Well-organized special interests vigorously oppose allowing publicly-funded education to occur outside the control of local school districts. If families have a desire for more options, the refrain often goes, districts can satisfy that demand with magnet schools.

Well-organized special interests vigorously oppose allowing publicly-funded education to occur outside the control of local school districts. If families have a desire for more options, the refrain often goes, districts can satisfy that demand with magnet schools.

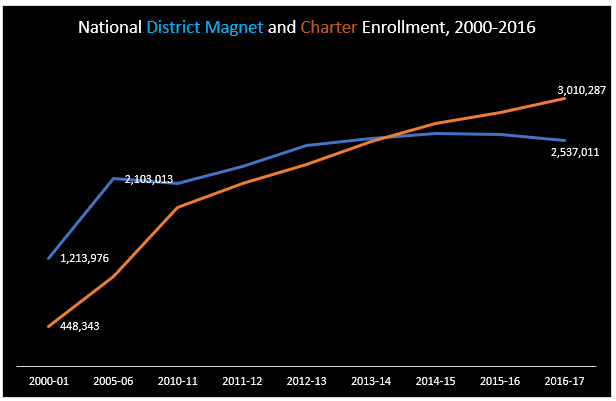

Magnet schools, utilized to lower racial segregation and typically featuring a specialized curriculum to attract enrollment without regard to attendance zones, got a running start on other forms of education choice. The first magnet debuted in 1965, while the first charter didn’t launch until the early 1990s.

At the turn of this century, unmet demand for school options found a release in the form of private choice and charter school programs. In 2000, these programs had not yet reached the ripe old age of 10 anywhere, and they were entirely absent in most states.

Nevertheless, the presence of choice options outside of districts seemed to spur the creation of additional magnet opportunities within districts; between 2000 and 2012, the number of magnet students more than doubled. Since then, however, magnet enrollment has plateaued. Why might that be the case?

If you work for a district school, your funding ultimately depends upon the number of students enrolled. Whether students attend charter schools, private schools, are homeschooled, use open enrollment to attend a different district school or move away, the result is fewer students in a particular district, and thus, less funding. Non-magnet district schools, thus, have an incumbent interest in minimizing choice-including of the magnet variety.

Incumbent interests may tolerate a certain amount of competition for students from district magnet schools if facing external pressure. External pressure can come from parents or schooling options outside the district, including other districts if they allow open enrollment. Incumbents ultimately have an incentive to keep magnet schools contained rather than allowing them to grow to meet parental demand.

Districts do not have the same ability to veto new charter schools, however, and shortly after the plateau in magnet enrollment in 2012, national charter enrollment exceeded that of magnet schools despite the 26-year magnet head start. The line-crossing seems all the more impressive considering the struggle that charters have in finding facilities.

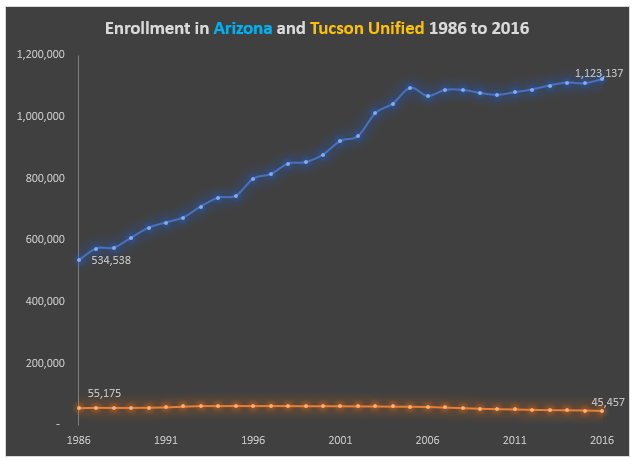

To clarify the political impediments, consider what very well may be the most impressive public school in Arizona: University High. This magnet school in the Tucson Unified School District serves a majority minority student body and ranked No. 15 nationally in U.S. News and World Report rankings. University High has a waitlist, while Tucson Unified has needs-enrollment and an abundance of vacant space caused by a combination of housing decisions, open enrollment, charters and overbuilding of school space during the pre-Great Recession boom.

Any rational actor might think that Tucson Unified would give it to the charter competition with both barrels by replicating University High repeatedly. Ooops … There we go again, bringing logic to a political fight.

Instead, University High is kept contained. Not only has Tucson Unified failed to replicate University High, it literally keeps it in the basement of another school. Meanwhile, adjacent districts continue to bring in students zoned for Tucson Unified, and charters keep growing their enrollments and waitlists. While a “protect the incumbents” mindset may seem to be rational in the short term, it serves districts poorly in the long term. In the late 1980s, more than 10 percent of Arizona students attended Tucson Unified schools. By 2016, that percentage had fallen to 4 percent.

Some districts, however, have been much more forward looking. One has been growing right in Tucson’s neighborhood. (More on that to come.)

The takeaway for now: Districts keep high-demand charters trapped in broom closets and basements for entirely predictable political reasons centering on incumbent political interests. You can buy a dog and have it sit on your lap and purr in an adorable fashion, but it’s not what you should expect to happen. Sadly, you shouldn’t expect districts to scale high-demand options in the current governance/incentive structures, either.