially need.

“What is the next step for these students?” she said.

The statistics about increasing autism diagnoses only highlight the urgency for Dunham to develop a working community to support young adults with autism as they transition to adulthood.

“I am looking at a lifespan model that would provide the educational, vocational and residential support for our young adults,” she said.